Abstract

The comparative political economy of developed countries has often neglected the growing interest in producing well-being indicators that go beyond GDP. This was largely due to lack of reliable and comparable data. In spite of this, Osberg and Sharpe have recently provided a time-series cross-section data set of the Index of Economic Well-Being (IEWB) for selected OECD countries. Accordingly, this article tries to plug the current gap between the comparative political economy and well-being literature by presenting an empirical study about the impact of partisanship and state intervention on the IEWB and its four domains (that is, consumption flows, stocks of wealth, economic equality, economic security). A main lesson can be drawn from the econometric analysis: left cabinets and their favorite policies increase stocks of wealth, economic equality and economic security, rather than consumption flows. This means that leftist governments do not promote the current prosperity of a typical citizen but the future and widespread well-being of most population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although HDI is one of the few indexes that are regularly compiled and widely disseminated by international organizations to allow systematic cross-country comparisons, it appears to be useful only for comparisons between developing economies (Afsa et al, 2008), and not really relevant for capturing differences among developed countries.

Three adjustments have been made to these components. First, as economies of scale exist in private household consumption, private consumer expenditure is adjusted for changes in family size. Second, an adjustment is made to consumption flows to account for the large international differences in growth rates and levels of annual hours worked. Third, an adjustment for the positive impact of increased life expectancy on well-being is made by adjusting total consumption flows by the percentage increase in life expectancy (Osberg and Sharpe, 2009).

One adjustment is made to the sum of these components: to account for the social costs of environmental degradation, the estimated annual cost of greenhouse gas emissions is subtracted (Osberg and Sharpe, 2009).

The Gini coefficient is used here to measure inequality among values of income distribution. As is well known, it is equal to zero when equality is perfect and everyone has an exactly equal income. By contrast, it corresponds to one when inequality is maximal and only one person has all the income. Poverty intensity is the product of the poverty rate and the poverty gap. The poverty rate and gap, as well as Gini coefficient, are based on family after-tax equivalent income. The poverty rate is the proportion of persons whose income is below the poverty line (the poverty line corresponds to 50 per cent of the median family income). The poverty gap is the average per cent difference between the poverty line and the incomes of those whose incomes fall below it (Osberg and Sharpe, 2009).

The risk imposed by unemployment is determined by two variables: the unemployment rate and the proportion of earnings that are replaced by unemployment benefits. Each of these measures is scaled and then summed with weights of 0.8 and 0.2, respectively. The risk imposed by illness corresponds to the private Medical care expenses as a percentage of disposable income. The risk of single-parent poverty consists of three variables: divorce rate, poverty rate for lone female-headed families and poverty gap for these families. The risk of poverty in old age is proxied by the poverty intensity experienced by the households headed by a person aged 65 years or over (Osberg and Sharpe, 2009).

Although the data set developed by Osberg and Sharpe (2009) includes data from 14 developed countries observed over the period 1980–2007, I have limited my analysis to the 13 countries observed over the period 1980–2000. This is because the sources I have used for the main independent variables do not allow further analysis (see below).

In order to standardize the ranges of different variables, a linear scaling technique is applied to the IEWB and its four domains (Osberg and Sharpe, 2009).

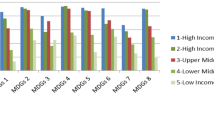

Scatter plots, built by plotting the two other main independent variables along the horizontal axis, are given in the Appendix (see Figures A1 to A5).

For an analogous strategy of analysis, see Huber et al (1993, p. 733). The fixed effect specification is also avoided because it allows the effects to be captured with respect to the intra-unit variation only. This is because country dummies inclusion replaces the dependent and independent variables with their unit centered deviations, removing any of the average unit-to-unit variation from the analysis (Greene, 2003).

The regressions are Prais–Winsten estimates – panel-corrected standard errors and corrections for first-order auto-regressiveness.

The spurious correlation, deriving from high temporal persistence, may be also addressed by first-difference analysis (Kittel and Winner, 2005). However, I have avoided such a solution because it is suitable to capture the short-run dynamics rather that long-term relationships. Differencing data is thus substantively inappropriate.

In order to check the robustness of the main variables of interest, several specifications are performed including different combinations of controls. Not all the results of repeated cross-section analysis are reported here, but are available upon request.

A similar exercise has been carried out by Garrett (1998).

Only the results for the cross-section regressions are reported here, including left-wing cabinets as the main independent variables. Results obtained by using public receipts and state generosity are available upon request.

References

Afsa, C. et al (2008) Survey of existing approaches to measuring socio-economic progress. Background paper for the first meeting of the CMEPSP.

Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1996) Income distribution, political instability and investment. European Economic Review 40 (6): 1203–1228.

Alvarez, R.M., Garrett, G. and Lange, P. (1991) Government partisanship, labor organization, and macroeconomic performance. American Political Science Review 85 (2): 539–556.

Beck, N. and Katz, J. (2011) Modeling dynamics in time-series-cross-section political economy data. Annual Review of Political Science 14: 331–352.

Blanchard, O.J. (2008) Crowding out. In: S.N. Durlauf and L.E. Blime (eds.) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd edn. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Boix, C. (1997) Political parties and the supply side of the economy: The provision of physical and human capital in advanced economies. American Journal of Political Science 41 (3): 814–845.

Brady, D. (2003) The politics of poverty: Left political institutions, the welfare state, and poverty. Social Forces 82 (2): 557–588.

