Abstract

This article examines to what extent different formal conceptualizations of ideological conflict can help to explain the capacity for and speed of policy change in the European Union (EU). We compare the core and the winset, two competing concepts based on the spatial theory of voting. The empirical analysis shows that the latter concept bears a strong and systematic influence on decision making in the EU. The smaller the winset containing the outcomes that a majority of actors in the Council of the EU prefers over the status quo, the longer a decision-making process lasts and the smaller the potential for policy change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We dropped all issues with four or more missing values for member states’ ideal point positions, a missing value for the Commission position, a missing value for the EP for co-decision cases, a missing outcome value or a missing value for the status quo. This reduced the original data set by 61 issues, among which there were eight complete proposals. The sample we use has a total of 62 proposals consisting of 113 issues. For cases with four or less missing values, the values were imputed by viewing the member state’s position as indifferent to the status quo (Steunenberg and Selck, 2006, 70).

While Ganghof (2003) makes a distinction between outcome preferences, positional preferences and final preferences, we measure like most spatial models negotiation positions of veto players regarding specific policy proposals tabled by the European Commission.

The data represent different measurement levels which vary between dichotomous, ordinal and metric scales. We therefore used a mixture of dimension-reduction techniques and qualitative considerations to determine the relevant number of conflict dimensions (Zimmer et al, 2005). If the results of the principal components analysis, the correspondence analysis and a substantial examination of the content of two statistically clearly correlated issues were confirmative, we assumed that two, or sometimes three, issues could be traced back to one underlying conflict dimension. The results of these three analyses were mostly in line with each other and led to a unique number as well as a substantive ‘label’ for the aggregated dimensions in all of the 18 cases where the number of dimensions has been reduced.

Depending on the decision rule applied, the Council core is the convex hull of the ideal points of all member states in case of unanimity or the area defined by the q-dividers in the event that a qualified majority threshold is used. A q-divider is a line that connects the ideal points of two actors who are pivotal for a possible winning coalition (the lines defining the centrally located heptagon in Figure 1). Each q-divider thus separates the policies preferred by this majority coalition and those preferred by a losing minority of actors or votes. The centrally located polygon formed by all q-dividers is the set of points that are never on the ‘losing side’ of a q-divider, that is, there exists no coalition preferring a point outside the core.

The five-out-of-seven-rule roughly corresponds to the voting threshold under QMV in the EU Council of Ministers.

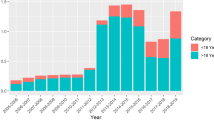

Golub (2007) argues that studies of EU decision-making speed should account for state changes in variables, as all important variables are likely to change over time as a result of, for example, EU treaty reform or enlargement, government change or new modes of actor behavior. We expect that the effects of certain of our independent variables change over time, and therefore account for time-dependent coefficients. However, it has to be acknowledged that the composition of governments might have changed because of national elections over the course of the legislative process. Given that the DEU dataset only measured the policy positions immediately after the introduction of the Commission proposal, we are not able to take state changes in the ideological composition of the Council into account (Thomson and Stokman, 2006, p. 38).

We conducted correlation and variance inflation tests and found heteroskedasticity to represent no problem.

We ran two model specifications interacting each of the non-proportional covariates with time and ln(time). Both models arrive at the same substantial findings with regard to our explanatory variables. As the fit of the model including time interactions is superior to the fit of the model using ln(time) interactions, we only present the time interaction model.

References

Berl, J.E., McKelvey, R.D., Ordeshook, P. and Winder, M.P. (1976) An experimental test of the core in a simple N-person cooperative nonsidepayment game. Journal of Conflict Resolution 20(3): 453–479.

Box-Steffensmeier, J.M. and Jones, B.S. (2004) Event History Modeling: A Guide for Social Scientists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bueno de Mesquita, B. (2002) Predicting Politics. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.

Colomer, J.M. (1999) The geometry of unanimity rule. Journal of Theoretical Politics 11(4): 543–553.

Crombez, C. (1996) Legislative procedures in the European community. British Journal of Political Science 26(2): 199–228.

Crombez, C. (1997) The Co-decision procedure in the European Union. Legislative Studies Quarterly 22(1): 97–119.

Crombez, C. (2001) The treaty of Amsterdam and the co-decision procedure. In: G. Schneider and M. Aspinwall (eds.) The Rules of Integration. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, pp. 101–122.

Crombez, C. and Hix, S. (2015) Legislative activity and gridlock in the European Union. British Journal of Political Science 45(3): 477–499.

Dobbins, M., Drüner, D. and Schneider, G. (2004) Kopenhagener Konsequenzen: Gesetzgebung in der EU vor und nach der Erweiterung. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 35(1): 51–68.

Drüner, D. (2008) Between Chaos and Sclerosis: Decision-making in the ‘Old’, the Enlarged and a Reformed European Union. Saarbrücken, Germany: VDM Verlag.

Franchino, F. (2004) Delegating powers in the European community. British Journal of Political Science 34(2): 449–476.

Franchino, F. (2007) The Powers of the Union. Delegation in the EU. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ganghof, S. (2003) Promises and pitfalls of veto player analysis. Swiss Political Science Review 9(2): 1–25.

Golub, J. (1999) In the shadow of the vote? Decision-making in the European community. International Organization 53(4): 733–764.

Golub, J. (2002) Institutional reform and decisionmaking in the European Union. In: M. Hosli and A. van Deemen (eds.) Institutional Challenges in the European Union. London: Routledge, pp. 134–154.

Golub, J. (2007) Survival analysis and European Union decision-making. European Union Politics 8(2): 155–179.

