Abstract

The salesforce can be both a rich source of market intelligence and a key vehicle for implementing marketing strategy. Historically, in many organisations, the sales function operated in tactical isolation from marketing strategy. Increasingly, companies are exploring the advantages of integrating sales with marketing, an approach which has been positively linked with improvements in business performance. This study explores a specific aspect of the connection between sales and marketing integration and better performance; specifically whether the integration of the sales and marketing functions in business-to-business (B2B) organisations facilitates the development and implementation of successful new strategies in response to market change. Based on a pilot survey, a model is proposed, placing sales and marketing integration, characterised by both interaction and collaboration between the two functions, as an antecedent for excellence in gathering market intelligence, and then using it to react strategically to changing market conditions and customer demands.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Organisations are under pressure to adapt to changing external circumstances so that they can survive and thrive in the long term. Those responding effectively to market turbulence are more likely to build competitive advantage over rivals who do not.1 Macro-environmental forces, including new opportunities, threats from competitors and changing customer expectations, are all beyond the control of managers, who as a result need to adapt their organisations quickly and smoothly to ensure continued prosperity. While organisations are under pressure to change, their salespeople are in turn under pressure to implement the necessary strategies in the marketplace to ensure these changes happen. Whilst these might only be relatively small changes to the marketing mix, they could also be more significant, such as entering a new market, launching a new product or adopting a new distribution channel. Such action might be required in response to external change, but may also be internally driven in order simply to improve effectiveness.1 Rackham and DeVincentis2 note that sales departments need to be adaptable and change-ready so that they can respond to both organisational dynamics and market dynamics. The sales function is a critical link between these two forces.

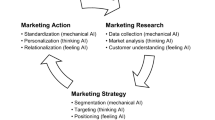

The salesforce is instrumental in both the formation and implementation of strategic plans.3, 4 Through their connection with the market, they are most aware of new developments from competitors and changing customer needs. This information can be accumulated and analysed by the marketing function to develop appropriate strategic responses, which the sales function then needs to translate into action. The impact of this action will in turn be observed by the salesforce, who close the feedback loop within the organisation by reporting the impact of the new plan's implementation. Over time, this cycle drives organisational change (Figure 1).

The marketing function will not be able to perform adequately unless it is sufficiently connected with what is happening in the marketplace. Homburg, Jensen and Krohmer5 noted that marketing departments sometimes have a low level of knowledge of the market and products, and that there is insufficient sharing of information between sales and marketing. So, if sales and marketing do not integrate adequately, they (and therefore the organisation as a whole) cannot observe and react to changes in the market. A high level of integration between marketing and sales could make the organisation very responsive to market dynamics.

The focus of this research lies where the rubber appears to meet the road: at the interface between sales and marketing. This exploratory research investigates whether increased sales and marketing integration results in organisations being better at gathering market intelligence and reacting to this by developing and implementing appropriate new strategies.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In their review of the literature on sales management and organisational change, Jones et al1 note that firms who respond effectively to market turbulence are more likely to build competitive advantage over rivals who do not. They identified a need to understand the salesforce's role in guiding organisational change efforts, and in turn how sales departments themselves are adapting to environmental changes.

Market-driven influences have been considered in other departments besides sales,6 but attention to the sales function and the important role that it plays both in informing and implementing marketing strategy is limited. Authors have identified the sales function as a valuable source of market intelligence,3, 7 but Le Bon and Merunka8 noted that few organisations fully leverage this potential. Salespeople that have built up good relationships with their customers are in pole position to learn about competitors’ products, pricing and projects, as well as customers’ new projects, long-term behaviour and preferences.8

The salesforce is an important component of the change process as it informs the organisation of external opportunities and threats. What appears not to have been fully considered is the efficacy of how this information is disseminated to the organisation: difficulties in mobilising the salesforce to engage in marketing intelligence,9 and adequately communicating gathered information to the organisation10 have long since been reported. The blame for this has largely been attributed to the salesforce. The question of how well market intelligence is received (or indeed solicited) by the organisation, as opposed only to how well it is transmitted by the salesforce, seems pertinent, yet overlooked.

Poor communication can lead to negative perceptions of the change process, as discussed by Kotter and Schlesinger11, 12 and Hultman.13 Introducing a change initiative results in consternation amongst employees due it its possible impacts on procedures, resource allocation and future exchanges.14 Communicating and justifying the change can be effective in increasing support for it.

