Abstract

David Cameron's advocacy of the ‘Big Society’ in the run-up to the 2010 general election was the culmination of his strategy, as Opposition Leader, to detoxify the Conservative brand, and persuade voters that the Party had moved on from Thatcherism. This article traces the genealogy of the concept, which echoes Edmund Burke as well as several senior figures from the party's more recent history. Despite Cameron's evident enthusiasm for the idea, much of the British public, as well as many Conservatives themselves, remain unimpressed. Indeed, some of them profess uncertainty about what exactly the ‘Big Society’ is: whereas others think they know what it is, and don’t like it. We argue that the main problems with the ‘Big Society’ relate to context rather than content; it proved easy for critics to portray it as a rationale for spending cuts, which were not envisioned when the idea was being developed, and although it provided the plausible post-Thatcherite ‘narrative’, which the Conservatives had sought in vain since 1997, it was deployed in an election battle where such a narrative was at best superfluous, and at worst a source of distraction from the perceived failings of the incumbent Labour Party.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immediately upon becoming Party leader in December 2005, David Cameron sought to ‘detoxify the Conservative brand’, in order to attract or reclaim voters who had been repulsed by the ‘greed is good’ ethos widely associated with Thatcherism. Cameron's advocacy of the ‘Big Society’ subsequently became a major element of this strategy, designed to distance him from Margaret Thatcher's professed belief that ‘there is no such thing as society’ (Woman's Own, 31 October 1987), and to persuade the public that he stood for a more compassionate and constructive mode of Conservatism.

The concept of ‘the Big Society’ was also an attempt to persuade sceptical voters that the Conservative Party now recognised that Thatcher and her ideological adherents had been mistaken in their conviction that ‘the market’ alone was the best solution to any socio-economic problem. Other measures and mechanisms were needed to address Britain's social problems, which had not been resolved by significant increases in state expenditure under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. In this context, the promotion of ‘the Big Society’ simultaneously served two crucial objectives for Conservative ‘modernisers’. First, it signified a departure or ‘moving on’ from Thatcherism, and, second, it posited a clear alternative to New Labour's alleged proclivity for tackling social problems through top-down, target-ridden, statist initiatives. In this respect, Cameron's advocacy of the Big Society purported to steer a middle way between the unfettered market and the interfering State. As Jesse Norman (2011, p. 28), a leading Conservative advocate of the Big Society, explained, ‘it contains a deep critique of the market fundamentalism of the last three decades. But, crucially, it also repudiates the state-first Fabianism of the modern Labour party’.

For its advocates, the Big Society had ‘the potential to be the most important and radical part of the coalition government's agenda’, and promised ‘to win a lasting reputation for its proponents’ (Bishop and Green, 2011, p. 30). The immediate political rewards, however, have been less tangible for David Cameron; the response of the electorate to the Big Society has been equivocal at best, and some Conservatives have expressed scepticism and even scorn. Whether or not ‘history’ will ultimately reward Cameron lies beyond the scope of the present article, although some hints can be offered on the basis of developments since the 2010 general election. Instead, our objective is to trace the intellectual origins of the idea, before concluding that, compared to other recent attempts to crystallise a partisan ‘narrative’ in a single phrase, ‘the Big Society’ has much to commend it. It is therefore pertinent to ask why it has generated so much critical comment, not least within the Conservative Party itself. Although there is no single definitive answer, we suggest some contributory factors that go beyond the short-term needs of the Party itself, including the current outlook of the British electorate at a time of economic difficulty, and more deep-rooted problems affecting the country's political process. Above all, the article challenges the fashionable view that a political party cannot hope to win office in the absence of a ‘narrative’, which combines sufficient coherence to escape damaging criticism from professional commentators, and more superficial attractions that will secure enough votes to swing an election.

The Intellectual Origins

Principled support for civil society and intermediary institutions has a long and venerable history in conservative writings, dating back to Edmund Burke's advocacy of ‘the subdivision … the little platoon’ (Burke, 1790/1986, p. 135). Although more erudite members of the Conservative Party have not forgotten Burke's exaltation of civil society, he was writing in a very different context and his views needed refinement in order to address contemporary problems.

Douglas Hurd: ‘Active citizenship’

A much more recent anticipation of the ‘Big Society’ can be discerned in the ruminations of Douglas Hurd, during his tenure as Home Secretary towards the end of the Thatcher premiership. Hurd proposed a mode of active citizenship whereby people would be encouraged to undertake voluntary work in the community, with a view to helping those less fortunate than themselves: ‘Active citizenship is the free acceptance by individuals of voluntary obligations to the community of which they are members’ (Hurd, 1989).

He seemed, indirectly at least, to be suggesting that those who had prospered the most during the Thatcher era, via generous tax cuts and higher salaries at the top, should offer something back to wider society, thus helping those who had not shared in their economic good fortune or success. As he had explained to a Bow Group dinner in 1987: ‘Conservatism is not the creed of the individual solely interested in his own bank balance. At its best it is the creed of the active citizen who works with his time and money for the general good’.

Ostensibly, Hurd's reflections on the role of the ‘active citizen’ seemed to constitute an attempt to revive the patrician ethos of noblesse oblige, which had enjoyed a proud lineage in the Conservative Party, dating back beyond the leadership of Benjamin Disraeli and influencing subsequent generations of ‘One Nation’ Tories. This mode of Conservatism asserted that the better-off ought to take an active interest in the moral and material welfare of the poor and disadvantaged, not just for Christian or humanitarian motives, but also out of enlightened self-interest; the stability and legitimacy of the (capitalist) system – and thus the position and privileges of the wealthy – would be more secure if the poorest in society were offered at least some protection against life's unavoidable misfortunes and the harsher vicissitudes of the unfettered free market. Hurd subsequently confessed that his advocacy of active citizenship partly derived from a concern that: ‘The fruits of economic success could turn sour unless we brought back greater social cohesion’ (Hurd, 2003, p. 342).

However, given traditional Conservative scepticism about extending the role of the State or imposing punitive levels of taxation on the rich in order to redistribute wealth, coupled with the perennial concern that aiding the poor might actually exacerbate ‘dependency’, there was a preference for promoting voluntary work and community involvement by ‘good citizens’. As Hurd himself argued:

We have to find, as the Victorians found, techniques and instruments which reach the parts of our society which will always lie beyond the scope of statutory instruments. I believe that the inspiring and enlisting of the active citizen in all walks of life is the key.

Hurd was therefore clearly distinguishing his notion of active citizenship from previous forms of patrician paternalism, for as he subsequently explained:

In previous centuries, when full political rights were enjoyed by few, the tradition of social obligation acted as a restraining and civilising influence upon the powerful minority. It was essentially aristocratic. Now that we have universal suffrage, general prosperity, and much greater equality of opportunity, we need to encourage the notion that civic responsibilities, too, are the property of all. (Hurd, 1988)

Or as he expressed it the following year, Britain had not only ‘democratised the ownership of property’: it had also made possible the ‘democratisation of responsible citizenship’, so that what had once been ‘the duty of an elite’ had now become the ‘responsibility of all who have time or money to spare’ (Hurd, 1989).

Through such active citizenship, the poor could be provided with practical help and advice, thereby enabling them to become more self-reliant or successful – an objective promoted by bodies such as the nineteenth-century Charity Society Organisation. Hurd's ideas on this subject deserve close scrutiny, given his prominence within the Conservative Party and the route that had taken him there. Having been a loyal and invaluable aide to Edward Heath, Hurd saw the failings of the post-war ‘consensus’ at close quarters and was able to rise within Mrs Thatcher's Conservative Party without ever becoming ‘one of us’. His tentative thinking on active citizenship – expressed at a time when less thoughtful Conservatives tended to assume that ‘Thatcherism’ had been an unqualified success – can be seen as the product of continued learning by a seasoned and sensitive politician.

