Abstract

This paper analyses the incidence of overeducation of university graduates. To this end, we estimate a random effects model for a panel of European countries. Our results do not confirm that the increase of the supply of qualified labour per se can be seen as a relevant factor fuelling overeducation. The relative wage of university graduates is inversely related to overeducation. This finding suggests a role for the demand for qualified labour. Cyclical conditions also matter, as overeducation operates as a short-term adjustment mechanism. This result sheds new light on the possible effects of the recession currently hitting the industrialized countries and on policy measures needed to foster economic recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the literature on overeducation based on individual-level data, a number of explanations of overeducation have been proposed. One of these maintains that it can derive from substitution between human capital acquired through formal learning at school and skills learnt through experience in the labour market (Sicherman, 1991) or from a poor quality of schooling (Ordine and Rose, 2009). In an analogous way, overeducation can be associated with lower individual ability (McGuinness, 2006). Otherwise, it can be caused by imperfect matching in the labour market due to a wrong distribution of educated workers by field of study, to spatial mismatch or to other imperfections. For a survey, see also Leuven and Oosterbeek (2011) and Quintini (2011b).

Correspondences between certificate of education and years of schooling are reported in Table 1.

Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Latvia, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia, the United Kingdom.

For thorough discussions of the different methods, see Borghans and de Grip, 2000; Hartog, 2000; McGuinness, 2006; Leuven and Oosterbeek, 2011.

In Quintini (2011a), the share of overeducated employees are derived from data collected by the European Survey of Working Condition (2005), by applying the statistical method based on the modal qualification in each occupation.

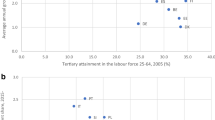

The Spearman test proves that the probability of independence between the ranks of the two distributions is equal to 0.6%.

We use the percentage of individuals aged between 25 and 64 with tertiary educational attainment in European countries provided by Eurostat.

In our definition, emphm corresponds to the ratio of the number of employees with tertiary degree to the number of employees with upper secondary degree (15–74 years).

Indeed, if the percentage of upper secondary graduates (in the population and in each occupation) is higher, also the percentage of overeducated tertiary graduates can be expected to be higher, just as a consequence of the spurious effect stemming from the definition of overeducation that we have adopted. We can exclude multicollinearity between poplau and popdip, as the correlation between them is only −0.2515 and not statistically significant.

ISCO 88 is coded on one digit as follows: (1) Legislators, Senior Officials and Managers; (2) Professionals; (3) Technicians and Associate Professionals.

The output gap is derived from the OECD Economic Outlook 2010 (issue 2) and is defined as the deviation of actual GDP from potential GDP as a percent of potential GDP.

More formal tests on the quality and validity of the instrument are reported in Appendix A.

Actually, firms would be prone to hire overeducated workers when returns to overeducation are low (Di Pietro and Urwin, 2006), besides the contractual arrangement. The possibility of hiring temporary workers could strengthen this behaviour.

Similarly, Dew-Becker and Gordon (2008) find that labour market reforms in Europe favoured a rise of employment of less experienced, less skilled components of the labour force and argue that this contributed to the productivity slowdown.

The unweighted average rate of long-term unemployment at the end of the period was equal to 3.24% compared with 4.13% in 1998.

References

Acemoglu, D . 2002: Technical change, inequality and the labor market. Journal of Economic Literature 40 (1): 7–72.

Agell, J and Lommerud, KE . 1992: Union egalitarianism as income insurance. Economica 59 (235): 295–310.

Barone, C and Ortiz, L . 2010: Overeducation among European university graduates: A comparative analysis of its incidence and the importance of higher education differentiation. Higher Education 61 (3): 325–337.

Borghans, L and de Grip, A . (eds). 2000: The debate in economics about skill utilization. In: The Overeducated Worker? The Economics of Skill Utilization. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham.

Bound, J, Jaeger, DA and Baker, RM . 1995: Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90 (430): 443–450.

Chun-Hung, AL and Chun-Hsuan, W . 2005: The incidence and wage effects of overeducation: The case of Taiwan. Journal of Economic Development 30 (1): 31–48.

Cutillo, A and Ceccarelli, C . 2010: The internal relocation premium: Are migrants positively or negatively selected? Evidence from Italy. Working Paper no. 137. Dipartimento di Economia e Diritto, Sapienza University of Rome, December.

Daly, MC, Büchel, F and Duncan, GJ . 2000: Premiums and penalties for surplus and deficits education. Evidence from the United States and Germany. Economics of Education Review 19 (2): 169–178.

Davia, MA, McGuinness, S and O’Connell, PJ . 2010: Explaining international differences in rate of overeducation in Europe. ESRI Working paper no. 365.

Dew-Becker, I and Gordon, RJ . 2008: The role of labour market changes in the slowdown of European productivity growth. CEPR Working paper no. 6722.

Di Pietro, G . 2002: Technological change, labor markets, and ‘low-skill, low-technology traps. Technological forecasting and social change 69 (9): 885–895.

Di Pietro, G and Cutillo, A . 2006: The effects of overeducation on wages in Italy: A bivariate selectivity approach. International Journal of Manpower 27 (2): 143–168.

Di Pietro, G and Urwin, P . 2006: Education and skills mismatch in the Italian graduate labour market. Applied Economics 38 (1): 79–93.

Dolton, P and Vignoles, A . 2000: The incidence and effects of overeducation in the U.K. graduate labour market. Economics of Education Review 19 (2): 179–198.

Dolton, P and Vignoles, A . 2002: Is a broader curriculum better? Economics of Education Review 21 (5): 415–429.

