Abstract

This paper provides presidents and academic leadership with a body of literature that will strengthen the leaders’ understanding of the unique behaviors and characteristics that are paramount to successful fund raising in the academic arena. A better understanding of transformational, transactional, and transformative leadership theory, and the attributes that are associated with them, can not only help leaders shape and mold their approach to fund raising but also enable them to infuse a greater sense of meaning into their respective institutions while increasing the amount of financial support they garner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With characteristic bluntness, Upton Sinclair once remarked that the college president spends his time running back and forth between Mammon and God (Sinclair, 1923). Sinclair may have accurately described the nineteenth- and twentieth-century president, but twenty-first-century university and college presidents appear to be driven by mammon alone. Cook (1994) suggests that the role as fund raiser has become the most important one for university and college presidents.

More and more, the success of a university or a college depends on the president's ability to successfully integrate an effective leadership style with his/her fund-raising activities.

University and college presidents admit that their role is increasingly about mammon and that they are ultimately responsible and accountable for the bottom line of their university or college. Birnbaum (1989) concludes that university and college presidents, operating in complex, ambiguous settings, are asked to be all things to all people. While Birnbaum's conclusion may be true, for university and college presidents, the bottom line is, more often than not, fund raising.

The leadership and fund-raising theory outlined in this paper provides a framework for presidential and academic leaders that will help guide their approach to fund raising. By reviewing characteristics of top fund-raising presidents, academic leaders may benefit from examining these existing behaviors through a couple of questions:

-

1

To what extent do college and university presidents, who are highly successful fund raisers, exhibit transformational or transactional leadership behaviors and characteristics, and how are these behaviors and characteristics exercised in their fund-raising activities?

-

2

To what extent are transformative leadership behaviors and characteristics exhibited by college and university presidents who are identified by leaders in Advancement as highly successful fund raisers?

Transformational, transactional, and transformative leadership theoretical framework

According to Bornstein (2003), successful change in an institution of higher education is defined by four complex and interrelated factors: presidential leadership, governance, social capital, and fund raising. The first and last factors are the cornerstones of this study because they are considered the most important factors in any attempt to create change at institutions of higher learning. Birnbaum (1992) stated that studies of academic leadership have tended to focus on institutions as rational, goal-seeking organizations that emphasize the importance of leader characteristics and actions and describe what leaders should do to be effective. Although studies have examined academic leadership, the presidential role has lacked historical perspective and rigorous scientific inquiry (Cook and Lasher, 1996).

Prior to the introduction of charismatic-transformational leadership theories, most researchers referred to transactional contingent reinforcement as the core component of effective leadership behavior in organizations (Bass, 1985). Burns (1978) defines transactional leadership as the exchange of valued things, economic or political or psychological, between leaders and followers without a call to a greater purpose. In organizations with transactional leadership, followers agree with, accept, or comply with the leader in exchange for praise, rewards, and resources or in order to avoid disciplinary action.

In contrast to transactional leadership, transforming leadership introduces and advances new cultural forms. Transforming leadership is defined as “the engagement of people in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality” (Burns, 1978). The purposes of leaders and followers, which might have started out separate but related, become fused. Power bases are linked, not as counterweights, but as mutual support for common purposes. Although some researchers think that it is necessary for university and college presidents to be transformational leaders, Birnbaum (1992) asserts that good presidents are not purely transactional or transformational; instead, they synthesize the two approaches.

Transformational leadership

The components of transformational leadership have been identified in a variety of ways, including the use of factor analyses, observations, interviews, and descriptions of a person's ideal leader. Using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ-Form 5X), Avolio et al. (1999) identify four distinct components of transformational leadership (i.e., the four I's):

-

1

Idealized influence. Transformational leaders are admired, respected, and trusted. Followers identify with and want to emulate this type of leader. Transformational leaders produce these emotional reactions by considering the needs of their followers and trying to meet them. Transformational leaders share risks with their followers and always adhere to their personal ethics, principles, and values.