When David Cameron first entered the House of Commons in 2001, he did so having been elected by Hurd's former constituents in Witney, Oxfordshire. This coincidence is a long way from proof of direct influence, but there are clear points of similarity in the suggestions of Hurd and Cameron of a less self-centred alternative to Thatcherism – to the extent that they are equally vulnerable to the accusation that their variety of civic activism is an option only available to the affluent. This is certainly a criticism discernible in a report published by the New Economics Foundation, which noted that:

Building this ‘Big Society’ depends crucially on people having enough time to engage in local action. While of course everyone has the same number of hours in the day, some have a lot more control over their time than others. People with low-paid jobs and big family responsibilities … tend to be poor in discretionary time as well as money. [in the case of the unemployed] Committing time to unpaid local activity would put many at risk of losing benefits that depend on actively seeking full-time employment … . In short, long hours, low wages and lack of control over how time is spent undermine a key premise of the ‘Big Society’, which is that social and financial gains will come from replacing paid with unpaid labour. (Coote, 2010, pp. 16–17)

Such considerations have led some critics to warn of a ‘postcode lottery’, whereby the civic altruism and active citizenship envisaged by proponents of the ‘Big Society’ become ‘the haphazard driving force for wide local variations in volume, focus and quality of support … corresponding more closely to the interests, availability and generosity of local residents than to the nature and levels of actual service need’ (Evans, 2011, p. 167).

David Willetts: Civic conservatism

Hurd recalls that when he was invited to the inaugural meeting of the strategy group chaired by Margaret Thatcher in the summer of 1986, he was ‘the only one to favour anything on service and neighbourliness’ (Hurd, 2003, p. 341). Mrs Thatcher made some favourable private comments about one of his later speeches on this theme, but ‘more I think because of some favourable headlines than because she had read and agreed with it’ (Hurd, 2007, p. 3). Despite the headlines Hurd's ruminations had no immediate impact on party thinking; they aroused little public discussion even in November 1990 when he contested the party leadership. However, during the dog days of John Major's disintegrating Government in the mid-1990s, a then junior minister, David Willetts, began contemplating how Conservatives should adapt to life after Thatcher. Although it had hitherto been widely assumed (inside the Conservative Party and among commentators and academics) that there were basically two options after 1990 – namely adhering to Thatcherism or reverting to One Nation Toryism – Willetts followed Hurd in seeking to develop a more nuanced alternative for his party, one that aimed to meld a continuation of economic liberalism with a greater concern for social issues (for an overview of Willetts’ thinking since 1990, see Garnett and Hickson, 2009: chapter 10).

Willetts acknowledged the need for a more constructive Conservative approach to socio-economic deprivation and cognate social problems, rather than merely advocating further extension of free markets and continued reliance on the much-vaunted ‘trickle down’ effect. An indication of the extent to which he had begun to engage in such a re-examination of contemporary Conservatism during the 1990s was revealed by the shift both in emphasis and tone between his 1992 book Modern Conservatism and his 1994 pamphlet, Civic Conservatism.

In both publications, Willetts insisted that there was no intrinsic incompatibility between the free market and civil society, and as such, he emphatically rejected the allegations of critics – not only on the Left, but also among One Nation Conservatives and some former supporters of the New Right – that ‘the market’, competition and individualism were destructive of the stable communities and social institutions which Conservatives had traditionally revered (see, for example, Gilmour, 1992; Gray, 1995, pp. 147, 149; Gray, 1997, pp. 3–65; Worsthorne, 2004). However, closer examination of the two publications reveals that whereas the emphasis in Modern Conservatism was on the primacy of the free market, 2 years later Willetts ascribed greater importance to communities and civic institutions. Having privileged the economic sphere, Willetts was now willing to grant a higher priority to the social domain; there definitely was such a thing as society after all.

In Modern Conservatism, Willets had insisted that civil society and communities needed free markets, not least because the alternative, state control, would itself destroy free and voluntary institutions. Only the minimal state associated with economic liberalism could permit the flourishing of a range of intermediate institutions. Although Willetts continued to praise the free market in Civic Conservatism, he now acknowledged that ‘we are not so confident’ about the ability of the market to solve social problems or achieve non-economic objectives. Remarkably, he even confessed that there were probably ‘many good Conservatives who must be regarded as sharing’ Marx's view that ‘in modern capitalism, all relationships become “commodified”’. Willetts recognised that after 15 years of economic liberalism and the relentless promotion of markets (even in what remained of the public sector), ‘Contract culture appears to have triumphed, and accountants rule; that leaves many traditional Conservatives feeling uneasy’. Even some neo-liberals were now recognising that ‘the idea of the economic agent makes little sense unless that agent is embodied in a culture with a set of values’ (Willetts, 1994, pp. 7, 54).

From this revised perspective, Willetts suggested that the new challenge facing Conservatives was ‘to formulate a coherent set of policies which shows that, as well as for the individual, there must be a role for collective action’. Crucially, he was quick to emphasise that ‘collective action does not necessarily mean state action’ (Willetts, 1994, p. 23. See also, Willetts, 2002, p. 55). While avoiding specificity – this was, after all, a speculative exposition, intended to contribute towards an intra-party debate over the future of Conservatism – Willetts referred to the need to reinvent society's ‘little platoons’, by which he meant the range of intermediate institutions – a blend of local, private, public and voluntary organisations – which simultaneously stood between, yet indirectly linked, individuals and the state. In so doing, he addressed a notable One Nation concern about Thatcherism, which Ian Gilmour had articulated 2 years earlier, namely the manner in which it had eviscerated intermediate institutions. As Gilmour had written, ‘It is these buffers between the individual and the state which preserve liberty by preventing a direct confrontation between them. When they are swept away, tyranny or anarchy follows’ (Gilmour, 1992, p. 199).

Ferdinand Mount: Reviving philanthropic voluntarism

Also hoping to influence post-Thatcherite Conservatism during this period was Ferdinand Mount, who had briefly headed Thatcher's Downing Street Policy Unit in the early 1980s. Mount had never been a card-carrying Thatcherite – he had favoured William Whitelaw in the 1975 Conservative leadership contest, and thought that ‘some of Mrs Thatcher's enragés were decidedly swivel-eyed’ (Mount, 2009, pp. 287, 299). After Mrs Thatcher's ejection from office he too was seeking to chart a course between an over-mighty State and the unfettered market. Mount suggested that ‘the relationship between State, commerce [private enterprise] and the voluntary sector’ should be viewed as ‘a virtuous triangle’; as such, ‘we must re-learn that each sector has its own virtues and failings, and that they must co-operate and compete with one another, and do so in a good-humoured and open-minded spirit’ (Mount, 1993, pp. 15, 17).

Mount called for a major revival of the altruistic and philanthropic voluntary action, which the welfare state had relentlessly abrogated for itself; ‘whereas a hundred years ago it was the State that was filling in the gaps not provided for by voluntary action, in recent years it has been voluntary action filling in the gaps left by the State’. This imbalance needed to be recalibrated through reviving the voluntary principle, and thereby crafting a ‘third way’, a ‘non-state, non-commercial, co-operative endeavour’ (Mount, 1993, pp. 6, 13). The similarity between these views and David Cameron's ‘Big Society’ is particularly interesting since Mount's cousin Mary is the Prime Minister's mother; but the difficulty of establishing direct influence remains. Mount himself doubts whether Cameron or any of his supporters ever read his pamphlet, and feels that the voluntary principle was a common element to all the main British ideological traditions that had been obscured during the over-simplified battle over the claims of the free market and the state (correspondence with authors, 22 March 2012). Ironically, this denial of direct influence reinforces the congruity between Mount's overall message and the arguments of later writers like Phillip Blond.

Damian Green: A smarter state

Nearly a decade after Mount had tried to rehabilitate the voluntary principle, the Conservative MP (and later junior Minister in the Coalition) Damian Green argued that markets alone were not enough, and that ‘Britain has obviously moved on from the era of radical individualism’. It was vital for the Conservative Party to develop ‘a new intellectual settlement which will make us once again the guardians of the One Nation philosophy’ – an aspiration made easier by New Labour's failure to make serious inroads into socio-economic inequality. However, while emphasising that Conservatives urgently needed to promote more constructive policies to tackle social problems, Green was adamant that while this should not entail a revival of extensive state intervention, neither would it suffice to keep rolling back the state: ‘What we need is a better state, not simply a smaller one’, one whose primary role vis-á-vis tackling poverty and associated social problems would be to promote and co-ordinate a range of non-state or sub-national institutions. This was neatly linked to a growing and parallel Conservative emphasis on localism, which, Green insisted, would provide ‘space for non-state institutions to flourish’ in those communities that suffered most from socio-economic deprivation and social disadvantage (Green, 2003: passim).

