Abstract

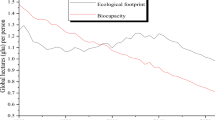

Using comparable 2002–2011 data, we examine the effect of oil on growth of Russia’s regions and American states. Although Russia’s oil regions are richer than other regions, they did not grow faster, while US oil producers grew faster than other states. We attribute these differences to different taxation systems in Russia and the United States, with the Russian central government taxing away a larger share of incremental oil rents in the 2000s than did its US counterpart. Moreover, although oil rents attracted labor to oil-producing regions both in Russia and the United States, only in the US oil rents led to higher investment growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The early examples of this mostly empirical literature include Auty (1993) and Sachs and Warner (1995). Recent surveys of this literature include Frankel (2010) and van der Ploeg (2011).

See Papyrakis and Raveh (2014) for Canadian provinces; Zhang et al. (2007), Fang et al. (2009), and Zuo and Schieffer (2014) for Chinese provinces; Papyrakis and Gerlagh (2007) for the US states and James and Aadland (2011) for US counties; and Desai et al. (2005), Lugovoy et al. (2007), Freinkman and Plekhanov (2009), Libman (2013), and Alexeev and Chernyavskiy (2014) for Russia.

See, for example, Kuboniwa (2012).

Russia’s tax system was radically changed with the introduction of the Tax Code in 2001, see Alexeev and Conrad (2013) and references therein.

In particular, both Papyrakis and Gerlagh (2007) and James and Aadland (2011) rely exclusively on cross-sectional regressions, which is particularly problematic in the former paper’s case because it severely limits the number of observations. Libman (2013) runs some panel regressions as a robustness check, but emphasizes on cross-sectional analysis, presumably because his focus is on the interaction between oil wealth and institutional quality, including the quality of the bureaucracy, and the data on the latter are available only for 1 year.

Interaction terms in this context were used, for example, by Mehlum et al. (2006). The ‘controls’ are put in quotes, because these are sometimes variables that are endogenous with GRP or its growth rate, for example, institutional quality or investments.

Brückner et al. (2012) use logarithm of GDP as the dependent variable. Strictly speaking, they regress the change in the logarithm of GDP on the change in the logarithm of the resource measure, which is in effect the first differenced regression of logarithm of GDP on logarithm of the resource measure. Brunnschweiler (2009) uses logarithm of growth rate as a dependent variable while her resource measure is not in growth terms.

For example, let region A produce 100 barrels of oil and region B produce 100 widgets. Year 1 price of a barrel of oil is 1 and the price of a widget is 1. In year 2, the price of oil rises to 3 and the price of a widget remains at 1, but ‘physical output’ stays constant implying that ‘physical volume’ index is 1. Then the deflator is (3 × 100+1 × 100)/(1 × 100+1 × 100)=2, and deflated output of region A is 3 × (100)/(2)=150 while the deflated output of region B is 1 × (100)/(2)=50.

No data on ‘physical volume’ GRP are available for the United States. Instead, we use GRP deflated by state-specific price indices.

Bruno (2005) proposed the bias-corrected Least Square Dummy Variable Estimator (LSDV) that appears to work better than system-GMM for relatively narrow samples as long as the right hand side variables are exogenous. This procedure yields positive point estimates of the concurrent oil abundance coefficients for the United States with per capita output significant at 1% level. Otherwise, the LSDV estimates are similar to the fixed effects and system-GMM estimates for both the United States and Russia using either 2001-based measures or concurrent measures of oil output. These results are available upon request.

It is possible that Russia’s oil companies do not increase investments in response to oil price increases because of their short-term orientation. This reasoning is not mutually exclusive with our main argument. Moreover, short-term thinking might be to a large extent caused by the predatory policies of the central government, including high rate appropriation of oil rents.

It is important to note that the Russian central government is probably aware of the negative effects of excessive extraction of regional rents and the particularly pernicious impact of the export fee. According to recently adopted legislation, the marginal rate of the export fee is supposed to decline from 0.6 in 2014 to 0.55 in 2016 while the base rate of the mineral tax on oil is scheduled to increase from 493 rules/ton in 2014 to 559 rubles/ton in 2016. Moreover, the central government is considering even faster reductions of the export fee and an increase in the mineral tax in the near future, motivated by the problems export fee causes in the presence of the customs union with Belarus and Kazakhstan (see http://www.minfin.ru/ru/press/speech/printable.php?id_4=21243).

References

Alexeev, M and Chernyavskiy, A . 2014: Natural Resources and Economic Growth in Russia’s Regions. NRU-HSE Working Papers, Series: Economics, WP BRP 55/EC/2014, Higher School of Economics: Moscow, Russia.

