Abstract

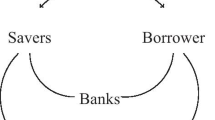

We model how an information asymmetry between the lending bank and the applying firm about the currency structure of firm revenues may affect loan currency choice. Our framework features a trade-off between the lower cost of foreign currency debt and the costs of currency induced loan default. We show that under imperfect information about firm revenues more local earners choose foreign currency loans, as they do not bear the full cost of the corresponding credit risk. This result is consistent with recent evidence showing that information asymmetries may increase foreign currency borrowing by retail clients in the transition economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In East Asia, corporate debt is split about equally between foreign and domestic currencies (Allayannis et al., 2003) while in several Latin American countries the share of foreign currency debt exceeds 20% (Galindo et al., 2003). Between 20% and 75% of all corporate loans in Eastern European countries are denominated in a foreign currency (European Central Bank, 2006, p. 39).

Foreign currency loans create serious challenges to policymakers. Countries with high volumes of foreign currency loans are more vulnerable to financial crises and more prone to spillover effects of country-specific shocks (see, eg, Cetorelli and Goldberg, 2011). Furthermore, foreign currency-denominated loans distort the transmission of monetary policy, influence the available credit in the economy, and therefore can impact the catching-up process of transition countries (see, eg, Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer, 2010).

In contrast to these two studies, others have examined foreign currency borrowing by analyzing aggregate cross-country data (eg, Luca and Petrova, 2008; Rosenberg and Tirpák, 2009; Basso et al., 2011) or the currency denomination of debt of large firms within a single country (Keloharju and Niskanen, 2001; Benavente et al., 2003; Gelos, 2003; Kedia and Mozumdar, 2003; Cowan et al., 2005) or across countries (Rajan and Zingales, 1995; Booth et al., 2001; Allayannis et al., 2003; Cowan, 2006; Esho et al., 2007; Kamil and Sutton, 2008; and Kamil, 2009). Clark and Judge (2008) provide a review of the relevant empirical literature.

We will not discuss: (1) International taxation issues such as tax loss carry forwards and limitations on foreign tax credits; (2) The possibilities for international income shifting; (3) The differential costs across countries of derivatives to create synthetic local debt; and (4) Clientele effects in issuing public bonds. These issues are clearly important when analyzing the debt structure of large corporations.

See, for example, Dollar and Hallward-Driemeier, (2000). In addition, banks often cannot verify firm sales information through advanced cash management services, which are yet to be introduced there, either because banks do not offer these services (eg, Tsamenyi and Skliarova, 2005) or firms do not demand them (eg, in the survey analyzed in Brown et al., 2011, one-third of the firms report receiving less than one third of their income through their banks). Banks may also lack information on firm quality, project choice, or managerial effort, eg, incurring monitoring costs (Diamond, 1984; Diamond, 1991) or forming relationships with the firms (Sharpe, 1990; Rajan, 1992; von Thadden, 2004; Hauswald and Marquez, 2006; or Egli et al., 2006, among others). Also other financiers may face more information asymmetries in transition and developing countries (eg, Claessens et al., 2000).

See Friberg and Wilander (2008). Firm risk aversion (Viaene and de Vries, 1992), currency variability (Engel, 2006), and medium of exchange considerations (Rey, 2001) may determine currency choice.

If the firms’ cash flows are in foreign currency, borrowing in the same foreign currency will provide a straightforward natural hedge (Goswami and Shrikhande, 2001). Mian (1996), Bodnar et al. (1998), Allayannis and Ofek (2001), and Brown (2001), among others, analyze the hedging of foreign currency exposure, using forward contracts and derivatives for example. But many developing country currencies have no forward markets; and even in those that do, there are substantial costs to hedging (Frankel, 2004). And even in developed countries, small firms rarely use derivatives to hedge their net currency exposure (Briggs, 2004; Børsum and Ødegaard, 2005; and O’Connell, 2005, among others). As expected, therefore, small firms in developing countries not uncommonly default on loans in foreign currency following a deep depreciation of the local currency (Ziaul Hoque, 2003). Static capital structure trade-off theory suggests firms opt for the lowest cost debt, making the interest rate differential, that is, the deviations from the UIP, the second main determinant of the firm's choice of loan currency denomination (Graham and Harvey, 2001).

As we later assume that the level of firm revenues does not change with the exchange rate, the changes in the exchange rate in our model are assumed to be real.