It was particularly noteworthy that Green should re-affirm his well-known affiliation with the party's ‘One Nation’ tradition while expressing his support for voluntarism. As Willetts hailed from the Thatcherite wing of the party, the growing congruence in their views suggested that civic activism could provide the practical basis for a reconciliation between party factions, which had been at loggerheads over fundamental principles since the mid-1970s. A leader who could find a fitting slogan or sound-bite to encapsulate these convergent views would thus have a chance to persuade the electorate that in this respect, at least, the party had put aside its feuding in a manner which might mollify voters who had been alienated by the more rugged Conservative individualists of the 1980s.

Oliver Letwin: The neighbourly society

Also promoting this new Conservative approach, after the Blair Government's re-election in 2001, was Oliver Letwin, who began emphasising the need to revive ‘neighbourliness’ as part of a more general strategy to develop a form of ‘civic’ or communitarian Conservatism. In a series of speeches, Letwin argued that tackling the myriad social problems of contemporary Britain required a multi-agency approach, encompassing a range of individuals and institutions, of which the state itself would constitute merely one part. Indeed, the state's primary role would be to facilitate necessary action by other agencies and civic bodies, including the voluntary sector, rather than seek to address such problems itself. As the New Labour state was deemed to be an integral part of Britain's current plight: ‘The object of policy must be to bolster those institutions’, which could create the neighbourly society through empowering communities and local citizens, and fostering greater individual and social responsibility (Letwin, 2003, p. 11).

Letwin criticised Labour's penchant for ‘top-down’ strategies, reflecting its assumption that Whitehall initiatives can solve any societal problem. Such an approach not only erodes the professionalism and authority of front-line staff that might otherwise be able to tackle some of the problems themselves, but also disempowers local citizens and private individuals who, with regard to anti-social behaviour, for example, might otherwise be prepared to confront law-breakers and wrong-doers in their communities. By contrast, Letwin emphasised, Conservatives advocated ‘bottom-up’ responses to tackle social maladies, and in so doing, empowered individuals and local communities, whereas Labour emasculated them (Letwin, 2003, p. 41).

Like Willetts, Letwin had been regarded in the 1980s as a leading intellectual exponent of Thatcherism, and so his modified views could be welcomed as the product of serious reflection on some of the socially damaging consequences of unfettered economic liberalism, and an acknowledgement that a more constructive social policy needed to be developed by the Conservative Party.

Iain Duncan Smith: Searching for social justice

The other key progenitor of a new mode of Conservatism before Cameron's election as Party leader was Iain Duncan Smith, who, once he was freed from the constraints and responsibilities of being Conservative leader (from 2001 to 2003), devoted himself to addressing poverty and social disadvantage. The main vehicle for his message has been the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ), which aims to ‘put social justice at the heart of British politics and to build an alliance of poverty-fighting organisations in order to see a reversal of social breakdown in the UK’.

Inaugurated by Duncan Smith himself in 2004, the CSJ is formally an independent (that is, non-political) think tank – although some senior Conservatives, most notably Letwin, Willetts and William Hague, sit on its Advisory Board. The name itself is especially significant, because Conservatives have traditionally been deeply suspicious of ‘social justice’, invariably viewing it as a euphemism for ‘equality’ (see, for example, Cecil, 1912, p. 182; Bryant, 1929, p. 7; Maude, 1969, p. 129; Hailsham, 1978, p. 117; Willetts, 1992, p. 112; see, also, Hayek, 1976; 1988). Its working groups and task forces attracted a range of individuals with professional experience or knowledge of the issues they were investigating. Between its inauguration in 2004 and the end of 2009, the CSJ produced 43 policy papers and reports, addressing such topics as the causes of crime, children in care, gambling, good parenting, personal debt, the role of the voluntary sector and welfare dependency.

One of the key themes developed by the CSJ, and which was subsequently promulgated by the Conservative leadership to attack the Blair–Brown Governments, was that of ‘Broken Britain’. This emerged when David Cameron, shortly after becoming Conservative leader in December 2005, commissioned the Centre to undertake a major inquiry, which would provide the basis for policies to promote social justice and tackle poverty. This inquiry, comprising three discrete phases, commenced with an evaluation of the nature and extent of social breakdown and poverty, before examining the underlying causes. The third and final phase was to propose policies for tackling the inter-related problems of poverty, social breakdown and social exclusion.

When the ensuing 671-page Breakthrough Britain report was published in July 2007, the policy proposals were wholly commensurate with the new Conservative emphasis on promoting or reviving civic, non-state, institutions as the primary means of addressing social problems. In so doing, they not only reaffirmed the Conservative leadership's recognition that markets alone were not enough; they also posited a clear distinction between ‘society’ and ‘the state’. Cameron and his fellow modernisers were able to differentiate the Conservative Party's approach to tackling poverty and social exclusion from that of New Labour, which was still deemed to be instinctively and irrevocably state-centric, top-down and target-driven.

Thereafter, this became a central Cameron theme, as indicated by his speech to the 2008 Conservative conference, when he declared that:

For Labour there is only the state and the individual, nothing in between. No family to rely on, no friend to depend on, no community to call on. No neighbourhood to grow in, no faith to share in, no charities to work in. No-one but the Minister, nowhere but Whitehall, no such thing as society – just them, and their laws, and their rules, and their arrogance. You cannot run our country like this.

It was a neat rhetorical device: armed with their renewed faith in intermediate institutions, Conservatives could now turn the tables and accuse Labour of not believing in such a thing as ‘society’. At the same time, the new approach enabled the Cameron-led Conservative Party to reaffirm its move beyond Thatcherism, as was evident in Oliver Letwin's insistence that ‘Conservatives have never been arid, atomistic, individualistic libertarians’ (Letwin, 2003, p. 44). Instead, this narrative asserted that whereas the 1979–1997 Conservative Governments had enacted the economic measures and reforms that had become necessary to tackle the country's immediate problems, in the early twenty-first century, the ‘biggest long-term challenge we face … is a social one … as great as the economic revolution that was required’ in the previous two decades. Owing to these economic reforms (and in spite of the economic recession of 2008–2009) Letwin claimed that ‘we are now a rich country again. Yet a worrying proportion of the population has been left behind … a section of the population living in multiple deprivation’, a situation that he readily conceded was ‘morally wrong … there is something immoral about people being left behind’ (Letwin, 2009, pp. 71, 73, 76).

In accordance with this new Conservative emphasis on communities and localism, Letwin echoed Cameron in emphasising that ‘the responsibility of the state is to encourage corporations, individuals and communities to do things that are pro-social to help solve the problem of multiple deprivation’. It would also be necessary to establish ‘frameworks that persuade corporations to behave in a socially responsible way’. Yet in avoiding statist or statutory measures as far as possible, Letwin acknowledged that government should chiefly rely on exhortation and persuasion ‘to encourage the social norms of giving’. This, he explained, was why the Conservative leadership had recently become interested in the concept of ‘nudge economics’,Footnote 1 which he characterised as being ‘about giving a gentle push to society to move in a direction of greater responsibility, or greater coherence, or kindliness’ (Letwin, 2009, p. 76). Ultimately, Letwin maintained that social problems had to be tackled by ‘setting people – neighbourhoods, schools, hospitals, professionals, patients, pupils, teachers, everyone everywhere in this country – free to act, together or individually, with a helping hand from the State but without the dead hand of bureaucracy upon them’ (Letwin, 2003, p. 46).

Phillip Blond: ‘Red Toryism’

The Conservative leadership's endeavours to craft a ‘civic Conservatism’ were given additional intellectual impetus by the work of Phillip Blond, until 2008 an academic based at Cumbria University. A series of articles on what he termed ‘Red Toryism’ brought Blond to the attention of senior Conservatives, for whom he reportedly began writing speeches. He also became, in January 2009, head of the newly established ‘Progressive Conservatism’ project at Demos, a think tank, which (although not formally aligned to any political party) had hitherto been widely associated with New Labour, and saw itself as a progenitor of progressive political ideas and policy proposals. Blond subsequently established a separate think tank, ResPublica, which was officially launched in November 2009.