-

2

Inspirational motivation. Transformational leaders behave in ways that motivate those around them. This type of leader provides their followers with meaningful, challenging work. Individual and team spirit are aroused. Enthusiasm and optimism are displayed. The transformational leader encourages followers to envision attractive future states, which they can ultimately envision for themselves.

-

3

Intellectual stimulation. Transformational leaders stimulate innovation and creativity in their followers by questioning assumptions, reframing problems, and approaching old situations in new ways. Simic (1998) states that these leaders stimulate change in the way people think about problems: for example, they use metaphor and analogy to describe problems and solutions. Transformational leaders do not ridicule or publicly criticize individual member's mistakes. New ideas and creative solutions to problems are solicited from followers, who are included in the decision-making process.

-

4

Individualized consideration. Transformational leaders pay attention to each person's need for achievement and growth by acting as a coach or a mentor. Followers are helped to reach higher levels of achievement. New learning opportunities are created in a supportive climate. Transformational leaders recognize each person's needs and desires.

Some researchers believe that vision is the characteristic that ultimately differentiates a transformational leader from a transactional leader. According to Antonakis (2001), all transformational leaders have a vision of their institution's future, and they are expected to use the authority of their office to turn this vision into reality. It might be more appropriate to view a university or college president as a storyteller instead of a visionary. According to Birnbaum (2002), a good story, oft-repeated, can motivate a campus as it weaves together an institution's history and values with it future possibilities.

As Peters and Waterman (1982) state, a transforming leader builds on people's need for meaning and desire for leadership that creates institutional purpose. Gardner (1995) asserts that leadership occurs in the human mind: it is essentially a cognitive phenomenon. Transformational leaders convince others to share goals and meaning by telling good stories. They either devise their own stories or use stories that already exist in a culture, developing or revising them in some way.

According to Gardner (1997), a leader influences his or her followers in a set of cognitive exchanges: that is, in a meeting of the minds of the leader and his or her followers. The principal vehicle of influence is the story, and the most influential stories represent the leader's ethics, principles, and values. Pettigru (1976) agrees that a leader not only creates the rational and tangible aspects of organizations, such as structure and technology, but also creates the symbols, ideologies, beliefs, rituals, and myths that mark the future direction of the institution.

Transactional leadership

Clark (1992) suggests that transformational leaders are not chosen for successful institutions because “they are inappropriate for the stability, continuity, and maintenance of the existing power structure.” Transactional leaders are better suited for successful institutions that need to improve through incremental change instead of transforming change. Bass (1985) claims that transactional leadership is characterized by four behaviors:

-

1

Contingent reward. The transactional leader clarifies the work that must be accomplished and uses rewards or incentives to achieve results.

-

2

Passive management by exception. The transactional leader uses correction or punishment as a response to unacceptable performance or deviation from the accepted standards.

-

3

Active management by exception. The transactional leader actively monitors the work of his or her followers and uses corrective methods to ensure that the work meets accepted standards.

-

4

Lassez faire. Transactional leaders are indifferent and have a hands-off approach toward workers and their performance. The transactional leader ignores the needs of the others, does not respond to their problems, and does not monitor performance.

These characteristics of transactional leadership reveal that it functions more successfully in a mature, stable culture. Kuh and Whitt (1988) define culture in higher education as collective, mutually shaping patterns of norms, values, practices, beliefs, and assumptions that guide the behavior of individuals and groups in the institution and enable them to make meaning of events and actions on and off campus. Transactional leadership maintains a culture that already exists.

Transformative leadership

Munitz (1998) states that there is no single definition of leadership. There are different styles, settings, and contexts. Strong executives require courage, a willingness to take risks, an ability to dream about alternatives while weighing their consequences, and the capacity to engage colleagues toward common goals.

In a study conducted by Bornstein (2003), presidents were asked whether they were transformational (bold, visionary, inspirational) or transactional (collegial, interactive, collaborative). Fifty percent of the survey respondents considered themselves transformational, but of these, 71 percent said most presidents are transactional. In fact, only 28 percent of the respondents saw themselves as transactional. Interestingly enough, even though the question was not asked, 23 percent considered themselves both transformational and transactional.