For a richer model in which firms also differ with respect to their debt-to-income levels, see the SNB Working Paper version of our paper (Brown et al., 2009b).

See Goldberg and Knetter (1997), for example, on exchange rate pass-through.

Firms in our model receive both their expected income and their loan in a single, though not necessarily the same, currency. Without qualitatively affecting the main hypotheses, our model is readily extendable to include firms that receive their expected income and loans in varying proportions in multiple currencies.

This is a crucial assumption in our model. If the UIP holds then the local currency earners will not have any incentive to borrow in foreign currency, as they will only bear higher costs either in terms of higher interest rate and/or in terms of prevailing distress costs.

General reviews by Hodrick (1987), Froot and Thaler (1990), Lewis (1995), Engel (1996), for example. For emerging markets, see Francis et al. (2002) and Alper et al. (2009).

Given our focus, we do not derive the optimality of this debt contract (see Townsend, 1979,eg).

For example, this corresponds to the risk aversion of managers, as in Stulz (1984), or of firms, as in Calvo (2001).

As financially distressed firm may lose customers, suppliers, and/or employees depending on the characteristics of their products and labor contracts for example, financial distress costs are also assumed to be heterogeneous across firms in Purnanandam (2008). Andrade and Kaplan (1998) estimate that financial distress costs vary between 10% and 20% of firm value (see also the review by Senbet and Seward, 1995). For small firms, both the level and dispersion of these costs are likely to be even higher (eg, Pindado et al., 2006).

See the SNB Working Paper version of our paper (Brown et al., 2009b) for a model with a continuous distribution of firms’ distress costs. A discrete distribution makes the analysis more elegant, yet does not alter the main intuition that imperfect information leads to more foreign currency borrowing.

In our model, all banks are equally affected by the information asymmetry regardless of the currency in which they lend. Most domestic and foreign banks in Eastern Europe, for example, offer loans in both local and foreign currency to local firms (see Brown et al., 2011 and Brown et al., 2012). If financiers lend only in their own currency, existing models predict that: (1) Firms may borrow first in the local and then in the foreign currency, after having exhausted internal funds, if local financiers have better information about the firm than foreign financiers (pecking order hypothesis); (2) Firms with high monitoring costs may borrow more locally in the local currency (Diamond, 1984); and (3) Better firms may borrow in the foreign currency to signal their quality, if foreign currency debt is more expensive (Jeanne, 1999) or entails more regulatory scrutiny hence higher distress costs (Ross, 1977).

References

Allayannis, G, Brown, GW and Klapper, LF . 2003: Capital structure and financial risk: Evidence from foreign debt use in East Asia. Journal of Finance 58 (6): 2667–2709.

Allayannis, G and Ofek, E . 2001: Exchange rate exposure, hedging, and the use of foreign currency derivatives. Journal of International Money and Finance 20 (2): 273–296.

Alper, E, Ardic, OP and Fendoglu, S . 2009: The economics of the uncovered interest parity condition for emerging markets. Journal of Economic Surveys 23 (1): 115–138.

Andrade, G and Kaplan, SN . 1998: How costly is financial (not economic) distress? Evidence from highly leveraged transactions that became distressed. Journal of Finance 53 (5): 1443–1493.

Basso, HS, Calvo-Gonzalez, O and Jurgilas, M . 2011: Financial dollarization: The role of foreign-owned banks and interest rates. Journal of Banking and Finance 35 (4): 794–806.

Beer, C, Ongena, S and Peter, M . 2010: Borrowing in foreign currency: Austrian households as carry traders. Journal of Banking and Finance 34 (9): 2198–2211.

Benavente, JM, Johnson, CA and Morande, FG . 2003: Debt composition and balance sheet effects of exchange rate depreciations: A firm-level analysis for Chile. Emerging Markets Review 4 (4): 397–416.

Berger, AN and Udell, GF . 1995: Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance. Journal of Business 68 (3): 351–381.

Berger, AN and Udell, GF . 2002: Small business credit availability and relationship lending: The importance of bank organisational structure. Economic Journal 112 (477): 32–53.

Berger, AN and Udell, GF . 2006: A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. Journal of Banking and Finance 30 (11): 2945–2966.

Bodnar, GM, Hayt, GS and Marston, RC . 1998: Wharton survey of financial risk management by us nonfinancial firms. Financial Management 27 (4): 70–91.