Blond's most significant contribution to the ‘post-Thatcherite’ critique was to develop an historical context for Britain's problems under New Labour, which candidly recognised the culpability of Thatcherism itself. He insisted that, in 2009, British politics was in the midst of a paradigm shift, for ‘just as 30 years ago we saw the end of Keynesianism’, today: ‘We are witnessing the end of the neo-liberal project’. Whereas ‘1979 brought an end to the welfare state, 2009 will see an end to the market state, and the next election will, with the election of a Conservative government, usher in the birth of the civic state’ (Blond, 2009a, p. 1). According to Blond, contemporary Britain was suffering from nearly seven decades of excessive statism, liberalism and individualism, which had served to destroy civic institutions, community cohesion and social responsibility. Although statism is ostensibly incompatible with liberalism and individualism, Blond insisted that all three had been pursued at various junctures since 1945, but with the same destructive consequences, and in this respect, he attacked both the Left and the New Right.

Blond argued that when the post-1945 welfare state was established, it effectively ‘aborted all the pre-existing working-class societies, from the self-help societies to insurance societies, co-operative societies and all those ideas about working-class mutuality that are about … building social capital’ (quoted in Long, 2009, p. 5; see also Blond, 2009b, pp. 81–82). However, under Thatcher and Major there was a paradigm shift to economic liberalism, individualism and consumerism, and this was not seriously challenged by the subsequent 1997–2007 New Labour Governments led by Tony Blair. Blond insisted that the Conservative Governments of the 1980s and 1990s themselves promoted a socially damaging form of liberalism that venerated the pursuit of self-interest, based on markets and materialism and a ‘rolling back of the state’. As such, whereas Old Labour had undermined civil society and communities by the role it ascribed to central government and the state, Thatcherite Conservatism was destructive of civil society and communities by privileging markets and individuals over the social realm.

Furthermore, instead of facilitating a ‘trickle down’ of wealth, in accordance with the claims of Conservative economic liberals and New Right devotees of Friedrich von Hayek, the market state of the 1980s and 1990s served to ensure that ‘wealth flowed upwards rather than downwards’, whereupon ‘the ability to transform one's life or situation steadily declined’ (Blond, 2009a, p. 2). Britain has thus witnessed the emergence both of a ‘super-rich’ whose wealth and lifestyles are such that they are increasingly detached from mainstream British society, and an ‘underclass’, which is also socially detached, but owing to a paucity of material resources and opportunities.

In their own way, therefore, ‘the market’ and contemporary ‘monopoly capitalism’ have disempowered individuals and fuelled social fragmentation just as the welfare state and nationalisation had done (Blond, 2009b, pp. 83–87). To tackle these problems, Blond urged the Conservative Party to place a strong emphasis on ‘localism’ and ‘communitarian civic Conservatism’, the latter concerned with creating or reviving Burke's ‘little platoons’ – which Blond explicitly evokes (Blond, 2009c, p. 33) – of private, public and voluntary associations and institutions, which have been undermined by the lethal cocktail of bureaucratic statism, monopoly capitalism and nihilistic individualism. Although the state will sometimes need to provide a framework or ‘steer’ to facilitate appropriate policies, measures to tackle poverty and social exclusion should be based, wherever possible, on voluntary action and bottom-up initiatives.

Cameron and the ‘Big Society’

David Cameron himself did not start talking specifically about the ‘Big Society’ until autumn 2009, by which time Britain was well into a recession precipitated by the previous year's international banking crisis. Hitherto, the Conservative leader had insisted, on various occasions, that ‘there is such a thing as society, but it is not the same thing as the state’. Indeed, this form of words had been deployed in the introduction to the Built to Last statement of Conservative aims and values, which heralded Cameron's modernising agenda (Conservative Party, 2006, p. 1). The phrase was particularly significant because it sought to distinguish Cameron's vision of Conservatism from the ‘no such thing as society’ perspective symbolised by Thatcherism, while also attacking Labour's over-reliance on statist solutions to social problems; ‘we do not believe that it is through centralised government alone that we can change society for the better’. Instead, Built to Last recommended ‘Setting social enterprises and the voluntary sector free to tackle multiple deprivation’, by ‘removing the barriers that hold back the expansion of the social enterprise sector, community organisations, voluntary bodies and charities’, while also creating ‘a level playing field with the public sector’ (Conservative Party, 2006, pp.5, 10).

The general orientation of these early pronouncements was wholly commensurate with the ‘Big Society’, but the best-publicised exposition of this concept was Cameron's Hugo Young Lecture of November 2009. Cameron used the occasion to attack New Labour for constantly extending the role of the State, with deleterious consequences both for millions of individuals and for British society as a whole. He alleged that after 12 years of a Labour government:

… the size, scope and role of government in Britain has reached a point where it is now inhibiting, not advancing the progressive aims of reducing poverty, fighting inequality, and increasing general well-being. Indeed there is a worrying paradox that because of its effect on personal and social responsibility, the recent growth of the state has promoted not social solidarity, but selfishness and individualism.

Although (unlike Blond) Cameron did not admit that his party was as much to blame as Labour for this state of affairs, he did not simply demand a ‘rolling back’ of the state in familiar Thatcherite fashion. Rather, he called for ‘a thoughtful re-imagination of the role, as well as the size, of the state’. He envisaged a reformed state ‘actively helping to create the big society; directly agitating for, catalysing and galvanising social renewal’. In this renewed form, the state could play a key role in ‘empowering and enabling individuals, families and communities to take control of their lives’ (Cameron, 2009, emphasis added).

Cameron returned to this theme – ‘a big idea … a guiding philosophy’ – in several subsequent speeches, such as that delivered in March 2010 (just days before Gordon Brown called a general election for 6 May), when the Conservative leader explained that the Big Society ‘includes a whole set of unifying approaches – breaking state monopolies, allowing charities, social enterprises and companies to provide public services, devolving power down to neighbourhoods’, all of which were deemed to herald a bold and stark alternative to Labour's paternalism and state control (Cameron, 2010). Cameron attributed this proposal for local grass-roots activism to his chief strategist, Steve Hilton; yet, as we have seen, the assumption that the thinking behind the ‘Big Society’ had only emerged from within the leader's own entourage, rather than reflecting a long-established trend of thought among senior Conservative politicians, was misleading. Significantly, though, it was an assumption that seemed to be shared by many of those Conservatives who disliked Cameron's leadership and the ‘Notting Hill set’ associated with it (Brown and Blatchford, 2011, p. 43). Such critics of Cameron's style found it very easy to transfer their antipathy to his ideas, whether or not they would have embraced them if they had been articulated by someone with more tangible Thatcherite credentials.

In the ‘Foreword’ to the Conservative Party's 2010 election manifesto, a change was promised ‘from big government to Big Society’, and ‘from state action to social action, encouraging social responsibility … supporting social enterprises with the power to transform neighbourhoods’ (Conservative Party, 2010, pp. vii, viii). Among the specific ‘Big Society’ measures pledged in the manifesto were:

-

To establish a Big Society Bank, funded from dormant bank accounts, to support neighbourhood groups, charities, social enterprises and other non-governmental bodies.

-

Permit non-state organisations to share in the delivery and provision of public services.

-

Give public sector workers ownership of the services they deliver, by allowing them to establish cooperatives and ‘mutualisation’ in education and health, and letting them bid to take over the services they run.

-

Allow parents to establish their own ‘free’ schools.

-

Allow communities to take over the management of local amenities, such as libraries and parks.

-

Transform the civil service into a ‘civic service’ by ensuring that participation in social action is recognised in civil servants’ appraisals.

-

Promote the creation and development of neighbourhood groups, which can take action to improve their local area. Cabinet Office funds to be provided to train independent community organisers to establish and manage these neighbourhood groups.

-

Launch a National Citizen Service that will, initially, provide a programme for 16-year-olds to provide them with the opportunity to develop the skills needed to be active and responsible citizens, and become involved in their communities.