Based on these findings, Bornstein (2003) proposes the term transformative leadership and defines it as the “exercise of either or both presidential authority and constituent, as appropriate to the situation” (p. 99). Transformative leadership is a more salutary concept than either transformational or transactional for a successful president who is promoting a change agenda. The use of the term transformative leadership is meant to suggest a continuum of behaviors available to all presidents.

Methodology

This study used quantitative methods to identify and more clearly define the leadership behaviors and characteristics of university and college presidents, and qualitative methods to discover how these behaviors and characteristics influence a president's fund-raising activities. This mixed method study was conducted using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), interviews, observations, and document reviews.

In quantitative research for this study, the university or college president, vice president, and major donor of each institution completed the Multifactor Research Questionnaire to evaluate how frequently, or to what degree, the university or college president engaged in 32 specific transformational and/or transactional behaviors and characteristics. This survey was administered to help provide an objective and a measurable assessment of the varying degrees that transformational and transactional leadership attributes may have on fund-raising activities.

In contrast, the qualitative research in this study was much more subjective than the quantitative one and the researcher used different methods of collecting information, mainly individual, in-depth interviews. The decision to use qualitative methods in this investigation stems, in part, from the limited number of studies that examine how leadership styles affect university and college presidents’ fund-raising activities.

The initial sample of presidents was drawn from an e-mail submitted to vice presidents of university advancement currently serving in Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) District III institutions of higher learning in the southeast part of the United States. The initial e-mail asked 1,007 vice presidents to nominate five university or college presidents who are successful fund raisers. Individuals serving as vice president were surveyed because they are leaders in advancement, and they are in the best position to nominate successful fund-raising presidents. Seventy-eight vice presidents for advancement responded to the survey and nominated 118 presidents. Of the 118 presidents described as successful fund raisers, 13 received four or more votes, and these presidents were considered the strongest candidates for inclusion in the study. Of these 13 presidents, four agreed to participate in the study. The candidates were contacted by (1) an initial phone call explaining the nature of the study and intent to invite the president to participate in the study and (2) an e-mail inviting the participant to be a part of the study. The e-mail included an official letter of introduction outlining what would be expected from each participant, a copy of the MLQ, and a set of sample interview questions.

The presidents, vice presidents, and major donors who participate in the study are

Dr. Rita Bornstein, President Emerita, Rollins College

Dr. Anne Kerr, Vice President

Mr. David Odahowski, Major Donor

Dr. John Casteen, President, University of Virginia

Mr. Robert Sweeney, Vice President

Mr. David Gibson, Major Donor

Dr. Gordon Gee, President, Vanderbilt University

Mr. Robert Early, Vice President

Mr. John Ingram, Major Donor

Dr. Freeman Hrabowski, President, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Mr. Sheldon Caplis, Vice President

Mr. Earl Linehan, Major Donor

Findings

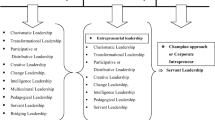

Two particularly salient conclusions stand out from the findings of this study. The data indicate that the university and college presidents in this study use both transactional and transformational leadership approaches in fund raising, and all four presidents exhibit transformational behaviors and characteristics in their fund-raising activities. In addition, they use a transactional approach as a stepping stone to a transformational posture. The answers to question number two support Bornstein's concept that transformative leaders use transactional and transformational leadership approaches in different situations. According to the presidents, vice presidents, and major donors in this study, one leadership approach does not replace another approach. In fact, the results of this study suggest that transactional and transformational leadership approaches work hand in hand to help the leader and donor accomplish higher-order change in fund raising. Bornstein's transformative leadership concept and Bass and Avolio's (2004) augmentation model of transactional and transformational leadership are integrated with the findings of this study to create the Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model (Figure 1).

The Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model shows how transactional leadership is critical for building a sense of dependability and trust prior to the implementation of transformational behaviors and characteristics. The model indicates how a president's transformational leadership behaviors and characteristics identified in this study (i.e., idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration) create successful fund raising when implemented at the appropriate time and in the right situation.

The Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model illustrates how the presidents in this study use a transactional leadership approach to build trust with donors and then implement transformational leadership behaviors and characteristics to heighten motivation and enhance donor performance. The results of this study show that the commonalities and differences of each president's transformational approach were shaped by the situation, the background and makeup of the institution and individual donor, and the president's specific leadership style. The results reveal which leadership behaviors and characteristics presidents should integrate into their leadership approach to help strengthen their fund-raising success. The following discussion about the findings is organized using the four areas of transformational leadership (i.e., inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and idealized influence) along with the behaviors and characteristics identified in this study.

Inspirational Motivation

Vision

All four presidents emphasize the importance of vision in relation to their highly successful fund-raising activities. The results of this study show that each president had a different, unique method for constructing vision, but each president did use history and story to connect a donor's vision to the institution's vision.

Bornstein emphasizes the need to understand the history and culture of an institution and develop a vision based on its past traditions. She expresses the need for a president to be cautious about bringing a preconceived vision to an institution without regard for the past. During the interviews, Kerr and Odahowski provided examples that show how Bornstein developed a vision for Rollins College in this unique way and connected her fund-raising success to this leadership pattern. At the University of Virginia, Casteen notes that because of the financial situation in 1993 the Board of Trustees demanded that he focus on a transformational leadership approach. Casteen suggests that his transformational assignment was centered on the creation of vision and execution of fund raising. Combined with his intellectual capacity, the University of Virginia's unique, rich history is an important factor that drives the vision of UVA's future. Major donor David Gibson agrees that the driving force of UVA's vision is Casteen's deep understanding of Thomas Jefferson's founding vision. In this way, Bornstein and Casteen develop an inspiring vision that looks back as much as it looks forward. At Vanderbilt University, Gee started his tenure as president with the development of a vision. John Ingram, major donor, underlines Gee's ability to create an inspiring vision by saying that he “polished the apple.” Gee helped constituents “see how good Vanderbilt really is.” Hrabowski clearly articulates and embodies a vision for the University of Maryland, Baltimore County that inspires donors and enhances fund-raising activities. Caplis emphasizes how Hrabowski's values provide a powerful context for vision. Caplis suggests that Hrabowski's ability to not only articulate but to also embody the vision is a vital component in his fund-raising success. Along with Casteen and Bornstein, Hrabowski notes the importance of integrating the past in the creation of a vision for the future, especially in the case of an individual donor. He emphasizes how the construction of vision must incorporate the wants, needs, and motivations of a donor to truly inspire the individual and move them toward a higher-level gift. These examples show how the presidents in this study create a vision and articulate it to their constituency, which is one of the most important findings of this study.

Story

In every case, the presidents created a meaningful, inspiring vision using the institution or the donor's story. The use of story emerged as one of the distinguishing factors in a president's ability to be a highly successful fund raiser. This finding supports Peters and Waterman's (1982) idea that “the transforming leader builds on people's need for meaning and a desire for leadership that creates institutional purpose.” In other words, the leader's story inspires individuals to find the nexus of meaning between the institution's mission and their personal interest. It is at this nexus that the donor's response is at its highest potential.

The interviews clearly support this finding about the power of story. According to Odahowski,

Rita connects these wonderful threads, weaves them into a fabric, and then creates a garment for people to wear. Threads, fabric, garment—it seems like a process that moves naturally from something small and relevant into interconnected pieces that are held together by meaning, and then they become not only practical, keeping the individual warm in the winter and cool in the summer, but also colorful, beautiful, and meaningful to the person wearing it.

These words capture the essence of Bornstein's use of story to create meaning for a donor. The results of this study show that Hrabowski embodies the story. This finding agrees with Bolman and Deals’ (1997) concept “that often symbolic leaders embody their vision in a story…a story about ‘us’ and ‘our’ past, present, and future.” Hrabowski's story works because it taps persuasively into the experience, values, and aspirations of donors. It was the Meyerhoff Scholars Program that captured the true meaning of Hrabowski's life and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County's vision and intertwined the power of story, fund raising, and leadership. Gee frames the use of story in the following way: “You know it's the role of the president to tell the institution's story, and by doing so, not make it an institution, but to make it a living, breathing, soulful being.”