Daly, H. and Cobb, J. (1989) For the Common Good. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2007) Multiple regression in small-N comparisons capitalisms compared. Comparative Social Research 24: 335–342.

Estes, R., Levy, M., Srebotnja, T. and de Shrebinin, A. (2005) 2005 Environmental Sustainability Index: Benchmarking National Environmental Stewardship. New Haven, CN: Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy.

Garrett, G. (1998) Partisan Politics in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giavazzi, F. and Pagano, M. (1990) Can severe fiscal contractions be expansionary? Tales of two small European countries. NBER Macroeconomic Annual 5: 75–110.

Giavazzi, F. and Pagano, M. (1996) Non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy changes: International evidence and the Swedish experience. Swedish Economic Policy Review 3 (1): 67–103.

Greene, W. (2003) Econometric Analysis, 5th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hibbs, D.A. (1977) Political parties and macro-economic policy. American Political Science Review 71 (4): 1467–1487.

Hibbs, D.A. (1987) The American Political Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Huber, E. and Stephens, J.D. (2001) Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Huber, E., Ragin, C. and Stephens, J.D. (1993) Social democracy, cdemocracy, constitutional structure, and the welfare state. American Journal of Sociology 99 (3): 711–749.

Huber, E., Ragin, C., Stephens, J.D., Brady, D. and Beckfield, J. (2004) Comparative Welfare States Data Set. Northwestern University, University of North Carolina, Duke University, and Indiana University, http://www.unc.edu/~jdsteph/.

Iversen, T. and Cusack, T. (2000) The causes of welfare state expansion. De-industrialization or globalization? World Politics 52 (3): 313–349.

Jonsson, K. (2004) Fiscal Policy Regimes and Household Consumption. Sweden: Department of Economics, Lund University. Working Papers no. 2004/12.

Kenworthy, L. (1999) Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment. Social Forces 77 (3): 1119–1139.

Kenworthy, L. (2004) Egalitarian Capitalism: Jobs, Incomes and Growth in Affluent Countries. New York: Russell Sage.

Kittel, B. (1999) Sense and sensitivity in pooled analysis in political data. European Journal of Political Research 35 (2): 225–253.

Kittel, B. and Winner, H. (2005) How reliable is pooled analysis in political economy? The globalization-welfare state nexus revisited. European Journal of Political Research 44 (2): 269–293.

Lipset, S.M. (1983) Political Man. Garden City, NY: Anchor.

Moller, S., Huber, E., Stephens, J.D., Bradley, D. and Nielsen, F. (2003) Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies. American Sociological Review 68 (1): 22–51.

Nordhaus, W. and Tobin, J. (1972) Is Growth Obsolete? New York: Columbia University Press.

Osberg, L. and Sharpe, A. (1998) An Index of Economic Well-being for Canada. Research Report, Applied Research Branch, Human Resources Development Canada, December.

Osberg, L. and Sharpe, A. (2002) An index of economic well-being for selected countries. Review of Income and Wealth 48 (3): 291–316.

Osberg, L. and Sharpe, A. (2005) How should we measure the ‘economic’ aspects of well-being? Review of Income and Wealth 51 (2): 311–336.

Osberg, L. and Sharpe, A. (2009) New Estimates of the Index of Economic Well-being for Selected OECD Countries. CSLS Research Report 2009–11.

Pacek, A. and Radcliff, B. (2008) Assessing the welfare state: The politics of happiness. Perspectives on Politics 6: 267–277.

Pesaran, M.H. and Smith, R.P. (1995) Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 68 (1): 79–113.

Pinto, P.M. and Pinto, S.M. (2008) Partisanship, sectoral allocation of foreign direct investment, and imperfect capital mobility. Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Conference of the International Political Economy Society;14–15 November, Philadelphia, PA.

Radcliff, B. (2001) Politics, markets, and life satisfaction: The political economy of human happiness. American Political Science Review 95 (4): 939–952.

Radcliff, B. (2005) Class organization and subjective well-being in the industrial democracies. Social Forces 84 (1): 512–530.

Scruggs, L. (2004) Welfare State Entitlements Data Set: A Comparative Institutional Analysis of Eighteen Welfare States. Version 1.0. University of Connecticut, http://sp.uconn.edu/~scruggs/wp.htm.

Scruggs, L. and Allan, J.P. (2006a) Welfare state decommodification in eighteen OECD countries: A replication and revision. European Journal of Social Policy 16 (1): 55–72.

Scruggs, L. and Allan, J.P. (2006b) The material consequences of welfare states benefit generosity and absolute poverty in 16 OECD countries. Comparative Political Studies 39 (7): 880–904.

Veenhoven, R. and Kalmijn, W.M. (2005) Inequality-adjusted happiness in nations. Journal of Happiness Studies 6: 421–455.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this article was presented at the seminar held at the Department of Social and Political Studies of the University of Milan, Italy. To this regard, I am particularly grateful to the comments by Ferruccio Biolcati-Rinaldi, Giovanni Carbone, Fabio Franchino and the other participants. Furthermore, I would like to thank Andrew Sharpe for the helpful discussions on the various aspects of this article. Finally, my thanks go to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions to improve the quality of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Podestà, F. Partisanship, state intervention and economic well-being in 13 developed countries, 1980–2000. Comp Eur Polit 12, 76–100 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.34

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.34