Abstract

This article illustrates a Grounded Theory-based approach towards the discovery of the CRM Behaviour Theory. The CRM Behaviour Theory represents seven inter-related perspectives of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) relating to managing corporate customer relationships in service industries such as telecommunications. To gain a fresh perspective on CRM, an amended Glaserian Grounded Theory-based research methodology is proposed. This involved 52 personal interviews with service providers and their corporate clients. The results suggested taking a holistic view on CRM holons (a holon is defined as a system that is a whole system itself as well as being part of other systems) comprising seven interrelated pattern-like views. Leadership and an integrated approach are found to be critical, but not software. Software-centred approaches fail to deliver long-term results because of their exclusion of ‘soft’ issues, in particular organisational culture.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Much research has been conducted on Customer Relationship Management (CRM) since its academic emergence in 1997.1 After more than a decade, CRM for corporate clients in service industries such as telecommunications has been neglected in both academic and professional domains – often regarded as ‘quick fix’ technology projects.2 Many CRM approaches focus on mass markets and on related CRM initiatives such as retention and churn management.

CRM academics’ theoretical writings are often unrelated to business realities, consisting of overly abstract CRM models (Figure 3). CRM practitioners writing about the topic often address the success rate of technology-focused CRM software projects.3 However, CRM for corporate clients is very complex, in particular in service industries such as telecommunications. A tentative complexity analysis carried out during this research project uncovered more than 1400 CRM ‘hard’ activities for marketing, sales, customer service and billing. However, CRM for corporate clients is not just related to ‘hard’ factors. ‘Soft’ issues prevail in the business-to-business (B2B) world, where clients are known personally by supplier staff. CRM studies (Figure 3) and CRM market data4 propose a narrow view focusing just on CRM strategy, processes and systems. However, bearing in mind the actual complexity of CRM for corporate clients, perhaps Einstein5 described the best approach: ‘Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler’.

Notwithstanding the progress in CRM project success rates6 and wider academic propositions,7, 8, 9 CRM for corporate clients has never been fully explored,10 embracing both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ factors.11 This is the role of this article.

Evolution of research questions

Our research questions (RQs) evolved over time as an iterative, non-linear process (2002, 2004, 2007) in order to answer ‘what you specifically want to understand by doing your study’.12 In conclusion, we were trying to answer the major research question:

‘What are the evolved characteristics and behaviours of the holistic management of corporate customer relationships for telecoms carriers?’

This involved answering these further research questions:

-

RQ1: How are corporate customer relationships managed in the telecoms industry and what CRM models evolve?

-

RQ2: How do corporate clients behave and how are their requirements aligned with CRM models?

-

RQ3: What are the characteristics of performance management (PM) in business customers’ CRM?

-

RQ4: What are the inter-model, overall relationships of evolved holistic CRM model dimensions?

Interviewees’ understanding of CRM

As an introduction to the ‘real world’(pp. 116), Figure 1 presents an example of CRM for corporate clients in service industries, based on a 12-hour diary of a typical CRM ‘working day’ – extracted from the analysis of interview transcripts carried out by our research study. This diary reminds us of CRM complexity in theory and practice. Interviewees identify the gaps between claim and reality.

At the beginning of interviews, interview participants were asked to provide a short definition of their understanding about CRM. The objective was to ensure a mutual understanding of the terms used during the course of conduction of the interviews. Definitions varied between interviewees, depending on their expertise domain or personal background.

Here are some of the definitions of CRM reported by interview participants:

‘CRM is a philosophy and a strategy conception. And leaders shape the design of the relationship with our clients’. Director of quality assurance of a telecoms operator

‘For most sales people CRM is a piece of software deterring them from doing their job’. Key account manager for a fixed-network operator

‘CRM to me is: I am using CRM as a single system which provides you with a complete view of the customer’. Senior director for applications development of a metropolitan service provider

THE MISINTERPRETATION OF CRM IN THE LITERATURE

As indicated in the introduction section, significant research has been conducted on CRM since its academic emergence in 1997. However, the entirety of complex CRM has still not been properly explored. Instead, focused frameworks, for example, on CRM processes and technology, prevail,13, 14 categorising CRM as technology-centric. Even though scholars point out the neglect of causal interrelatedness between CRM model dimensions,15 they still ‘follow’ the same theoretical path as models criticised. The end result is explicit similarities of CRM frameworks propagating fundamental modelling errors (Figure 2). Shifting the perspectives towards academic analyses of professional CRM project failure, CRM scholars seem to reflect and learn very little from the identified causes of CRM failure – for example, the neglect of organisational change. On the other hand, many CRM managers ‘assume, that more CRM technology is better’.16 By contrast, some scholars17 describe CRM as a customer-centric business philosophy. What is more, Salomann et al18 point out that 48 per cent measure (hardly or not at all) CRM process performance and that corporate customers are neglected.

CRM in service industries

To better understand CRM for corporate clients, we need to identify the main differences between CRM for corporate clients and for consumers – the complexity of CRM for corporate clients. This is confirmed by Webster19 who argues that marketing for corporate clients, as one element of CRM, can be characterised by the complexity of products and purchase processes. Coviello and Brodie20 recognise that ‘marketing appears to be relational in B2B [business-to-business] firms and more transactional in consumer firms’ although there are key similarities, such as the approach to market planning. Gummesson21 adds that B2B CRM consists of ongoing business, whereas CRM for consumers focuses on everyday transactions. There is no active management of service-level agreements for consumers. Understanding corporate clients’ CRM demands an understanding of the organisational Theory of the Firm,22 as ‘an interplay of technology, social structure, culture, and physical structure’.23 A better elaboration of dynamic perspectives of CRM is needed to improve understanding of CRM causalities, that is, Systems Theory24 and Systems Thinking.25 CRM in service industries requires an understanding of principal service characteristics, which are virtually always neglected or ignored in the CRM literature. We also need to consider whether, from the point of view of CRM analysis, management of services differs from manufacturing management. A tentative answer is given by Normann26 who claims: ‘Yes and no’. Services can be evaluated and offered like nominal economic goods.27 Thus, both services and manufacturing goods can be classified as products.28 Second, Sasser et al29 recognise that services cannot be stocked, Levitt30 explores that service ‘production’ takes place in the field, whereas Normann emphasises that the customer is ‘a participant in the production of the service … [and ] … it is also necessary to ‘manage’ them as part of the production’.