Individualized Consideration

All four presidents displayed behaviors and characteristics that support their strong interest in the individual needs of donors. The results of this study show that this characteristic may be the defining component in why these university and college presidents are able to create such a powerful, inspiring fund-raising vision. The presidents’ ability to communicate and listen was paramount for matching their institution's needs to an individual's passion and interest. Story was the bridge for this connection, but communicating, especially listening, surfaced as a major ingredient in fund-raising success.

Listening

The presidents state that an individual's story can only be matched to a donor's need by listening. Kerr observes that Bornstein “listens intently to a donor and from a sparse conversation interprets the very best of [his or her] story.” Bornstein states that it is the role of the university president “to know what a donor is interested in, what they remember, what they hope for, and what their children are doing. To understand an individual donor in this capacity…a president must listen.” Casteen refers to this “continuous feedback and linking” as an “extended conversation.” This extended conversation was how he framed the single largest gift in University of Virginia's last fund-raising campaign. Casteen believes that “this conversation had a dramatic impact on the university. If the donor were alive today, he would say his legacy came out of this conversation…an extended conversation with a lot of listening and shared ideas and concepts.” Gee states that his tenure as president at Vanderbilt University started with what he called a “listening tour.” He underlines the importance of listening for ensuring an institution's history and culture are aligned with strategic goals. If they are not aligned with strategic goals, history and traditions can act as impediments. In this sense, listening becomes the foundation for Bornstein's notion of how critical the match is between the past and the future.

Gee's interview reveals that fund raising is more than a transaction. Gee refers to donors as partners. This relational term underlines his firm belief that donors are more than numbers on a ledger sheet. At this juncture, the vast difference between a university president and fund raising and a CEO and corporate sales was observed: that is, even though fund raising is a transaction, it is a transaction of a different nature. It is a transformational transaction. It is an exchange fused with meaning and purpose. This idea affirms Bass’ (1985) observation that “although Contingent Reward (transactional) and Individualized Consideration (transformational) both involve helping fulfill the needs of followers or donors, Individualized Consideration focuses on personal growth and recognition, and Contingent Reward attends to promising or providing material rewards and resources.” The distinction is that the payoff to the individual is more of an intrinsic reward. It is more about people, the impact on their lives, and making the world a better place.

According to Caplis, Hrabowski “intuitively listens and gets into another person's experience.” Hrabowski not only listens, but he truly cares about other people's stories: “People tell Freeman their stories because they are comfortable with him. I mean he is truly interested in their stories. Most people don’t get to tell their story…so when someone is truly interested in their story it's different. It stands out.” Hrabowski explains his interest in the individual needs of others in the following way: “Personal characteristics are very important to me: having an interest in helping other people, a willingness to listen to others, believing in the need to help each other become his or her best.”

Institutional ego

Two of the four presidents explain why some leaders listen and attend to the individual needs of donors and why others never seem to understand the necessity of this attribute. Casteen thinks that leaders who are more interested in the needs of the institution instead of personal ego seem to blend into the institution and are more interested in truly understanding the needs of the donor and institution. He calls this “institutional ego.” Those leaders who are more driven by a personal agenda are less likely to genuinely listen and understand this important connection. Bornstein concurs with Casteen:

Some leaders don’t listen because of their arrogance, self-importance, or a lack of appreciation of other people….People give from their soul, their heart, or their brain, and you have to know if its going to be something spiritual that moves them, something personal that touches their heart, or something intellectual that stimulates their mind, and only then can you truly connect with them.

Bornstein is alluding to the concept of institutional ego. This is an essential finding because it suggests that presidents need to be conscious, deliberate listeners. It shows that listening, as a leadership behavior, enables a leader to discover the essential ingredients of an effective vision. If these ingredients do not line up with the needs of a donor and the identity of an institution, then a president's fund-raising activities will be weakened.

