Abstract

Managers, consultants and scholars alike consider the digital customer experience (CX) as the next competitive battleground for firms worldwide. The development of corresponding CX strategies, however, faces a number of challenges. First, similar to all emerging fields of management, there is no universally accepted definition of the concept, its scope and how it relates to associated management initiatives, such as quality and satisfaction. Second, it is widely accepted that CX is very context-specific and that there is unlikely to be a generally applicable ‘play book’ appropriate across all industries and company strategies. Scholars portray CX disparately by exploring important facets at, regrettably, high levels of abstraction. Therefore, their research fails to consider the vital role of management in the process. In spite of a plethora of published CX definitions and conceptual frameworks, there remains a need for both theoretical and conceptual development, and empirical research to determine which digital CX strategies and practices have the most positive influence on organizational performance. To contribute to the development of CX practice and what the author characterizes as a Theory of Relevance, this article argues that scholars must conduct research to reveal current CX management practices as a necessary foundation for providing direction. A typology of CX practice will act as the foundation to explore the link between practice and performance. This study uses this typology to highlight the superior performance of firms executing a value-driven digital customer experience strategy. These vanguards, unlike others, apply value creation to all stakeholders of their business. Their business practice reflects these principles by developing a strategy crossing departmental boundaries and integrating all of the firm’s functions into one aim — delivering superior digital customer experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Customer experience (CX) management and CX strategy are very important areas of research, in which ‘practice’ is in many ways ahead of ‘academia’.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 However, it appears that there is no clear consensus yet on how CX research, in particular in the digital marketing context, can be instrumental in increasing the practical relevance of marketing scholars’ research.6

One way to achieve this is by developing a Theory of Relevance. The term relevance refers to relevance to practice and for practitioners. I posit that CX research has to provide more than prescriptive and descriptive guidance. It needs to go a step further and address how business problems should be solved and advise on how things should be done in practice.7 In a recent conference paper,8 marketing scholars adapted a taxonomy of theory9 to classify research articles appearing in leading marketing journals. They concluded that more than 90 per cent of all research papers focus on description, explanation and prediction theory, while less than 10 per cent go beyond description and develop specific design and action theory. Design and action theory develops general principles to solve a category of business problems, rather than a unique set of features aimed to solve a unique business problem (eg, a specific offering from a specific provider and/or in a specific context/setting). It is important to note that the level of generalization clearly distinguishes this approach from consultancy practices.

This study extends prior CX research by connecting a typology of customer experience practices to firm performance and subsequently developing principles about how to solve the business problem of creating successful digital CX management programmes. It illustrates the effectiveness of the most profitable strategies relating to the organization’s practices.

The article is organized as follows. First, it summarizes the existing CX literature, leading to a call for the development of a Theory of Relevance. Then I introduce and elaborate upon the CX typology adopted for the study. After introducing the method, the findings are presented and discussed with the implications for theory and practice. Finally, I share the study’s limitations, leading to the opportunities for future research.

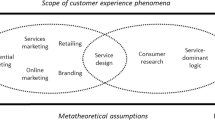

CX research has a long history, despite only recently becoming en vogue, going back as far as the early nineteenth century.10 Back then, scholars were already discussing the concept of customer experience centrality, identifying strategies revolving around CX as the only viable exchange paradigm.11 Provocatively speaking, one could argue that today’s holistic conceptualizations and definitions of CX from both scholars and businesses provide very little additional insight beyond how the phenomenon was described in the past. While more recent definitions of CX remain very broad — ranging from a customer’s actual and anticipated purchase and consumption experience,12 a distinctive economic offering,13 or the result of encountering, undergoing or living through events, to the notion of the new, experience-seeking consumer14 as a co-creator of value15 — two main themes emerge. First, CX is holistic and, second, it includes process and outcome components. Compared with early CX literature, stating that people do not desire products and services but the experiences these offerings will deliver, one can conclude that very little progress in exploring the phenomenon has been made. If this is indeed the case, one has to ask why this might be.

One possible explanation is that marketing as a science has certain strengths and areas of potential for improvement. To illustrate this, allow me to simplify and state that (the solving of) business problems can be divided into three stages. The first stage is to explore and determine which requirements are needed to solve the problem. The second stage — let us call it the ‘black box’ — includes processes, actions and interactions leading to the third, and final, stage — linking the results of these actions to outcomes.

Marketing scholars traditionally excel in Stage 1, determining the requirements needed for a specific action to solve a business problem, and Stage 3, connecting the actions to an outcome. The latter is achieved by, for example, measuring the action’s impact upon customer satisfaction, service quality and so on. However, scholars are struggling to gain significant insight into Stage 2, to decode what happens inside the black box. Given CX’s complex, multifaceted and holistic nature, this task becomes not only more important, but also more challenging.

