Abstract

This article examines the changing dynamics of electoral competition around an increasingly salient issue in Spanish politics: immigration. We argue that, although the issue is close to a ‘valence’ one in terms of the views of the electorate, the behaviour of the three main state-wide parties – analysed with data from party manifestos for the 1993–2011 period and of electoral campaign rhetoric between 2000 and 2011 – departs from the expectations of issue ownership competition. The result for the Spanish mainstream has therefore been a recurring ambivalence between adopting clear spatial positions on the issue and playing the competence card.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Radical right parties in Spain have only gained anecdotal political representation in local elections since 2003 (Llamazares and Ramiro, 2006). The radical right has, however, been more successful at the local and regional level, especially in Catalonia (Hernández Carr, 2011).

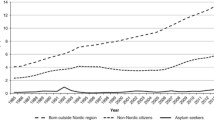

Asylum application statistics in Spain are very poor and the number of applications is not made public. Information is only available on those that have been processed administratively. In 1995 the total such ‘valid’ applications were 3294 and the highest number recorded in the period studied was in 2001 (9489 applications). As a result, the number of individuals with legally granted refugee status living in Spain has always been very low, and ranging between 8303 (in 1990) and 4661 (in 2009). More detailed statistics can be found in Morales et al (2012).

This massive drop in attention does not necessarily mean that cultural threat perceptions among the Spanish public have lost traction when the economy runs into trouble, as suggested by Bornschier (2010). Indeed, cultural threat perceptions increased gradually and continuously since the 1990s until 2006–2007. Unfortunately, all available time series are interrupted around 2007, but those that exist from the CIS immigration yearly surveys that started in 2007, slightly earlier than the economic crisis hit Spain, suggest that cultural threat perceptions either remained stable or continued to grow slightly after the crisis hit fully (surveys number 2731, 2773, 2817, 2846, 2918 available on www.cis.es/).

The expressions ‘immigrants’, ‘foreigners’ and ‘people from other nationalities’ are used interchangeably in surveys in Spain. The wording of the item in the ASEP surveys is: ‘What would you say about the number of people from a different nationality, race, religion or culture that come to live to our country? Do you think that they are too many, many, not many, or not too many?’ The wording of the CIS surveys is: ‘In your view, the number of immigrants currently in Spain is insufficient, acceptable, high, or excessive?’

Operationalised on a 1–7 scale until 2007, and on a 0–10 scale from 2008 onwards. On the 1–7 scale, extreme left positions are 1–2, centre-left positions are 3, centre positions are 4, centre-right positions are 5 and extreme right positions are 6–7. On the 0–10 scale, extreme left positions are 0–2, centre-left positions are 3–4, centre positions are 5, centre-right positions are 6–7 and extreme right positions are 8–10.

Except for the peaks in 2006–2007, the negative attitudes towards the level of immigration in Spain were not too different to those found in Britain, for example, in the late 1990s. 27.5 per cent of Spaniards thought that there were ‘too many’ immigrants in Spain as compared with 22 per cent of British who said they strongly agreed that ‘there are too many immigrants in Britain’ (Ipsos-Mori race relations and immigration trends). However, whereas in Britain the percentage of respondents holding this view oscillated between 30 and 40 per cent throughout the 2000s, in Spain it ranged between 40 and 65 per cent. In France, for example, the equivalent response oscillated between 20 and 30 per cent in the 2000s. Nevertheless, this heightened perception of an excessive number of immigrants has co-existed with a relatively positive evaluation of the effects of immigration on the economy. Survey data from the European Social Survey indicates that Spaniards have appreciated the benefits of immigration for the economy much more than the British, Dutch and French until the start of the crisis in 2008, when their views have converged (see on this Méndez et al, 2013).

The linear decrease of the PSOE’s competence reputations on immigration matches the generalised loss of faith in this party. Competence reputations of the PSOE managing issues like employment, education, the health system, the economy and terrorism also went down significantly. Between April 2006 and July 2011, the number of people who thought that the PSOE outperformed the PP in managing employment went down by 20 percentage points. This loss was also quite remarkable for the economy (17 per cent) and terrorism (15 per cent), and a bit less dramatic for traditionally Socialist-owned issues like education (11 per cent) and the health system (10 per cent). The PP’s issue competence reputation increased over the period analysed, even if it did not fully capitalise the PSOE’s decline. When looking at the difference between 2006 and 2011, the PP was perceived as particularly more competent to deal with employment and terrorism (10 per cent increase), and more competent to deal with the economy (7 per cent), education (6 per cent) and the health system (6 per cent).

