Abstract

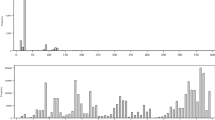

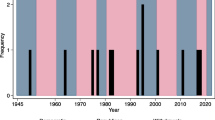

Do Social Democrats still expand the welfare state? This article argues that a time-constant policy-oriented expectation of Social Democratic behaviour neglects parties’ aspiration for other goals such as votes and offices, and therefore cannot explain why some Social Democratic parties have introduced welfare state retrenchment measures. Social Democrats can win votes and join coalitions by shifting rightwards. In contrast, they can pursue policy objectives by shifting leftwards. To communicate these shifts, in other words, ‘changes of heart’, parties send signals to voters and other parties before elections. This study analyses the effect of these party signals on the welfare state. Party manifesto data are used to compute the positive and negative signals parties send on welfare issues in their electoral manifestos. A pooled time-series analysis of 14 parliamentary democracies between 1972 and 2002 shows that Social Democrats enact retrenchment measures after having sent a negative signal on a welfare issue in election time, especially in the case of unemployment benefits. Most importantly, this study identifies when Social Democrats choose to retrench (part of) the welfare state, namely after having signalled ‘a change of heart’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Or suggest via case studies that more complex mechanisms explain the behaviour of Social Democrats vis-à-vis the welfare state (for example, Levy, 1999; Ross, 2000; Green-Pedersen, 2002).

For example, in a majoritarian electoral system, access to office and policy is only possible when a majority of the vote is obtained; however, in proportional representation systems this is not the case, which decreases the importance of votes (Müller and Strøm, 1999).

In some electoral systems, Social Democrats can also move to the left in order to win votes from smaller left-wing parties. However, by moving to the left, Social Democrats also pursue policy-seeking goals, and hence I subsume leftward movements under policy-seeking behaviour.

The last category mentioned in the description is about sexual and racial discrimination and has less to do with the welfare state. However, the MRG data set also has a separate issue for this category (per706: underprivileged minority groups). It seems likely that when racial and sexual discrimination was mentioned and was not explicitly connected to welfare programmes, it was coded under per706 rather than per503.

The party signals calculated for this article will be made available in a web appendix after publication.

In most cases, Social Democrats form a single-party government or are the senior partner in a coalition. Hence, the cabinet signal of a cabinet with Social Democrats is strongly correlated with the party signal of Social Democrats. In addition, using the Social Democratic party signal as a replacement for the entire cabinet signal does not give substantially different results. Substantively, it seems justified that the ambitions of one coalition party are toned down by the ambitions of its coalition partners. Therefore, the cabinet signal operationalization is preferred.

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Italy is omitted because of the complicated political situation in the larger part of the period under study, which hinders the calculation of meaningful cabinet signals per year.

One can also analyse the sum of these programmes. This is problematic, because each programme has its own political logic. For example, the odds of getting old are much higher than the odds of becoming unemployed or sick. This means that the pension system is relevant for a much larger group of people than the other two programmes.

Other programmes such as disability benefits or family programmes are important too, but they are not historically as important as the other categories. More problematically, there are no yearly replacement rate data available for these programmes.

The results of the analyses with family replacement rates are available on request.

An alternative to a country–year set-up is a country–cabinet set-up. However, to compare my findings with those in the literature, I adopt the literature's practice to use a country–year set-up.

Some of these cabinets had to be excluded, either because they were only short-lived or because there were missing data in one or more of the dependent variables.

Although a reduction in unemployment benefits was not initially part of the New Deal, Labour's employment strategy (Clasen, 2005), Scruggs (2006) reports a reduction in benefits in 2001.

Presenting all six models takes up too much space. However, they will be made available in a web appendix after publication.

References

Adams, J., Haupt, A.B. and Stoll, H. (2009) What moves parties? The role of public opinion and global economic conditions in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies 42 (5): 611–639.

Allan, J.P. and Scruggs, L. (2004) Political partisanship and welfare state reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science 48 (3): 496–512.

Beck, N. and Katz, J.N. (1995) What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review 89 (3): 634–647.

Bille, L. (1994) Political data yearbook: Denmark. European Journal of Political Research 26 (3/4): 279–287.

Boeri, T., Boersch-Supan, A. and Tabellini, G. (2001) Would you like to shrink the welfare state? A survey of European citizens. Economic Policy 16 (32): 9–50.

Boeri, T., Boersch-Supan, A. and Tabellini, G. (2002) Pensions reforms and the opinions of European citizens. The American Economic Review 92 (2): 396–401.

Brady, D., Beckfield, J. and Seeleib-Kaiser, M. (2005) Economic globalization and the welfare state in affluent democracies, 1975–2001. American Sociological Review 70 (4): 921–948.

Budge, I. and Farlie, D.J. (1983) Explaining and Predicting Elections. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Budge, I., Klingemann, H.D., Volkens, A., Bara, J. and Tanenbaum, E. (2001) Mapping Policy Preferences: Estimates for Parties, Electors and Government, 1945–1998. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Burgoon, N. (2006) Globalization is What Parties Make of It: Welfare and Protectionism in Party Platforms. GARNET Working Paper no. 3/6.

Castles, F.G. (1982) The Impact of Parties. Politics and Policies in Democratic Capitalist States. London: Sage.