Booth, LV, Aivazian, A, Demirgüç-Kunt, A and Maksimovic, V . 2001: Capital structures in developing countries. Journal of Finance 56 (1): 87–130.

Børsum, ØG and Ødegaard, BA . 2005: Currency hedging in Norwegian non-financial firms. Norges Bank Economic Bulletin 9 (3): 133–144.

Briggs, P . 2004: Currency hedging by exporters and importers. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin 67 (4): 17–27.

Brown, GW . 2001: Managing foreign exchange risk with derivatives. Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2): 401–448.

Brown, M and De Haas, R . 2012: Foreign banks and foreign currency lending in emerging Europe. Economic Policy 27 (69): 57–98.

Brown, M, Jappelli, T and Pagano, M . 2009a: Information sharing and credit: Firm-level evidence from transition countries. Journal of Financial Intermediation 18 (2): 151–172.

Brown, M, Kirschenmann, K and Ongena, S . 2012: Bank funding, securitization and loan terms: Evidence from foreign currency lending. Center for Wealth & Risk Working Paper No. 170, University of St. Gallen: St. Gallen.

Brown, M, Ongena, S and Yeşin, P . 2009b: Foreign currency borrowing by small firms. Swiss National Bank Working Paper No. 2, Swiss National Bank: Zurich.

Brown, M, Ongena, S and Yeşin, P . 2011: Foreign currency borrowing by small firms in the transition economies. Journal of Financial Intermediation 20 (3): 285–302.

Calvo, GA . 2001: Capital markets and the exchange rate with special reference to the dollarization debate in Latin America. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 33 (2): 312–334.

Cetorelli, N and Goldberg, LS . 2011: Global banks and international shock transmission: Evidence from the crisis. International Monetary Fund Economic Review 59 (1): 41–76.

Claessens, S, Djankov, SD and Lang, LHP . 2000: The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics 58 (1): 81–112.

Clark, E and Judge, A . 2008: The determinants of foreign currency hedging: Does foreign currency debt induce a bias? European Financial Management 14 (3): 445–469.

Cowan, K . 2006: Firm level determinants of dollar debt? Mimeo, Central Bank of Chile: Santiago.

Cowan, K, Hansen, E and Herrera, LÓ . 2005: Currency mismatches in non-financial firms in Chile. Journal Economía Chilena – Chilean Economy 8 (2): 57–82.

Degryse, H, Havrylchyk, O, Jurzyk, E and Kozak, S . 2012: Foreign bank entry, credit allocation and lending rates in emerging markets: Empirical evidence from Poland. Journal of Banking and Finance 36 (11): 2949–2959.

Degryse, H, Masschelein, N and Mitchell, J . 2011: Staying, dropping, or switching: The impacts of bank mergers on small firms. Review of Financial Studies 24 (4): 1102–1140.

Detragiache, E, Tressel, T and Gupta, P . 2008: Foreign banks in poor countries: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance 63 (5): 2123–2160.

Diamond, DW . 1984: Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Review of Economic Studies 51 (3): 393–414.

Diamond, DW . 1991: Monitoring and reputation: The choice between bank loans and privately placed debt. Journal of Political Economy 99 (4): 689–721.

Dollar, D and Hallward-Driemeier, M . 2000: Crisis, adjustment, and reform in Thailand's industrial firms. World Bank Research Observer 15 (1): 1–22.

Egli, D, Ongena, S and Smith, DC . 2006: On the sequencing of projects, reputation building, and relationship finance. Finance Research Letters 3 (1): 23–39.

Engel, C . 1996: The forward discount anomaly and the risk premium: A survey of recent evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance 3 (2): 123–192.

Engel, C . 2006: Equivalence results for optimal pass-through, optimal indexing to exchange rates, and optimal choice of currency for export pricing. Journal of the European Economic Association 4 (6): 1249–1260.

Esho, N, Sharpe, IG and Webster, KH . 2007: Hedging and choice of currency denomination in international syndicated loan markets. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 15 (2): 195–212.

European Central Bank. 2006: EU banking sector stability. European Central Bank: Frankfurt.

European Central Bank. 2010: European stability review. European Central Bank: Frankfurt.

Francis, BB, Hasan, I and Hunter, DM . 2002: Emerging market liberalization and the impact on uncovered interest rate parity. Journal of International Money and Finance 21 (6): 931–956.

