Abstract

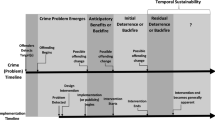

Planners of crime prevention evaluations often face a dilemma: how to actively manage numerous interacting variables needing prospective consideration as part of a research design. Failure to consider one design component at the expense of another, or lavishing disproportionate attention on some and not others can increase the likelihood of non-convincing and/or non-significant findings. To assist the decision-making processes needed at the initial stage of evaluation design to avoid such outcomes, we describe an evolving systematic prospective planning tool given the acronym CRITIC. CRITIC raises awareness, and discusses the effect, of Crime history (how crime-prone the action and control sites are), Reduction (in terms of proportional reduction in the crime problem anticipated in the action sites when compared to the control), Intensity (in terms of the number and/or strength of interventions necessary per target exposed to crime risk), Time period (that over which the action and control sites are tracked before and after implementation), Immensity (in terms of the number of units of analysis at risk of crime to be tracked) and Cost (in terms of the unit cost per intervention) on the likelihood of statistically significant outcome analyses and cost-effective results. The application of CRITIC is demonstrated on a bag-theft reduction study in a chain of bars in central London. Its wider utility to other crime prevention evaluation contexts is also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term troublesome tradeoffs was coined for highlighting the central task of design against crime in the real world, that of balancing design which is user-friendly whereas abuser-unfriendly. Its inclusion here is deliberate: creating evaluations that are fit for purpose is as much a matter of design, as creating the anti-theft clips that are the subject of this paper – evaluators having to envisage, and finesse, the optimum parameters for evaluation design.

‘herd immunity’ is a public health term referring to the situation when a critical proportion of animals (or humans) is immunised, at this point the rate of contagion becomes less than the ‘replacement level’ and the infection thus dies out. Ekblom and Sidebottom (2008) question if there similarly exists a critical proportion for crime prevention, in the present context, for example, where offenders judge bars as not worth entering to steal bags because of a perceived low likelihood of finding a bag which is not clipped and hence insecure.

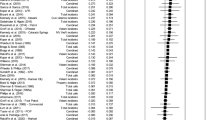

Problems have also been highlighted with the use of odds ratios in meta-analysis; in particular those associated with over-dispersion, which can be corrected for (see Farrington and Welsh, 2006).

Currently, the highest possible price is based solely on the mean reduction. It would also be possible to use the two confidence limit values to produce a 95% confidence interval range on the highest possible/break-even unit price.

References

Aos, S., Phillips, P., Barnoski, R. and Lieb, L. (2001) The Comparative Costs and Benefits of Programs to Reduce Crime. Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Washington: Olympia.

Baumer, E. and Wright, R. (1996) Crime seasonality and serious scholarship: A comment on Farrell and Pease. British Journal of Criminology 36: 579–581.

Bowers, K.J., Johnson, S.D. and Hirschfield, A. (2004) The measurement of crime prevention intensity and its impact on levels of crime. British Journal of Criminology 44 (3): 1–22.

Brantingham, P.J. and Brantingham, P.L. (2008) Crime Pattern Theory. In: R. Wortley and L. Mazerolle (eds.) Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis. Cullopmton: Willan, pp. 78–93.

Brown, S.E. (1989) Statistical power and criminal justice research. Journal of Criminal Justice 17: 115–122.

Burrell, A. and Erol, R. (2006) A Real Rise in Crime or Just a Passing Spate? The Example of Tyre Slashing in the West Midlands. Report Submitted to the Government Office for the West Midlands, April 2006. Retrieved 10 June 2007 from: http://www.jdi.ucl.ac.uk/downloads/briefings/tyre_slashing_briefing_note.pdf.

Bushway, S., Sweeten, G. and Wilson, D.B. (2006) Size matters: Standard errors in the application of null hypothesis significance testing in criminology and criminal justice. Journal of Experimental Criminology 2: 1–22.

Campbell, D.T. and Stanley, J.C. (1963) Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Cohen, J. (1977) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dubourg, R., Hamed, J. and Thorns, J. (2005) The Economic and Social Costs of Crime Against Individuals and Households 2003/04. London: Home Office. Home Office Online Report no. 30/05. Available from: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/rdsolr3005.pdf.

Eck, J.E., Clarke, R.V. and Guerette, R.T. (2007) Risky Facilities: Crime Concentration in Homogeneous Sets of Establishments and Facilities. In: G. Farrell, K. Bowers, S.D. Johnson and M. Townsley (eds.) Imagination for Crime Prevention: Essays in Honor of Ken Pease, Vol. 21. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press, pp. 255–264.

Ekblom, P. (1990) Evaluating Crime Prevention: The Management of Uncertainty. In: C. Kemp (ed.) Current Issues in Criminological Research, Vol. 2. Bristol: Bristol Centre for Criminological Research.