Another possible explanation for this gap is the sometimes-stated lack of relevance in marketing scholars’ research. Marketing is, fundamentally, about application. Therefore, the academic community should seek to provide both guidance and solutions to practitioners. According to meta-theorists, such as Dickhoff et al,16 marketing research and theory must have an action orientation because it exists ‘finally for the sake of practice’.

This study delivers a contribution to both practice and the Theory of Relevance, extending an existing typology of customer experience practices into the digital marketing context. It presents an analysis of — and connection between — digital CX practices and firm performance. This allows the development of principles about how to solve the business problem of creating successful digital CX management programmes.

The challenge of customer experience practice

The challenge of understanding and creating the most profitable customer experiences strategies and corresponding practices sits atop most chief executives’ agendas. Companies such as Ritz Carlton, Disney, IKEA, Singapore Airlines and Apple revolve their management strategies around developing favourable customer experiences. Only a few scholarly studies focus on how to manage CX in practice, however, and there are few discussions on company strategy for designing and managing favourable CX. Given the increasing importance of digital channels for customers worldwide, digital CX strategies are becoming even more relevant. This added component, however, adds yet another level of complexity to designing favourable customer experiences.

The level of complexity does not stop here, though. Berry, Carbone and Haeckel15 argue that organizations should recognize CX clues related to both functionality and emotions. Since emotions play an important role in how customers perceive their experience, offers must be designed to ensure that both functional and affective aspects are considered carefully. However, there is no clear consensus on how these two aspects contribute to CX. This review on the emerging challenges highlights that we are still struggling to define the construct coherently. By connecting practices to performance, this study adds a much-needed viewpoint to this discussion. On the basis of its findings, I develop a set of principles to provide guidance on how CX management should be practised. Klaus et al17 define CX management as ‘a strategic approach to designing experiences in order to create value for both customers and the organization’.

Preservers, Transformers and Vanguards — A typology for CX strategy and management

Implementing CX is challenging because of its broad definition and scope. CX covers an extended time horizon for every customer, direct and indirect, and every touch-point, as well as emotional and functional responses. To deal with this challenge, organizations need to define a clear scope commensurate with their strategies and then determine an achievable plan for its development. Given the contextual nature of CX, it is not likely that scholars will develop a comprehensive and universal guide to CX implementation quickly, or that consultants will find it easy to develop a universal best practice to avoid the risk of CX implementation failure.

In brief sections on managerial implications in most studies, scholars exhort managers to do everything with the unchallenged assumption that only the truly committed and ambitious succeed. However, a large-scale, comprehensive CX programme may not only be beyond the immediate reach of most firms, it may also not be universally desirable (eg, for budget airlines). A typology of CX practice allows managers to define their level of ambition, scope their efforts and allocate their investments accordingly. A typology of CX management is proposed here as a starting point for firms seeking to both understand the quality of practice and systematically plan for CX development.

This study adopts Klaus et al’17 CX strategy and management practice typology. Klaus et al17 divide existing CX management practices into three clusters: Preservers, Transformers and Vanguards. The practices of these clusters differ over the five dimensions of CX strategy and management, namely, definitions, scope and objectives; governance; management; policy development; and challenges (see Table 1). Klaus et al17 describe the clusters as shown in Table 2.

Preservers

Preservers define CX management as an extension or development of existing service delivery practices and assess effectiveness using traditional customer outcome measures of service quality or satisfaction. While acknowledging its importance, Preservers are incapable of making a strong business case for CX to top management. For example, the manager of a financial service firm states that they ‘do not know how CX relates to business outcomes’.

Preservers’ programmes are a series of limited initiatives, rather than a comprehensive programme led by a well-articulated long-term vision. Their practices lack central control, corresponding processes or an overarching vision. Inabilities to connect CX management practice to identifiable goals and outcomes prevent the development of a compelling business case and elevation of CX to a strategic level. Preservers provide few examples of positive and negative CX and have little knowledge of their programmes’ origin. While they acknowledge the importance of accountability, they struggle to develop appropriate measures of effectiveness.

Their focus is on organizational results, whereas outcomes for employees, customers and corresponding core business processes, such as front and back office integration, are not developed. Preservers provide limited training for customer-interacting employees responsible for delivering good experiences. Preservers acknowledge neither the importance of digital channels nor their influence on CX. Preservers do not discuss the role of business partners in delivering experiences. Although they acknowledge verbally the importance of CX management, they do not develop commensurate practices.