Sales and marketing integration can be defined as ‘the extent to which the activities carried out by the two functions are supportive of each other’ and lead to the realisation of each others’ goals and objectives in a coordinated, synchronised or thoughtfully sequenced manner.15 Kahn and Mentzer16 identified three definitions of integration: interaction, where there is communication and information is exchanged between the two functions; collaboration, where resources are shared and cross-functional teams work towards shared goals, and; composite, which is a hybrid of the two. Genuine integration of sales and marketing can be distinguished from simple coexistence and communication.17

The integration of sales with marketing has recently been the subject of academic interest and calls for further research.18, 19, 20, 21 There is now some convincing empirical evidence that integrating sales and marketing positively affects business performance.22, 23, 24 Studies also confirm the practitioners’ expectations that integrating sales and marketing is not a straightforward thing for companies to achieve. Kotler et al17 opine that the main reasons why sales and marketing can’t just ‘get along’ are economic and cultural. In short, they argue that salespeople are doers and marketers are thinkers, and the two can often misunderstand and under-value each others’ contributions. The dangers of failure to integrate include marketing being out of touch with the market.5

This raises the question of where sales and marketing integration fits in with market-led organisational change. There appears not to be any explicit link previously made between integration of these two functions and improved strategic manoeuvrability in the face of market turbulence. Jones et al1 discussed the role of the salesforce in guiding organisational change efforts and adapting to environmental changes, and warned that conflict between sales and marketing could be a sign to managers that the implementation of new strategies might fail. This research aims to pull together these previously unconnected elements of the literature by focusing on the concept of organisational propensity to change. It is designed to explore whether improved integration of the sales and marketing functions enables organisations to be not only more sensitive to changes in the market, but also better at implementing appropriate strategic responses.

METHODOLOGY

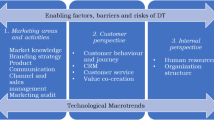

The main aim of this pilot study was to investigate whether sales and marketing integration affects corporate performance in the context of managing market-driven organisational change. Two constructs were formulated to measure this: the quality of actionable market intelligence gathered by the organisation (following Guenzi and Troilo22), and the capacity to implement appropriate strategic responses.

The sales and marketing integration construct needs to comprise interaction as well as collaboration (Kahn and Mentzer16) in order for organisations to achieve a good score on both constructs: interaction will result in successful sharing of information between the two functions, and therefore successful gathering of market intelligence. But without adequate collaboration, this could not result in successful implementation of a strategic response to this intelligence.

To structure this project, two hypotheses were formulated which could subsequently be tested. These were that:

Hypothesis 1:

-

The quality of actionable market intelligence gathered by the organisation will be higher if sales and marketing are more closely integrated.

Hypothesis 2:

-

Increased integration between sales and marketing results in organisations being more adaptable to market-driven change (i.e. their effectiveness in reacting by formulating strategic responses will increase).

The hypotheses were tested by examining the effect of sales and marketing integration (the independent variable) on two dependent variables: ‘market intelligence gathering’ and ‘strategic reactivity’. A cross-sectional, correlational study was chosen to gather the necessary data to measure each of these variables and test their effect on one another, with the aim of quantifying the strength and direction of the relationship between them. Depending on the normality of the data collected, either parametric or non-parametric statistical analyses could then be carried out to quantify the direction, strength and confidence limits of these two relationships.

The method was developed as a proxy measure of organisations’ propensity to change. This worked by leveraging the experience of a number of respondents from an executive background by asking them to provide their perspectives in the context of a change event that had occurred in their organisation. They were asked to relate this event to the market intelligence that may have driven it, and in turn were asked about the integration of their sales and marketing departments. This involved asking eight questions to measure market intelligence gathering and eight questions which measured strategic reactivity. An additional question measured both, making a total of nine indicators for each construct. The questions captured data on factors such as perceptions of quantity and usability of market intelligence provided by Sales, strategy-formulating ability, suitability of chosen responses, and finally satisfaction with strategy implementation speed, effectiveness and sustainability. The questionnaire was then pilot tested on a group of industry peers as part of the development process, before being administered.

By collecting multiple datasets, this method could describe and explain the relationship between sales and marketing integration with market intelligence gathering and strategic reactivity. A standard set of questions was posed to multiple respondents for gathering data on their own opinions and the attributes and behaviour of their organisations.