Intellectual Stimulation

Thinking in new ways

Casteen had the highest score on intellectual stimulation, and his vice president and major donor state that his strongest attribute is the power of his intellectual ideas. While Hrabowski's values are the driving force behind the effectiveness of his vision, Casteen's intellectual capacity shapes and molds the next big idea or vision for the University of Virginia. The questionnaires and interviews confirm Bass and Avolio's (2004) observation that

leaders become transforming and intellectually stimulating to the extent that they can discern, comprehend, conceptualize, and articulate to their followers the opportunities and threats facing their institution, as well as its strengths and weaknesses, and comparative advantages. It is through intellectual stimulation of followers that the status quo is questioned and that new creative methods of accomplishing the institutions mission are explored.

It was apparent that Casteen questions the status quo, and this behavior inspires donors to invest in new ways to strengthen the mission of the University of Virginia. Bornstein provides an example that shows how intellectual stimulation can create opportunities to strengthen the mission of an institution and enhance fund-raising activities. Bornstein led an effort to encourage a continued discussion about liberal arts education that had been started in 1931 by Rollins College President Hamilton Holt. She organized a conference that took an old idea and brought more than 200 people from across the United States to the Rollins campus to think in new ways about liberal arts education.

In the same way, Hrabowski directly connects intellectual stimulation to his fund-raising activities. Hrabowski refers to intellectual stimulation as “the life of the mind”:

I am excited about the life of the mind and about helping young people especially, and then sometimes not so young people, learn how to think critically and solve problems. I find that I enjoy asking questions of individuals and groups, questions that will push people to think about a topic or issue. And the ability to solve problems and to analyze situations can be very helpful when wanting to help an organization or a group of people move to the next level.

Hrabowski describes the type of questions he uses to encourage new ways of thinking about fund raising:

To me, the life of the mind is about examining self and thinking all the time about what's next? What am I doing with my life? Whereas in fundraising, the questions are: What is the purpose in this? How does fundraising help the institution? Why is it critical to find additional resources?

The results of this study reveal that it is important for a president to question the status quo and encourage donors to look at old problems in new ways. Innovation motivates some donors and should be used by presidents to move an institution to higher levels of achievement.

Idealized Influence

Two of the four presidents received nearly perfect scores on idealized influence, which is separated into two categories: behaviors and attributes. The interviews reveal that the most important characteristic of idealized attribute is trust, and the most important characteristics of idealized behavior are risk taking, bringing out the best in people, high expectations, and values. The findings affirm Bass and Avolio's (2004) observation that

leaders who display conviction; emphasize trust; take stands on difficult issues; present their most important values; and emphasize the importance of purpose, commitment, and the ethical consequences of decisions…are admired as role models in generating loyalty, pride, confidence, and alignment around a shared purpose.

Trust

Bornstein and Hrabowski display these behaviors, and in both cases, these attributes play a key role in their fund-raising success. The interviews reveal that both Bornstein and Hrabowski, unlike Gee and Casteen, were in situations that demanded this type of respect. As a Jewish person, the first woman president at Rollins College, and a traditional fund raiser, Bornstein had many barriers to overcome in order to win the respect of her constituency. In the same sense, Hrabowski was surrounded by racial turmoil and tension, and he had to use a leadership approach that emphasizes behaviors associated with idealized influence.

Values

Hrabowski's values in relation to racial issues and the mission of UMBC combined to create a powerful, symbolic partnership that strongly resonates with donors. These issues elevate Hrabowski's values in the eyes of donors and inspire them to financially support these values. The Meyerhoff Scholars program was the nexus where these values and the donors’ financial support were brought together to transform the institution.

Risk taking

Risk taking was the only behavior shared by all four presidents. Based on these findings, it appears that risk taking is an essential attribute of a university president who is a successful fund raiser. Bornstein was recognized as a risk taker, and her colleagues suggest that she works better with individuals who have some capacity for taking risk. Casteen was characterized as a leader who was not operating at his full potential unless he was taking risks. Sweeney went so far as to portray Casteen as a leader who

doesn’t like calm water. If it is going too smoothly, he starts rattling the cage. He is at his best when there is a level of creative tension in the environment where he is pushing us or where he is being pushed forward.

