Abstract

Tackling anti-social behaviour (ASB) was given central place in the 2004–2008 Home Office Strategic Plan, Tony Blair describing his government's policy agenda as a cultural ‘crusade’. Scholarly attention has often focused upon the implementation of the ASB management agenda but rather less attention has been given to the fast-moving politics behind the developing ASB debate. Following an introductory discussion connecting the ‘narrow politics’ of ASB strategy to a wider analysis of social divisions and the state of cultural politics in contemporary Britain, the article proceeds to consider ‘four phases’ embracing key changes, developments and turning points in the politics of ASB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prioritising the Politics of Anti-Social Behaviour

In many ways, the politics surrounding anti-social behaviour (ASB) raises as many novel and interesting issues as the more substantive questions raised for law, social policy, criminology, youthwork, crime prevention and community safety practice by ASB management and the, now notorious, anti-social behaviour order (ASBO) itself. The interaction between what we might call a ‘narrow’ politics of ASB, residing largely within formal political institutions and captured in the pronouncements of politicians, the documentation of the political process (White Papers, legislation, official guidance and processes of political scrutiny) and what has been called the broader ‘cultural politics’ of ASB (Squires, 2008) (press and public complaints and reactions, popular fears orchestrated through symbols of demonisation — ‘hooded yobs’ and ‘neighbours from hell’) is a vitally important part of the story.

However, largely absent from this story, especially in its earlier stages, markedly so from the perspective of a government formally committed to an ‘evidence-led’ policy agenda, is much in the way of academic or research-informed vindication of the ASB agenda. Also notably absent is any significant endorsement of a heavily enforcement-led approach to ASB management emerging from the crime prevention and community safety practitioner communities (such as the National Association for Youth Justice or the National Community Safety Network) developing in local government circles (Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnerships (CDRP)) in the wake of the 1997 Crime and Disorder Act. At best, the message emerging seems to be that (see Mayfield and Mills, 2008) enforcement must remain one of the options or, alternatively, enforcement opportunities must be a ‘last resort’ (House of Commons, 2005).

A number of closely related themes stand out in the politics of ASB in the UK. These include: important shifts in how the ‘politics of social order’ is configured and constructed; the change from a politics of material conditions, opportunities and social inclusion to a preoccupation with the ASB of individuals; related changes in the way social problems are explained and understood; and finally, there now appears a substantially increased willingness to deploy the apparatus of criminalisation to deal with social problems. One commentator has even noted that ASB management policies have seen the ‘reduction of public policy to pest control’ (Davies, 2006). Having briefly considered these issues, I will proceed to discuss the politics of ASB in Britain in four, more or less chronological phases.

The particular form taken by the attempt to regulate ASB or, perhaps, the means by which authorities have sought to extend processes of governance to ASB has attracted a certain amount of commentary from lawyers, primarily by virtue of the hybrid civil/criminal nature of the powers established, and by criminologists. However, despite the bespoke combined public/private character of the regulation entailed, there has been surprisingly little commentary from political scientists. It has rather fallen to the new (criminological) theorists of governance (e.g., Crawford, 2002; Stenson and Edwards, 2003; Hughes, 2007) to develop this discussion. Perhaps the rather lowly politics of public and social administration, the regulation of public nuisances and social housing management are not the place to look for ‘political science’. One suspects Foucault would have been amused because, he argued, it was precisely in the lowly minutiae of 19th century prison administration (timetables, regulations, classifications, records and observations) that, ‘the man of modern humanism was born’ (Foucault, 1977). Perhaps the ‘disaffected youth’ of 21st century disciplinary societ(ies) is similarly fabricated in police performance targets, Home Office press releases, crime prevention panel agendas, youth inclusion projects, naming and shaming procedures and the grainy digitised CCTV footage of contemporary societies.

Culture, Change and the Analysis of Social Problems

A first important issue provides us with a number of the elements for understanding the context in which concerns about ASB have arisen and the form they have taken. It requires some grasp on the wider cultural politics of public policy development. An insightful comment by David Garland, concluding his important first chapter overview of key changes in Anglo-American politics and society in The Culture of Control (2000) provides a useful starting point. Garland wrote: ‘Criminal justice strategies and criminological ideas are not adopted because they are known to solve problems’ (Garland, 2000, 26). Taking such a critical point seriously, given the rapid rise to prominence of a politics of ASB in the UK, requires that we look elsewhere for an understanding of its causes — and for its solution. We are not likely to find an explanation of the issue in the current oversupply of empirical detail about crime and disorder on our streets, in complaints about ‘yobs’ in ‘hoodies’ or in the widespread fear and concern about moral decline, de-civilisation and disrespect, or the behaviour of ‘others’.

Or rather, our understanding of the rise of ASB — as an idea — has to explore how these various ingredients have been put together. In effect, accepting that we cannot take the notion of ASB at face value, we need to know how the discourse itself has been constructed, what it means and what its significance might be. In a similar fashion, if policies to tackle ASB are not selected by virtue of their proven effectiveness (and this, as we have already noted, in a supposedly evidence-led, evaluation heavy, political climate) then we need to know the factors which are responsible for the current policy direction — or, which may be the same thing, the interests served by it. Garland's comment pushes us towards a more culturally situated and politically charged understanding of the ASB question and here there are some important and enduring cultural and political processes to address.

From the social to the anti-social?

Our late-modern encounter with incivility and ASB invites comparison with the emergence of ‘the social’ (Squires, 1990) as a sphere of political calculation and intervention in early modernity: sometimes referred to as the Social Question (Donzelot, 1979b; Hirst, 1981). There is an important parallel with Norbert Elias's conception of the civilising process (Elias, 1978, 1982); just as modernity began with the social question, late modernity appears plagued by its decivilising opposite. In turn, this transition from a preoccupation with the establishment and maintenance of ‘the social’ to a concern about the threat of the ‘anti-social’ has been reflected in important changes in our ways of understanding and explaining social problems as well as changes in our methods of dealing with them.

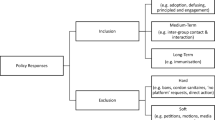

With modernity came the ‘social state’ or later, and more popularly, the ‘welfare state’ with its politics of social rights and citizenship (Marshall, 1963). The emergence of this discourse of ‘the social’ reflected the rise of certain methods of political calculation and regulation and certain ideological principles and traditions (especially principles of welfare and inclusion) in Western political culture. Yet welfare and inclusion were always a means to an end comprising incentives and sanctions, sticks and carrots. For Donzelot (1979a) the very polyvalence and contradictions of the social exposed something of its ambiguity, revealing that the social was neither an entity, outcome, or standard of benevolence but, rather, was best understood as a kind of political rationality, a discourse through which governance was rationalised and order maintained.