Sampling frame and sample size

The initial sampling frame was based on a purchased B2B database, as this would enable a large number of respondents to be contacted in a time-efficient way. A filtered mailing list of 1483 email addresses for contacts classed as ‘Senior Decision Makers’ from medium-sized UK-based B2B manufacturing companies was therefore purchased for the sampling frame. The identification and selection of respondents through the chosen sampling frame aimed to ensure they would fit the desired profile: senior personnel with a suitable background to ensure that they would be able to answer the questions with both accuracy and objectivity. Respondents therefore included Managing Directors, Chief Executives and managers or directors in charge of both Sales and Marketing. To further ensure the selection of respondents with the appropriate background in sales or marketing, and the appropriate senior level, filtering questions were used to qualify the knowledge of the respondents,25 these particularly focused identifying the job role of the individuals. In addition, descriptive data were collected for each sample by asking the number of staff in the whole organisation, and specifically how many in sales, and how many in marketing.

The response rate was very low, which is common in research involving sales management topics,26 and online surveys.27 This research was undertaken during a very difficult period in the recent recession, when decision-makers had little time to spare. To counteract this, the researchers also advertised for additional respondents on ‘Linked In’ (an online industrial/business networking website), and invited alumni of a sales management course. A personalised covering letter, containing the link to the survey, was emailed to each contact, which has been found to increase response rates.28, 29 Since these supplementary sources added an element of convenience sampling, a non-parametric analysis of the data was undertaken. At least 30 responses were needed to give an adequate degree of confidence in the strength of the relationship,30 and 41 were gathered.

Survey design

No pre-existing scales to measure market intelligence gathering and strategic reactivity were found, so they were developed using the nine indicators discussed above.

Another scale measured the sales and marketing integration construct and was adapted from a questionnaire devised by Kotler et al.17 On each scale, questions were answered by marking a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. The reliability of these scales was tested before analysing the results to ensure that they were internally consistent and that each question on the scale was in fact measuring the same construct.

The survey was pretested, and reviewed by a number of individuals within the researchers’ networks, individuals selected either fit the same criteria required for the main sample, or were specialists in the field.31

The survey was read by 119 people and a total of 41 responses was obtained, equating to a completion rate of 34.5 per cent. The survey had been successful in sampling respondents of the desired professional background: of the 90 per cent of respondents who gave their job title, over 43 per cent were either top-level executives or else in charge of both sales and marketing. The remainder were in charge of either sales or marketing.

The results were checked and processed using PASW Statistics 18 software. The data were tested for normality and considered fit for parametric analysis of the variables. This correlated the variables of sales and marketing integration and market intelligence gathering, and sales and marketing integration and strategic reactivity, quantifying the strength and direction of the two relationships.

RESULTS

The relationships between sales and marketing integration and market intelligence gathering, and sales and marketing integration and strategic reactivity, were investigated using Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient. Before performing this calculation, scatter plots were drawn (see Figure 2) and the correlations were first visually inspected to ensure that there was no violation of the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasiticity, which are necessary conditions for parametric analysis. Due to the limitations of the sample, which was not random, it was decided to run the parametric analysis anyway, and validate it by checking the results against a non-parametric correlational analysis.

Both scatter plots visually indicated a positive correlation, with a stronger relationship seen between sales and marketing integration and market intelligence gathering. This was confirmed when calculating Pearson's correlation (r) and the coefficient of determination (r2) for both relationships.

For sales and marketing integration and market intelligence gathering:

For sales and marketing integration and strategic reactivity:

According to Cohen,32 the r and r2 values for both relationships indicated that the association between the variables was large. For market intelligence gathering, 66 per cent of the variance in scores is accounted for by regression upon sales and marketing integration, and for strategic reactivity, 53 per cent is accounted for by the same. For both correlations, SPSS calculated statistical significance to the level of 0.01, which equates to a 99 per cent confidence level. A tabulated summary of the results generated in SPSS is shown in Table 1.

The Pearson's Correlation Coefficients were verified by Spearman's Rho test, a non-parametric technique for correlating datasets that do not have a normal distribution.

For sales and marketing integration and market intelligence gathering:

For sales and marketing integration and strategic reactivity:

These values support the Pearson's Correlation Coefficient results. Further support of these results is shown graphically in Figure 3, where it can be seen that scores on all three variables decrease as organisation size increases, indicating that there is a close association between them.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

These exploratory findings suggest that the hypotheses of this research are worthy of further investigation:

-

1

Organisations that have highly integrated Sales and Marketing departments are able to gather better quality market intelligence than those who do not.

-

2

Organisations with highly integrated Sales and Marketing departments will be better at reacting to market dynamics by formulating and implementing effective strategic responses compared with those that do not.