CRM – Not just software

In the past, CRM was often seen as a ‘quick fix’ IT project proposal implemented by consultancies. According to Bergeron, CRM ‘was born around 1997’. Mack et al31 claim that CRM evolved from total quality management in the 1980s. Schmitt32 identifies the origin in the customer orientation movement in 1990s, whereas Newell33 recognises the strategic and technological focus of CRM. Auer34 states that US software vendors took up Relationship Marketing (RM) to market CRM systems. Bruhn refers to the continued usage of Relationship Marketing terminology, whereas Payne and Frow15 claim that CRM has ‘its roots in RM’ (p. 85). Later, Payne addresses the significance of change management in achieving positive CRM outcomes. Therefore, CRM thinking has evolved over the last decade, but there are differences of opinion as to how.

Our analysis of CRM literature revealed the emergence of three de-coupled ‘C-R-M Schools of Thought’ corresponding with the evolution of CRM. The separation of C-R-M is based on two analytical reflections: First, an ethnographic analysis35 of CRM: A ‘customer’ has a ‘relationship’ that is ‘managed’. Per se, this implies that clients – not ‘suppliants’, a terminology used by an interviewee of a corporate customer – are the starting point of CRM, rather than ‘R’ or the even prevailing end point ‘M’. Moreover, it implies that a customer has a relationship (‘R’) with personally known supplier staff – relationships with software would raise a rather different set of issues. Finally, it implies managers ‘M’ caring about the relationship (‘R’) with their customers (‘C’) rather than the opposite.

Second, the separation of C-R-M is additionally based on the allocation of scrutinised C-R-M models to global cultural traits36 clusters by applying the analysis principles of Grounded Theory (GT).

The iterative end result of this comprehensive analysis is: There is no unifying CRM modelling embracing the unifying CRM holism, but three distinct, geographically allocatable, partly overlapping, dis-unified CRM ideologies representing characteristic thinking about CRM as follows:

-

1

Managerial C-R-M School of Thought (relationships are monitored)

-

2

Process, IT and Implementation C-R-M School of Thought (relationships are technology-centred)

-

3

Markets and Stakeholder C-R-M School of Thought (relationships are stakeholder-centred)

A typical example of this absence of a unified CRM approach is the Strategic Framework for CRM and the CRM Value Chain,37 from the markets and stakeholder-centred C-R-M School of Thought: Both these models focus on markets and stakeholder, but propose different CRM viewpoints. There is some overlap with other ‘C-R-M Schools of Thought’, for example, Buttle's CRM Value Chain addresses implementation aspects as well. However, in our view a comprehensive description of CRM as a whole is not proposed by one particular School of Thought. In our view, contemporary C-R-M science is therefore weak, despite its volume. Ngai38 identified 105 CRM articles published in 2002. Parkinson's39 view that ‘the progress of science varies inversely with the number of journals published’ underlies Figure 3. By elaborating the nine C-R-M models, we can see that progress corresponds with dates of C-R-M publications. We believe that we need a fundamentally different research methodology, avoiding existing C-R-M propositions in order to avoid being ‘contaminated’.

GROUNDED RESEARCH METHODOLOGY – ENABLING A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON CRM

Research methodology

The requirements for a (CRM) publication are that the contribution to knowledge is original, relevant, communicable and trustworthy. Particular trustworthiness aspects include the credibility, controllability, validity and reliability of the contribution to knowledge.40 To address the unexplored holism of CRM, a qualitative research methodology41 emerged. A pre-condition for the understanding of this study is the tension from applying and advancing GT) principles for CRM in the telecoms industry – the fundamental paradigm controversy between GT founders Glaser and Strauss and Corbin.42 This resulted in the requirement for an amended GT research methodology that can be positioned43, 44 in the constructivism paradigm by drawing a line to postpositivism epistemology.45 The meaning to our CRM research is: Findings are expected to being objective, derived from actual, subjective CRM experience incorporating human values. On the basis of this, a GT methodology was designed incorporating two major principles:46, 47

-

1

Existing literature theories are not reviewed, but theories are discovered.

-

2

Theoretical elements are developed through coding procedures based on constant comparison of instances of data.

However, the paradigm controversy of Strauss and Corbin's evolved GT is positioned towards relativism (that is, multiple CRM realities exist) versus Glaser's ‘real’ realities, and virtually disregarded any discussion about vital GT modelling gaps and about a significant dilemma with regard to this study on CRM research. This is for two reasons:

-

1

The Glaserian position does not (intentionally) include a modelling ontology required for this research, but very useful coding families such as the ‘bread and butter’48 coding family ‘Six Cs’ (causes, context, contingencies, consequences, covariances conditions).

-

2

Strauss's position includes modelling propositions, but these are not useful for this CRM research confirming Urquhart's49 GT experience of having ‘broken apart (from) Strauss’ and Corbin's paradigm’.