Alexeev, M and Conrad, R . 2009a: The elusive curse of oil. Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (3): 599–616.

Alexeev, M and Conrad, R . 2009b: The Russian oil tax regime: A comparative perspective. Eurasian Geography and Economics 50 (1): 93–114.

Alexeev, M and Conrad, R . 2011: The natural resource curse and economic transition. Economic Systems 35 (4): 445–461.

Alexeev, M and Conrad, R . 2013: Russian tax system. In: Alexeev, M and Weber, S (eds). The Oxford Handbook of the Russian Economy. Chapter 10. Oxford University Press: New York.

Auty, RM . 1993: Sustaining development in mineral economies: The resource curse thesis. Routledge: London.

Brückner, M, Ciccone, A and Tesei, A . 2012: Oil price shocks, income, and democracy. Review of Economics and Statistics 94 (2): 389–399.

Bruno, G . 2005: Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters 87 (3): 361–66.

Brunnschweiler, C . 2009: Oil and growth in transition countries. OxCarre Research Paper 29, Oxford Centre for the Analysis of Resource Rich Economies: Oxford, UK.

Desai, RM, Freinkman, L and Goldberg, I . 2005: Fiscal federalism in rentier regions: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Comparative Economics 33 (4): 814–834.

Fang, Y, Qi, L and Zhao, Y . 2009: The ‘curse of resources’ revisited: A different story from China. mimeo, available at http://ecademy.agnesscott.edu/~lqi/documents/reviewdocuments/2_The%20Curse%20of%20Resources%20Revisited%20A%20Different%20Story%20from%20China.pdf, accessed 7 May 2014.

Frankel, J . 2010: The natural resource curse: A survey. BNER Working Paper No. 15836, Harvard Kennedy School: Boston, MA.

Freinkman, L and Plekhanov, A . 2009: Fiscal decentralization in rentier regions: Evidence from Russia. World Development 37 (2): 503–512.

James, A and Aadland, D . 2011: The curse of natural resources: An empirical investigation of U.S. Counties. Resource and Energy Economics 33 (2): 440–453.

Kubiniwa, M . 2012: Diagnosing the ‘Russian disease’: Growth and structure of the Russian economy. Comparative Economic Studies 54 (1): 121–148.

Libman, A . 2013: Natural resources and sub-national economic performance: Does sub-national democracy matter? Energy Economics 37 (C): 82–99.

Lugovoy, O, Dashkeyev, V, Mazayev, I, Fomchenko, D and Polyakov, E . 2007: Analysis of economic growth in regions: Geographical and institutional aspect. Consortium for Economic Policy Research and Advice, IET: Moscow.

Mehlum, H, Moene, K and Torvik, R . 2006: Institutions and the resource curse. Economic Journal 116 (508): 1–20.

Papyrakis, E and Gerlagh, R . 2007: Resource abundance and economic growth in the United States. European Economic Review 51 (4): 1011–1039.

Papyrakis, E and Raveh, O . 2014: An empirical analysis of a regional Dutch disease: The case of Canada. Environmental and Resource Economics 58 (2): 179–198.

Regiony. various years: Regiony Rossii: sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie pokazateli, available at http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/publications/catalog/doc_1138625359016, accessed at various dates.

Sachs, JD and Warner, AW . 1995: Natural resource abundance and economic growth. Harvard Institute for International Development, Development discussion paper no. 517: Boston, MA.

Tokarev, AN . 2004: Izmeneniia v nalogooblozhenii neftegazovogo sektora: uchteny li interesy syr'evykh regionov. Nalogi. Investitsii. Kapital. Issue 2, http://nic.pirit.info/200404/056.htm, accessed 11 September 2014.

van der Ploeg, F . 2011: Natural resources: Curse or blessing? Journal of Economic Literature 49 (2): 366–420.

Yamarik, S . 2013: State-level capital and investment: Updates and implications. Contemporary Economic Policy 31 (1): 62–72.

Zhang, X, Xing, L, Fan, S and Luo, X . 2007: Resource abundance and regional development in China. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00713, International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington DC.

Zou, N and Schieffer, J . 2014: Are resources a curse? An investigations of Chinese Provinces. A paper prepared for presentation at the Southern Agricultural Economics Association (SAEA) Annual Meeting, 1–4 February, Dallas, Texas.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants of the Pacific Rim 2014 Conference for their valuable comments. Alexeev’s work on this topic was in part supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation, grant No. 14.U04.31.0002 administered through the NES CSDSI. Chernyavskiy’s research on this topic has received funding from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alexeev, M., Chernyavskiy, A. The Effect of Oil on Regional Growth in Russia and the United States: A Comparative Analysis. Comp Econ Stud 56, 517–535 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.28

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2014.28