Anti-social policies

The discourse of ‘the social’ provided a kind of ideological currency for vindicating social and political arrangements, policies and relationships. In fact, just as commentators have detected important ‘decivilising’ features within Elias's wider civilising process (on the one hand the consolidation of the means of violence, on the other the ‘rediscovery’ of ‘interpersonal’ violence: Fletcher, 1997; Squires, 2000, 29), many commentators recognised a duality in the social. For example: Titmuss's own chilling observation that social welfare ‘could serve different masters’ (Titmuss, 1964); Foucault's detailed analysis of the inhumanity of much ‘prison reform’ (1977); Stedman-Jones' (1976) discussion of the exploitative evacuation of pauper children from London in the late 19th and early 20th century and finally E.P. Thompson's various discussions of unjust (punitive and coercive) class-based law-making associated with the onset of modern industrial society (1963, 1975). There are, doubtless, many more contemporary examples (Squires, 1990). Such observations also serve to remind us that the discourse of the social has always been profoundly nomadic and capable of migrating from democracy to corporation and culture at large in ways that Marcuse described in 1964. In other words, social interventions, practices and relationships can be profoundly uneven and ‘anti-social’ in their consequences.

From another perspective, however, neo-liberals such as Hayek or Nozick also showed little regard for ‘the social’, seeing it as little more than a contaminating discourse, watering down more established concepts of ‘justice’ or ‘freedom’. From here, of course it is but a short step to the ‘no such thing as society’ remark famously uttered by Mrs Thatcher. Subsequent commentators have noted, perhaps mischievously, that people believing there was ‘no such thing as society’, and acting accordingly (no limits to my excess, no interests than my own — in effect Neil Kinnock's depiction of the ‘me first’ society) might provide part of an explanation for our current preoccupation with ASB. Hedonistic excess, a politics of envy, under socialised exclusion and NIMBY-like intolerance represent, perhaps, different facets of the same phenomenon (Waiton, 2008), and part of the same cultural politics.

Anti-social conditions or anti-social people?

In fact, in a more profound sense, these disputes about the duality of the social have a direct relationship to explanation in social science. This has a direct bearing upon our contemporary politics of ASB. From Havelock Ellis to Barbara Wootton and well beyond, scholars have sought to account for deviant and ‘delinquent’ — or anti-social — behaviour. A tension, rooted in debates about structure and agency (or individual and society), has arisen regarding whether the adjective ‘anti-social’ is best applied to the circumstances and contexts in which certain forms of behaviour are produced and perpetuated; the offending behaviour itself; or to the perpetrators of the behaviour. Here we can perhaps go one better than Mr Blair: are we to be tough on the causes of crime, tough on crimeor tough on the criminals? Havelock Ellis expressed the general point in 1895, attributing criminality to man's social circumstances, instincts and relationships rather than any contrarily ‘anti-social’ ones (Ellis, 1895).

Likewise in the 1930s, Sir Alexander Paterson, architect of the reformed Borstal system spoke of the conditions in which Borstal inmates tended to grow up, referring to households in which ‘habits of honesty are with most difficulty taught’ (Ruck, 1951, 30). Paterson's idea approaches Elias's concept of ‘habitus’ — the contexts in which we grow and develop. The point was simply that anti-social conditions or environments provided at least part of an explanation for ‘delinquent’ or ASB. This appears to be something that more contemporary commentators have tended to overlook: ASB may be a fairly predictable outcome of anti-social circumstances, or a ‘normal’ response to exceptional circumstances.

Recently the media has latched onto a debate about the audio devices which emit an irritating, mosquito-like high-pitched whine inaudible to the over-25s. The devices are, apparently, to be fitted, in suitable vandal-proof casings, in places frequented by gatherings of young people in order to drive them away — somewhat like shooing away vermin (public policy as pest control). This is a strange kind of social inclusion. One suspects that society would be horrified if entertainment venues were to introduce steep steps to keep out the disabled or if the proprietors of cake shops introduced narrow doorways to deter fat people. Or, perhaps even more worryingly, people would not object. Maybe this would be a litmus test for how far we have come: standards are set, the responsibility for meeting them begins and ends with the individual, failure brings personal consequences.

There is some recognition of the importance of wider social contexts in Hermann Mannheim's (1946) discussion of the contribution of criminal justice to the politics of reconstruction. Mannheim saw ASB as a series of harms perpetrated against the community and contrary to the post-war spirit of optimism, progress and social cohesion. He specifically referred to ‘profiteering’ entrepreneurs and the non-payment (evasion) of taxes, not simply the breach of criminal laws. The idea here stands comparison with communist conceptions of malingering workers: parasites and enemies of ‘the people’. Mainstream criminology (among other perspectives) clearly rejected Mannheim's more expansive agenda but now it appears to be making a more selective return. Compared with contemporary conceptions of ASB, however, Mannheim's perspective raises two key issues. First, at times of perceived rapid social change (post-war Britain and today's late modernity) it may be necessary to assert the values of community and social inclusion more forcefully. Here, perhaps, is a key to Tony Blair's championing of the issue. However, secondly, for Mannheim, ASB was certainly not the sole preserve of the poorest or the young.

Governing through anti-social criminalisation?

We are left with a clear sense that ‘the social’ is not a fixed point of reference; it has justified both inclusion and exclusion, welfare or punishment, equality or freedom, the state or the market. Conversely being ‘anti-social’ has no fixed and simple meaning either but reflects wider interests and priorities. At the moment it is closely wedded to the cause of disorder management as existing social and community institutions seem unable to bring cohesion (indeed are often fragmenting and weakening — becoming anti-social — themselves) while the image of unconditional social welfare is frequently depicted as a political liability. In the place of welfare we have witnessed a marked expansion of criminal justice-led interventions, a process referred to by many commentators as ‘governing through crime and disorder management’ (Simon, 2007) and the criminalisation of social policy (Squires, 2006).

This shift in governing rationality is also aided and abetted by the changes in explanation and understanding alluded to already. In the age of social welfare, the ‘casualties’ of social progress and to some extent even the perpetrators of crime were often seen as victims of social circumstances. Their problems, even their criminality was a product of their upbringing and their conditions. In the age of criminalisation this understanding of social causation has been both discredited and abandoned, in one telling instance, by none other than the former prime minister, self-confessed champion of the ASB agenda, himself. People, he argued, are no longer interested in ‘understanding the social causes of criminality… people have had enough of this part of the 1960s consensus’ (Blair, 2004). The shift in focus is also marked by a much greater preoccupation with individual offender cognition and motivation, and a more traditional and ‘neo-classical’ conception of criminality (including challengeable assumptions about the supposedly rational core to a great deal of offending, perceptions about the existence of ‘committed evil’ among us, and regarding the existence of an anti-social sub-class at the base of society) which, taken together with the policies to address these putative problems, have led some commentators to debate the notion that we may have entered a new culture of punitiveness (Matthews, 2005; Pratt et al., 2005).

Four Phases

Having established the above context from which the contemporary ASB agenda has emerged, the rest of this discussion will consider four, reasonably self-contained, phases to the politics of ASB management in the UK. These phases help us to organise the ASB story in a useful fashion, although it needs to be acknowledged that this story is still not complete. There may be further phases to come, although those adopted here offer some important structure to our understanding of the issue. The phases adopted are:

-

The Ante-natal politics of ASB

-

The Phoney war

-

Full Speed Ahead and Respect

-

Rethinking and Turning down the heat

Phase 1: the ante-natal politics of ASB (Box 1)

There are a number of important dimensions to what we might call the ante-natal politics of ASB — before the birth of the modern concept of ASB and its associated discourses and certainly well before the New Labour's flagship Crime and Disorder Act introduced the ASBO in 1998. Elsewhere, these dimensions of the issue have been referred to as part of the ‘secret history’ of ASB (Squires and Stephen, 2005), although perhaps overlooked, neglected or forgotten might prove the more appropriate adjectives.