Duncan, GJ and Hoffman, SD . 1981: The incidence and wage effects of overeducation. Economics of Education Review 1 (1): 75–86.

Ghignoni, E . 2001: Frontiere di competenza, overeducation e rendimento economico dell’istruzione nel mercato del lavoro italiano degli anni ‘90. Rivista di Politica Economica 91 (6): 115–158.

Goldin, C and Katz, L . 2008: The race between education and technology. Harvard University Press: Harvard.

Goos, M, Manning, A and Solomons, A . 2010: Recent changes in the European employment structure: The roles of technology, globalization and institutions. CEP Discussion papers no. 1026.

Gottschalk, P and Hansen, M . 2003: Is the proportion of college workers in non-college jobs increasing? Journal of Labor Economics 21 (2): 449–471.

Groot, W and Maassen van den Brink, H . 2000: Overeducation in the labour market: A meta-analysis. Economics of Education Review 19 (2): 149–158.

Hartog, J . 2000: Over-education and earnings: Where are we, where should we go? Economics of Education Review 19 (2): 131–147.

Katz, LF and Autor, DH . 1999: Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality. In: Ashenfelter, O and Card, D (eds). Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol.3. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Katz, LF and Murphy, KM . 1992: Changes in relative wages, 1963–1987: Supply and demand factors. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (1): 35–78.

Leuven, E and Oosterbeek, H . 2011: Overeducation and mismatch in the labor market. IZA Discussion paper no. 5523.

McGuinness, S . 2006: Overeducation in the labour market. Journal of Economic Surveys 20 (3): 387–418.

McGuinness, S and Sloane, PJ . 2011: Labour market mismatch among UK graduates: An analysis using REFLEX data. Economics of Education Review 30 (1): 130–145.

Mendes de Oliveira, M, Santos, MC and Kiker, BF . 2000: The role of human capital and technological change in overeducation. Economics of Education Review 19 (2): 199–206.

Ordine, P and Rose, G . 2009: Overeducation and instructional quality: A theoretical model and some facts. Journal of Human Capital 3 (1): 73–105.

Ordine, P and Rose, G . 2011: Educational mismatch and wait unemployment. Almalaurea Working papers no. 19.

Ortiz, L and Kucel, A . 2008: Do fields of study matter for overeducation? The case of Spain and Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (4–5): 305–327.

Quintini, G . 2011a: Right for the job: Over-qualified or under-skilled? OECD social, employment and migration papers no. 120.

Quintini, G . 2011b: Over-qualified or under-skilled: A review of the existing literature. OECD social, employment and migration papers no. 121.

Sattinger, M . 1993: Assignment models of the distribution of earnings. Journal of Economic Literature 31 (2): 831–880.

Sicherman, N . 1991: Overeducation in the labour market. Journal of Labor Economics 9 (2): 101–122.

Sloane, PJ . 2003: Much ado about nothing? What does the overeducation literature really tell us? In: Buchel, F, de Grip, A and Mertens, A (eds). Overeducation in Europe. Current Issues in Theory and Policy. Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA.

Snower, D . 1996: The low-skill, bad-job trap. In: Snower, D and Booth, A (eds). Acquiring Skills. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Thurow, LC . 1975: Generating inequality. Basic Books: New York.

Tinbergen, J . 1975: Income distribution: Analysis and policies. North-Holland Publishing: Amsterdam.

Verdugo, R and Verdugo, N . 1988: The impact of surplus schooling on earnings. Journal of Human Resources 24 (4): 629–643.

Verhaest, D and van der Velden, R . 2010: Cross-country differences in graduate overeducation and its persistence. ROA Research Memorandum no. 7.

Walker, I and Zhu, Y . 2005: The college wage premium, overeducation, and the expansion of higher education in the UK. IZA Discussion paper no. 1627.

Wieling, M and Borghans, L . 2001: Discrepancies between supply and demand and adjustment processes in the labour market. Labour 15 (1): 33–56.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Tests on the quality and the validity of the instrument

As pointed out in preceding sections, the estimation of a model with instrumental variable needs at least one instrument that affects the wage ratio and not the incidence of overeducation. In this section, we test the quality and the validity of the instrumental variable we use in this paper (union coverage).

Instrumental quality is ensured if there is a strong correlation between the instrument and the wage ratio. A statistic commonly used in order to test this condition (Bound et al., 1995) is the R2 of the first stage regression with the included instrument ‘partialled-out’, or Shea partial R2 (for an application to the analysis of overeducation, see Di Pietro and Cutillo, 2006). In our first stage regressions, the partial R2 on the excluded instrument range from 0.47 to 0.63, suggesting that the instrument make a relevant contribution in explaining the wage ratio (see Table A1).

Instrumental validity is ensured if the instrument can be legitimately excluded from the overeducation equation. This assumption is often checked through the Sargan test. Nevertheless, this test is valid only in case of over-identification (ie, the number of valid instruments exceeds the number of endogenous variables), which is not our case. Following the suggestion of Cutillo and Ceccarelli (2010), we checked the validity of the instrument through the approach of Dolton and Vignoles (2002). According to these authors, a valid instrument must be uncorrelated with the error term of the outcome equation, and thus it should not affect the incidence of overeducation conditional on the included explanatory variables. When the residuals from the overeducation equations were regressed on the instrument, we obtained R2 ranging from 0.0002 to 0.0041 (see again Table A1). This indicates that the instrument does not explain any significant variation in the residual variability and hence is valid.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Croce, G., Ghignoni, E. Demand and Supply of Skilled Labour and Overeducation in Europe: A Country-level Analysis. Comp Econ Stud 54, 413–439 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2012.12

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2012.12