These modelling gaps were addressed by iterative, normative GT research methodology amendments and included patterns,50 holons51 and abstract modelling.52 A pattern approach enabled the authors to identify CRM problems and solutions, that is, to answer the RQs (Introduction section). Constructing holons equipped us to explore dedicated CRM viewpoints and inter-linkages between them, that is, particularly to address RQ4 (What are the inter-model, overall relationships of evolved holistic CRM model dimensions?). Moreover, meta-modelling amendments provided an unambiguous classification of categories and properties representing abstract entities of CRM experiences, for example, ‘inconsistent design of CRM actions’ as stated by corporate client: ‘We were treated like residential customers … and billing as a complete horror’. The end result is the assembly of a grounded CRM behaviour theory as presented in Figure 4.

RESEARCH METHOD

Our grounded research method comprises three major components, adapted from Miles and Huberman41:

-

data collection including fieldwork preparation, that is, sampling method and broad fieldwork questions;

-

data reduction buttressed on amended GT principles; and

-

data display, that is, theory writing succeeded by the verification of findings.

Data collection

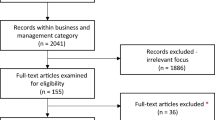

‘Lightly’ semi-structured interviews were the best way of discovering a CRM theory. These semi-structured interviews contained several broad, open fieldwork questions. Wengraf53 suggests that by applying this type of interview the (CRM) theory is likely to be discovered without reinventing the wheel or closing off the conceptual innovation. The unit of analysis was expected to be the marketing, sales, customer service and billing departments of service providers in mature telecoms markets in Europe, America and Asia/Pacific. In corporate clients, Information Technology (IT) departments of various industries, for example banking or publishing, typically purchasing Next Generation Services (NGS) such as broadband connections from telecoms best fitted the qualitative sampling. Fifty-two semi-structured depth interviews were conducted by a single interviewer from different organisational perspectives, of which 70 per cent were face-to-face interviews. The total elapsed time for data collection and analysis was 18 months, involving 46 600 miles (75 000 km) of global travel. The distribution is presented in Figure 5.

Data reduction

Collecting large amounts of interview data (a total of 596 pages of interview transcripts) requires much data management, recording and use of qualitative analysis software. This included preservation of raw data. NVivo and Decision Explorer software packages were used together with text processing for detailed code descriptions. Our grounded data analysis implied a set of coding procedures to analyse the meaning of interviewees’ experience, for example, memos, open and selective coding, as well as theoretical coding. Miles and Huberman define coding as the analysis of transcripts: not the words themselves but their meaning,41 that is, we derived meaning from interviewees’ statements rather than just rephrasing them.

We needed reliability and validity in data for the research to be valid.54 To address the question ‘Can one trust the results?’, we scrutinised and derived three meaningful criteria, as well as a consideration about the generalisability, as follows:

-

Internal postpositivism reliability (IPPR): 86 per cent intra-checker reliability. IPPR implied that interviewees were shown the results, and asked to what extent their CRM experience was reflected – rather than the widely used but entirely misjudging ‘do your peer student a favour’ feedback approach.

-

Constructionism (derive meaning from subjective interviews) transparency: A thorough documentation of executing GT coding procedures, including 596 pages of written interview transcripts.

-

Glaserian trust-building criteria: A rigorous layman's judgement of 4 months. This process involved four peer researchers and three CRM professional experts who judged the seeing and trusting the ‘big picture’ of the CRM findings.

-

Generalisability of results: Glaserian55 criterion of theory ‘modifiability over time’ by applying the findings in other and wider contextual environments.

As a reflective epilogue on ‘doing Grounded Theory’, we refer to Einstein56 who recognises: ‘There is no logical path to these laws. Only intuition, resting on sympathetic understanding of experience [which is helped by a feeling for the order lying behind the appearance], can reach them’.

FINDINGS – THE DISCOVERY OF THE CRM BEHAVIOUR THEORY

Structural approach to findings’ presentment

On the basis of the methodology approach, qualitative data were gathered from both telecoms operators and their corporate clients to answer the RQs. We were trying to answer the major RQ:

‘What are the evolved characteristics and behaviours of the holistic management of corporate customer relationships for telecoms carriers?’

This involved answering these further RQs:

-

RQ1: How are corporate customer relationships managed in the telecoms industry and what CRM models evolve?

-

RQ2: How do corporate clients behave and how are their requirements aligned with CRM models?

-

RQ3: What are the characteristics of PM in business customers’ CRM?

-

RQ4: What are the inter-model, overall relationships of evolved holistic CRM model dimensions?

Bearing in mind the requirement for a communicable and systematic findings’ structure, as well as non-hierarchical, multiple model perspectives, Figure 6 presents our approach and illustrates the sequence and linkages with the RQs:

Key findings overview

The purpose of this paragraph is to present key issues and propositions that emerged from the grounded data analysis, and to present a visual overview of fieldwork findings.

Interview participants stated that isolation in CRM, and particularly the complexity of CRM for corporate customers in the telecoms industry, requires a multi-perspective model. Five major CRM issues were revealed:

-

1

CRM managers have no common approach to CRM and lack a coherent and long-term direction in CRM.

-

2

CRM departments think and work in isolation and in parallel.

-

3

CRM processes and systems are designed in isolation and inconsistently managed.

-

4

Corporate customers are dissatisfied with inconsistent treatment and do not trust telecoms operators.

-

5

PM in CRM is network-centric focused and neglects corporate clients’ perceptions.

These central issues limit the ability of telecoms operators to manage corporate customer relationships. Five central propositions emerged to address the issues:

-

1

Leaders are willing to serve the CRM organisation and have genuine motives.

-

2

Create a motivating CRM culture with open communication and mutual trust.

-

3

Telecoms operators deliver a preferred customer experience to their corporate clients and sell services honestly and personally.

-

4

Corporate clients choose trusted, reliable and fast telecoms operators for their NGS solutions.

-

5

Outside-in PM addressed customer-centric ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ measures and inter-departmental key performance indicators (KPIs).