Casteen agrees:

If I have been successful at fundraising, it is my willingness to take the risk of asserting a larger purpose and staking our survival on getting it done. People who are not prepared to take the risk involved in saying we are to do something that nobody has ever done and then leading others to do it and giving them the credit for it when they accomplish it don’t succeed at this job.

Gee was also portrayed as a risk taker by donors and colleagues. Vanderbilt University major donor John Ingram states that Gee demonstrated risk taking at its highest level when he reorganized Vanderbilt's intercollegiate sports and recreational activities for students into a single department. This action did not directly affect fund raising, but it displayed his risk-taking nature as a leader and indirectly influenced fund raising by realigning priorities. Hrabowski's risk-taking nature was discussed in relation to his ability to take the University of Maryland, Baltimore County from being on the brink of being closed by the Maryland legislature and to being one of the best producers of scientists and engineers in the United States. These findings affirm Munitz's (1998) observation that “strong leadership requires a willingness to take risk, an ability to dream about alternatives while weighing their consequences, and the capacity to engage colleagues towards a common goal.”

Implications for practitioners and future research

The Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model represents an accurate picture of the leadership approach used by the four university and college presidents who participated in this study. The model combines Bornstein's transformative leadership concept, Bass and Avolio's Augmentation Model of Transformational and Transactional Leadership, and the findings of this study. It is evident from the present study's findings that transactional and transformational approaches were used by the presidents into varying degrees within specific situations, but transformational leadership behaviors were used to a greater extent to heighten motivation and enhance donor response.

The presidents who participated in this study display 14 specific behaviors and characteristics from MLQ's four transformational leadership categories (i.e., inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and idealized influence). It is recommended that future research should examine nine of the 14 behaviors and characteristics highlighted in the Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model: trust (idealized attributes), risk taking (idealized behavior), values (idealized behavior), vision (inspirational motivation), story (inspirational motivation), communication of the vision/story (inspirational motivation), institutional ego (individual consideration), listening (individual consideration), and thinking in new ways (intellectual stimulation).

Transformational attributes

The present study's findings suggest that further research should examine the four elements of transformational leadership, especially the two categories that emerged as the strongest components contributing to fund-raising success: inspirational motivation and individualized consideration. An examination of inspirational motivation may produce a more focused description of vision, the creation of vision from the story of an institution, and the communication of vision through the spoken word and embodiment of the vision. For example, a study that explores a broader group of presidents from more diverse geographical locations and how they construct vision and whether they use the story of the institution in the process would provide richer insight into what level of influence certain approaches in this category have on fund-raising success. Additional studies that examine each transformational behavior may more accurately illustrate the impact that particular components have on strengthening fund-raising activities.

Vice presidents

The role that vice presidents for advancement play in complimenting, enhancing, or even substituting behaviors that a president may be unable to deliver should also be explored in future research. In each case in this study, it was obvious that the vice president plays a critical role in the success of fund-raising activities and may be able to provide leadership behaviors and characteristics that help offset the weaknesses of a president's fund-raising skills. In addition, it would be valuable to explore alternative ways to strengthen fund-raising collaborations among a president's colleagues.

Unsuccessful presidential fund raisers

Also, a study should be conducted that examines the extent to which these leadership approaches are used by university presidents who are unsuccessful fund raisers. This type of study would enable the current findings to be compared and contrasted and provide an even clearer picture of the behaviors and characteristics that play a critical role in successful fund raising. Additionally, research that considers overall cultural differences from a national and an international perspective may unveil unique differences in how some college and university presidents approach fund raising in the context of varying cultural norms. Beyond cultural differences, a study that found ways to creatively test the Transformative Leadership Fundraising Model in other areas of leadership might also prove beneficial and confirm or deny that the findings are applicable outside the higher education arena.