Golub, J. (2008) The study of decision-making speed in the European Union: Methods, data and theory. European Union Politics 9(1): 167–179.

Golub, J. and Steunenberg, B. (2007) How time affects EU decision-making. European Union Politics 8(4): 555–566.

Greenberg, J. (1979) Consistent majority rules over compact sets of alternatives. Econometrica 47(3): 627–636.

Hammond, T.H. and Butler, C.K. (2003) Some complex answers to the simple question ‘do institutions matter?’: Policy choice and policy change in presidential and parliamentary systems. Journal of Theoretical Politics 15(2): 145–200.

Hammond, T.H. and Miller, G.J. (1987) The core of the constitution. American Political Science Review 81(4): 1155–1174.

Humphreys, M. (2008) Existence of a multicameral core. Social Choice and Welfare 31(3): 503–520.

Klüver, H. and Sagarzazu, I. (2013) Ideological congruency and decision-making speed: The effect of partisanship across European Union institutions. European Union Politics 14(3): 388–407.

König, T. (2007) Convergence or divergence? From ever-growing to ever-slowing European legislative decision making. European Journal of Political Research 46(3): 417–444.

König, T. (2008) Analysing the process of EU legislative decision-making: To make a long story short. European Union Politics 9(1): 145–165.

König, T. and Bräuninger, T. (2004) Accession and reform of the European Union. European Union Politics 5(4): 419–439.

Lewis, J. (1998) Is the hard bargaining image of the council misleading? The committee of permanent representatives and the local election directive. Journal of Common Market Studies 36(4): 479–504.

Lewis, J. (2000) The methods of community in EU decision-making and administrative rivalry in the council’s infrastructure. Journal of European Public Policy 7(2): 261–289.

Mattila, M. (2012) Resolving controversies with DEU data. European Union Politics 13(3): 451–461.

Sandler, T. and Hartley, K. (2001) Economics of alliances: The lessons for collective action. Journal of Economic Literature 39(3): 869–896.

Schneider, G. (1995) The Limits of Self-Reform: Institution Building in the European Community. European Journal of International Relations 1(1): 59–86.

Schneider, G. and Baltz, K. (2005) Domesticated eurocrats: Bureaucratic discrection in pre-negotiations of the European Union. Acta Politica 40(1): 1–27.

Schneider, G., Steunenberg, B. and Widgrén, M. (2006) Evidence with insight: What models contribute to EU research. In: R. Thomson, F.N. Stokman, C.H. Achen and T. König (eds.) The European Union Decides. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 299–316.

Schofield, N., Grofman, B. and Feld, S.L. (1988) The core and the stability of group choice in spatial voting games. American Political Science Review 82(1): 195–211.

Schulz, H. and König, T. (2000) Institutional reform and decision-making efficiency in the European Union. American Journal of Political Science 44(4): 653–666.

Selck, T.J. (2006) Preferences and Procedures: European Union Legislative Decision-Making. New York: Springer.

Shapiro, I. (2003) Optimal deliberation? In: J.S. Fishkin and P. Laslett (eds.) Debating Deliberative Democracy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 121–137.

Sloot, T. and Verschuren, P. (1990) Decision-making speed in the European community. Journal of Common Market Studies 29(1): 75–85.

Steunenberg, B. (1994) Decision making under different institutional arrangements: Legislation by the European community. Journal of Theoretical and Institutional Economics 150(4): 642–669.

Steunenberg, B. (ed.) (2002) An even wider Union: The effects of enlargements on EU decision-making. In: Widening the European Union: The Politics of Institutional Change and Reform. London: Routledge, pp. 97–118.

Steunenberg, B. and Selck, T. (2006) Testing procedural models of EU legislative decision-making. In: R. Thomson, F.N. Stokman, C.H. Achen and T. König (eds.) The European Union Decides. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 54–84.

Thomson, R. (2011) Resolving Controversy in the European Union. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thomson, R. and Stokman, F.N. (2006) Research design: Measuring actors’ positions, saliences and capabilities’. In: R. Thomson, F.N. Stokman, C.H. Achen and T. König (eds.) The European Union Decides. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 25–53.

Thomson, R., Stokman, F.N., Achen, C.H. and König, T. (eds.) (2006) The European Union Decides. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Toshkov, D. and Rasmussen, A. (2012) Time to decide: The effect of early agreements on legislative duration in the EU. European Integration Online Papers (EIoP) 16(11): 1–20.

Tsebelis, G. (1994) The power of the European parliament as a conditional agenda setter. American Political Science Review 88(1): 128–142.

Tsebelis, G. (1997) Maastricht and the democratic deficit. Aussenwirtschaft 52(1/2): 29–56.

Tsebelis, G. (2002) Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tsebelis, G. and Yataganas, X. (2002) Veto players and decision-making in the EU after nice. Journal of Common Market Studies 40(2): 283–307.

Zimmer, C., Schneider, G. and Dobbins, M. (2005) The contested council: The conflict dimensions of an intergovernmental institution. Political Studies 53(2): 403–422.

Zubek, R. and Klüver, H. (2015) Legislative pledges and coalition government. Party Politics 21(4): 603–614.

Acknowledgements

Financial assistance by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Baden-Württemberg Graduate Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Thomas König, Frans N. Stokman and Robert Thomson for valuable comments and suggestions. Replication data will be made available on www.uni-konstanz.de/FuF/Verwiss/GSchneider/downloads/daten.htm.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drüner, D., Klüver, H., Mastenbroek, E. et al. The core or the winset? Explaining decision-making duration and policy change in the European Union. Comp Eur Polit 16, 271–289 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.26

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.26