The ASB issue surfaced in the UK in a very particular way and was, from the start, closely linked to Tony Blair's own domestic political agenda: ‘For me this has always been something of a personal crusade’ (Blair, 2004). He came close to claiming authorship of the issue in the British context; ‘I wrote a piece about it in The Times in April 1988, the first time I remember using the phrase “anti-social behaviour”’. As Seldon notes (2007, 416), he retained a particular commitment to the issue even to the end of his premiership, ASB, after all, was a Blair, rather than a Brown issue. The political framing of ASB reflected a traditional social democratic ‘rights and duties’ formulation or, as the title of the 2003 White Paper put it, Respect and Responsibility (Home Office, 2003a) which owed much to Blair's moral philosophy informed by Tawney and John MacMurray.

The notion of reciprocity at the heart of this contractual conception of governance carries assumptions that echo debates from an earlier politics. In a context of widespread material deprivation, social and behavioural problems might largely be explained by structural factors. In an age of widespread affluence populated by dominant assumptions about abundant welfare support, the explanation for behavioural problems switches back to the more individual causes of failure or weakness. Such an interpretation is reflected in Mr Blair's (2004) references to both serious, organised and purposeful offenders and a chaotic and immoral, desperate and violent, underclass. Neither group's growth and development is adequately explained and criminal justice policies alone are posited as the appropriate response. Setting aside the (not unrelated) growth in ‘organised’ crime, many factors (not to mention many social policies) have combined to cultivate the development of an anti-social urban environment. Income inequality is a key, compounded by the concentration of disadvantage in residualised social housing estates (Flint, 2002; Burney, 2005) which have been the unfortunate recipients of a marked redistribution of criminal victimisation since the mid-1980s (Hope, 2001). The collapse (in particular) of youth labour markets and a marked racialisation of inequalities in opportunity have coincided with a growth in crimogenic opportunities associated with drugs, the supply of contraband and stolen goods, and a burgeoning night-time economy. In such contexts, as Paterson might have put it, habits of industry, responsibility and sobriety are not easily sustained.

In this context it was not surprising that the ASB issue first surfaced in the UK as a problem arising from the social housing management responsibilities of local authorities and social landlords. Section 222 of the 1972 Local Government Act had conferred on the reorganised local authorities a power to seek injunctions to control public nuisances. To a large extent this provision merely confirmed a longstanding practice of resorting to common law to terminate nuisances affecting the ‘quiet enjoyment’ of private property. This power establishes the broad basis from which more contemporary ASB management powers have evolved. As Burney has noted (2006), however, while older enforcement action by local authorities and the police certainly included ‘offensive behaviour’ by individuals (begging, soliciting, urinating in public, obscene display) in the nuisance category, the more modern conception, incorporated into the local authority brief in the 1970s, envisaged a more environmental conception of ‘nuisance’. This was to change following the combination of a more subjective and victim-centered politics with the public order concerns of the 1980s.

While freedom from threats and intimidation, like ‘quiet enjoyment’ of one's private life, had been a longstanding principle of English Law, the reference in the 1986 Public Order Act to words or behaviour likely to cause ‘harassment, alarm or distress’ effected an important shift in the criminalisation of nuisance. The words and behaviour of individuals were now firmly back on the nuisance agenda, and the offensiveness of this behaviour was relatively construed — in terms of its perception — or how it was likely to be perceived (vicarious offensiveness) by those subjected to it. As Burney describes, the phrase ‘harassment, alarm or distress’ found useful application in a number of areas having ‘an influential legislative life and eventually [becoming] a justification for some of New Labour's most repressive policies’ (Burney, 2006, 201). By this time, however, considerations of offensiveness had become reconnected with aspirations about the quiet enjoyment of one's property in the developing field of social housing management. The 1990 Environmental Protection Act had empowered local authorities to deal with residential noise complaints, noise abatement notices might be issued and failure to comply with these was a criminal offence — thereby anticipating the shift from civil law to criminal law that has been a feature of ASBO due process.

As the residualisation (and concentration of disadvantage) in social housing became more evident and its supply ever more scarce, social housing agencies, following the 1985 Housing Act, began to respond with more stringent enforcement of tenancy conditions (Burney, 1999). Conservative proposals for conditional ‘probationary’ or ‘introductory’ tenancies in social housing eventually culminated in the stronger enforcement powers contained in the 1996 Housing Act while Labour, in 1995 and still in opposition, expanded and developed the notion of ASB, planting this firmly at the heart of the Party's response (A Quiet Life) to community crime and disorder management (Labour Party, 1995).

Since the early 1990s, the field of crime and disorder has been a particularly fast-moving current, the politics of ASB especially so. The ASB agenda has also been subject to a marked degree of ‘mission-drift’. While the ASB issue was quickly developing within the housing management arena, the 1990s also witnessed the rapid growth of a related area of concern. The murder of James Bulger, in 1993, had marked a significant turning point, forcing a remarkable U-turn in public policy and galvanising a growing fear and mistrust of ‘disaffected’ even supposedly ‘feral’ youth (Brown, 1998).

Ironically, this was not unlike the way in which the individualised concept of ASB had first entered criminological discourse and come to influence debates about juvenile delinquency in the 1950s and 1960s. Anti-social personality disorder (ASPD), first identified in the USA in the 1940s (Glueck and Glueck, 1950; Hathaway and Monaschesi, 1953) was a psychological disorder often thought strongly predictive of future criminality (Eysenck, 1964). It was said to have an organic root in the psychological make-up of the individual and could be pronounced in adolescence. Although the central notion of ASPD itself made relatively little headway in the UK setting (Squires and Stephen, 2005, 51–67) it reaffirmed a number of issues that became crucial to the developing debate on youth crime and disorder: delinquency should be addressed at the level of the individual; ASB in youth was strongly predictive of future adult delinquency (the persistent young offender was especially problematic); early intervention was essential especially given the worrying indications that some young people were not ‘growing out of crime’ (Graham and Bowling, 1995).

Of course, the reason that this maturing out of crime was no longer occurring in the manner largely taken for granted a few years earlier (see Squires and Stephen (2005, 31–32) for the abrupt policy U-turn), concerned the social and environmental conditions in which young people were growing up and the opportunities (or lack of them), discrimination and inequality they faced (Pitts, 2003). In this sense, Britain's youth crime problem coincided with the so-called ‘broken windows’ discourse strongly influencing Anglo-American approaches to crime prevention and shaping the way that New Labour adopted the Left Realist crime control agenda. Tackling the problems of youth seemed to take second place to tackling the problems seen to be caused by youth (Goldson, 2000). As we have already seen, the locations where these issues were most forcefully played out were typically the sink estates and inner-city residential neighbourhoods where problems of inequality, discrimination, lack of opportunity and chronic patterns of victimisation were at their most acute. Above all these were the areas where young people and their behaviour soon became the focus of recurring neighborhood ASB complaints (Bottoms, 2006). And these were also the areas where, as discussed already, experience of nuisance/ASB enforcement action was, by virtue of the new legal powers, policy and developing practice in the housing management field, at its most developed.