The findings also support the indications from the literature that communication is a component of interdepartmental interaction,16, 22, 24 as 66 per cent of the variance in ‘market intelligence gathering’ is explained by ‘sales and marketing integration’.

Interaction and collaboration are both components of interdepartmental integration,16 and there are questions that measure for both of these constructs on the scale for ‘strategic reactivity’. Because high scores on these questions contribute towards a high score for strategic reactivity, this suggests interaction and collaboration are necessary conditions for effective strategic response to market dynamics, but neither alone are sufficient conditions. This concept is summarised graphically in Figure 4.

An organisation's propensity to change effectively in response to market dynamics is affected by the combination of its ability to gather market intelligence and react to this by formulating and implementing appropriate strategies. Optimal market intelligence gathering is dependent on interaction between sales and marketing, whilst optimal strategic reactivity requires both interaction and collaboration. These two components form the construct of sales and marketing integration, hence the finding that sales and marketing integration contributes towards successful implementation of strategic changes in response to market dynamics.

It is interesting to note that smaller organisations exhibit a higher degree of sales and marketing integration, market intelligence gathering and strategic reactivity than large ones (see Figure 4), supporting the view of Kotler et al17 that integration between sales and marketing becomes an issue as companies grow. It has long been known that larger organisations have a higher degree of inertia than smaller ones when it comes to change implementation.33 In smaller organisations interaction would be easier and simpler as there are fewer people involved and they would typically work in closer physical proximity to each other. Having fewer people involved in the decision-making and implementation processes would also increase reactivity in terms of strategy implementation, as inertia is reduced. Nevertheless, since this research was exploratory, we can only conclude that the hypothesis that larger organisations have a lower propensity to change in response to market dynamics than smaller ones deserves further investigation.

Since propensity to change in response to market dynamics is an aspect of superior company performance, these exploratory findings are consistent with Le Meunier-FitzHugh and Piercy24 and add some weight to Jones et al's1 call for further research in the role of sales in company's strategic responsiveness. We infer that better integration between sales and marketing will make the process of change implementation easier.

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

It is often said that the pace of change in markets is accelerating, and that it is only the companies that keep close to their markets in order to anticipate and respond to change who will survive in the long-run. Many companies invest in market research as a key input their customer relationship management systems. In business-to-business sectors, categorised by more complex organisational customers and often by complex solutions, the relationship between salespeople at the customer interface and marketing colleagues creating a brand positioning for a company should intuitively be close. The management effort to facilitate integration between sales and marketing should not be under-estimated. There are historical precedents for sales and marketing departments in conflict, and it is the responsibility of senior management to create the right climate and organisational framework for close working relationships between sales and marketing that will improve the company's overall ability to react strategically and in good time to the demands of its markets.

LIMITATIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

A relatively small (n=41) convenience sample of organisations, mostly small/medium sized firms from the UK manufacturing sector, was analysed, which means that these findings cannot be generalised. The low rates response and completion may be attributable to a number of issues, including poor timing in the economic cycle, questionnaire fatigue, and the generally low response rates for sales management studies (as discussed). Furthermore, some of the companies sampled even had a policy on non-participation in research. It is also feasible that lack of interest in this survey may reflect that fact that few practitioners may understand the relevance or importance of this integration, which would be a cause for concern. Whilst there are limitations to this research, it is difficult to imagine a substantively interesting organisational analysis that is not potentially compromised.34

Longitudinal research could also be used to test whether sales and marketing integration affects the sustainability of change implementation. Buchanan et al's35 managerial, cultural and political factors have been linked with interdepartmental relationships: the strength of these has been proved to have a positive effect on organisational propensity to change, but it must also be understood to what extent this affects the sustainability of change post-implementation.

References

Jones, E., Brown, S.P., Zoltners, A.A. and Weitz, B.A. (2005) The changing environment of selling and sales management. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 25 (2): 105–111.

Rackham, N. and DeVincentis, J. (1999) Rethinking the Sales Force: Redefining Selling to Create and Capture Customer Value. UK: McGraw-Hill.

Piercy, N.F. and Lane, N. (2005) Strategic imperatives for transformation in the conventional sales organization. Journal of Change Management 5: 249–266.

Rogers, B. (2007) Rethinking Sales Management. Chichester: Wiley.

Homburg, C., Jensen, O. and Krohmer, H. (2008) Configurations of marketing and sales: A taxonomy. Journal of Marketing 72 (2): 133–154.

Hutt, M.D. and Speh, T.W. (1984) The marketing strategy center: Diagnosing the industrial marketer's interdisciplinary role. Journal of Marketing 48 (4): 53–61.