See Morales and Ros (2012) for an analysis that includes the main nationalist–regionalist parties in the Basque Country, Canary Islands, Catalonia and Galicia.

The manual coding of manifestos proceeded in three steps. First, an exhaustive dictionary of keywords was used to help coders identify the parts of each manifesto that deal with immigration, to retrieve a corpus text of immigration-related statements that was then used for manual coding. The dictionary was produced in English, drawing on expert knowledge within the European Project SOM, and then translated into Spanish (see Appendix A). Second, natural sentences (our units of analysis) were coded, as there is evidence that dividing (some) sentences into quasi-sentences is not necessary to produce valid position estimates (Däubler et al, 2012).The codebook used for the manual coding included a number of variables that capture the position of immigration in a nuanced way. Of relevance to this paper is the positional question (‘What is the position toward the issue?’ – ranging from ‘−1=Strongly restrictive to migrants/conservative/pro-national residents/monocultural’ to ‘1=Strongly open to migrants/progressive/cosmopolitan/multi-cultural’). Examples were included to aid coding (see Appendix B). As a third step, in addition to coding the substantive positions on immigration, we calculated the number of words in all the sentences that constitute the shorter immigration-related corpus of the manifestos and computed their proportion in relation to the total number of words in each manifesto to create a proxy indicator of saliency of the immigration issue (see Table C1 in Appendix C). More information about the methodological approach is available in Ruedin and Morales (2012).

Party positions are the average value for each manifesto of all the individual position scores attributed to each natural sentence following the coding scheme described in Appendix B.

Our manifesto coding protocol allows us to examine the specific issue in relation to immigration that parties discuss in each sentence, as well as the ‘objects’ or social actors the statement refers to, and the way the statement is framed. See Ruedin and Morales (2012) for the full details on coding.

Formally, electoral campaigns in Spain only run during the 2 weeks before the elections. Informally, however, political parties are in electoral campaign mood much earlier than that. Although there is no set date that can be clearly considered as the starting date of the campaign, the nomination of candidates and the public issuing of the party manifesto typically happen within these 3 months.

In relation to this, our results show a sharp increase in the proportion of statements/claims made by political parties that are responding or criticising a political opponent: from 11 per cent in 2000 to 28 per cent in 2008.

For an analysis of the factors that might explain the absence of a relevant state-wide radical right party in Spain (see Llamazares and Ramiro, 2006).

The mean values for the variable on position for the parties’ public statements are provided in Table D1 in Appendix D.

References

Adams, J., Clark, M., Ezrow, L. and Glasgow, G. (2006) Are niche parties fundamentally different from mainstream parties? The causes and the electoral consequences of Western European parties’ policy shifts, 1976–1998. American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 513–529.

Bale, T. (2008) Turning round the telescope: Centre-right parties and immigration and integration policy in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy 15 (3): 315–330.

Bale, T., Green-Pedersen, C., Krouwel, A., Luther, K.R. and Sitter, N. (2010) If you can’t beat them, join them? Explaining social democratic responses to the challenge from the populist radical right in Western Europe. Political Studies 58 (3): 410–426.

Bélanger, É. and Meguid, B.M. (2008) Issue salience, issue ownership, and issue-based vote choice. Electoral Studies 27 (3): 477–491.

Berkhout, J. and Sudulich, M.L. (2011) Codebook for Political Claims Analysis. SOM Working Papers. Neuchâtel, Switzerland: University of Neuchâtel.

Boomgaarden, H.G. and Vliegenthart, R. (2009) How news content influences anti-immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. European Journal of Political Research 48 (4): 516–542.

Bornschier, S. (2010) The new cultural divide and the two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics 33 (3): 419–444.

Brighton, P. and Foy, D. (2007) News Values. London: Sage Publications.

Budge, I. and Farlie, D.J. (1983) Explaining and Predicting Elections: Issue Effects and Party Strategies in Twenty-Three Democracies. London: Allen & Unwin.

Cebolla, H. and González, A. (2008) La inmigración en España (2000–2007). De la gestión de los flujos a la integración de los inmigrantes. Madrid, Spain: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.

