Abstract

Far-right parties blame immigrants for unemployment. We test the effects of the unemployment rate on public receptivity to this rhetoric. The dependent variable is anti-immigrant sentiment. The key independent variables are the presence of a far-right party and the level of unemployment. Building from influential elite-centered theories of public opinion, the central hypothesis is that a high unemployment rate predisposes citizens to accept the anti-immigrant rhetoric of far-right parties, and a low unemployment rate predisposes citizens to reject this rhetoric. The findings from cross-sectional, cross-time and cross-level analyses are consistent with this hypothesis. It is neither the unemployment rate nor the presence of a far-right party that appears to drive anti-immigrant sentiment; rather, it is the interaction between the two.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Legislative elections are counted only during presidential election years in the United States, they are counted only since 1991 in Portugal, and the two elections in Ireland in 1982 are counted as a single election. Our discussion here, and only here, takes into consideration the observation that many far-right parties did not begin as far-right parties. Thus, the Freedom Party (FPO) in Austria is not counted as a far-right party before the 1990 election (Betz, 1994; Riedlsperger, 1998). Similarly, the Progress Parties (FrP) in Denmark and Norway are not counted as far-right parties until the 1987 and 1989 elections, respectively (Svåsand, 1998; Andersen and Bjørklund, 2002). And the Swiss People's Party (SVP) is not considered a far-right party before the 1995 election (McGann and Kitschelt, 2005; Skenderovic, 2007). These transitions correspond in all cases to the adoption by these parties of an anti-immigration agenda that they had not previously promoted. In the ensuing analyses, however, we treat as far-right parties all political parties that eventually became far-right parties, regardless of the time-period under consideration. And we treat as ‘far-right countries’ all countries that have, or eventually acquired, a far-right party, regardless of the time-period under consideration. This decision allows us to avoid making consequential qualitative decisions about the precise moment at which a country acquired a far-right party. We prefer, instead, to assess the consequences of these kinds of cross-time changes as independent variables in our regression models.

These data nonetheless include stocks of foreigners, rather than proportion of foreign-born, for Germany.

More specifically, we code the percentage of the non-Anglo American and non-European immigrants as the percentage of the total national population in each country that was born outside of the European Economic Area, Switzerland, Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. The data are provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (stats.oecd.org), and were derived from national censuses in and around the year 2000.

‘Level of education’ categories are used in lieu of ‘age completed education’ for New Zealand. These educational categories range from less than high school (1) to completed university (7). For all other countries, education is measured as ‘age completed’, ranging from less than 12 years of age (1) at the low end, to more than 20 years of age (10) at the high end.

We impute missing values using STATA's MI IMPUTE command. We estimate the missing values for individual-level variables by using the logit method for the dichotomous variables (anti-immigrant sentiment and gender), the logit method for ordinal variables (political interest and education), and the regress method for age. Each of the imputation models includes all of the individual-level variables in the final regression model, as well as a series of dichotomous country variables. We do not include the contextual variables, which have no missing values, to estimate imputed values for missing individual-level observations. The final models use 10 imputations for each individual-level variable, but the graphics are constructed using only the first set of these imputations. There are 710 imputed values for the dependent variable, anti-immigrant, and there are 576 imputed values for age, 123 for female, 6129 for education, and, since the question was first asked in 1989, 592 imputed observations for political interest.

We do not have enough observations on our country-level variables to estimate random slopes for our key variables of interest.

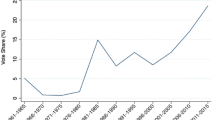

Indeed, a higher unemployment rate is associated with lower levels of anti-immigrant sentiment in these countries for much of the past 30 years. More recently, however, this effect has dissipated.

References

Andersen, J.G. and Bjørklund, T. (2002) Anti-immigration parties in Denmark and Norway: The progress parties and the Danish people's party. In: M. Schain, A. Zolberg and P. Hossay (eds.) Shadows over Europe: The Development and Impact of the Extreme Right in Western Europe. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 107–136.

Anderson, C.J. (1996) Economics, politics, and foreigners: Populist party support in Denmark and Norway. Electoral Studies 15 (4): 497–511.