Frankel, JA . 2004: Experience of and lessons from exchange rate regimes in emerging economies. In: Asian development bank (ed). Monetary and Financial Integration in East Asia: The Way Ahead. Palgrave Macmillan Press: New York.

Freixas, X and Rochet, JC . 2008: Microeconomics of banking. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Friberg, R and Wilander, F . 2008: The currency denomination of exports – A questionnaire study. Journal of International Economics 75 (1): 54–69.

Froot, KA, Scharfstein, DS and Stein, JC . 1993: Risk management: Coordinating corporate investment and financing policies. Journal of Finance 48 (5): 1629–1658.

Froot, KA and Thaler, RH . 1990: Anomalies: Foreign exchange. Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (3): 179–192.

Galindo, A, Panizza, U and Schiantarelli, F . 2003: Debt composition and balance sheet effects of currency depreciation: A summary of the micro evidence. Emerging Markets Review 4 (4): 330–339.

Gelos, GR . 2003: Foreign currency debt in emerging markets: Firm-level evidence from Mexico. Economics Letters 78 (3): 323–327.

Goldberg, PK and Knetter, MM . 1997: Goods prices and exchange rates: What have we learned? Journal of Economic Literature 35 (3): 1243–1272.

Gorodnichenko, Y and Schnitzer, M . 2010: Financial constraints and innovation: Why poor countries don’t catch up? NBER Working Paper No. 15792, National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA.

Goswami, G and Shrikhande, MM . 2001: Economic exposure and debt financing choice. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 11 (1): 39–58.

Graham, JR and Harvey, CR . 2001: The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. Journal of Financial Economics 60 (2): 187–243.

Hauswald, R and Marquez, R . 2006: Competition and strategic information acquisition in credit markets. Review of Financial Studies 19 (3): 967–1000.

Hodrick, RJ . 1987: The empirical evidence on the efficiency of forward and futures foreign exchange markets. Harwood Academic Publishers: Chur.

Jeanne, O . 1999: Foreign currency debt and signaling. Mimeo, International Monetary Fund: Washington DC.

Jeanne, O . 2000: Foreign currency debt and the global financial architecture. European Economic Review 44 (4): 719–727.

Kamil, H . 2009: How do exchange rate regimes affect firms’ incentives to hedge currency risk in emerging markets? Mimeo, International Monetary Fund: Washington DC.

Kamil, H and Sutton, B . 2008: Corporate vulnerability: Have firms reduced their exposure to currency risk. In: International monetary fund (ed). Regional Economic Outlook: Western Hemisphere. International Monetary Fund: Washington DC.

Kedia, S and Mozumdar, A . 2003: Foreign currency-denominated debt: An empirical examination. Journal of Business 76 (4): 521–546.

Keloharju, M and Niskanen, M . 2001: Why do firms raise foreign currency denominated debt? European Financial Management 7 (4): 481–496.

Lewis, K . 1995: Chapter 37: Puzzles in international financial markets. In: Grossman, G and Rogoff K (eds). Handbook of International Economics, Vol. III. Elsevier: North-Holland.

Luca, A and Petrova, I . 2008: What drives credit dollarization in transition economies? Journal of Banking and Finance 32 (5): 858–869.

Mian, SL . 1996: Evidence on corporate hedging policy. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 31 (3): 419–439.

Nagy, PM, Jeffrey, S and Zettelmeyer, J . 2011: Addressing private sector currency mismatches in emerging Europe. In: Prasad, E and Kawai, M (eds). Financial Market Regulation and Reforms in Emerging Markets. Brookings Institution Press: Washington DC.

O’Connell, S . 2005: Currency game is risky for the smaller players. Sunday Times.

Pindado, J, Rodrigues, L and Torre, C . 2006: How does financial distress affect small firms’ financial structure? Small Business Economics 26 (4): 377–391.

Pistor, K, Raiser, M and Gelfer, S . 2000: Law and finance in transition economies. Economics of Transition 8 (1): 325–368.

Purnanandam, A . 2008: Financial distress and corporate risk management: Theory and evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 87 (3): 706–739.

Rajan, RG . 1992: Insiders and outsiders: The choice between informed and arm's-length debt. Journal of Finance 47 (4): 1367–1400.

Rajan, RG and Zingales, L . 1995: What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance 50 (5): 1421–1460.

Rey, H . 2001: International trade and currency exchange. Review of Economic Studies 68 (2): 443–464.

Rosenberg, CB and Tirpák, M . 2009: Determinants of foreign currency borrowing in the new member states of the EU. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance 59 (3): 216–228.