Training and education

These recommendations for further research should be complemented by training aspiring and current university and college presidents about those behaviors and characteristics that result in successful fund raising. According to Bornstein (2005), a systematic program of continuing education, training, and mentorship's should be developed to assist sitting presidents and potential candidates. Bornstein suggests that it is necessary to define the type and range of knowledge and experience that presidents need to be successful fund raisers. She says that the doctorate in higher education administration provides the broadest base of knowledge directly related to the responsibilities of presidents (30). Another idea is to build on existing programs, a number of which, while outstanding, are often one-shot events. Some of the institutions that sponsor one-shot events could offer more long-term preparatory programs that provide continuing education, training, and mentorships.

Although this study reveals many behaviors and characteristics that contribute to successful fund raising, there are still questions about the leadership approaches used by successful fund raisers. This study is only a starting point for truly understanding which leadership approaches are associated with successful fund raising by a college or a university president. One thing is certain, studies about leadership have not addressed the specific behaviors that create successful fund raising in higher education. Future studies should identify the leadership characteristics that strengthen this important, noble work, and these discoveries should be put into practice. These future practices promise to strengthen university and college presidents’ leadership abilities and enhance their fund-raising activities.

References

Antonakis, J. (2001), “The validity of the transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership model as measured by the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ 5X),” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN.

Avolio, B., Bass, B. and Jung, D. (1999), “Reexamining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 7, pp. 441–462.

Bass, B.M. (1985), Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, Free Press, New York.

Bass, B.M. and Avolio, B.J. (2004), Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, 3rd edn., Mindgarden, Redwood City, CA.

Birnbaum, R. (1989), “Responsibility without authority: The impossible job of the college president,” in J.C. Smart (ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, Vol.V, Agathon Press, New York, pp. 31–56.

Birnbaum, R. (1992), How Academic Leadership Works, Jossey-Bass, New York.

Birnbaum, R. (2002), “The president as storyteller: Restoring the narrative of higher education,” Presidency, 5, 3, pp. 32–39.

Bolman, L.G. and Deal, T.E. (1997), Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Bornstein, R. (2003), Legitimacy in the Academic Presidency: From Entrance to Exit, American Council on Education, ACE/Praeger Series, Westport, CT.

Bornstein, R. (2005), “The nature and nurture of presidents,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, November 4, p. B10.

Burns, J.M. (1978), Leadership, Harper and Row, New York.

Clark, B.R. (1992), The Distinctive College, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ.

Cook, B.C. and Lasher, W.F. (1996), “Toward a theory of fundraising in higher education,” The Review of Higher Education, 20, 1, pp. 33–51.

Cook, W.B. (1994), “A history of educational philanthropy and the academic presidency,” Unpublished manuscript.

Gardner, H. (1995), Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership, HarperCollins, New York.

Gardner, H. (1997), Extraordinary Minds: Portrait of Four Exceptional Individuals and an Examination of Our Own Extraordinariness, Basic Books, New York.

Kuh, G.D. and Whitt, E.J. (1988), “The invisible tapestry: Culture in American colleges and universities,” ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, No. 1, Association for the Study of Higher Education, Washington, DC.

Munitz, B. (1998), “Leaders: Past, present, and future,” Change, 30, 1, pp. 23–26.

Peters, T.J. and Waterman, R.H. Jr. (1982), In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best Run Companies, Harper and Row, New York.

Pettigru, A.M. (1976, May 18), “The creation of organizational cultures,” Paper presented at the joint EIASM-Dansk Management Center Research Seminar, Copenhagen.

Simic, I . (1998). Transformational leadership: The key to successful management of transformational organizational change. The Scientific Journal FACTA Universtatis: Economics and Organization, 1 (6), pp. 149–155.

Sinclair, U. (1923), The Goose Step: A Study of American Education, Author, Pasadena, CA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

1serves as Vice President for University Advancement at Coastal Carolina University. He holds a B.A. in Communications from Charleston Southern University in Charleston, South Carolina and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Higher Education Administration from the University of South Carolina in Columbia, South Carolina.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nicholson, W. Leading Where it Counts: An Investigation of the Leadership Styles and Behaviors that Define College and University Presidents as Successful Fundraisers. Int J Educ Adv 7, 256–270 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijea.2150072

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijea.2150072