Benoit, K. and Laver, M. (2006) Party Policy in Modern Democracies. New York, NY: Routledge.

Betz, H.-G. (1994) Radical Right-wing Populism in Western Europe. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Blumer, H. (1958) Race prejudice as a sense of group threat. Pacific Sociological Review 1 (1): 3–7.

Carter, E. (2005) The Extreme Right in Western Europe: Success or Failure? Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Converse, P.E. (1964) The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In: D.E. Apter (ed.) Ideology and Discontent. New York, NY: Free Press, pp. 206–261.

Cutts, D., Ford, R. and Goodwin, M. (2011) Anti-immigrant, politically disaffected or still racist after all? Examining the attitudinal drivers of extreme right support in Britain in the 2009 European elections. European Journal of Political Research 50 (3): 418–440.

Druckman, J.N. (2001) On the limits of framing effects: Who can frame? The Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1041–1066.

Druckman, J.N. (2004) Political preference formation: Competition, deliberation, and the (ir)relevance of framing effects. American Political Science Review 98 (4): 671–686.

Druckman, J.N. and Nelson, K.R. (2003) Framing and deliberation: How citizens’ conversations limit elite influence. American Journal of Political Science 47 (4): 729–745.

Entman, R.M. (1993) Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

Golder, M. (2003) Explaining variation in the success of extreme right parties in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies 36 (4): 432–466.

Hainsworth, P. (2008) The Extreme Right in Western Europe. New York: Routledge.

Hamilton, R.F. (1982) Who Voted for Hitler? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hopkins, D.J. (2010) Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

Ignazi, P. (1992) The silent counter-revolution: Hypotheses on the emergence of extreme right-wing parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 22 (1): 3–34.

Immerfall, S. (1998) Conclusion. In: H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. London, UK: Macmillan Press, pp. 249–262.

Ivarsflaten, E. (2005) The vulnerable populist right parties: No economic realignment fuelling their electoral success. European Journal of Political Research 44 (3): 465–492.

Ivarsflaten, E. (2008) What unites right-wing populists in Western Europe? Re-examining grievance mobilization models in seven successful cases. Comparative Political Studies 41 (1): 3–23.

Iyengar, S. and Kinder, D.R. (1987) News That Matters: Television and American Opinion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Jackman, R.W. and Volpert, K. (1996) Conditions favoring parties of the extreme right in Western Europe. British Journal of Political Science 26 (4): 501–521.

Jacobs, L.R. and Shapiro, R.Y. (2000) Politicians Don’t Pander: Political Manipulation and the Loss of Democratic Responsiveness. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Jacoby, W.G. (2000) Issue framing and public opinion on government spending. American Journal of Political Science 44 (4): 750–767.

Johnson, C. (1998) Pauline Hanson and one nation. In: H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, pp. 211–218.

Kitschelt, H. and McGann, A.J. (1995) The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Knigge, P. (1998) The ecological correlates of right-wing extremism in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 34 (2): 249–279.

Lemaitre, G. (2005) The comparability of international migration statistics: Problems and prospects. OECD Statistics Brief, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/4/41/35082073.pdf, accessed 4 March 2010.

Lemaitre, G. and Thoreau, C. (2006) Estimating the foreign-born population on a current basis. OECD, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/18/41/37835877.pdf, accessed 4 March 2010.

Lubbers, M. (2004) Expert Judgment Survey of Western-European Political Parties 2000. Rev. ed. Machine Readable Dataset. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: NWO, Department of Sociology, University of Nijmegen, Data archived and distributed by the Netherlands Institute for Scientific Information Services (Steinmetz Archives).

Lubbers, M., Gusberts, M. and Scheepers, P. (2002) Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 41 (3): 345–378.

Lubbers, M. and Scheepers, P. (2000) Individual and contextual characteristics of the German extreme right-wing vote in the 1990s: A test of complementary theories. European Journal of Political Research 38 (1): 63–94.

Lubbers, M. and Scheepers, P. (2005) A puzzling effect of unemployment: A reply to Dülmer and Klein. European Journal of Political Research 44 (2): 265–268.

