Abstract

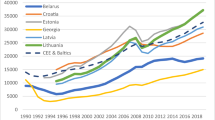

We compare and contrast the economic growth performance of Croatia and Latvia since the collapse of communism in 1991, in an attempt to understand better the extent to which the output growth differential between the two countries can be traced to increased efficiency in the use of capital and other resources (intensive growth) as opposed to sheer accumulation of capital (extensive growth). On the basis of a simple growth accounting model, we infer that advances in education at all levels, good governance, and institutional reforms have played a significant role in raising economic output and efficiency in both Croatia and Latvia. The EU perspective seems to have made a more significant contribution to growth in Latvia than in Croatia, even if Latvia's immediate post-accession boom proved unsustainable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other examples include Gylfason (2006), Barry et al. (2009), and Henry and Miller (2009). We draw heavily on Gylfason and Hochreiter (2009).

The EU perspective is a key factor today behind economic, institutional, and political developments in the Western Balkans as a whole as was the case in the Baltic countries before the joined the EU in 2004.

Croatia's real GDP contracted by 5.8% in 2009 but showed some growth in 2008.

For an excellent survey, see Havrylyshyn (2001).

Klomp and Haan (2009) report that democracy also reduces economic volatility.

Senhadji (2000) estimates aggregate production functions for 88 countries, but neither Latvia nor Croatia is included in his sample.

Neither Croatia nor Latvia is included in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, a path-breaking project intended to measure the output of education systems rather than the inputs.

The distribution of human capital across the population may be just as important as the average level of human capital, perhaps even more so, but we do not have data on the distributional aspects of education in the two countries.

Comparisons of data from the Soviet time with those of the post-Soviet period need to be taken with a grain of salt. Hence, the statement in the text has to be interpreted with care, especially if the cost of queuing, product range and quality, and so forth, is included in the GDP measure.

By the interest spread is meant the interest rate charged by banks on loans to prime customers minus the interest rate paid by commercial or similar banks for demand, time, or savings deposits.

The reason for the spike in the Latvian data on hours of work in 2005 can be traced to the jump in hours that year in fishing, transport, storage and communications, and public administration and defense (see ILO: http://laborsta.ilo.org/).

Compensation of employees consists of all payments in cash, as well as in kind (such as food and housing), to employees in return for services rendered, and government contributions to social insurance schemes such as social security and pensions that provide benefits to employees (World Development Indicators 2010).

The Copenhagen Criteria were laid down at the 1993 European Council in Copenhagen. Their fulfillment is a prerequisite for EU accession. In particular, they stipulate that ‘Membership requires that the candidate country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. Membership presupposes the candidate's ability to take on the obligations of membership including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union’. See http://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/ec/pdf/cop_en.pdf.

Note that Latvia introduced obligatory preschool of 2 years in 2002. Nonetheless, we continue to use the primary school data excluding the two preschool years. The Croatian education system adopted the Bologna system for higher education in 2005, that is, a 3-year Bachelor and a 2-year Master. Prior to 2005, 4 years were needed to complete the first university degree (diploma) (Sources: Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Latvia and Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of the Republic of Croatia).

The primary school-enrollment rates are net, and refer to the ratio of children of official school age who are enrolled in school to the population of the corresponding official school age. The secondary and tertiary rates are gross, and refer to the ratio of total enrollment, regardless of age, to the population of the age group that officially corresponds to the level of education in question (Source: World Development Indicators 2010).

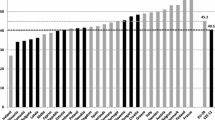

Both countries’ exposure to the world economy (in particular, the EU) was nearly equal at around 43% of goods and services as shown in Figure 7.

For Latvia an important caveat is appropriate. It is not clear how much of the TFP growth was sustainable since disproportionate activity went into the nontradable sector such as real estate and contraction. We are grateful to David Moore for pointing this out.

The official accession process for the 10 former communist countries in Europe was formally launched at the end of March 1998.

References

Acemoglu, D. and Johnson, S. 2005: Unbundling institutions. Journal of Political Economy 113 (5): 949–995.

Bakker, B.B. and Gulde, A. 2010: The credit boom in the EU new member states: Bad luck or bad policies? IMF Working paper WP 10/130, Washington, D.C.