These initiatives, it was claimed, would create or re-establish ‘the “little platoons” of civil society – and the institutional building blocks of the Big Society’ (Conservative Party, 2010, pp. 27, 37–39; see also Norman, 2010). They also promised to refute from the outset any allegations that the idea amounted to no more than a vacuous slogan, devoid of concrete policy implications, making the Big Society ‘as hard to catch as a rainbow’ (Brown and Blatchford, 2011, p. 43).

Altogether, the potential political advantages of the ‘Big Society’ were numerous; indeed, in summary form, they might well constitute an ideal wish-list for any Conservative seeking an idea that would neutralise the party's chief electoral handicaps since the days of the Poll Tax in the late 1980s:

-

The phrase itself suggested that the Conservatives believed in such a thing as ‘society’, and had thus moved on from Thatcherism.

-

At the same time, it offered ‘clear blue water’ between the Conservatives and ‘New’ Labour, by emphasising that society is not the same thing as the state.

-

If circumstances demanded, it could thus be used as a theoretical justification for a reduction in the scope of state activity, creating the potential for subsequent tax cuts.

-

It implied a strong faith in the civic spirit of the British people (and if, in practice, it betrayed a tacit equation of ‘the British people’ with ‘middle-class Britons’, this would have the effect of appealing to ‘core’ Conservative voters while reaching out rhetorically to other key social groups).

-

The ‘Big Society’ was not a new invention, and it had not been borrowed from non-Conservative sources. Rather, it represented a revival of ideas, which had been influential among those Tories who had been instrumental in changing the name of their party to ‘Conservative’ in the 1830s.

Melding the ‘Big Society’ With the Liberal Democrats’ ‘Localism’

After the May 2010 election, another reason emerged to suggest that Cameron had alighted on an inspired slogan. In the first decade of the present century, the Liberal Democrats had been re-examining their own ideological heritage. The Orange Book (2004) contained contributions from several highly promising or established Liberal Democrat politicians, many of whom explored the theme of ‘localism’, which could easily be reconciled with emerging Conservative ideas about the ‘Big Society’. At the same time, the prevailing tone of the book suggested that some Liberal Democrats were moving closer to Conservative terrain in their thinking about the role of the state vis-a-vis the free market. The trend gathered pace after the 2005 general election, despite the fact that the Liberal Democrats were widely perceived to have prospered because their official policies seemed to outflank even Labour in their enthusiasm for ‘tax and spend’ policies. Thus, in 2007 Chris Huhne appealed to an older strand of liberalism by rejecting ‘statist’ centralism in favour of a brand of localism, which would ‘allow local authorities to experiment with different types of provider: with traditional public-service providers, with mutual, cooperatives and social enterprises, and with social companies’ (2007, pp. 246–247). Similar arguments had been advanced previously by Ed Davey (2004: chapter 2), one of Huhne's parliamentary colleagues.

When the electorate failed to deliver a conclusive verdict in the 2010 general election (for an account of why the Conservatives failed to win an outright victory, see Dorey, 2010; Dorey et al, 2011: chapter 6), it was generally thought that, if the Liberal Democrats had been asked to choose between Labour and the Conservatives as potential coalition partners, their clear preference would have been for a Lib-Lab arrangement. However, quite apart from the parliamentary arithmetic, a comparison of the Orange Book and the ‘Big Society’ suggests that – for many senior Liberal Democrat MPs, at least – the Conservatives offered the only credible opportunity for a more constructive and congenial alliance. It seems that David Cameron had had little personal contact with Nick Clegg before the election campaign. However, the personal chemistry between the two leaders, which became evident immediately after the election, was arguably less important than their shared enthusiasm for localism and non-state solutions to social problems. Cameron's refusal to give up the ‘Big Society’ slogan, despite the ill-concealed reservations of some colleagues, can only have helped convince Clegg that they had much in common. The ‘Big Society’ was one way of delineating a zone of ideological convergence within which the leaders could engage in creative thinking, distinguishing their parties sharply from Gordon Brown's Labour Party, which had talked about localism without enacting any significant measures to promote it.

A Mixed Reception

Despite the ‘moment of crystallisation’ shared by Clegg and Cameron after the 2010 election result had effectively forced them together, a serious problem that Conservative modernisers have encountered in their advocacy of the Big Society is that their enthusiasm and vision have not been more widely shared, either in the Conservative Party, or among the British electorate. Indeed, some critics believe that the ‘Big Society’ has suffered from being too nebulous or ill-defined, while others purportedly know what it is, but are hostile or suspicious as a consequence (for a cursory overview of these various criticism, McVeigh, 2010, p. 33; Sylvester, 2011, p. 19).

The Conservatives

Despite the abstract advantages enjoyed by the ‘Big Society’ as a campaigning slogan, a philosophical foundation for a legislative programme, and a basis for cooperation with the Liberal Democrats, in practice the concept was not universally welcomed within Cameron's own party. For understandable reasons, the most outspoken critics held their fire until the election was over, but the views expressed soon afterwards suggested that the reservations were real. Eric Pickles (the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, and thus politically central to much of the Big Society agenda), reportedly joked that the Big Society would mean that: ‘When the spaceship arrives from Alpha Centauri and lands in the middle of Barnsley, and goes up to number 23 Acacia Avenue, and the spaceling says to the lady that answers the door: “take me to your leader”, she would say: “I’m in charge”’(quoted in Bishop and Green, 2011, p. 30). An (unnamed) senior Conservative more crudely complained that: ‘The “big society” is bollocks. It is boiled vegetables that have been cooked for three minutes too long. It tastes of nothing’ (quoted in Watt, 2010). Another un-named senior Conservative was equally contemptuous, claiming that the ‘Big Society’ was ‘complete crap … . We couldn’t sell that stuff on the doorstep. It was pathetic. All we needed was a simple message on policy. We could have won a majority if we had not had to try to sell this nonsense’ (quoted in Helm and Asthana, 2010).

Certainly, some post-mortems on the 2010 general election campaign featured claims that the Conservatives could have won an overall majority had Cameron not placed so much emphasis on promoting the Big Society, at the expense of more perspicacious and supposedly potent issues. For example, a post-election poll conducted by ConservativeHome (a renowned blog/web-site run by a former member of Conservative Central Office, Tim Montgomerie) revealed that 71 per cent of 109 party candidates polled believed that the Big Society ‘should never have been put at the heart of the Tory election campaign’, while 62 per cent believed that the Party ‘never developed a strategic message’ for the 2010 election (ConservativeHome, 2010, p. 36; see also Ashcroft, 2010, p. 123; The Sunday Times, 8 August 2010; Scholefield and Frost, 2011). Such criticisms were reiterated towards the end of David Cameron's first year as Prime Minister, with Tim Montgomerie reporting that in a poll of 1500 Conservative Party members, 25 per cent adjudged the electoral emphasis on the Big Society as one of Cameron's biggest mistakes since becoming leader in December 2005. Indeed, it was deemed a bigger error than Cameron's failure to support the revival of grammar schools, his pre-2010 socially liberal stance on law-and-order, and the refusal to make immigration a more prominent issue in the election campaign. Montgomerie (2011) concluded that: ‘In a close election a successful party needs a potent, readily understandable message. Rather than finding that message the Tory manifesto promised to build a Big Society’.

The implication was that the thinly disguised Thatcherism purveyed by the Party in 2001 and 2005 – and summarily rejected by the electorate – would have proved ‘potent’ in 2010; and, as Cameron was obviously ill-equipped to deliver a ‘readily understandable message’ of that nature, the Conservatives would have fared better under a more right-wing leader who spelt things out plainly rather than sounding ‘too clever by half’. While it is impossible to disprove this analysis, the ill-fated ‘dog-whistling’ of Conservative strategists in 2001 and 2005 suggest that it is profoundly implausible. In fact, Conservative criticism of the ‘Big Society’ was almost uniformly superficial, suggesting that Cameron's internal opponents wanted to laugh it out of court before more objective observers took the trouble to analyse it.

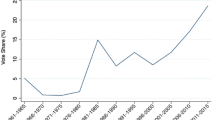

Meanwhile, various polls in the approach to the 2010 general election suggested that many voters liked or trusted David Cameron more than they liked or trusted the Conservative Party itself. This suggests that not enough voters were yet persuaded that Cameron had ‘detoxified’ the Conservative brand sufficiently to allow them to accept his initiative as anything but a rhetorical cloak for government; and the response of his own foot-soldiers to the ‘Big Society’ initiative indicates that many of them had no desire to be detoxified.