The 1996 Audit Commission Report, Misspent Youth, which came to play a key role in New Labour's Youth Justice reforms, advocated managerialist and actuarial solutions (streamlining, fast-tracking, early intervention and inter-agency partnerships) for the problems of the contemporary youth justice system. Diversion and bifurcation strategies were introduced, depending upon the perceived seriousness or persistence of the offending behaviour of young people. As part of this ‘diversion’, ASBOs were designed to be quick and efficient in ‘nipping’ developing nuisance behaviour patterns ‘in the bud’. As Jack Straw, New Labour's first Home Secretary, said in the preface to No More Excuses, the White Paper introducing the Youth Justice Reforms, ‘we have to break the link between between juvenile crime and disorder and the serial burglar of the future’ (Home Office, 1987). In fact, as has been argued in a number of places (Brown, 2004; Squires and Stephen, 2005), drawing upon Cohen's ‘dispersal of discipline’ hypothesis (Cohen, 1985), what is often posed as ‘diversion’ especially in the context of a widespread moral panic about youthful crime and disorder, often turns into a simple process of delinquency ‘net-widening’. Precisely the same process has been observed in the housing management field, as Burney notes, drawing upon research by Hunter and Nixon (2001) and Brown (2004): the attribution of ‘multiple risk factors leads tenants to be labelled anti-social… housing management creates anti-social behaviour’ (Burney, 2005, 109).

Phase 2: the phoney war

Despite the rapid escalation of the war of words over ASB and the speed with which it, and especially the ASBO itself, had become adopted into the lexicon of concerns about the state of modern Britain — and in particular its young people — the next phase was, in some respects, something of an anti-climax. As Burney has noted (2002) the number of ASBOs issued by local authorities and CDRPs fell considerably below the government's expectations. Around 5,000 orders per year had been anticipated, but nearly 3 years after the implementation of the legislation orders granted totaled just over 500 (Burney, 2002, 469). In turn Home Secretaries Jack Straw and David Blunkett both urged local authorities to make greater use of their ASB management powers, including ASBOs. Subsequently, in 2004 ‘ASBO Ambassadors’ from well-performing areas, such as Manchester, were dispatched around the country to encourage the others to ‘up their game’ in the ASBO stakes (Squires, 2006).

While ASB policy may have seemed to falter at the level of implementation, a debate about the ASB was fast emerging even as popular conceptions of the issue were rapidly evolving and developing. In fact, the whole policy area of ASB has been marked, from the outset, by a combination of ‘mission drift’, expansionism and trespass. Often, what has emerged in support of the ASB policy has only emerged post facto, that is to say, explanations and justifications of new policy measures have only arisen following the introduction of the measures in question. In turn, however, each shift in policy and practice has been justified, by the managerial requirements of the original strategy. Thus, the public ‘naming and shaming’ of young people upon whom ASBOs had been imposed (in leaflets and posters distributed within their neighbourhoods and communities), contrary to the usual confidentiality applying to young people in trouble, has come to be justified on the grounds that an ASBO is not a criminal penalty but an order of the court. Furthermore, effective enforcement of orders, it was claimed, would be severely hampered if no-one knew which young people had been made subject to them.

The very first shift in the ASBO rationale was one of the most significant. The original Home Office draft guidance on ASBOs, produced in 1998, suggested that orders were not intended for young people aged under 16. This position had been stated in the House of Commons by Alun Michael, Home Office spokesman. He had remarked that the use of ASBOs against young people hanging about causing a nuisance and committing relatively minor offences such as criminal damage was ‘unlikely’ to be appropriate. Lobbying by a number of local authorities led the government to change its position, rewrite the guidance and, as a result, begin to cement the notion of ASB ever more firmly to the idea of youth. In Scotland, by contrast, partly by virtue of the fact that the more welfare-oriented Children's Hearings system has prevailed and no ASBO can be awarded unless via such a hearing, very few ASBOs have been awarded in respect of young people. In fact, until 2004 only those aged 16 plus could be subjected to an ASBO in Scotland (Pawson, 2007). By contrast, by the end of 2005, over 40% of ASBOs in England and Wales had been issued in respect of persons aged under 18.

Firming up behind the youth and ASB connection were a number of further issues. Evidential support for the targeting of ASB enforcement measures upon young people emerged in a Home Office Review of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders in 2002. The report argued that young people ‘were often perceived as the cause of many anti-social behaviour problems’, and that they were able to indulge in this behaviour ‘in the full knowledge that there were few criminal sanctions that could touch them’ (Campbell, 2002, 2). In other words, the notion of ASB supposedly pin-pointed the existence of a supposed ‘enforcement deficit’, especially marked in relatively deprived (‘broken windows’) communities regarding troubling behaviour by young people (Bottoms, 2006).

A wider rationale underscoring the necessity for the ASB strategy, the ‘collectivisation of harm’ principle emerged with Frank Field's provocatively titled book, Neighbours from Hell (2003). Field argued, ‘the distinguishing mark of ASB is that each single instance does not by itself warrant a counter legal challenge. It is in its regularity that ASB wields its destructive force’ (Field, 2003, 45). For ASB this represents an essentially liberating principle, the usual criminal legal framework (i.e.: wrongful act + culpability = responsibility and the basis for criminal intervention) need not apply, for each single instance of the behaviour complained about need not be a crime. As Hansen et al. (2003) put it; the issue is the cumulative impact of anti-social activities. An important part of the problem lay with the failings of the criminal justice system, specifically its inability to address the mismatch between ‘the accumulating distress for victims and [the] non-accumulating impact for offenders’ (Hansen et al., 2003, 82). This blind spot for the criminal justice system formed a second feature of the enforcement deficit, referred to earlier.

Such an acknowledgement of the consequences of persistent ASB, substantiating the case for the new ASB measures, fundamentally reinvented the whole jurisdiction of summary justice within a presumptive crime control paradigm. All of this emerged some 5 years after the first ASB measures had been introduced; ASB, therefore, served as a Trojan horse for the reform of the criminal justice system as a whole. Furthermore the ASB policy agenda was quickly followed by the more generic ‘justice gap’ initiative (Home Office, 2002). Tony Blair, acknowledged this much in his Criminal Justice Action Plan speech of 10th January 2006: ‘ASB law… came into being where general behaviour, not specific individual offences was criminalised. This has, bluntly reversed the burden of proof’ (Blair, 2006). The suggestion was beginning to form that the criminal justice system, and the Home Office itself, were ‘not fit for purpose’. In the same 2006 speech, Tony Blair commented on the fallacy of a criminal justice system ‘fighting 21st century crime with 19th century methods’, although many of the key elements of the more robust crime fighting alternative had already been slotted into place.

So here too, in Blair's wider stocktaking on the achievements of New Labour's criminal justice reform, there is a strong element of post hoc rationalisation. The 2006 speech virtually admits there was no overall coherent plan, New Labour were not so much leading, but rather following their own more particular criminalising tendencies, and it is only after nearly 10 years of government that the coherent rationale emerges with ASB a vital foundation stone in the reform of 21st century crime control.