Däubler, T., Benoit, K., Mikhaylov, S. and Laver, M. (2012) Natural sentences as valid units for coded political texts. British Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 937–951.

Downs, A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Bros.

Enelow, J.M. and Hinich, M.J. (1984) The Spatial Theory of Voting: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Green-Pedersen, C. (2007) The growing importance of issue competition: The changing nature of party competition in Western Europe. Political Studies 55 (3): 607–628.

Hernández Carr, A. (2011) ¿La hora del populismo? elementos para comprender el ‘éxito’ electoral de Plataforma per Catalunya. Revista de Estudios Políticos 153: 47–74.

Jennings, W. (2009) The public thermostat, political responsiveness and error-correction: Border control and asylum in Britain, 1994–2007. British Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 847–870.

Koopmans, R., Statham, P., Giugni, M.G. and Passy, F. (2005) Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S. and Frey, T. (2006) Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research 45 (6): 921–956.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S. and Frey, T. (2008) West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Llamazares, I. and Ramiro, L. (2006) Les espaces politiques restreints de la droite radicale espagnole. Une analyse des facteurs politiques de la faiblesse de la nouvelle droite en Espagne. Pôle Sud-Revue de Science Politique 25: 137–152.

Meguid, B.M. (2005) Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review 99 (3): 347–359.

Méndez, M., Cebolla, H. and Pinyol, G. (2013) ¿Han cambiado las percepciones sobre la inmigración en España? Zoom Político. Madrid, Spain: Fundación Alternativas.

Morales, L. and Ros, V. (2012) La politización de la inmigración en España en perspectiva comparada. Barcelona, Spain: CIDOB.

Morales, L. et al (2012) Comparative data set of immigration-related statistics 1995–2009, support and opposition to migration project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Dataverse Network, http://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/17963 UNF:5:39JofJ7Hvg7NLQ8baogmhQ==V2 [Version].

Moreno, F.J. (2004) The Evolution of Immigration Policies in Spain: Between External Constraints and Domestic Demand for Unskilled Labour. Madrid, Spain: Instituto Juan March.

Odmalm, P. and Bale, T. (2014) Immigration into the mainstream: Conflicting ideological streams, strategic reasoning and party competition. Acta Politica, doi: 10.1057/ap.2014.28.

Petrocik, J.R. (1996) Issue ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850.

Rucht, D. and Neidhardt, F. (1999) Methodological issues in collecting protest event data: Units of analysis, sources and sampling, coding problems. In: D. Rucht, R. Koopmans and F. Neidhardt (eds.) Acts of Dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 65–89.

Ruedin, D. and Morales, L. (2012) Obtaining party positions on immigration from party manifestos. Paper presented at the Elections, Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) conference, Oxford.

van der Brug, W. and van Spanje, J. (2009) Immigration, Europe and the ‘new’ cultural cleavage. European Journal of Political Research 48 (2): 308–334.

van Spanje, J. (2010) Contagious parties. Party Politics 16 (5): 563–586.

van Spanje, J. (2011) Keeping the rascals in: Anti‐political‐establishment parties and their cost of governing in established democracies. European Journal of Political Research 50 (5): 609–635.

Walgrave, S. and Nuytemans, M. (2009) Party manifesto change: Friction or smooth adaptation? A comparative analysis in 25 countries (1945–1998). American Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 190–206.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results was carried out as part of the project SOM (Support and Opposition to Migration). The project received funding from the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 225522.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

Dictionary of keywords with Spanish translation used within brackets

Appendix B

Coding scheme used for the position variable employed in the coding of manifestos and electoral statements reported in newspapers.

Position

−1 ‘Strongly restrictive to migrants/conservative/pro-national residents/monocultural’

−0.5 ‘Somewhat restrictive to migrants/conservative/pro-national residents/monocultural’

0 ‘Neutral/ambivalent/technocratic/pragmatic’

0.5 ‘Somewhat open to migrants/progressive/cosmopolitan/multi-cultural’

1 ‘Strongly open to migrants/progressive/cosmopolitan/multi-cultural’

9 ‘Unclassifiable’

Appendix C

Appendix D

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morales, L., Pardos-Prado, S. & Ros, V. Issue emergence and the dynamics of electoral competition around immigration in Spain. Acta Polit 50, 461–485 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.33

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.33