Ross, SA . 1977: The determination of financial structure: The incentive-signaling approach. Bell Journal of Economics 8 (1): 1–30.

Senbet, LW and Seward, JK . 1995: Financial distress, bankruptcy and reorganization. In: Robert AJ, Maksimović V and Ziemba WT (eds). Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science. Elsevier: Amsterdam.

Sharpe, SA . 1990: Asymmetric information, bank lending and implicit contracts: A stylized model of customer relationships. Journal of Finance 45 (4): 1069–1087.

Sorsa, P, Bakker, BB, Duenwald, C, Maechler, AM and Tiffin, A . 2007: Vulnerabilities in emerging southeastern Europe – How much cause for concern? IMF Working Paper No. 236, International Monetary Fund: Washington DC.

Stein, J . 2002: Information production and capital allocation: Decentralized versus hierarchical firms. Journal of Finance 57 (5): 1891–1922.

Stulz, RM . 1984: Optimal hedging policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 19: 127–140.

Townsend, RM . 1979: Optimal contracts and competitive markets with costly state verification. Journal of Economic Theory 21 (2): 265–293.

Tsamenyi, M and Skliarova, D . 2005: International cash management practices in a Russian multinational. Managerial Finance 31 (10): 48–64.

Viaene, J-M and de Vries, CG . 1992: On the design of invoicing practises in international trade. Open Economies Review 3 (2): 133–142.

von Thadden, E-L . 2004: Asymmetric information, bank lending, and implicit contracts: The winner's curse. Finance Research Letters 1 (1): 11–23.

Ziaul Hoque, M . 2003: Flawed public policies and industrial loan defaults: The case of Bangladesh. Managerial Finance 29 (2): 98–121.

Acknowledgements

We thank an anonymous referee for Comparative Economic Studies and an anonymous referee for the Swiss National Bank Working Paper Series, Raphael Auer, Söhnke Bartram, Henrique Basso, Katalin Bodnar, Josef Brada (the editor), Geraldo Cerqueiro, Andreas Fischer, Davide Furceri, Luigi Guiso, Werner Hermann, Herman Kamil, Anton Korinek, Marcel Peter, Alexander Popov, Maria Rueda Mauer, Philip Sauré, Linus Siming, Clas Wihlborg and seminar participants at the University of Amsterdam, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the University of Zurich, the Swiss National Bank, as well as participants at the European Finance Association Meeting (Bergen), the SNB-CEPR conference on ‘Foreign Currency Risk Taking by Financial Institutions, Firms and Households’ (Zürich), the Financial Intermediation Research Society Meeting (Prague), the CEPR/Studienzentrum Gerzensee European Summer Symposium in Financial Markets (Gerzensee), the European Economic Association Meetings (Milano), the CREDIT Conference (Venice), ESCE Meetings (Paris), the NBP-SNB Joint Seminar on ‘Challenges for Central Banks during the Current Global Crisis’ and the Tor Vergata Banking and Finance Conference (Rome) for useful comments and discussions. Ongena gratefully acknowledges the hospitality of the Swiss National Bank. Any views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Swiss National Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Proposition 1:

-

Under perfect information, all F firms take foreign currency loans. The equilibrium share of L firms that choose foreign currency loans is given as:

Proof.

-

Recall that the equilibrium interest rates on loans under perfect information can be written as:

Recall also that the expected payoff of firms can be written as:

and that the expected depreciation of the local currency is assumed to be 0:

Inserting the equilibrium interest rates from (A.2) into the expected payoff of firms (A.3), and using the equation (A.4), we obtain the following two results:

-

1

Foreign currency earners (F types) will always choose foreign currency loans, because their expected payoff will be higher when they take a foreign currency loan than when they take a local currency loan. Thus, all F firms will take foreign currency loans.

-

2

An L firm will choose a local currency loan when

The condition (A.5) tells us when it will be preferable for a local currency earner to borrow in foreign currency based on the values of the distress costs, the probability of depreciation, and the interest rate gap. In other words, a local currency earner will choose to take a local currency loan if its expected cost of default on a foreign currency loan is larger than the interest rate on local currency loans.Recall that we assumed only two values for

Thus if

Thus if  then all local currency earners will choose a foreign currency loan; and if

then all local currency earners will choose a foreign currency loan; and if  then no local currency earner will choose a foreign currency loan. For intermediate values of i

l

, only local currency earners with low distress costs,

then no local currency earner will choose a foreign currency loan. For intermediate values of i

l

, only local currency earners with low distress costs,  , will choose a local currency loan. Thus, the equilibrium share of L firms that choose foreign currency loans can be written as:

, will choose a local currency loan. Thus, the equilibrium share of L firms that choose foreign currency loans can be written as:

Note that (A.6) is equivalent to (A.1).