Lucassen, G. and Lubbers, M. (2012) Who fears what? Explaining far-right wing preference in Europe by distinguishing perceived cultural and economic ethnic threats. Comparative Political Studies 45 (5): 547–574.

McCloskey, H. and Zaller, J. (1984) The American Ethos: Public Attitudes Toward Capitalism and Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McGann, A.J. and Kitschelt, H. (2005) The radical right in the Alps: Evolution of support for the Swiss SVP and the Austrian FPO. Party Politics 11 (2): 147–171.

McLaren, L.M. (2003) Anti-immigrant prejudice in Europe: Contact, threat perception, and preferences for the exclusion of migrants. Social Forces 81 (3): 909–936.

Meguid, B.M. (2008) Party Competition Between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Nunn, C.Z., Crockett, H.J. and Williams, J.A. (1978) Tolerance for Nonconformity. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2009) Labor Force Survey Dataset: Standardized Unemployment Rate, www.oecd.org/statistics, accessed 2 March 2009.

Pettigrew, T.F. (1998) Reactions toward the new minorities of Western Europe. Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 77–103.

Quillian, L. (1995) Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review 60 (4): 586–611.

Rabe-Hesketh, S. and Skrondal, A. (2008) Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, 2nd edn. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Riedlsperger, M. (1998) The freedom party of Austria: From protest to radical-right populism. In: H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, pp. 27–44.

Rink, N., Phalet, K. and Swyngedouw, M. (2009) The effects of immigrant population size, unemployment, and individual characteristics on voting for the Vlaams Blok in Flanders 1991–1999. European Sociological Review 25 (4): 411–424.

Rydgren, J. (2005) Is extreme right-wing populism contagious? Explaining the emergence of a new party family. European Journal of Political Research 44 (3): 413–437.

Rydgren, J. (2008) Immigration skeptics, xenophobes, or racists? Radical right-wing voting in six West European countries. European Journal of Political Research 47 (6): 737–765.

Scheepers, P., Gijsberts, M. and Coenders, M. (2002) Ethnic exclusionism in European countries: Public opposition to civil rights for legal migrants as a response to perceived ethnic threat. European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34.

Semyonov, M., Raijman, R. and Gorodzeisky, A. (2006) The rise of anti-foreigner sentiment in European societies, 1988–2000. American Sociological Review 71 (3): 426–449.

Sides, J. and Citrin, J. (2007) European opinion about immigration: The role of identities, interests and information. British Journal of Political Science 37 (3): 477–504.

Skenderovic, D. (2007) Immigration and the radical right in Switzerland: Ideology, discourse and opportunities. Patterns of Prejudice 41 (2): 155–176.

Sniderman, P.M., Hagendoorn, L. and Prior, M. (2004) Predispositional factors and situational triggers: Exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. American Political Science Review 98 (1): 35–50.

Snijders, T.A. and Bosker, R.J. (1999) Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Svåsand, L. (1998) Scandinavian right-wing radicalism. In: H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, pp. 77–94.

Swyngedouw, M. (1998) The extreme right in Belgium: Of a non-existent front national and an omnipresent Vlaams Blok. In: H.-G. Betz and S. Immerfall (eds.) The New Politics of the Right: Neo-Populist Parties and Movements in Established Democracies. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, pp. 59–74.

Tarrow, S. (1998) Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Thränhardt, D. (1995) The political uses of xenophobia in England, France and Germany. Party Politics 1 (3): 323–345.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1981) The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211 (4481): 453–458.

Van der Brug, W. and Fennema, M. (2003) Protest or mainstream? How the European Anti-immigrant parties developed into two separate groups by 1999. European Journal of Political Research 42 (1): 55–76.

Wilkes, R., Guppy, N. and Farris, L. (2007) Right-wing parties and anti-foreigner sentiment in Europe. American Sociological Review 72 (5): 831–840.

Wilson, T.C. (2001) Americans’ views on immigration policy: Testing the role of threatened group interests. Sociological Perspectives 44 (4): 485–501.

Zaller, J.R. (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cochrane, C., Nevitte, N. Scapegoating: Unemployment, far-right parties and anti-immigrant sentiment. Comp Eur Polit 12, 1–32 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.28

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.28