Transformers

Transformers differ from Preservers in all five dimensions of CX practice. Transformers believe CX is linked positively to financial performance, but acknowledge its holistic nature and the resulting challenges in scoping and defining CX and CX management. This indicates a clear internal discourse concerning CX strategy and its management practice.

Unlike Preservers, Transformers view all channels — digital in particular — as a key component for shaping their programmes. As the manager of a retail conglomerate states, ‘we know that all channels influence our customers’ behaviour’. Transformers are convinced that CX influences customer satisfaction, loyalty, recommendation and brand perception. In contrast to Preservers, who manage it as an extension of existing practices, Transformers believe CX is strategically important and highlight the necessity of designing and executing a corresponding strategy based on the organization’s definition of CX.

Transformers connect CX practice to organizational goals and link practice to existing measurements of customer outcomes. However, Transformers acknowledge shortcomings of existing measurements and search for more sophisticated approaches to assess CX and its performance impact. Transformers articulate a detailed history of their programmes, most often initiated by a top executive. All Transformer organizations have CX teams with individuals assigned purely to this task. These individuals do not necessarily constitute a central and cross-departmental team. Transformers acknowledge the impact of customer-interacting personnel on delivering CX and influencing customer behaviour and develop appropriate training programmes.

In comparison to a Preserver’s focus on incremental improvements, Transformers strive to become a CX-focused organization, acknowledging both the broad nature of CX and implications for managing CX throughout the organization. These organizations accept long-term commitment to transformation. Nonetheless, they struggle to develop a CX business model and corresponding business processes. While they often concentrate on improving existing processes, they struggle to grasp the overall picture of CX strategy. While Transformers struggle to link CX to financial outcomes, they are convinced of the positive influence of CX on customer behaviour and their organizational goals.

Vanguards

Vanguards have a clear strategic model of CX management impacting all areas of the organization, and develop commensurate business processes and practices to ensure its effective implementation. While Transformers merely acknowledge the broad-based challenges of CX management, Vanguards integrate functions and customer touch-points to ensure consistency of the desired customer experiences across their own business and those of their partners. Digital channels and an integrated digital CX programme are essential to this approach. The CEO of a telecommunication provider acknowledges that ‘digital has become the most crucial of our channels in terms of driving consumer behaviour’.

Vanguards use existing measurements to track the impact of their programmes based on customer-centric outcomes and evaluations, while constantly developing new tools and practices to support the overall strategy. For example, Vanguards recognize the crucial role of accountability and are constantly developing new and better ways to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of CX practice. Vanguards manage the design and measurement of experiences through a central group that integrates multiple organizational functions. CX practice is founded on the conviction that satisfying expected outcomes for customers is the driver of organizational performance. Training, recruitment and human resources development are guided by the CX strategy. Thus, employees are rewarded for delivering experiences that customers value.

In Vanguard organizations, management receives clear and visible support from top executives. Practice continually develops the CX business model. This model is based on — and implemented by — internal research and functions throughout the entire organization. Vanguards develop evidence to monitor and assess the effectiveness of the experience strategy based on measurements of loyalty and customer satisfaction.

To extend and expand our knowledge about CX strategy and management practices, I decided to explore the suggested relationship between CX practices and profitability in more detail. I decided that the study should include more than one type of context in order to develop a set of practices for a wide range of organizations.

Methodology

On the basis of the typology,17 I created a survey to articulate the meaning and domain of digital CX strategy and management practice using expert informants. I identified potential experts for the study by following the procedure advocated by the literature18 based on the following criteria:

-

a)

tangible evidence of expertise,

-

b)

reputation,

-

c)

availability and willingness to participate,

-

d)

understanding of the general problem area,

-

e)

impartiality,

-

f)

lack of an economic or personal stake in the potential findings.

Managers were then further selected based on meeting the following three criteria:

-

(g) employed with a company at least since the introduction of the digital CX programme,

-

(h) involved with the programme’s creation and introduction,

-

(i) responsible for current digital CX management and programme development.

This selection procedure ensured the reduction of bias.19 We conducted surveys with 80 managers meeting the selection criteria.

In a subsequent step, after allocating all cases to their respective clusters — Preservers, Transformers and Vanguards — three researchers scrutinized the individual, self-reported sales growth numbers of all cases over the last 3 and 5 years. This analysis allows the exploration of the crucial link between CX strategy and management practices and profitability, following the guidelines of well-established studies exploring marketing practices.20

Findings

After clustering the individual cases, we calculated their average profitability, measured by their self-reported sales growth over the last 3 and 5 years. Preservers had the lowest average profitability (1.1 per cent), while Vanguards reported by far the highest average (8.2 per cent), almost double the Transformers’ score (4.2 per cent). This finding has wide-ranging implications for both theory and practice.