Clasen, J. (2005) Reforming European Welfare States: Germany and the United Kingdom Compared. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clasen, J. and Siegel, N.A. (eds.) (2007) Investigating Welfare State Change: The ‘Dependent Variable Problem’ in Comparative Analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Downs, A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Ezrow, L., De Vries, C.E., Steenbergen, M. and Edwards, E.E. (2011) Mean voter representation versus partisan constituency representation: Do parties respond to the mean voter position or to their supporters? Party Politics 17 (3): 275–301.

Garrett, G. and Mitchell, D. (2001) Globalization, government spending and taxation in the OECD. European Journal of Political Research 39 (2): 145–177.

Green-Pedersen, C. (2002) The Politics of Justification: Party Competition and Welfare State Retrenchment in Denmark and the Netherlands from 1982 to 1998. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Ha, E. (2008) Globalization, veto players, and welfare spending. Comparative Political Studies 41 (6): 783–813.

Hicks, A. and Zorn, C. (2005) Economic globalization, the macro economy, and reversals of welfare: Expansion in affluent democracies, 1978–1994. International Organization 59 (3): 631–662.

Huber, E., Ragin, C. and Stephens, J.D. (1993) Social democracy, christian democracy, constitutional structure, and the welfare state. The American Journal of Sociology 99 (3): 711–749.

Huber, E. and Stephens, J.D. (2001) Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Iversen, T. and Cusack, T.R. (2000) The causes of welfare state expansion. Deindustrialization or globalization? World Politics 52 (3): 313–349.

Kitschelt, H. (2001) Partisan competition and welfare state retrenchment. When do politicians choose unpopular policies? In: P. Pierson (ed.) The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kittel, B. and Obinger, H. (2003) Political parties, institutions, and the dynamics of social expenditure in times of austerity. Journal of European Public Policy 10 (1): 20–45.

Klitgaard, M.B. (2007) Why are they doing it? Social democracy and market-oriented welfare state reforms. West European Politics 30 (1): 172–194.

Korpi, W. (1989) Power, politics, and state autonomy in the development of social citizenship: Social rights during sickness in eighteen OECD countries since 1930. American Sociological Review 54 (3): 309–328.

Korpi, W. and Palme, J. (2003) New politics and class politics in the context of austerity and globalization: Welfare state regress in 18 countries, 1975–1995. American Political Science Review 97 (3): 425–446.

Levy, J.D. (1999) Vice into virtue? Progressive politics and welfare reform in continental Europe. Politics and Society 27 (2): 239–274.

Müller, W.C. and Strøm, K. (1999) Policy, Office or Votes. How Political Parties in Europe make Hard Decisions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pierson, P. (1994) Dismantling the Welfare State: Reagan, Thatcher, and the Politics of Retrenchment in Britain and the United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pierson, P. (2001) The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Plümper, T., Troeger, V.E. and Manow, P. (2005) Panel data analysis in comparative politics: Linking method to theory. European Journal of Political Research 44 (2): 327–354.

Quinn, D.P. and Inclan, C. (1997) The origins of financial openness: A study of current and capital account liberalization. American Journal of Political Science 41 (3): 777–831.

Ross, F. (2000) ‘Beyond left and right’: The new partisan politics of welfare. Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 13 (2): 155–183.

Schumacher, G. (2011) When does the Left do the Right Thing? A Study of Party Position Change on Welfare Policies, Drei Laender Tagung Conference, Basel.

Schumacher, G., De Vries, C.E. and Vis, B. (2010) Why Political Parties Change their Position: Institutional Conditions and Environmental Incentives, MPSA General Conference, Chicago.

Schumacher, G. and Vis, B. (2010) To Retrench or not to Retrench: A Simulation of the Strategic Situation of Social Democratic Parties and the Emergence of Welfare State Retrenchment. VU Political Science Department. Working Paper Series no. 27.

Scruggs, L. (2006) The generosity of social insurance, 1971–2002. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 22 (3): 349–364.

Siaroff, A. (1999) Corporatism in 24 industrial democracies: Meaning and measurement. European Journal of Political Research 36 (1): 175–205.

Somer-Topcu, Z. (2009) Timely decisions: The effects of past national elections on party policy change. Journal of Politics 71 (1): 238–248.

Stimson, J.A. (1985) Regression in time and space: A statistical essay. American Journal of Political Science 29 (4): 914–947.

Swank, D. (2005) Globalisation, domestic politics, and welfare state retrenchment in capitalist democracies. Social Policy & Society 4 (2): 183–195.

Vis, B. (2010) Politics of Risk-Taking: Welfare State Reform in Advanced Democracies. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Vis, B. and Van Kersbergen, K. (2007) Why and how do political actors pursue risky reforms? Journal of Theoretical Politics 19 (2): 153–172.

Acknowledgements

This article has been presented at various occasions, including the workshop Comparative Analysis of Welfare Models and Welfare Workshop in Roskilde, October 2008 and the Politicologenetmaal in Nijmegen, May 2009. I thank all participants for their contributions, as well as Kees van Kersbergen, Barbara Vis and Paul Pennings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schumacher, G. Signalling a change of heart? How parties’ short-term ideological shifts explain welfare state reform. Acta Polit 46, 331–352 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2011.17

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2011.17