The electorate

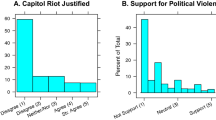

The survey evidence concerning the ‘Big Society’ suggests that the concept may indeed have been difficult to ‘sell’ to voters on the doorsteps, but by no means impossible for any canvasser who was prepared to give the concept a fair trial. As Table 1 illustrates, there was widespread agreement among voters on the general principle that people ought to have greater control over the delivery of public services at local level (with over half of respondents expressing strong agreement). However, assent to this proposition declined when the caveat was added that this would cause local variations in service provision. Only 29 per cent of respondents still ‘strongly agreed’ when this important implication was highlighted (although an additional 34 per cent ‘tended to agree’, ensuring an overall clear majority in favour of localism).

Meanwhile, although virtually half of respondents ‘strongly agreed’ that people ought to get more involved in their communities, this figure dropped to 28 per cent when respondents were asked whether they themselves ought to contribute. Furthermore, although a total of 86 per cent of respondents concurred (either by ‘strongly agreeing’, or ‘tending to agree’) with the proposition that people ought to get more involved in their communities and assist in the provision of public services at local level, the same poll revealed that 60 per cent thought that tackling social problems and delivering public services was the responsibility of government, and that consequently, politicians should not be calling on the public to help.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, public scepticism relating to the Big Society was exacerbated in the context of the Coalition Government's austerity measures and planned public expenditure cuts. For example, an early 2011 ComRes poll (jointly commissioned by the Independent on Sunday and the Sunday Mirror, 13 February 2011) revealed that 41 per cent of the public believed that the Big Society was ‘merely a cover for spending cuts’, with only 21 per cent of respondents disagreeing with this view. The poll also reported that 50 per cent of voters considered the Big Society to be largely ‘a gimmick’, and only 17 per cent believed that it would genuinely foster a ‘culture of volunteering’. Moreover, only 16 per cent of respondents expected the Big Society to ‘redistribute power from central government to ordinary citizens’.

Further evidence of continued public scepticism about the Big Society was evident in an autumn 2011 YouGov poll, published in YouGov poll (4 September 2011), which gauged public opinion concerning the Coalition's flagship education policy, whereby parents were encouraged to establish and manage their own ‘free schools’. Only 35 per cent of those questioned supported the creation of such schools, with 38 per cent opposing them, and 27 per cent unsure either way. Moreover, only 18 per cent of respondents said that they would be interested in helping to set up and run a free school in their area, while 62 per cent reported that they would not be interested. Clearly, such findings did not bode well for the ‘active citizenship’ on which much of the Big Society vision depended. However, they emphatically do not provide any support to those Conservatives who think that the party would have fared better in the 2010 general election if their campaign had revolved around the more simplistic ‘Thatcherite’ message recommended by Cameron's internal critics, as they indicate strong public support for state provision in these areas even if the management was freed from local government control.

The auguries for the success of the Big Society look increasingly bleak, although therein lies a paradox. In principle, the professed need to ‘shrink the state’ in order to eradicate the fiscal deficit provides an ideal opportunity for the civic institutions of the ‘Big Society’ to fill the growing gaps in social provision. Yet many of these local or sub-national bodies are themselves having their budgets cut, as if to lend a perverse credence to the mantra that ‘we’re all in this together’. Consequently, not only will many of these civic institutions themselves increasingly lack the requisite resources to fulfil the roles expected of them in delivering support and services to the socially disadvantaged or excluded, they too will probably join the growing chorus of criticism once the impact of the imminent cuts becomes more widely visible. In fact, some commentators believe that this process is already underway:

In the early days of the Coalition, before the Spending Review had revealed the true horrors of the fiscal squeeze to come, the Big Society could bask in the warm glow that comes from being associated with charities, voluntary groups and philanthropy. Once the full scale of the cuts became apparent, and the voluntary sector realised they were not immune, the mood rapidly turned sour. (Brown and Blatchford, 2011, p. 45)

This souring of the mood will doubtless reinforce an already widespread suspicion that the ‘Big Society’ is little more than ideological cover or a political smokescreen for deep cuts in public services and welfare provision. Moreover, if the ‘Big Society’ fails to materialise or ameliorate the impact of cuts to public services, then David Cameron's efforts to ‘detoxify’ the Conservative brand are likely to have been in vain, and a growing number of critics will claim that ‘the nasty Party’ is back with a vengeance’.

Certainly, there remains considerable scepticism about the ‘Big Society’, even among Conservative voters. As Table 2 shows, only 32 per cent of those polled claimed to know about the ‘Big Society’ either ‘very well’ or ‘fairly well’, a mere 3-point increase on the same question in May 2011. Meanwhile, less than half of Conservative voters expressed such awareness, although some Conservatives might have expressed a positive view for partisan reasons, just as some Labour supporters might have expressed lack of understanding in order to make a political point.

Probably the most revealing statistics concern the responses to the question about whether or not the ‘Big Society’ is likely to prove successful, for no less than 73 per cent of respondents prophesied that it ‘would not work’, with only 9 per cent envisaging it proving successful. Among Conservative voters, only 20 per cent believed that the ‘Big Society’ would work, compared to 57 per cent of Conservatives who believed that it would not.

A further blow to the ‘Big Society’ concept came in March 2012, when Steve Hilton – hitherto Cameron's closest ‘blue skies’ thinker and chief strategist – resigned. It has variously been suggested that one of the main reasons for Hilton's resignation was his growing frustration at the slow pace of many government reforms, partly due to bureaucratic inertia or obstruction. The ‘Big Society’ could prove to be the main casualty of Hilton's departure.

Conclusion: No Need for ‘Narratives’

On the most charitable view, David Cameron embraced the ‘Big Society’ slogan because he genuinely believed that it encapsulated a policy programme best suited to Britain's problems at the latter end of the New Labour years – and because his sincerity was seconded by key members of his entourage, notably Hilton. As we have seen, the approach he suggested had been given public support by several senior Conservatives since the fall of Thatcher, giving Cameron good reason to suppose that the initiative would be well received by his own side. His optimism was presumably reinforced by tactical considerations; the party had lacked a plausible ‘narrative’ to help it fight general elections since 1997, and the ‘Big Society’ could be presented as a unifying theme, which was at least as promising on paper as Tony Blair's ill-defined ‘Third Way’ had been for Labour in Opposition.

However, general elections, like football matches, are not contested on paper. There are several explanations for the mixed fortunes of Cameron's ‘Big Society’ as a political platform. The first relates to the most sophisticated of his audiences – MPs and commentators from a variety of ideological camps. Critics from the left were always likely to discern, beneath Cameron's relatively positive words about the state in its ‘proper’ sphere, an attack on tax-funded provision across the board, leaving ample scope for profit-seekers to offer (inferior) services to the public. It can be argued that the force of this argument was enhanced by circumstances – that is, it would not have seemed so plausible before the onset of economic recession, when Cameron could have evoked ‘the Big Society’ while promising to match Labour's spending pledges. However, Cameron's most explicit statements on the subject were delivered after the implications of the economic crisis had become apparent, laying the Conservative leader open to charges of a ‘hidden agenda’ of privatisation.

In short, the economic crisis helped to persuade Cameron's Labour opponents that the idea of a ‘Big Society’ possessed a coherence that continued to escape his own party members – that is, it was nothing more than a way of plugging gaps in public provision, which he had always (although secretly at first) intended to gouge through cuts in public spending. On this view, ‘the Big Society’ was just part of Cameron's attempt to promote Thatcherism ‘in a more palatable form for the post-Thatcherite 2010s’ (Kerr et al, 2011, p. 198; see also Byrne et al, 2012, p. 25).

If the left's analysis had been well founded, the Thatcherite wing of the Conservative Party might have been expected fully to support their leader in his attempt to hoodwink the electorate. As it was, their scornful response is the best evidence that Cameron was in earnest, and reflected widespread frustration that the Party leadership focused on the ‘Big Society’ rather than the populist ‘Tebbit trinity’ of tax cuts, immigration and the EU. Indeed, one suspects that the Conservative Right would not have been enthusiastic about any campaign theme or slogan promulgated by David Cameron. In their eyes he was a more dangerous version of John Major – someone who lacked Thatcher's crusading zeal, and was even prepared to elaborate a thoughtful defence of (limited) activity by the hated state.