Webster, F. (1965) The industrial salesman as a source of market information. Business Horizons 8 (1): 77–82.

Le Bon, J. and Merunka, D. (2006) The impact of individual and managerial factors on salespeople's contribution to marketing intelligence activities. International Journal of Research in Marketing 23: 395–408.

Goodman, C. (1971) Management of the Personal Selling Function. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston.

Albaum, G. (1964) Horizontal information flow: An exploratory study. Journal of the Academy of Management 7 (March): 21–33.

Kotter, J.P. and Schlesinger, L.A. (1979) Choosing strategies for change. Harvard Business Review 57 (2): 106–114.

Kotter, J.P. and Schlesinger, L.A. (2008) Choosing strategies for change. Harvard Business Review 86 (7/8): 130–139.

Hultman, K.E. (1995) Scaling the wall of resistance. Training and Development 49 (10): 15–18.

Self, D.R., Armenakis, A.A. and Schraeder, M. (2007) Organizational change, content, process and context: A simultaneous analysis of employee reactions. Journal of Change Management 7 (2): 211–229.

Rouziès, D., Anderson, E., Kohli, A.K., Michaels, R.E., Weitz, B.A. and Zoltners, A.A. (2005) Sales and marketing integration: A proposed framework. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 25 (2): 113–122.

Kahn, K.B. and Mentzer, J.T. (1998) Marketing's integration with other departments. Journal of Business Research 42 (1): 53–62.

Kotler, P., Rackham, N. and Krishnaswamy, S. (2006) Ending the war between sales and marketing. Harvard Business Review 84 (7/8): 68–78.

Dewsnap, B. and Jobber, D. (2000) The sales–marketing interface in consumer packaged-goods companies: A conceptual framework. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 20 (2): 109–119.

Shapiro, B. (2002, October 28) Want a happy customer? Coordinate sales and marketing. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge. http://hbswk.hbs.edu/pubitem.jhtml?id=3154&sid=0&pid=0&t=customer, accessed 3 February 2010.

Rouziès, D. (2004) Observatoire de la Relation Marketing-commercial [Special Report by the Center for the Study of Sales and Marketing Relationships]. White paper, ADETEM, BT-Syntegra, HEC-Paris, Microsoft and Novamétrie.

Piercy, N.F. (2006) The strategic sales organisation. Marketing Review 6 (1): 3–28.

Guenzi, P. and Troilo, G. (2006) Developing marketing capabilities for customer value creating through Marketing-Sales integration. Industrial Marketing Management 35: 974–988.

Miller, T.G. and Gist, E.P. (2003) Selling in Turbulent Times. New York: Accenture-Economist Intelligence Unit.

Le Meunier-FitzHugh, K. and Piercy, N.F. (2007) Does collaboration between sales and marketing affect business performance? Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 27 (3): 207–220.

Gallup, G. (1947) The quintadimensional plan of question design. Public Opinion Quarterly 11 (3): 385–393.

Carter, R.E., Dixon, A.L. and Moncrief, W.C. (2008) The complexities of sales and sales management research: A historical analysis from 1990 to 2005. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 28 (4): 430–419.

Manfreda, K.L., Bosnjak, M., Berzelak, J., Haas, I. and Vehovar, V. (2008) Web surveys versus other survey modes. International Journal of Market Research 50 (1): 79–104.

Heerwegh, D. and Loosveldt, G. (2006) Personalising e-mail contacts: Its influence on web survey response rate and social desirability response bias. International Journal of Public Opinion 19 (2): 258–268.

Singh, A., Taneja, A. and Mangalaraj, G. (2009) Creating online surveys: Some wisdom from the trenches tutorial. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 52 (2): 197–212.

Stutely, M. (2003) Numbers Guide: The Essentials of Business Numeracy. London: Bloomberg Press.

Moser, C.A. and Kalton, G. (1971) Survey Methods in Social Investigation, 2nd edn. London: Heinemann.

Cohen, J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hannan, M.T. and Freeman, J. (1984) Structural inertia and organisational change. American Sociological Review 49 (2): 149–164.

Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Leiter, J. and Thompson, S. (1994) Organisation survey nonresponse. Administrative Science Quarterly 39 (3): 439–457.

Buchanan, D. et al (2005) No going back: A review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. International Journal of Management Reviews 7 (3): 189–205.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lyus, D., Rogers, B. & Simms, C. The role of sales and marketing integration in improving strategic responsiveness to market change. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 18, 39–49 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.5

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2011.5