On the basis of the findings, detailed causal maps were designed that are presented throughout this part of the thesis. The conceptual CRM theory model overview is presented as follows:

Key findings statement

On the basis of the presentation of issues and propositions and the conceptual overview shown in Figure 7, the key finding of this research is:

‘A holistic CRM behaviour theory for telecoms operators and their relationships with corporate clients consisting of seven causally interrelated, problem-solution founded, non-hierarchical CRM perspectives based holons’.

SEVEN HOLISTIC CRM MODEL PERSPECTIVES

The seven models illustrate a systematically structured, non-hierarchical CRM approach for corporate clients in the telecoms industry and are as follows:

CRM Leadership model

This model deals with the behaviour of CRM managers in the telecoms industry. It is a central model consisting of 44 concepts (that is, properties and categories). The CRM leadership view addresses the interplay of self-centric progress (that is, personal objectives diametrical to CRM objectives), diversified CRM approaches and operational CRM problem solving with genuine, customer-centric motives and relevant leadership tasks and roles in CRM. CRM managers are at the centre of change activities and their different behaviours are analysed. Figure 7 briefly shows that mutual linkages with the organisation and strategy models were revealed at various management levels.

CRM Strategy model

This model addresses the long-term planning of CRM actions and different types of strategy behaviour. The strategy perspective plays a vital role in the overall CRM model, although it consists of 21 categories and properties, only. This viewpoint discusses the causal behaviour of non-aligned CRM programmes, CRM project failure, as well as understanding corporate clients’ requirements and personal sales of NGS. The improvement of CRM initiatives forms the analytical centre of the model. The model is mutually related to the customer and measurement views in particular.

CRM Organisation model

The organisation model discusses people-related behaviour in sales, marketing customer services and billing departments of telecoms operators. It is a central model, and consists of 44 concepts. The model deals with isolated thinking and working in CRM and the concepts required to address such issues. The conceptual focus is on structural changes towards interwoven customer-centric teams operating in trusted atmospheres. As can be seen in Figure 7, the model is closely linked with CRM processes, the customer perspective and the leadership model in various organisational CRM units.

CRM Process model

The process model deals with the execution of CRM programmes via operational activities in sales, marketing, customer service and billing. It is a central model consisting of 26 concepts, and reflects issues of unsatisfactory corporate customer experience and missing customer information handshakes. The design of an outside-in CRM process approach is at the model centre. The process model view is closely linked with organisation, systems, measurement and customer models.

CRM Systems model

The systems model addresses CRM software application-related behaviour in the telecoms industry. The model consists of 34 categories and properties and plays a vital role in automating CRM processes. It deals with monolithic and isolated CRM installations and their causal relationships with CRM systems architecture, dynamic CRM applications and embedded PM capabilities. The systems model is closely linked with the process model, in particular.

CRM Customer model

The customer model addresses the outside-in perspective of corporate customers about CRM. It is a central model linking external with internal CRM perspectives, and it consists of 34 categories and properties. It deals with inconsistent, standardised treatment of clients and missing long-term CRM commitment. The conceptual centre is formed by designing preferred methods of CRM interaction and NGS provider independence. There is a very close linkage with the strategy model as illustrated in Figure 7.

CRM Measurement model

This model deals with CRM performance management in the telecoms industry. Comprising 38 concepts, it is a central model and defines a bracket of internal and external model perspectives. It deals with the causal behaviour of isolated CRM measurement of both telecoms operators and their corporate clients and the lack of customer-relevant indicators in relation to conceptual elements. These concepts include a holistically connected framework from the outside-in. As presented in Figure 7, the model is closely linked with strategy and processes.

On the basis of the presentation of key findings, the next methodological step is the grounded allocation of actually relevant literature.

Locating the CRM Behaviour Theory to Relevant C-R-M Literature

This paragraph addresses the discussion of findings in the context of relevant literature. A set of five key differences with our findings was revealed:

-

Isolation, the key problem of all seven CRM perspectives is often neglected in CRM literature,57 although there was evidence in the fieldwork that separate execution of CRM activities has inter-model affects.

-

CRM culture and related ‘people business’ aspects of CRM for corporate clients emerged as the central CRM discussion perspective related to addressing isolation issues. However, the fieldwork findings demonstrated little similarities with the CRM literature, where a customer-centric motivating CRM culture was concerned.

-

PM requirements for CRM revealed by this fieldwork such as ‘measuring the right things’ and PM as a measurement theme in itself are disregarded in the CRM literature.58 A focus on ‘hard’ or financial measures for processes and internally directed benchmarks prevails.

-

The dynamic behavioural aspects discovered in our fieldwork are almost excluded in the literature focusing on conceptual59 or static views, neglecting causal relationships.

-

An integrative perspective on PM in CRM (CRMQUAL) incorporating the measurement of CRM culture, the conceptual separation of processes and systems measures, as well as non-hierarchical (that is, non-successive, unranked) feedback loops is not covered by the literature – in particular Kaplan and Norton's strategy maps.

Some parts of the CRM literature showed four key similarities, but relevant literature actually varies and does not show a single key criterion of similarity:

-

The literature partly recognises the ‘cross-functional nature’ of relationships. This has been confirmed by our fieldwork, which shows that a functional perspective (that is, Marketing, Sales, Customer Service, as well as Billing) would destroy behavioural understanding rather than support it. In fact, a functional perspective (that is, Marketing, Sales, Customer Service and Billing) was dissolved and concepts transformed into seven dedicated CRM views.

-

Payne and Frow15 indicate that isolation is a CRM issue, although no systematic approach is proposed as we suggest. Lovelock60 proposes a service quality gap model. The approach offers a partly similar problem awareness related to CRM, but falls short concerning some ‘soft’ issues such as motivation, and particularly managerial willingness to support CRM.