Discussion

This research not only validates the Klaus et al17 CX strategy and management practice typology, but, more importantly, connects digital CX practices to profitability. The typology helps firms to scope ambition and establish a realistic development path for investment in new experience-creating capabilities, such as the use of digital channels to design favourable customer experiences.

Despite encouragement from scholars and consultants for radical transformations of experience management, organizations must first establish the extent of their ambitions and practices. Next, they can evaluate how they relate to an overall strategy, determining the contribution of the digital CX in detail. For some companies, a limited commitment to experience may be sufficient to retain customers and achieve marketing objectives; others may wish to compete on superior experience and will need to develop from an emergent to a competitive programme.

This study allows managers to determine their current state of practice and to contemplate whether and how their practices differ from the most profitable ones in their industry. Therefore, this study, in combination with the existing typology, gives managers not only an opportunity to benchmark their existing practices, but a foundation for improving their CX strategy and management programme across all dimensions of their practice: CX definitions, scope and objectives; governance; management; policy development; and challenges.21

CX strategies and value co-creation

Scholars22 highlight the connection between CX strategy and management practices and firm performance based on value co-creation. Scrutinizing the practices of the most profitable firms, the Vanguards, my study supports this assertion. Vanguards, unlike other existing practices, extend CX management skills, such as co-creation, not only to customers, but also to the firm’s broader network. Internally, their reward structures match CX objectives, focusing on customer assessment of the experience.

When the programme extends to suppliers, the firm assesses and rewards them against measures of CX. Vanguards’ digital practices and strategies are based on the principle of resource integration. This integration forms a prerequisite for customers’ value co-creation where value is understood as experiential, contextual and meaning-laden23. Vanguards verify the use of customers as an operant resource in terms of, for example, customer insights, using opinions or feedback from customers to create new value propositions.

Vanguards involve customers in value creation in various ways, but in particular through the use of digital communication platforms. For example, customers assist in the design and development of the service system, achieved through feedback from complaints, suggestions or contributions delivered through user platforms. Other tools and techniques used include social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, to drive an open two-way communication that drives and guides the design and development of mutually beneficial CX management practice.

Towards a Theory of Relevance

The aim of my study is to contribute to a Theory of Relevance by developing principles for solving the business problem of creating successful CX strategies and management programmes. This is achieved by extending the work of Klaus, Edvardsson and Maklan,17 connecting their typology of customer experience practices to firm performance. By connecting CX practices to profitability, my study goes beyond description and develops specific design and action theory. It develops general principles to solve a category of business problems, designing profitable CX strategies and management practices, rather than a unique set of features aimed to solve a unique business problem.

However, this is just a start, and I hope this example demonstrates how we, as scholars, can develop theory that is highly relevant to practice. In fact, my colleagues and I are convinced that CX strategy and management — in particular the digital CX — delivers an ideal platform to achieve this. CX does not live in a functional area, and practical solutions are needed to address the difficulties and opportunities on a strategic level. CX allows us not only to create a set of tools that shape practice and the conversation, but also to train future managers and shift their thinking, emphasizing the strategic level of CX management.24

I posit that marketing should own both customer experience and customer relationship management.25 Thus, marketing practitioners and scholars will lead the strategic agenda to influence and guide how relationships are built and influenced. In summary, (digital) CX allows us as scholars not only to challenge but also to change the way to think and ultimately conduct business, by developing a Theory of Relevance.

Limitations and future research directions

This study explores the link between digital CX strategies and profitability using an existing typology that is applicable across varying service settings and contexts. Different sectors face disparate issues, and therefore we encourage researchers to test empirically the findings by studying various practices. These studies could provide insight into whether and to what extent our findings differ across contexts and sectors, for example, between goods and service contexts and sectors. The challenge and research opportunity is to use the typology to build the road from moving towards becoming a Vanguard into a practical setting to analyse strengths and weaknesses. I posit that the five dimensions of CX practice are interdependent, but deriving the nature of interconnectivity requires further investigation. Another stream of investigation would be to explore the primary drivers behind CX strategies resulting in favourable or unfavourable CX. Finally, I suggest studies in which firms with the same or similar CX strategies in select industries are compared based on CX outcomes. Studies should identify and analyse the mechanisms behind these differences and explore communication and implementation of CX strategies.