The scale, organisation, nature of modern crime makes the traditional processes simply too cumbersome, too remote from reality to be effective… in a modern, culturally and socially diverse, globalised society and economy at the beginning of the 21st century [where] the old civic and family bonds have been loosened. Today I focus on ASB. Shortly we will do the same on serious and organised crime. But the principle is the same. To get on top of 21st century crime, we need to accept that what works in practice is a measure of summary power with right of appeal. Anything else is [just] theory (Blair, 2006).

The speech undoubtedly provided a comprehensive rationalisation of the measures that had preceded it and a bold agenda of reforms to come, taking a swipe, in passing, at the civil liberty and legal establishments still rooted in the ‘theoretical’ past and ‘hampering’ the necessary changes. Significantly, the speech also sought to vindicate some of the further license taken with the criminal justice system during this period.

For example, in keeping with the net-widening ‘dispersal of discipline’ approach referred to already, in 2002, sections 64–65 of the Police Reform Act allowed the courts to attach an ASBO to a criminal conviction and also established an ‘Interim ASBO’, which might be agreed by a court — on application from relevant authorities (police, local authorities, CDRPs, social landlords) — until such time as a proper court hearing for a full order could be held. The same year, the Home Office also published new guidance on non-statutory Acceptable Behaviour Contracts (ABCs) (voluntary agreements between young people, their families and the authorities spelling out behaviour that the named young person should specifically refrain from). ABCs had been first pioneered in Islington in 1999 to address nuisance behaviour by younger children (even aged under 10) or less serious and pre-criminal ASB (Bullock and Jones, 2004). While some commentators have seen ABCs as representing a potentially more democratic, ‘contractual’, and less intrusive or punitive form of intervention compared to an ASBO (Duff and Marshall, 2006), others have seen them as still further evidence of discipline dispersal and net-widening, their contractual aspect largely a façade and, by virtue of the potential threat of eviction (to which ABCs may be attached when families were living in social housing), no less punitive in their consequences (Stephen and Squires, 2004).

Phase 3: ‘asbomania’ and the ‘respect agenda’

Although phase 2 had seen, from the government's point of view, a disappointing response from local authorities in terms of the number of ASBOs they sought, the wider ‘politics of ASB’ had been changing fast. The government were pushing the issue forwards with Tony Blair championing the ‘RESPECT Agenda’.

In 2003, following a White Paper, Respect and Responsibility: Taking a Stand Against Anti-Social Behaviour (Home Office, 2003a), the Anti-Social Behaviour Act was introduced (implemented 2004). This extended and consolidated the range of enforcement powers in the government's ASB arsenal to include: closure notices, for disorderly or noisy premises or those in which drug dealing occurred; dispersal orders, to disperse and remove groups of young people (aged under 16) believed to be causing concern to members of the community; graffiti removal orders; parenting orders (for the parents of anti-social young people) and, perhaps most peculiarly of all, remedies for persons whose homes and gardens were overwhelmed by the high hedges of their inconsiderate neighbours. The implementation process was accompanied by a Home Office organised national ASB day-count (undertaken on 10th September 2003) when all CDRPs were required to submit details of all reports of ASB reported or recorded in their area within a given 24 hour period (Home Office, 2003b). In one sense the exercise represents a triumph of faith in the otherwise highly problematic arena of government criminal statistics. To make matters even more complex, as we have already noted the very definition of ASB contains ambiguities relating to the essentially relative judgments being reached regarding perceptions of ‘harassment, alarm and distress’. Even the Home Office Research and Statistics Directorate acknowledged that ‘the subjective nature of the concept makes it difficult to identify a single definition of ASB’ (Home Office: RSD, 2004). Nevertheless, the count produced a return of over 66,000 incidents (see Squires and Stephen, 2005, 35–39) apparently costing the country around £13.5 million each day. The incidents were further categorised, including such types as ‘nuisance’, ‘intimidation’, ‘harassment’, and ‘criminal damage’, but the single defining impression was not of a series of uniquely new ‘anti-social’ activities and behaviours for the vast majority were already criminal offences.

The expanding and amoeba-like logic of ASB enforcement had undergone another mutation, slipping into the background were the concerns about ‘nipping’ youth offending ‘in the bud’, or concerning the apparent ‘impunity’ of young people's offending. Equally less pressing, except in the sense that the government were lumping all these diverse behaviours together under the mantle of a single cause, ‘disrespect and irresponsibility’, was any argument about the ‘collectivisation’ or ‘accumulation’ of harm. Rather, the common denominator for ASB lay in the opportunity for streamlining the enforcement process — what, as we've seen, the prime minister came to refer to as the ‘modernisation’ of the criminal justice system.

We can spot these grander ambitions in the White Paper Respect and Responsibility itself, the government were seeking nothing less than ‘a cultural shift… to a society where we respect each other… a society where we have an understanding that the rights we all enjoy are based in turn on the respect and responsibilities we have to other people and to our community’ (Home Office, 2003a, 6). The point serves as a further reminder of the way in which ASB was firmly rooted in a cultural politics. It was an attempt to implement a model of active social democratic citizenship, where rights, as Tony Blair frequently reminded us, were closely tied to duties in a ‘something for something’ society. More than this, ASB had acquired something of a symbolic quality, it was important for what it signalled and specifically, as far as the government was concerned, it was interfering with the plausibility of a message about falling crime levels. As the White Paper puts it, ‘overall crime has dropped by over a quarter and some crimes, such as burglary and vehicle theft, by a third or more. Despite this many people perceive that levels of crime are high’ (ibid., 7). In other words, crime was falling but, because of the unsettling climate of ASB surrounding them, people either didn't realise or were disinclined to believe it.

In 2003, to accompany the new legislation the Home Office campaign, Together: Tackling Anti-Social Behaviour, was launched, while 2004 saw the first ‘ASBO Ambassadors’ dispatched around the country and the publication of the first Annual Report of the Together initiative (Home Office, 2004). The opening lines of the Annual Report echoed the government theme, ‘As crime has fallen, ASB has become a major cause of concern in communities across the country’. While the government were no doubt anxious not to let anything get in the way of the good news about crime, other commentators, notably Tonry (2004) have suggested that raising the spectre of ASB, and drawing people's attention to it amounted to a significant own goal, in effect, making a small problem much bigger. There are undoubtedly complex questions involved in evaluating public reactions to marginal shifts in crime rates and, as the ‘signal crimes’ perspective would have it (Innes, 2004), public reactions are more closely affected by how people feel about the threat of crime, and incidents in their own neighbourhoods and communities. In that sense, notwithstanding the fact that perceptions and symbolism were always central to the politics of ASB, the redistribution of crime, disorder and victimisation into poorer areas, as graphically described in Hope's work (Hope, 2001), meant that both crime and ASB were still unacceptably high in the most deprived areas. People's concerns had not shifted from crime to ASB, in any event, as the Day Count exercise had shown these were essentially the same problematic activities and behaviours. Rather, in those areas most affected by high levels of routine crime and disorder, the government was offering to upgrade its enforcement activity and target particular problems within a new ASB enforcement paradigm.