-

CRM culture is often addressed in the managerial School of Thought. This means that there is a contradiction in the CRM literature. However, Homburg and Sieben61 propose a customer-centric culture model that confirms the relevance of CRM culture and its impact on processes as well as the interaction with corporate clients.

-

PM in CRM revealed novel similarities. IMP Group suggests measures related to corporate clients’ requirements such as trust, reliability and flexibility, while Woodcock's proposition for a collective PM approach in CRM indicated that a lack of customer behaviour measures means valuable PM insights are disregarded.

The seven CRM perspectives were mapped against the literature, revealing fresh perspectives on CRM, as illustrated in Figure 8.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL CRM EXPERTS

Analytical reflective conclusions from interviewees’ perspectives

There is significant support for modelling actual CRM experience and episodes (fourth interviewee, 2007). The relevance of an outside-in perspective of corporate customers is confirmed: ‘I discussed your model with my colleagues. Our [corporate customer] experience is entirely reflected … the results are clearly understandable and logically structured’ (thirty-fifth Interviewee, 2007). This confirms Rigby et al, who suggest incorporating customer requirements in order to learn from previous CRM experiences. The seven dedicated CRM perspectives and their inter-linkages are confirmed. The fifteenth interviewee (2007) investigated the CRM strategy model and suggested that ‘Marketing is not needed in B2B, but a “fine” NGS solution image’. This indicates the balanced functional viewpoint of the CRM Behaviour Theory rather than focus just on marketing. The comprehensiveness of the theory was understood by CRM professionals (for example, fourteenth interviewee, 2006, 2007). This argument is supported by the result of an intra-checker reliability analysis of 86 per cent.

However, the CRM Behaviour Theory is criticised by interviewees and peer scholars who provided their rigorous feedback. Criticism concerns:

-

‘Heavyweight’ reading requires comprehensive attention.

-

Complexity is criticised by less experienced academic researchers.

It is said to be hard to understand quickly Grounded Influence Diagrams, owing to the large number of figures and proxies provided (thirty-fifth interviewee, 2007), although the thirty-fifth interviewee (ibid.) adds: ‘Once you are really acquainted with the subject, everything is understandable’. Moreover, the fourteenth interviewee (2007) adds that ‘it required 20 hours to read and to feedback on the organisation and measurement models’. Perhaps this means that both vast CRM experience and comprehensive academic analytic capabilities may be needed to understand the CRM Behaviour Theory. However, a limiting software issue in Decision Explorer is closely related: The numbering of visual models, in particular proxies that cannot be modelled as one but consecutively numbered representations, only. This limits the efficiency of reading Grounded Influence Diagrams, which was confirmed by interviewees reflecting on the findings.

With regard to the second major issue, findings are criticised by academic scholars who are inexperienced in modelling. In our view, this reflects the comprehensiveness of long-term CRM transformation projects. Conclusions revolve around the confirmation of results, as well as the cognition that a differentiated research methodology surfaces actual CRM issues and solutions. As a logical next step, conclusions on ‘doing’ GT are explored.

Conclusive suitability of the amended GT research methodology

The purpose of this paragraph is to evaluate the suitability of the amended GT research methodology approach to addressing the RQs. GT certainly facilitated a ‘fresh’ perspective on CRM (Figure 8) and the exploration of characteristics and behaviour of CRM from multiple viewpoints. However, the author was still contaminated, that is, influenced, by misleading, irrelevant C-R-M literature at the beginning (14 February 2005) of the evolution of tentative broad fieldwork questions. As discussed in the methodology section, a set of three normative amendments was developed to address existing GT modelling gaps. GT coding principles enabled the discovery of 242 CRM concepts grounded in 52 semi-structured interviews. Nevertheless, the author recognises that constructionism research, which is based on subjective experience, is not free of bias,42 and interpreting beliefs had to be suspended in order to bring to the surface theoretical CRM concepts. The evaluation confirms the suitability of GT to explore CRM for corporate clients in the telecoms industry and to enable a paradigm shift in CRM.

We experienced significant resistance while uncovering the CRM Behaviour Theory. GT research seems to uncover basic methodological issues, for example, in cognitive mapping. We learnt one important lesson: Perhaps Einstein56 best describes the methodological meaning of this GT methodology: ‘We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them’.

Conclusions on explicit and implicit contribution to knowledge: An instance of a general relationship behaviour theory?

The purpose of this paragraph is to draw conclusions on the contribution to knowledge from explicit and implicit viewpoints. Explicit perspectives are characterised by four evaluation criteria: originality, credibility, communicability and relevance.62 This is constituted in the fundamental questions of ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’.63 By contrast, implicit viewpoints emerged from cognitive holistic reflection and peer discourses. To fulfil these criteria, we conducted an almost ‘endoscopic’ analysis of 6-month end-to-end results’ testing and reflection. One particular criterion, originality, stands out: we are very much aware that the theory discovered is not based on entirely new concepts, but an analytic result of grounded data collection and data analysis based on an amended GT methodology. Hence, as for the generalisability of results, the fieldwork was only in the telecoms industry and the model as a whole was developed in this context and not evaluated or used in other industries. Any indications about the generalisability of the outcomes are not grounded in an empirical process. However, CRM is not a specific discipline developed for the telecoms industry, but marketing, sales, customer service and billing exist in almost every industrial context.