Thus, Cameron's ‘Big Society’ failed to emulate Blair's ‘Third Way’ as an exercise in ‘triangulation’. Instead, it proved to be a case of the ‘triangulator’ being comprehensively ‘triangulated’, thanks to unpredictable circumstances. Navigating a middle course between ‘Thatcherism’ and ‘Old Labour’ was a fruitful electoral strategy for Blair up to 2005, because his Conservative opponents were discredited and critics within his own party were prepared to muffle their misgivings in the interests of unity. By 2010 ‘New’ Labour had limited scope for launching an ideological counter-offensive against a ‘modernised’ Conservative Party, but this was hardly helpful to the fortunes of Cameron's ‘Big Society’, as more combustible Conservative politicians and commentators who had exercised considerable restraint during the Blair–Brown years could now vent their accumulated anger against the leader who was apparently less than full-hearted in his commitment to Thatcherism.

Unlike representatives of ‘Old Labour’ in the years before 1997, the Thatcherites could also depend on several commentators in widely read newspapers to rehearse their arguments; and whatever their impact on the voters, these individuals certainly provided an impetus to Cameron's detractors at all levels within the Conservative Party.

At the elite level, then, the reception of the ‘Big Society’ was always likely to be mixed, because between 2005 and 2010 the self-anointed ‘heir to Blair’ lacked the tactical advantages, which his role-model had enjoyed in the heyday of ‘New’ Labour. Viewed from this perspective, the fact that Cameron persevered with his attempts to build the ‘Big Society’ idea into an overarching ‘narrative’ for the 2010 election campaign testifies to the curious tendency of politicians to re-fight previous contests, rather than focusing on the battle before them. In the case of the ‘Big Society’, the damage inflicted by Cameron's ideological opponents both on the left and the right was always likely to be compounded by the objections of observers without an obvious axe to grind. Such people were likely to find ‘the Big Society’ unconvincing because it was based on a view of human motivation, which could not be reconciled with the implicit message of other Conservative policies (Smith, 2010, p. 830). The grimly materialistic and self-interested individual envisaged in much of Thatcher's rhetoric was still a primary target for Conservative electoral strategists in 2010, yet such a person (if he or she really existed) was unlikely to be moved by appeals to the altruistic volunteering spirit and philanthropy, as the evidence in the various opinion polls cited in this article suggests.

A more serious objection arises from the Conservative penchant for referring to ‘Broken Britain’ before and during the campaign. Even if the Conservatives had finally accepted that one could speak of a British ‘society’, how could something ‘Broken’ suddenly become ‘Big’? The problem, among those who appraised Cameron's expressed beliefs from a well-informed but unprejudiced perspective, was accentuated by the adoption of Phillip Blond as a kind of ‘court philosopher’. If Blond was right, successive governments since 1945 – including the Thatcher-Major administrations – had inflicted serious damage on British society. Yet if governments can really damage social attitudes in the way that Blond suggested, then it followed that the genuine voluntaristic spirit, untainted by misguided state interventions of one kind or another, was likely to be rare to the point of extinction among Britons who were below pensionable age by the time of the 2010 general election. Either that, or Blond's analysis was over-schematic, and governmental policies of left and right had exercised a minimal impact on the outlook of the British people. In that case, there was no need for a Cameron-led government to launch such an impassioned appeal to the voluntaristic spirit, which would have wrought its magical effect on society, regardless of what anyone had said on the subject.

If Blond's academic analysis left serious questions unresolved, it was much more difficult for a politician in Cameron's position to translate it into rhetoric that might persuade the uncommitted while appeasing his own Thatcherite wing. In practice, he glossed over Thatcherism's contribution to Britain's woes, implying that Labour had somehow simultaneously promoted feckless individualism and excessive reliance on the state. Perhaps Cameron could not have avoided this narrowly partisan presentation of his case, but in doing so, he made it less likely that impartial observers would accept it.

Misgivings among the political and intellectual elite, whether well-founded or not, are unlikely to prove fatal to the prospects of any political programme. After all, Blair's ‘Third Way’ was vulnerable even to cursory analysis; yet it did not prevent him leading New Labour to three convincing election victories. We have argued that the ‘Big Society’ should have been a more effective concept for the Conservatives than the ‘Third Way’ ever was for New Labour, and in the long term it still offers a promising basis for a post-Thatcher Conservative Party when (or if) Britain ever returns to something like normality. However, in 2010 circumstances were far from being ‘normal’. Indeed, before the 2010 general election, it was variously said that this might be a good contest for a party to lose, and whatever the future fortunes of that great survivor, the Conservative Party qua institution, David Cameron himself might have been well served by a narrow defeat.

The first reason to take this view is the tendency of the public, in repeated opinion polls, to express cautious approval of Cameron as an individual, while continuing to mistrust the Conservative Party itself. Whether justified or not, since the 1992 general election, the public had developed an ingrained dislike for the Conservative Party, to the extent that attempts to ‘decontaminate the brand’ had to go far beyond electioneering slogans. For a variety of reasons – most notably a tendency to think that the public had rejected John Major as an individual, rather than ‘Thatcherite’ ideas – most Conservative activists failed to grasp this point, even after the 2005 general election. By 2010, though, Labour's misadventures in office had been serious enough to persuade many Britons to withdraw their support from the government, even if this meant giving the Conservatives another chance.

In short, in the elections of 2001 and 2005, the Conservatives would certainly have fared better if they had found a viable ‘narrative’ with which to oppose New Labour. But in the very different context of 2010, the promulgation of such a narrative, however persuasive in the abstract, was likely to distract voters from making a choice, which they were beginning to opt for owing to other (largely negative) reasons.

Peter Oborne has linked the idea of political ‘narratives’ to postmodernism and the rise of ‘New’ Labour; his argument implies that anyone who seeks to construct a narrative on behalf of a political party is guilty of trying to enforce their own (distorted) version of the truth (Oborne, 2005, pp. 140–146). But even if the word ‘narrative’ might seem alien and offensive to observers like Oborne, the phenomenon it denotes was familiar to observers of British electoral politics before the advent of New Labour. It would be wrong to conclude, on the grounds of terminological purism, that the Conservatives would have been better served in the circumstances of 2010 if they had renounced any attempt to develop a ‘narrative’, and instead just sat back to watch the public ejecting a government that had forfeited its respect.

The Conservatives did need to demonstrate that they had moved on from Thatcherism, and, as we have seen, Cameron's ideas provided a plausible way forward, as a kind of ‘triangulation’ between Thatcherite ‘laissez-faire’ and New Labour's alleged ‘statism’. But such a programme, forged in the full knowledge that many people (still) regarded the Conservatives as ‘the nasty party’, had to be promulgated in a way that minimised the chances of misinterpretation; and, as we have seen, this proved to be beyond the capacities of Cameron and his advisors. Persevering with the concept of the ‘Big Society’ after economic circumstances had changed in a way that increased the potential for misunderstanding was courageous but ultimately self-defeating. Another requirement was to encapsulate the idea in an effective form of words; and in this respect ‘the Big Society’ must be accounted a lamentable and avoidable failure.

A similar slogan had been adopted by Lyndon Johnson before the 1964 US Presidential election; but this was only a part (rather than the centre-piece) of Lyndon Johnson's triumphant campaign strategy, and, more importantly, he had spoken of the Great rather than the Big Society. This reflected the fact that the United States was the world's economic powerhouse in 1964, and many of its citizens had begun to look beyond material concerns to ‘quality of life’ issues (Unger, 1996).