Ekblom, P. (1992) The safer cities programme impact evaluation: Problems and progress. Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 1: 35–51.

Ekblom, P. (2001) The conjunction of criminal opportunity: A framework for crime reduction toolkits. Available online at: http://www.crimereduction.homeoffice.gov.uk/learningzone/ccofull.doc.

Ekblom, P. (2005a) The 5Is Framework: Sharing Good Practice in Crime Prevention. In: E. Marks, A. Meyer and R. Linssen (eds.) Quality in Crime Prevention. Hannover: Landespräventionsrat Niedersachsen, pp. 55–84.

Ekblom, P. (2005b) Designing Products Against Crime. In: N. Tilley (ed.) Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety. Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing, pp. 203–244.

Ekblom, P., Law, H., Sutton, M. and Wiggins, R. (1996) Safer Cities and Domestic Burglary. London: Home Office. Home Office Research Study, 164.

Ekblom, P. and Pease, K. (1995) Evaluating Crime Prevention. In: M. Tonry and D.P. Farrington (eds.) Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention. Crime and Justice, Vol. 19. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 21–89.

Ekblom, P. and Sidebottom, A. (2008) What do you mean, ‘Is it secure?’ Redesigning language to be fit for the task of assessing the security of domestic and personal electronic goods. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 14: 61–87.

Farrell, G. and Pease, K. (1994) Crime seasonality: Domestic violence and domestic burglary in Merseyside. British Journal of Criminology 34 (4): 487–498.

Farrington, D.P. (2003) Methodological quality standards for evaluation research. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 587: 49–58.

Farrington, D.P. and Petrosino, A. (2001) The Campbell collaboration crime and justice group. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 578: 35–49.

Farrington, D.P. and Welsh, D.C. (2006) How important is ‘Regression to the mean’ in area-based crime prevention research. Crime Prevention and Community Safety 8: 50–60.

Gamman, L. and Pascoe, T. (2004) Design out crime? Using practice-based models of the design process. Crime Prevention and Community Safety Journal 6: 37–56.

Marchant, P. (2005) What works? A critical note on the evaluation of crime reduction initiatives. Crime Prevention and Community Safety: An International Journal 7 (2): 7–13.

Pawson, R. and Tilley, N. (1997) Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage.

Rosenbaum, D.P. (ed.) (1986) Community Crime Prevention: Does It Work? London: Sage.

Sherman, L.W. (2007) The power few: Experimental criminology and the reduction of harm. Journal of Experimental Criminology 3: 299–321.

Sherman, L.W., Gottfredson, D., MacKenzie, D., Eck, J., Reuter, P. and Bushway, S. (1997) Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What's Promising. Washington DC: National Institute of Justice.

Sidebottom, A. and Bowers, K.J. (forthcoming) Bag theft in bars: An analysis of relative risk, perceived risk and modus operandi. Security Journal, in press.

Smith, C., Bowers, K.J. and Johnson, S.D. (2006) Understanding theft within licensed premises: Identifying initial steps towards prevention. Security Journal 19 (1): 1–19.

Tilley, N. (2000) The Evaluation Jungle. In: S. Ballantyne, V. MacLaren and K. Pease (eds.) Secure Foundations: Key Issues in Crime Prevention, Crime Reduction and Community Safety. London, UK: Institute for Public Policy Research, pp. 115–130.

Weisburd, D. (2004) The Emergence of Crime Places in Crime Prevention. In: G.E.B. Bruinsma, H. Elffers and J. Keijser (eds.) Developments in Criminological and Criminal Justice Research. Cullompton: Willan Publishing, pp. 155–168.

Weisburd, D., Lum, C.M. and Yang, S. (2003) When can we conclude that treatments or programs ‘Don’t Work?’. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 587 (May): 31–48.

Weisburd, D., Petrosino, A. and Mason, G. (1993) Design Sensitivity in Criminal Justice Experiments. In: M. Tonry (ed.) Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, Vol. 17. Chicago: University of Chicago press, pp. 337–379.

Welsh, B. and Farrington, D. (2002) Crime prevention effects of closed circuit television: A systematic review. London: Home Office. Home Office Research Study no. 252.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper was funded by a research award from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (Award title: Turning the tables on crime: Boosting evidence of impact of Design Against Crime and the strategic capacity to deliver practical design solutions). The views expressed here are solely those of the authors. Thanks go to Professor Lorraine Gamman and colleagues at Central St Martins College of Art and Design.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bowers, K., Sidebottom, A. & Ekblom, P. CRITIC: A prospective planning tool for crime prevention evaluation designs. Crime Prev Community Saf 11, 48–70 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2008.20

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2008.20