IMPLICATIONS

Implications for professional and academic CRM stakeholders

On the basis of the above conclusions, the next logical step is to explore applicable implications for a set of five relevant stakeholders of our research: CRM researchers, CRM lecturers and corporate customers, CRM employees as well as CRM leaders so as to ground our research in the professional domain. However, considering the research problem that uncovered implicit, hidden attitudes in CRM, a holistic understanding of attitude-behaviour implications is needed. Referring to Kleinke,64 an approach relevant to our research appears to be the application of ‘traditional attitude’ theories65, 66 enhanced by results changes67 as follows:

Implications for CRM researchers: Internalise critical, independent grounded thinking beyond CRM

The purpose of this paragraph is to explore implications of this thesis for CRM researchers. The literature section unveiled academic CRM issues related to over-simplification and error propagation of theoretical CRM propositions. Perhaps, Einstein's68 résumé best reflects upon this contemporary problem: ‘It is also vital to a valuable education that independent critical thinking be developed … a development that is greatly jeopardised’. The author witnessed eccentric hegemony and jealousy among scholars in the literature. Indeed, a good comparison of such behavioural issues to CRM leaders is stated by an interviewee as follows: ‘I am lucrative and you are empty-headed’. As a result, an attitude shift is needed as follows: ‘Be willing to develop critical, independent academic thinking in CRM’. This is based on the awareness of one's research paradigm and the refusal to uncritically accept CRM literature. The behavioural change implies the conduct of research independent from prominent academic institutions to address error propagation. The result of behavioural change is ‘rewarded’ with the discovery of innovative, integral CRM models and an in-depth understanding of the multidimensionality of CRM. One important side aspect is the philosophic cognition of research methodologies and understanding of grand scholars such as Einstein.

Implications for CRM lecturers: Integrate CRM issues for prospective professionals and stimulate intellectual activities

The purpose of this paragraph is to explore implications of this thesis for CRM lecturers. CRM lecturers often do not teach the ‘right things’ to prospective CRM professionals but refer to technology, abstract and misleading CRM case studies or ‘proven models’. This is further confirmed by discourses with three peers and 24 semesters of own experience as a research student. However, this seems to be a rather specific issue related to CRM as a discipline of applied sciences. Perhaps Einstein best describes the situation: ‘Numerous are the academic chairs, but rare are wise and noble teachers’. Hence, an attitude change is needed as follows: ‘Think beyond academic CRM disciplines and stimulate intellectual activities of students’. This is based on the awareness of the principal CRM modelling gaps such as sequential or hierarchical thinking. The implied change of behaviour focalises on teaching inter-disciplinary, grounded thinking and acting in CRM rather than another process automation lecture. Such lecturing is supported by the development of CRM examples from own experience rather than reprocessing abstract CRM case studies. The result is a stimulus of holistic intellectual activities of CRM students and the preparation of prospective CRM professionals for complex realities CRM ‘out there’. Perhaps the realistic outcome is recognised by Einstein: ‘Small is the number of people who see with their eyes and think with their minds’.

Implications for corporate customers: Improve purchasing conditions and become provider-independent

The purpose of this paragraph is to explore implications of the thesis for corporate clients and their relationships with telecoms operators. CRM issues identified, such as inconsistent treatment, are the ‘rule’ rather than exception in the telecoms industry. Corporate clients should not mistakenly assume that CRM issues are just related to their individual experiences with telecommunications operators. Therefore, as an implication, a change in attitude appears to be a logical, sound measure towards independence from suppliers, that is, engaging more than one telecoms operator and increasing competition among them. The implied change of attitude is: ‘Corporate clients are independent from telecoms operators’, that is, they can select NGS from a small pool of operators. However, attitude changes take effort and time, typically become very personal and require the willingness to feedback and learn. On the basis of such an attitude change, in particular CRM problem awareness, the behavioural change of negotiation conditions for the purchase of NGS solutions appear as follows: ‘You [operator] have one bid, only’. This is supported by systematically measuring ‘soft’ CRM aspects such as trust replacing ‘gut feeling’. The result is independence from suppliers, although a caring dialogue supports the long-term perspective of the relationship with telecoms operators.

Implications for CRM employees: Think honestly from outside-in corporate customer viewpoints and across CRM boundaries

The purpose of this paragraph is to explore implications of this thesis on CRM employees in the telecoms industry. Employee issues in CRM are related to thinking and working in isolated, artificial boundaries. Perhaps a good example is NGS sales behaviour, which has been described by a service delivery engineer of a mobile operator as ‘sell and forget’ accompanied by a ‘treat marketing as your enemy’ attitude. Therefore, a change in CRM employee attitude is the logical implication of the thesis that appears as follows: ‘Think honestly from outside-in, about corporate customers’ viewpoints and across CRM boundaries’. This is based on the trusting of other CRM employees in an open atmosphere. The behavioural change involves the adaptation and execution of CRM processes from an outside-in corporate customer experience to address, for example, the problem that the ‘left hand does not know what the right hand is doing’ conduct as expressed by the thirty-eighth interviewee in the fifth quotation [38–05]. Such a conduct is supported by designing measuring inter-departmental KPIs and the listening to and interacting with corporate clients. However, CRM employees should not imitate behavioural issues related to CRM leaders, but become ‘men of value’.68 The result is the ability to operate in motivated, customer-centric teams and interwoven CRM processes and the linking of disconnected CRM and PM. One important side effect is the understanding of corporate clients.

Implications for CRM leaders: Be willing to serve the CRM organisation, understand corporate customers and manage complexity

The purpose of this final paragraph is to explore implications of this thesis for CRM leaders in the telecoms industry. A figurative sense of Einstein's cognition is required: the issue in CRM leadership is not intellect but ‘character’. Of 17 interviewees asked about CRM leadership 12 reported that a focus on self-centred personal progress of CRM managers was closely related to the lack of a common CRM approach among leaders. Such behaviour affects the entirety of CRM; to put it mildly, CRM problems start at the top and return to the top. Therefore, a change in CRM leadership attitude is the logical implication of the thesis. The implied change of attitude is: ‘Be willing to serve the CRM organisation and corporate clients’. This is based on a genuine desire to lead CRM, a thoughtful CRM leadership style and the trusting of CRM employees. Our findings support both bringing to the surface CRM leadership problems and solutions, as well as the awareness of the consequences. The behavioural change implies performing CRM leadership tasks such as understanding corporate customers and employee requirements rather than just solving operations issues. Talking to corporate clients and employees personally and openly reinforces the change, accompanied by measuring the ‘right things’ in CRM and a step-by-step change. The result is the ability to manage CRM complexity in the long run rather than just understanding CRM technology. Moreover, the behavioural change enables CRM leaders to understand ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ corporate customer CRM requirements.