Further evidence of the significance of ASB interventions as a new enforcement process came with the emerging evidence of the pattern of ASBOs awarded after 2002 when the ASBO ‘on conviction’ (CrASBO) became available to the courts. As Burney (2008) has shown, despite the government's enthusiasm for increasing the take up of the free-standing ASBO as a ‘preventive’ measure, since 2003 the majority of orders awarded have accompanied a criminal conviction (Matthews et al., 2007) (Figure 1).

By 2005 a range of critical voices had begun to surface in response to the ASB and ‘Respect' policies. A series of organisations, including Liberty, the National Association of Probation Officers, the Children's Rights Alliance, the Community and Youth Workers’ Union, Mind and Inquest, came together to form ASBO Concern, which lobbied parliament in July 2005 regarding the policy and practice of ASB management. According to Shami Chakrabarti, Britain was in the grip of a bout of ‘asbomania’ (2006; Chakrabarti and Russell, 2008). The organisation was compiling a dossier on the most extreme or bizarre cases of ASBOs awarded (http://www.statewatch.org/asbo/ASBOwatch.html) and specific concerns were voiced about the breaches of rights entailed in ASBO proceedings; the use of ASBOs in the case of people (including children) with psychological and personality disorders; and the re-opening of a back-door route into prison for certain groups (such as street drinkers, beggars, and prostitutes who breached their orders) that parliament had otherwise intended to divert from imprisonment. Other critical voices within both community safety professional practice and academic research and evaluation also began to surface at this time. Around the same time, the rate at which ASBOs appeared to be breached also began to raise concerns. We will return to these issues in the final section.

Undeterred by the criticism that the ASB management policy was beginning to attract, in 2006 the government launched the Respect Action Plan (http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/documents/respect-action-plan) emphasising civic responsibility, community empowerment and cohesion to tackle the stubbornly resistant causes of ASB in families, classrooms and the community at large. The Action Plan also delivered additional funding to 40 so-called ‘Respect Zones’ designed, in the words of Louise Casey (the head of the ‘Respect Taskforce’ and dubbed the ‘Respect Tsar’ by the media) ‘to show how we can take the programme forward and point people in the right direction as well as keeping up the unrelenting drive to tackle anti-social behaviour… with parenting classes and family projects that tackle the really, really difficult people in our communities’ (Casey, quoted: 22 January 2007).

The Action Plan was nothing if not sweeping in its ambitions; critics argued that Casey's role seemed nothing less than a programme to reform ‘British manners’. There may indeed be some truth in this, after all, since 2004, the Strategy Unit in the Cabinet Office, accepting a connection between selfish values, criminality and intolerance (Halpern, 2001), had been exploring the extent to which public policy interventions could have a positive impact upon values, attitudes and behaviour (Halpern et al., 2004). In a sense the question poses the familiar old liberal dilemma about how far government can, or should, go in ‘making people good’ by law. On the positive side, the Action Plan document said relatively little about ASBOs and enforcement. Instead the document was populated by phrases seemingly lifted from an inspirational 12-step programme of personal renewal: ‘The only person who can start the cycle of respect is you’; ‘Give respect–Get respect’; and ‘Respect cannot be learned, purchased or acquired it can only be earned’. The assumption implicit in the slogans seemed to be that such ‘respect and disrespect’ issues, and the behaviour to which they were related, were constructed almost entirely as questions of choice and personal motivation. Social contexts and circumstances scarcely mattered, nor did they explain anything, this was all about individuals. And in any event, those who would not help themselves would feel the consequences.

Phase 4: rethinking and turning down the heat

Even as the ASB Act of 2003 was being first implemented, and a debate developing about the government's ASB strategy, new questions were beginning to emerge. In April 2004 Rhodri Morgan, chair of the Youth Justice Board (YJB), first expressed his concern regarding the way that ASBO breaches were adding to the already high numbers of children and young people in custody. Despite Article 37 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child insisting that custody should only be used for children as a matter of last resort, 81 children had been given custodial sentences following their breach of ASBOs between June 2000 and December 2002. In 2006 a National Audit Office report noted that, overall, up to 50% of ASBOs were being breached (National Audit Office, 2006).

In turn, the debate on ASBO breaches prompted a wider discussion of the effectiveness of ASB management strategies. In some reports, widely circulated in the media, ASBOs were being ‘reinterpreted’ by some of their recipients, becoming delinquent ‘badges of honour’ or ‘street diplomas’, according to the press. There was seldom much in the way of real research evidence to substantiate these claims, most of the published research with ‘ASBO subjects’ pointed to young people very much struggling to cope with the circumstances of their orders — and the potential consequences, which often compounded their sense of social exclusion (Matthews et al., 2007; Goldsmith, 2008; McIntosh, 2008). The YJB survey of young people on ASBOs found only a few who thought their orders were amusing or ‘cool’ (Solanki et al., 2006). Rather, as Wain (2007) has noted, those with ASBOs tended to feel themselves exposed to more intensive police surveillance, especially when subjected to public ‘naming and shaming’. The badge of honour myth is probably more attributable to the naivety of journalists confronted by stigmatised and excluded young people putting a brave face on their situation. How else might they be expected to respond? A defiant, self-destructive masculine bravado in the face of hopelessness: the only resource left?

As is clear in the forgoing discussion, by this stage in the ASBO story, the research and evaluation work, often missing earlier, had now begun to appear. Furthermore this work had now begun to engage with ASBO subjects themselves rather than simply the professionals, agencies and processes delivering the policy. Even here, however, differences of emphasis were becoming apparent. We have already noted the regional disparities in ASBO implementation, which the government had sought to address, yet there were other differences of emphasis. In particular, there appeared a growing recognition that a balance had to be maintained between enforcement action and the support necessary to ensure that ASBO subjects had a reasonable chance of complying with and therefore completing their orders satisfactorily (Millie et al., 2005; Solanki et al., 2006). In Wales, Edwards and Hughes (2008) have reported a more resilient commitment to an inclusive conception of community safety as opposed to an enforcement-centred approach. Likewise, McIntosh (2008) describes a ‘stepped’ approach towards the last resort of an ASBO in Cardiff. Even the London Borough of Camden, once regarded as London's ASBO capital, now claims a ‘six-stepped approach’ (even though an ASBO could be an option as early as step 3) alongside a commitment to more support and diversion work (Preest, 2007). Finally, in Scotland, as we have seen, the youth justice system, centred upon the Children's Hearings process, has ensured that the numbers of ASBOs imposed on young people has remained very low.

A more critical attitude, hitherto somewhat overlooked, regarding ASB enforcement, has begun to emerge from within the professional practitioner community. In January 2007 Rhodri Morgan resigned as head of the YJB, criticising politicians and journalists alike for demonising a generation of young people as ‘thugs’ and ‘yobs’ in their efforts to assert a tough approach to ASB. Morgan argued that not only was the policy wrong — putting extra unecessary pressure upon the youth justice system as a whole — it was also driven by counter-productive police performance indicators that encouraged the police to (in his telling and evocative phrase) ‘pick the low hanging fruit’ — the quickest and easiest way of meeting their performance targets — rather than concentrating on the crimes causing the greatest harm and concern in the community.