Bardhan, P. 1997: Corruption and development: A review of the issues. Journal of Economic Literature 35 (3): 1320–1346.

Barry, F., Honohan, P. and McIndoe Calder, C. 2009: Postcolonial Ireland and Zimbabwe: Stagnation before convergence. Institute for International Integration Studies (IIIS) Discussion paper no. 291, 1 June. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1610301.

Bils, M. and Klenow, P. 2000: Does schooling cause growth or the other way around? American Economic Review 90 (5): 1160–1183.

Campos, N.F. and Coricelli, F. 2002: Growth in transition: What we know, what we don’t, and what we should. Journal of Economic Literature 40 (3): 793–836.

Dixit, A. 2004: Lawlessness and economics: Alternative institutions of governance, Chapter 1. Princeton University Press: Princeton, http://pup.princeton.edu/titles/7729.html.

Fischer, S. and Sahay, R. 2000: The transition economies after ten years. IMF Working paper WP/00/30, Washington DC.

Forteza, A. and Rama, M. 2006: Labor market ‘rigidity’ and the success of economic reforms across more than 100 countries. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 9 1: 75–105.

Gosh, A.R., Gulde, A. and Wolf, H.C. 2000: Currency boards: More than a quick fix? Economic Policy 15 (31): 269–335.

Gosh, A.R., Ostry, J.D and Tsangarides, C. 2010: Exchange rate regimes and the stability of the international monetary system. Occasional paper 270, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

Gylfason, T. 2006: How do India and China grow? Challenge 49 (1): 74–89.

Gylfason, T. and Hochreiter, E. 2009: Growing apart? A tale of two republics: Estonia and Georgia. European Journal of Political Economy 25 (3): 355–370.

Hall, R.E. and Jones, C.I. 1999: Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (1): 83–116.

Havrylyshyn, O. 2001: Recovery and growth in transition: A decade of evidence. IMF Staff Papers 48 (Special): 53–87.

Henry, P.B. and Miller, C. 2009: Institutions versus policies: A tale of two islands. American Economic Review 99 (2): 261–267.

Klomp, J. and de Haan, J. 2009: Political institutions and economic volatility. European Journal of Political Economy 25 (3): 311–326.

Levy-Yeyati, E. and Sturzenegger, F. 2003: To float or to fix: Evidence on the impact of exchange rate regimes. American Economic Review 93 (4): 1173–1193.

Mankiw, N., Romer, G.D. and Weil, D.N. 1992: A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (2): 407–437.

Marshall, M.G. and Jaggers, K. 2001: Polity IV Project: Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2000. Available at http://www.cidcm.umd.edu./inscr/polity/.

Marsiliani, L. and Renström, T.I. 2007: Political institutions and economic growth. Economics of Governance 8 (3): 233–261.

Mauro, P. 1995: Corruption and growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (3): 681–712.

Mincer, J. 1974: Schooling, experience and earnings. Columbia University Press: New York.

Paldam, M. and Svendsen, G.T. 2000: An essay on social capital: Looking at the fire behind the smoke. European Journal of Political Economy 16 (2): 339–366.

Purifield, C. and Rosenberg, C. 2010: Adjustment under a currency peg: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania during the global financial crisis 2008–09. IMF Working paper WP 10/213, Washington DC.

Reinhart, C.M. and Rogoff, K.S. 2004: The modern history of exchange rate arrangements: A reinterpretation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (1): 1–48.

Sachs, J.D. and Warner, A.M. [1995] revised 1997, 1999: Natural resource abundance and economic growth. NBER Working paper 5398, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Senhadji, A. 2000: Sources of economic growth: An extensive growth accounting exercise. IMF Staff Papers 47 (1): 129–157.

Williamson, O. 2005: The economics of governance. American Economic Review 95 (2): 1–18.

World Bank. 2009: World development indicators 2009. The World Bank: Washington DC.

World Bank. 2010: World development indicators 2010. The World Bank: Washington DC.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our discussant, Zuzana Murgasova, David Moore, Christoph Rosenberg, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments. Petra Vujakovic provided excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gylfason, T., Hochreiter, E. Growing Together: Croatia and Latvia. Comp Econ Stud 53, 165–197 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2011.4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2011.4