Epilogue: A redefinition of CRM

The purpose of this paragraph is to critically rethink the actual meaning of CRM to the authors as it emerged after the fieldwork. A rigorous, retrospective comparison with the stereotypical software-centred working definition of CRM defined before the grounded fieldwork reveals that the understanding of CRM was nothing more than a contaminated, derivative re-processing of prevailing CRM definitions. Indeed, we were just rephrasing other scholar's thinking without understanding the meaning of CRM in the complex real world of business. The end result was a redefinition of CRM.

‘Customer Relationship Management (CRM) for corporate customers in the telecoms industry is a long-term customer- and total quality management-centred business philosophy to address the two core CRM issues of, firstly, self-centric leadership behaviour in CRM and, secondly, working and thinking in isolation in Marketing, Sales, Customer Service and Billing “silos”. CRM is based on seven causally interrelated, non-hierarchical perspectives that emerged from, and are grounded in, actual CRM experience rather than abstract metaphors of information technology-centricity. At the centre is the outside-in understanding and integration of “hard” and “soft” corporate customer CRM requirements. The transformational CRM nucleus is a personal attitude change of CRM leaders, to become willing to serve the CRM organisation and corporate customers, enabling a motivating CRM culture to “glue” prevailing isolation. CRM change is supported by a seven-dimensional, problem-solution-founded CRM dashboard to address existing fragmented and misleading measurement in CRM. The emerging CRM holism enables the understanding of the actual complexity of CRM for business customers and the effective management of CRM, as well as the recognition of behavioural CRM patterns in a “people business” environment’.

Further research – Significant research-related work to be addressed

The purpose of this paragraph is to explore other research subjects that emerged from data analysis and collective reflection. The most obvious research subjects are explored exemplarily, now.

First, applying and testing the CRM Behaviour Theory in other (service) industries appears the most obvious step. Perhaps the trust-centred financial service industry is a good candidate, particularly given the current issues with financial services. What is clear from our research is that researchers should directly interview corporate clients to grasp a multi-perspective understanding of CRM behaviour. Front and back-office employees should also be interviewed, in particular contact centre customer service representatives (CSRs). Scholars should approach CSRs independently from their managers in order to ensure an open interview atmosphere. Of course, CRM managers should also be interviewed. Perhaps the most relevant advice is: first, let interviewees ‘tell their stories’, and second let concepts emerge while coding interview transcripts.

Second, based on research topic number one, we intend to address the research topic ‘Discovery of the General Relationship Behaviour Theory (GRBT)’ by tentatively adapting our research into a general context, that is, other service industries, non-service industries and particularly society as an ‘ultimate general’ context.

Third, we propose to revisit this research in 2014. This particular date is based on the idea of the diminishing progress of science, according to which concepts change ‘in time and space’ after 7 years.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

Bergeron, B. (2002) Essentials of CRM: A Guide to Customer Service Relationship Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 2.

Bruhn, M. (2001) Relationship Marketing: Das Management von Kundenbeziehungen [Relationship Marketing: Management of Customer Relationships]. Munich, Germany: Verlag Franz Vahlen, p. VI.

Gartner Group. (2003) Building Business Benefits from CRM. Stamford, CT: Gartner Group.

Mertz, S. (2008) CRM Software Market to Grow 14 Percent in 2008. Stamford, CT: Gartner Group.

Einstein, A. (1934) On the method of theoretical physics. Philosophy of Science 1: 32.

Band, W. (2007) The Forrester Wave: Enterprise CRM Suites. Cambridge, MA: Forrester.

Buttle, F. (2000) The CRM Value Chain. Sydney: Macquarie University, also published in Marketing Business, 2001, February, pp. 52–55.

Payne, A. (2006) Handbook of CRM: Achieving Excellence through Customer Management. Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

EFQM. (1991) European Quality Management Forum. European Quality Management Forum. Paris: European Foundation for Quality Management.

IMP Group. (2002) An interaction approach. In: H. Hakansson (ed.) International Marketing and Purchasing of Industrial Goods. Chichester, UK: Wiley & Sons.

Glaser, B.G. (1998) Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press, p. 31.

Maxwell, J.A. (2005) Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, p. 65.

Österle, H., Schmid, R.E. and Bach, V. (2000) Mit customer relationship management zum Prozessportal [CRM and process portals]. In: H. Österle and V. Bach (eds.) Customer Relationship Management in der Praxis: Erfolgreiche Wege zu Kundenzentrierten Lösungen [CRM in Practice: Successful Approaches of Customer-centric Solutions]. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Shahnam, E. (1999) The customer relationship management ecosystem. The Journal of Customer Loyalty 11: 22–29.

Payne, A. and Frow, P. (2005) Customer relationship management: From strategy to implementation, ANZMAC 2005 Conference: Business Interaction, Relationships and Networks. Perth, Australia: ANZMAC, p. 15.

Rigby, D.K., Reichheld, F.F. and Schefter, P. (2002) Avoid the four perils of CRM. Harvard Business Review 80: 101–107.

Winkelmann, P. (2002) Kundenbindung – richtig dosiert [Customer retention]. Marketing Journal 5: 41–45.

Salomann, H., Dous, M., Kolbe, L. and Brenner, W. (2005) Customer Relationship Management Survey: Status Quo and Future Challenges. St. Gallen, CH: Institute of Information Management, University of St. Gallen.