References

Klaus, P. (2013) ‘The case of Amazon.com: Towards a conceptual framework of online customer service experience (OCSE) using Emerging Consensus Technique (ECT)’, Journal of Services Marketing. Vol. 27, No. 6, pp. 443–457.

Klaus, P. and Maklan, S. (2012) ‘EXQ: A multiple-item scale for assessing service experience’, Journal of Service Management. Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 5–33.

Klaus, P. and Maklan, S. (2013) ‘Towards a better measure of customer experience’, International Journal of Market Research. Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 227–246.

Klaus, P. (2013) ‘New insights from practice — Exploring online channel management strategies and the use of social media as a market research tool’, International Journal of Market Research. Vol. 55, No. 6, pp. 829–850.

Klaus, P. and Ngyuen, B. (2013) ‘Exploring the role of the online customer experience in the firms multi-channel strategy — An empirical analysis of the retail banking services sector’, Journal of Strategic Marketing. Vol. 2, No. 5, pp. 429–442.

Klaus, P., Gorgoglione, M., Pannelio, U., Buonamassa, D. and Nguyen, B. (2013) ‘Are you providing the ‘right’ experiences? The case of Banca Popolare di Bari’, International Journal of Bank Marketing. Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 506–528.

Keating, B., Gregor, S. and Theodoulidis, B. (2013) in Proceedings of the 2nd Cambridge Academic Design Management Conference, 4–5 September, IFM, Cambridge.

Gregor, S. (2006) ‘The nature of theory in information systems’, MIS Quarterly. Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 611–642.

Bastiat, F. (1848) Selected Essays on Political Economy. Cairns, S (trans), de Huszar (eds) Van Nostrand, Irvington-on-Hudson, NY.

Head, J. (1872) Retail Traders and Co-Operative Stores. H.G. Reid, Steam Print Works, Middlesbrough.

Abbott, L. (1955) Quality and Competition: An Essay in Economic Theory. Columbia University Press, New York.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C. and Lehmann, D. R. (1994) ‘Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden’, Journal of Marketing. Vol. 58, No. 3, pp. 53–66.

Arussy, L. (2002) ‘Don’t take calls, make contact’, Harvard Business Review. Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 16–18.

Cova, B. (1996) ‘What postmodernism means to marketing managers’, European Management Journal. Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 494–499.

Berry, L. L., Carbone, L. P. and Haeckel, S. H. (2002) ‘Managing the total customer experience’, MIT Sloan Management Review. Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 85–89.

Dickhoff, J., James, P. and Wiedenbach, E. (1968) ‘Theory in a practice discipline. Part 1: Practice oriented theory’, Nursing Research. Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 415–435.

Klaus, P., Edvardsson, B. and Maklan, S. (2012) Developing a typology of customer experience management practice – From Preservers to Vanguards. 12th International Research Conference in Service Management, La Londe les Maures, France, May/June. Available at http://goo.gl/yxJOCE.

Hora, S. C. and Von Winterfeldt, D. (1997) ‘Natural waste and future societies: A deep look into the future’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Vol. 56, No. 2, pp. 155–170.

Adelman, L. and Bresnick, T. (1992) ‘Examining the effect of information sequence on patriot Air Defence officer judgements’, Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes. Vol. 53, No. November, pp. 204–228.

Coviello, N. E., Brodie, R. J., Danaher, P. J. and Johnston, W. J. (2002) ‘How firms relate to their markets: An empirical examination of contemporary marketing practices’, Journal of Marketing. Vol. 66, No. 3, pp. 33–46.

Klaus, P. (2014) Measuring Customer Experience — How to Develop and Execute the Most Profitable Customer Experience Strategies. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Klaus, P., Gorgoglione, M., Pannelio, U., Buonamassa, D. and Nguyen, B. (2013) ‘Are you providing the ‘right’ experiences? The case of Banca Popolare di Bari’, International Journal of Bank Marketing. Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 506–528.

Vargo, S. L. and Lusch, R. F. (2008) ‘From goods to service(s): Divergences and convergences of logics’, Industrial Marketing Management. Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 254–259.

Klaus, P., Edvardsson, B., Keiningham, T. and Gruber, T. (2014) ‘Getting in with the "In" crowd: How to put marketing back on the CEO’s agenda’, Journal of Service Management. Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 195–212.

Klaus, P. (2014) ‘Preservers, transformers and vanguards: Measuring the profitability of Customer Experience (CX) strategies’, DMI Review, Design Management Institute Publications. Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 24–29.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klaus, P. Towards practical relevance — Delivering superior firm performance through digital customer experience strategies. J Direct Data Digit Mark Pract 15, 306–316 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2014.20

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2014.20