With the departure of Tony Blair from Downing Street, always the most committed enthusiast of the ASB strategy, some of the issues and concerns surfacing regarding the ASB policy began to have an impact in Whitehall. In July 2007, Ed Balls, the new Secretary of State in the Department of Children, Schools and Families, signaled a clear break with the Blairite line on ASB. In his speech he commented that, ‘I want to live in the kind of society that puts ASBOs behind us’. The remark was taken to indicate a new view in government that the number of ASBOs awarded was not the mark of a successful strategy but rather a mark of failure. Furthermore, the Respect Strategy was quickly folded up into a new Youth Task Force situated not in the Home Office but in the Department of Children, Schools and Families, and Louise Casey was moved to a new role in the Cabinet Office, chairing an inter-departmental review looking at how to improve the performance of frontline agencies engaging communities in the fight against crime.

Finally, the publication of the latest ASBO statistics by the Home Office has revealed that the number of ASBOs issued fell by 34% between 2005 and 2006 while the breach rate by young people increased from 47 to 61% in 2006. The new figures were greeted in the Guardian newspaper as heralding the ‘death throes’ of the ASBO (Travis, 2008), although the Home Secretary was keen to point out that a reduced number of ASBOs did not imply any lessening in the government's commitment to tackling ASB, but simply the fact that a greater variety of ‘early intervention’ measures (parenting orders, ABCs and support orders) were now available to practitioners working in CDRPs. How far the Home Office was acceding to the more cautious line on youth offending emerging from the Department of Children, Schools and Families may be unclear. Only one day earlier the aggressive rhetoric had been well to the fore as the Home Secretary urged police to ‘harrass’ and ‘hound’ ‘young thugs’, ‘to make their lives as uncomfortable as possible’ (Wintour, 2008). The Home Secretary was commenting on the falling ASBO figures and commending a police initiative in Essex whereby young offenders were filmed in targeted ‘name and shame’ initiatives, to give them ‘a taste of their own medicine’ (even though the practice may raise human rights issues). It is not inconceivable that the tough-talking was part of a political smokescreen to reassure voters about New Labour's law and order credentials after some bad local election results the week before. Here too, however, the ASB agenda conforms to type, as was noted at the very beginning of this article, the interaction between a ‘narrow’ politics of ASB, and a wider ‘cultural politics’ is a vitally important part of the story.

Conclusion: The End of the ASBO Era, or Just A New Phase?

How far the establishment of a Youth Taskforce and the associated announcements amount to a real cooling of the rhetoric on ASB — let alone the brakes being applied to the enforcement-led criminalisation strategy remains to be seen. Certainly, the CrASBO, ASBO, Penalty Notices for Disorder, ABCs, Dispersal Orders, Parenting Orders and the like are finding ready employment around the country. Yet it is scarcely credible to claim that now Britain has been well and truly moralised. In any event, a softening of the line on ASBOs is hardly the point, on this the revisionist community safety practitioner, critical criminologist and civil libertarian can surely come to agreement: it is not really about ASBOs. The real issue concerns the ways in which the discourse of ASB has fast-tracked, augmented and relativised the process of criminalisation: a process that the former prime minister tended to justify as the necessary ‘modernisation’ of the criminal justice system.

Here, it may be appropriate to give the last word to Richard Sennett. In his refreshingly challenging book on Respect, published in 2003, just as the government was pushing through the legislative programme arising from the Respect and Responsibility White Paper, he commented that policy-makers often have a poor grasp of psychology. ASB has, arguably, demonstrated precisely that. Excluding the excluded, licensing the intolerant, punishing children are strange outcomes indeed for a policy entitled: ‘Respect’ (Sennett, 2003).

References

ASBO Concern. See, The Guardian, 5 April 2005.

ASBO Watch: http://www.statewatch.org/asbo/ASBOwatch.html.

Blair, T. (2004) ‘Speech on the launch of the five-year strategy for crime’, 19 July 2004.

Blair, T. (2006) ‘Speech on the launch of the RESPECT Action Plan, 10 January.

Bottoms, A.E. (2006) ‘Incivilities, Offence and Social Order in Residential Communities’, in A. von Hirsch and A.P. Simester (eds.) Incivilities: Regulating Offensive Behaviour, Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Brown, A. (2004) ‘Anti-social behaviour, crime control and social control’, Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 43 (2): 203–211.

Brown, S. (1998) Understanding Youth and Crime, Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bullock, K. and Jones, B. (2004) ‘Acceptable behaviour contracts: addressing anti-social behaviour in the London Borough of Islington’, Home Office On-Line Report 02/04, Home Office, London.

Burney, E. (1999) Crime and Banishment: Nuisance and Exclusion in Social Housing, Winchester: Waterside Press.

Burney, E. (2002) ‘Talking tough, acting coy: what happened to the Anti-Social Behaviour Order?’, Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 41: 473–474.

Burney, E. (2005) Making People Behave: Anti-Social Behaviour, Politics and Policy: The Creation and Enforcement of Anti-social Behaviour Policy, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Burney, E. (2006) ‘“No spitting”: Regulation of Offensive Behaviour in England and Wales’, in A. von Hirsch and A.P. Simester (eds.) Incivilities: Regulating Offensive Behaviour, Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Burney, E. (2008) ‘The ASBO and the Shift to Punishment’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Campbell, S. (2002) ‘A review of anti-social behaviour orders’, Home Office Research Study No. 236. Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/hors236.pdf.

Chakrabarti, S. (2006) ‘Asbomania’, BIHR Lunchtime Lecture 10 January 2006, http://www.liberty-human-rights.org.uk/publications/3-articles-and-speeched/asbomania-bihr.PDF.

Chakrabarti, S. and Russell, J. (2008) ‘ASBO-mania’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Cohen, S. (1985) Visions of Social Control, Cambridge: Polity.

Crawford, A. (2002) ‘The Governance of Crime and Security in an Anxious Age: The Trans-European and the Local’, in A. Crawford (ed.) Crime and Insecurity: the Governance of Safety in Europe, Cullompton: Willan.

Davies, W. (2006) ‘Potlach weblog’, http://potlach.typepad.com 5 July 2006, cited in Harris, K. Respect in the Neighbourhood, Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing, p. xiii.

Donzelot, J. (1979a) ‘The poverty of political culture’, Ideology and Consciousness 5 (Spring): 73–86.

Donzelot, J. (1979b) The Policing of Families, London: Hutchinson.

Duff, R.A. and Marshall, S.E. (2006) ‘How Offensive Can You Get?’, in A. von Hirsch and A.P. Simester (eds.) Incivilities: Regulating Offensive Behaviour, Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Edwards, A. and Hughes, G. (2008) ‘Resilient Fabians? Anti-social Behaviour and Community Safety Work in Wales’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Elias, N. (1978) The Civilising Process: Volume 1 The History of Manners, Oxford: Blackwell.

Elias, N. (1982) State Formation and Civilisation, Oxford: Blackwell.

Ellis, H. (1895) The Criminal, 2nd edn, London: Walter Scott Publishers.

Eysenck, H.J. (1964) Crime and Personality, London: Routledge.

Field, F. (2003) Neighbours from Hell: The Politics of Behaviour, London: Politico's Publishing.

Fletcher, J. (1997) Violence and Civilisation, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Flint, J. (2002) ‘Social housing agencies and the governance of anti-social behaviour’, Housing Studies 17 (4): 619–637.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish, London: Allen Lane.