Webster, F.E. (1978) Is industrial marketing coming of age? In: T.V. Bonoma and G. Zaltman (eds.) Review of Marketing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, pp. 138–159.

Coviello, N.E. and Brodie, R.J. (2001) Contemporary marketing practices of consumer and business-to-business firms: How different are they? Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 16: 382–400.

Gummesson, E. (2004) Return on relationship (ROR): The value of relationship marketing and CRM in business-to-business contexts. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 19: 136–148.

Cohen, K.J. and Cyert, R.M. (1966) Theory of the Firm. Southern Economic Journal 32: 362–363.

Hatch, M.J. (1997) Organization Theory: Modern, Symbolic and Postmodern Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 15.

Bertalanffy, L. (1950) An outline of general systems theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 1: 139–164.

Senge, P. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday.

Normann, R. (1991) Service Management: Strategy and Leadership in Service Business. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 14–15.

Kühnapfel, J.B. (1995) Telekommunikations-Marketing: Design von Vermarktungskonzepten auf Basis des erweiterten Dienstleistungsmarketing. Wiesbaden, DE: Gabler.

Scheuch, F. (1989) Marketing. Munich, Germany: Vahlen.

Sasser, E.W., Olsen, P.R. and Wykoff, D.D. (1978) Management of Service Operations. Boston, MA: Alleyn & Bacon.

Levitt, T. (1972) Production-line approach to service. Harvard Business Review 50(September–October): 41–52.

Mack, O., Mayo, M.C. and Khare, A. (2005) A strategic approach for successful CRM: A European perspective. Problems and Perspectives in Management 2: 98–106.

Schmitt, B.H. (2003) Customer Experience Management: A Revolutionary Approach to Connecting with Your Customers. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Newell, F. (2003) Why CRM Does Not Work. Princeton, NJ: Bloomberg Press.

Auer, C. (2004) Performance Measurement für Customer Relationship Management: Controlling des IKT-basierten Kundenbeziehungsmanagement [Performance Management for IS-based CRM]. Wiesbaden, DE: Deutscher Unversitaets-Verlag.

Lecompte, M. and Goetz, J. (1982) Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research. Review of Educational Research 52: 31–60.

Hofstede, G. (2007) Cultural dimensions, http://www.geert-hofstede.com, accessed 13 April 2007.

Buttle, F. (2004) Customer Relationship Management: Concepts and Tools. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Ngai, E.W.T. (2005) Customer relationship management research (1992–2002). Marketing Intelligence & Planning 23: 582–605.

Parkinson, C.N. (1958) Parkinson's Law or the Pursuit of Progress. London: John Murray.

Whetten, D.A. (1989) What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review 14: 490–495.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, p. 56.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990, 1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Klein, H.K. and Myers, D.D. (1999) A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly 23(1): 67–94. Special Issue on Intensive Research.

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. and Lowe, A. (2002) Management Research: An Introduction. London: Sage Publications.

Guba, E.G. and Lincoln, Y.S. (2005) Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In: N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Dey, I. (1999) Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Glaser, B.G. (1978) Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press, p. 74.

Urquhart, C. (2001) An encounter with grounded theory: Tackling the practical and philosophical issues. In: E.M. Trauth (ed.) Qualitative Research in IS: Issues and Trends. London: Idea Group Publishing, p. 115.

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., Silverstein, M., Jacobson, I. and Fiksdahl-King, S.A. (1977) A Pattern Language – Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Koestler, A. (1975, c1967) The Ghost in the Machine. London: Pan Books.

OMG. (2003) Unified Modelling Language Specification, Version 1.5. Needham, MA: Object Management Group.

Wengraf, T. (2001) Qualitative Research Interviewing: Biographic Narrative and Semi-structured Methods. London: Sage Publications, pp. 61–93.

Silverman, D. (2000) Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. London: Sage Publications.

Glaser, B.G. (1992) Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs Forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press, p. 116.

Einstein, A. (1918) Principles of Research. Berlin, Germany: Max Planck Institut. Berlin, Physical Society.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1992) The balanced scorecard – Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 70 (January–February): 71–79.

Woodcock, N. (2000) Does how customers are managed impact on business performance? Interactive Marketing 1: 375–389.

Telemanagement Forum. (2001, 2005) Enhanced Telecom Operations Map (eTOM): The Business Process Framework for the Information and Communications Services Industry, GB921, V6.1. Morristown, NJ: TeleManagement Forum.

Lovelock, C. (1984, 2006) Services Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Homburg, C. and Sieben, F.G. (2001) Customer relationship management (CRM) – Strategische Ausrichtung statt IT-getriebenem Aktivismus [CRM – Strategic alignment instead of IT-driven short-term actions]. In: M. Bruhn and C. Homburg (eds.) Handbuch Kundenbindungsmanagement: Grundlagen – Konzepte – Erfahrungen [Handbook Customer Retention: Basics – Concepts – Experiences]. Wiesbaden, DE: Gabler.

Taxen, L. (2003) A Framework for the Coordination of Complex Systems’ Development. Linköping, Sweden: Department of Computer and Information Science, Linköpings universitet.

Whetten, D.A. (1989) What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review 14: 490–495.

Kleinke, C.L. (1984) Two models for conceptualizing the attitude-behavior relationship. Human Relations 37: 333–350.

Mcguire, W.J. (1969) The nature of attitude and attitude change. In: G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (eds.) The Handbook of Social Psychology. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Oskamp, S. (1977) Attitudes and Opinions. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Bem, D.J. (1972) Self-perception theory. In: L. Berkowitz (ed.) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press.

Einstein, A. (1954) Ideas and Opinions. New York: Random House, p. 28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Labus, M., Stone, M. The CRM behaviour theory – Managing corporate customer relationships in service industries. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 17, 155–173 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2010.17

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2010.17