Although David Cameron also showed signs of sharing this ‘post-materialist’ perspective before the 2010 general election by focusing on the environment and ‘well-being’, this line of argument barely featured in the campaign. Instead, the ‘Big Society’ was focused on the local rather than the global. For good reasons the British electorate had none of the confidence of the (pre-Vietnam) United States. A vision of a ‘Great Society’ was therefore off the agenda, but the substitution of the word ‘Big’ did no favours to the political prospects of Cameron, his party or his programme for government. To well-informed observers it could only evoke memories of Tony Blair's ill-starred ‘Big Conversation’, which was launched in November 2003 and quickly disappeared without a trace. For politicians, ‘Big’ might be just about adequate, when other things are going their way; but under no circumstances can it be beautiful. ‘We’re all in this together’ – a phrase that Cameron had used as early as his campaign for the party leadership in 2005 – would have been much more effective than the ‘Big Society’ as a slogan for the 2010 general election. It certainly would have been helpful to Gordon Brown, if he had thought of it first. But in practice, even ‘We’re all in this together’ was always likely to rebound in a period when any government was sure to be faced with difficult choices that could never be calculated to fall with equal severity on members of a multi-faceted society.

Thus, when properly digested, the lesson of ‘the Big Society’ seems to be that the search for a ‘narrative’ can do little harm to a party that is fairly certain of electoral defeat. But if the party has a realistic chance of winning, it should only try to develop such an overarching theme if the ideas naturally arise from a generally agreed policy programme, and are congruent with the circumstances in which the election will be fought. The belief that a narrative is necessary regardless of such considerations runs the risk of transforming an uncomplicated victory into a defeat – or saddling a party with additional distractions should it win office without an adequate majority.

Notes

‘Nudge economics’ briefly acquired some prominence, following the publication of a book entitled Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Written by two American economists, Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein (2008), Nudge explains how both individual and social behaviour could be improved through incentives and subtly steering people towards socially responsible choices, rather than relying on prescriptive measures imposed top-down by the State.

References

Ashcroft, M. (2010) Minority Verdict: The Conservative Party, the Voters and the 2010 Election. London: Biteback.

Bishop, M. and Green, M. (2011) The Road from Ruin: A New Capitalism for a Big Society. London: A. & C. Black.

Blond, P. (2009a) The Civic State: Re-moralise the Market, Re-localise the Economy and Re-capitalise the Poor. London: ResPublica.

Blond, P. (2009b) Red Tory. In: J. Cruddas and J. Rutherford (eds.) Is the Future Conservative? London: Compass/Soundings/Lawrence and Wishart.

Blond, P. (2009c) Rise of the red Tories. Prospect 28 February.

Brown, A. and Blatchford, K. (2011) The big society. In: A. Paun (ed.) One Year On: The First Year of the Coalition Government. London: Institute for Government.

Bryant, A. (1929) The Spirit of Conservatism. London: Methuen.

Burke, E. (1790/1986) Reflections on the Revolution in France. London: Penguin Classics, (originally published in 1790).

Byrne, C., Foster, E. and Kerr, P. (2012) Understanding conservative modernisation. In: T. Heppell and D. Seawright (eds.) Cameron and the Conservatives. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cameron, D. (2009) Speech: The big society. 10 November, http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2009/11/David_Cameron_The_Big_Society.aspx.

Cameron, D. (2010) Speech: Our big society plan. 31 March, http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2010/03/David_Cameron_Our_Big_Society_plan.aspx.

Cecil, L.H. (1912) Conservatism. Thornton Butterworth.

Conservative Home. (2010) Falling short: The key factors that contributed to the Conservative Party’s failure to win a parliamentary majority, http://conservativehome.blogs.com/files/electionreviewlee.pdf.

Conservative Party. (2006) Built to Last: The Aims and Values of the Conservative Party. London: Conservative Party.

Conservative Party. (2010) Invitation to Join the Government of Britain: The Conservative Manifesto 2010. London: Conservative Party.

Coote, A. (2010) Cutting it: The ‘Big Society’ and the New Austerity. London: The New Economics Foundation.

Davey, E. (2004) Liberalism and localism. In: P. Marshall and D. Laws (eds.) The Orange Book: Reclaiming Liberalism. London: Profile.

Dorey, P. (2010) Faltering before the finishing line: The Conservative Party's performance in the 2010 general election. British Politics 5 (4): 402–435.

Dorey, P., Garnett, M. and Denham, A. (2011) From Crisis to Coalition: The Conservative Party, 1997–2010. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Evans, K. (2011) ‘Big Society’ in the UK: A policy review. Children & Society 25 (2): 164–171.

Garnett, M. and Hickson, K. (2009) Conservative Thinkers. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Gilmour, I. (1992) Dancing with Dogma: Britain under Thatcherism. London: Simon and Schuster.

Gray, J. (1995) Enlightenment's Wake: Politics and Culture at the Close of the Modern Age. London: Routledge.

Gray, J. (1997) The undoing of conservatism. In: J. Gray and D. Willetts (eds.) Is Conservatism Dead? London: Profile Books/Social Market Foundation.

Green, D. (2003) More than Markets. London: Tory Reform Group.

Hailsham, L. (1978) The Dilemma of Democracy. London: Collins.

Hayek, F. (1976) Law, Legislation and Liberty, vol. 2: The Mirage of Social Justice. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hayek, F. (1988) The weasel word ‘social’. In: R. Scruton (ed.) Conservative Thoughts: Essays from ‘The Salisbury Review’. London: Claridge, pp. 49–54.

Helm, T. and Asthana, A. (2010) David Cameron faces Tory party anger. The Observer 8 May.

Huhne, C. (2007) The case for localism: The liberal narrative. In: D. Brack, R.S. Grayson and D. Howarth (eds.) Reinventing the State: Social Liberalism for the 21st Century. London: Politico's.

Hurd, D. (1988) Citizenship in the Tory democracy. New Statesman 29 April.

Hurd, D. (1989) Freedom will flourish where citizens accept responsibilities. The Independent 7 September.

Hurd, D. (2003) Memoirs. London: Little, Brown.

Hurd, D. (2007) Robert Peel: A biography. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Independent on Sunday. (2011) Battle of the Big Society: Tories go on the offensive. 13 February.

Keay, D. (1987) Interview with Margaret Thacther. Woman's Own 31 October.

Kerr, P., Byrne, C. and Foster, E. (2011) Theorising Cameronism. Political Studies Review 9 (2): 193–207.

Letwin, O. (2003) The Neighbourly Society: Collected Speeches 2001–2003. London: Centre for Policy Studies.

Letwin, O. (2009) From economic revolution to social revolution. Alan Finlayson interviews Oliver Letwin MP, In: J. Cruddas and J. Rutherford (eds.) Is the Future Conservative? London: Compass/Soundings/Lawrence and Wishart.

Long, C. (2009) Phillip Blond: The red under Cameron's bed. The Sunday Times – News Review 18 October.

Maude, A. (1969) The Common Problem: A Policy for the Future. London: Constable.

McVeigh, T. (2010) Big society: Power to the people, Cameron style. The Observer 25 July.

Montgomerie, T. (2011) Top 10 mistakes of David Cameron. The Daily Telegraph 16 July.

Mount, F. (1993) Clubbing Together: The Revival of the Voluntary Principle. London: W.H. Smith Contemporary Publications.

Mount, F. (2009) Cold Cream: My Early Life and Other Mistakes. London: Bloomsbury.

Norman, J. (2010) The Big Society: The Anatomy of the New Politics. Buckingham, UK: Buckingham University Press.

Norman, J. (2011) Stealing the Big Society. The Guardian 9 February.

Oakeshott, I. (2010) Ashcroft hits out at Tories’ election failures. The Sunday Times 8 August.

Oborne, P. (2005) The Rise of Political Lying. London: Free Press.

Scholefield, A. and Frost, G. (2011) Too ‘Nice’ To Be Tories? How the Modernisers Have Damaged the Conservative Party. London: Social Affairs Unit.

Smith, M.J. (2010) From big government to big society: Changing the state-society balance. Parliamentary Affairs 63 (4): 814–833.

Sunday Mirror. (2011) David Cameron’s Big Society: Voters believe Tory ‘vision’ just a gimmick to cover spending outs. 13 February.

Sylvester, R. (2011) A Facebook policy met by baffled faces. The Times 15 February.

Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Unger, I. (1996) The Best of Intentions: The Triumph and Failure of the Great Society under Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon. New York: Doubleday.

Watt, N. (2010) There's No Such Thing as ‘Big Society’, Senior Tories Tell Cameron. The Guardian 20 April.

Willetts, D. (1992) Modern Conservatism. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.