Garland, D. (2000) The Culture of Control, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldsmith, C. (2008) ‘Cameras, Cops and Contracts: What Anti-Social Behaviour Management Feels Like to Young People’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Goldson, B. (ed.) (2000) The New Youth Justice, Lyme Regis: Russell House.

Glueck, S. and Glueck, E.T. (1950) Unraveling Juvenile Delinquency, New York: Commonwealth Fund.

Graham, G. and Bowling, B. (1995) ‘Young people and crime’, Home Office Research Study 145, HMSO, London.

Halpern, D. (2001) ‘Moral values, social trust and inequality: can values explain crime?’, British Journal of Criminology 41 (2): 236–251.

Halpern, D. et al. (2004) Personal Responsibility and Changing Behaviour, Prime Minister's Strategy Unit paper. London: Cabinet Office.

Hansen, R., Bill, L. and Pease, K. (2003) ‘Nuisance Offenders: Scoping the Public Policy Problems’, in M. Tonry (ed.) Confronting Crime: Crime Control Policy Under New Labour, Cullompton, Willan Publishing.

Hathaway, S.R. and Monaschesi, E.D. (1953) Analysing and Predicting Juvenile Delinquency with the MMPI, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hirst, P. (1981) ‘The Genesis of “The Social”’, in Politics and Power 3, London: Routledge.

Home Office. (1987) ‘No More Excuses’, White Paper, Cm. 3809, HMSO, London.

Home Office. (1998) ‘Draft guidance document: anti-social behaviour orders’, paras 3.5, 3.10, Home Office, London.

Home Office. (2002) ‘Narrowing the justice gap’, http://www.cps.gov.uk/Publications/docs/justicegap.pdf.

Home Office. (2003a) Respect and Responsibility: Taking a Stand Against Anti-Social Behaviour, Home Office, London: http://www.archive2.officialdocuments.co.uk/document/cm57/5778/5778.pdf.

Home Office. (2003b) ‘One day count of anti-social behaviour’, http://www.respect.gov.uk/uploadedFiles/Members_site/Documents_and_images/About_ASB_general/OneDayCount2003_0068.pdf.

Home Office. (2004) Together, Tackling Anti-Social Behaviour: One Year On, London: Home Office.

Hope, T. (2001) ‘Crime Victimisation and Inequality in Risk Society’, in R. Matthews and J. Pitts (eds.) Crime, Disorder and Community Safety, London: Routledge.

House of Commons, Home Affairs Select Committee. (2005) ‘Anti-social behaviour’, Fifth Report of Session 2004–05, HC 80–1, The Stationery Office, London.

Hughes, G. (2007) The Politics of Crime and Community, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Hunter, C. and Nixon, J. (2001) ‘Taking the blame and losing the home: women and anti-social behaviour’, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 23 (4): 395–410.

Innes, M. (2004) ‘Signal crimes and signal disorders: notes on deviance as communicative action’, British Journal of Sociology 55 (3): 335–355.

Labour Party. (1995) A Quiet Life: Tough Action on Criminal Neighbours, London: The Labour Party.

Mannheim, H. (1946) Criminal Justice and Social Reconstruction, London: Routledge.

Marshall, T.H. (1963) ‘Citizenship and Social Class’, in T.H. Marshall (ed.) Sociology at the Crossroads, London: Heinemann.

Matthews, R. (2005) ‘The myth of punitiveness’, Theoretical Criminology 9 (2): 175–201.

Matthews, R., Easton, H., Briggs, D. and Pease, K. (2007) Assessing the Use and Impact of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Mayfield, G. and Mills, A. (2008) ‘Towards a Balanced and Practical Approach to Anti-Social Behaviour Management’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

McIntosh, B. (2008) ‘ASBO Youth: Rhetoric and Realities’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Millie, A., Jacobson, J., McDonald, E. and Hough, M. (2005) Anti-Social Behaviour Strategies: Finding a Balance. ICPR and Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Bristol: The Policy Press.

National Audit Office. (2006) ‘Tackling anti social behaviour’, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General, HC 99 Session 2006–2007, 7 December 2006, The Home Office, London.

Pawson, H. (2007) ‘Monitoring the use of ASBOs in Scotland’, DTZ Pieda Research & Heriot-Watt University, http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/198276/0053019.pdf.

Pitts, J. (2003) The New Politics of Youth Crime, Lyme Regis: Russell House.

Pratt, J., Brown, D., Hallsworth, S. and Brown, M. (eds.) (2005) The New Punitiveness: Trends, Theories, Perspectives, Cullompton: Willan.

Preest, T. (2007) ‘Finding the balance: service provision and ASBOs in the London borough of Camden’, Presentation to Day Conference ‘Examining the Use and Impact of ASBOs’. London Southbank University, 23 November.

Ruck, S.K. (ed.) (1951) Paterson on Prisons, London: F. Muller.

Seldon, A. (2007) Blair Unbound, London: Simon & Schuster.

Sennett, R. (2003) Respect: The Formation of Character in an Age of Inequality, London: Penguin/Allen Lane.

Simon, J. (2007) Governing Through Crime: How the War on Crime Transformed American Democracy and Created a Culture of Fear, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solanki, A.-R., Bateman, T., Boswell, G. and Hill, E. (2006) Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, London: Youth Justice Board.

Squires, P. (1990) Anti-Social Policy: Welfare, Ideology and the Disciplinary State, Hemel Hempstead: Harvester/Wheatsheaf.

Squires, P. (2000) Gun Culture or Gun Control: Firearms, Violence and Society, London: Routledge.

Squires, P. (2006) ‘New Labour and the politics of antisocial behaviour’, Critical Social Policy 26 (1): 144–168.

Squires, P. (2008) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Squires, P. and Stephen, D.E. (2005) Rougher Justice: Anti-Social Behaviour and Young People, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Stedman-Jones, G. (1976) Outcast, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Stenson, K. and Edwards, A. (2003) ‘Crime control and local governance: the struggle for sovereignty in advanced liberal polities’, Contemporary Politics 9 (2): 203–218.

Stephen, D.E. and Squires, P. (2004) Community Safety, Enforcement and Acceptable Behaviour Contracts, Brighton: HSPRC, University of Brighton.

Thompson, E.P. (1963) The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Thompson, E.P. (1975) Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act, London: Allen Lane.

Titmuss, R. (1964) ‘The limits of the welfare state’, New Left Review 27: 28–37.

Tonry, M. (2004) Punishment and Politics: Evidence and Emulation in English Crime Control Policy, Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Travis, A. (2008) ‘ASBOs in their death throes as number issued drops by a third’, The Guardian, 9 May.

Wain, N. (with E. Burney) (2007) The ASBO: Wrong Turning, Dead End, London: Howard League for Penal Reform Wain.

Waiton, S. (2008) ‘Asocial not Anti-social: The Respect Agenda and the “Therapeutic Me”’, in P. Squires (ed.) ASBO Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance, Bristol: The Policy Press.

Wintour, P. (2008) ‘Police should harass young thugs — Smith’, The Guardian, 8 May.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Squires, P. The Politics of Anti-Social Behaviour. Br Polit 3, 300–323 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2008.16

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2008.16