-

1

Proposition 2 (Separating Equilibrium):

-

If

then a separating equilibrium will emerge.

then a separating equilibrium will emerge.

Proof.

-

In a separating equilibrium, all local currency earners will choose a local currency loan by definition. Thus, we have the share of L firms taking a foreign currency loan equal to 0, that is, δ=0. Recall that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans can be written as:

Therefore, r f =0 when δ=0.Also recall that

From (A.8) it follows that a separating equilibrium exists, if

Proposition 3 (Partial Pooling Equilibrium):

-

If

and

and  a partial pooling equilibrium exists in which only L firms with low distress costs

a partial pooling equilibrium exists in which only L firms with low distress costs  take foreign currency loans while L firms with high distress costs

take foreign currency loans while L firms with high distress costs  take local currency loans.

take local currency loans.

Proof.

-

In a partial pooling equilibrium, some local currency earners will choose a local currency loan, whereas others will choose a foreign currency loan. Recall that distress costs can take only two values,

. Therefore, in a partial pooling equilibrium, the share of L firms that take a foreign currency loan should equal to the share of L firms that have low distress costs. Hence, δ=ϕ.Recall that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans can be written as in (A.7). Therefore,

. Therefore, in a partial pooling equilibrium, the share of L firms that take a foreign currency loan should equal to the share of L firms that have low distress costs. Hence, δ=ϕ.Recall that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans can be written as in (A.7). Therefore,

Substituting (A.9) into (A.8), it follows that only L firms with low distress costs will chose a foreign currency loan if:

and

Proposition 4 (Full Pooling Equilibrium):

-

If

a full pooling equilibrium exists in which all L firms take foreign currency loans.

a full pooling equilibrium exists in which all L firms take foreign currency loans.

Proof.

-

In a full-pooling equilibrium, all local currency earning firms take foreign currency loans, that is, δ=1. In this case, the expression (A.7) yields that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans is

Substituting (A.10) into (A.8), it follows that a full-pooling equilibrium exists if

Proposition 5 (Market Failure Imperfect Information):

-

Under imperfect information, there is no equilibrium in which foreign currency loans are extended if one of the following two conditions is met:

or

Proof.

-

Follows directly from propositions 2, 3, and 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, M., Ongena, S. & Yeşin, P. Information Asymmetry and Foreign Currency Borrowing by Small Firms. Comp Econ Stud 56, 110–131 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2013.9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ces.2013.9

Thus if

Thus if  then all local currency earners will choose a foreign currency loan; and if

then all local currency earners will choose a foreign currency loan; and if  then no local currency earner will choose a foreign currency loan. For intermediate values of i

l

, only local currency earners with low distress costs,

then no local currency earner will choose a foreign currency loan. For intermediate values of i

l

, only local currency earners with low distress costs,  , will choose a local currency loan. Thus, the equilibrium share of L firms that choose foreign currency loans can be written as:

, will choose a local currency loan. Thus, the equilibrium share of L firms that choose foreign currency loans can be written as:

then a separating equilibrium will emerge.

then a separating equilibrium will emerge.

and

and  a partial pooling equilibrium exists in which only L firms with low distress costs

a partial pooling equilibrium exists in which only L firms with low distress costs  take foreign currency loans while L firms with high distress costs

take foreign currency loans while L firms with high distress costs  take local currency loans.

take local currency loans. . Therefore, in a partial pooling equilibrium, the share of L firms that take a foreign currency loan should equal to the share of L firms that have low distress costs. Hence, δ=ϕ.Recall that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans can be written as in (A.7). Therefore,

. Therefore, in a partial pooling equilibrium, the share of L firms that take a foreign currency loan should equal to the share of L firms that have low distress costs. Hence, δ=ϕ.Recall that the equilibrium interest rate for foreign currency loans can be written as in (A.7). Therefore,

a full pooling equilibrium exists in which all L firms take foreign currency loans.

a full pooling equilibrium exists in which all L firms take foreign currency loans.