Abstract

I further pursue the proposal of Mankiw to consider fairness or “Just Deserts” as the main guide to tax policy. I suggest very different policy conclusions. In particular, I point out some key assumptions that were left implicit in Mankiw's analysis, and question whether these hold in practice. I then suggest a different formal approach to determining a fair policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Last year, this journal printed an address [Mankiw 2010] by N. Gregory Mankiw, “Spreading the Wealth Around: Reflections Inspired by Joe the Plumber.” With the famous exchange between Samuel “Joe” Wurzelbacher and Barack Obama as his launching point, Prof. Mankiw suggested that the utilitarian framework,Footnote 1 which predominates formal analysis of optimal taxation, conflicts with moral intuition. Mankiw argued, and I agree, that most people believe that taxation should be decided by principles of fairness: the pay people keep should be proportional to their contribution to society. He calls this “Just Deserts Theory.” He made a very good point this far, but I must debate some implications he draws. In fact, I believe Mankiw identified a major strength of conservative rhetoric in the public debate on tax policy, and thus gave one answer to “What's the matter with Kansas?”, that is, why the working class vote against their own interests. Conservatives have successfully caricatured the progressive position as placing value on equality of outcomes for its own sake, and this is a value which most Americans find distasteful. In fact, I think life in a world with equality of outcomes is fundamentally unappealing; the struggle to do better, and to be recognized fairly for achievement and productivity, is a basic human drive we would not want to lose. This is why, when conservatives convince the public of Mankiw's basic position that the free market is the ideal, perfectly fair arbiter of Just Deserts, they win broad support for their policies, even when these policies favor the few over the many. Just as serfs once accepted that their position was allotted to them by a divine order, today's growing inequality in wealth is considered acceptable if it is the outcome decreed by the ideal, uncorrupted free market.Footnote 2 Progressives must make it clear that they support the premise of fair compensation for the contributions of each individual, but dispute the notion that fairness is best achieved by an extreme laissez-faire version of capitalism. I will start with some verbal arguments, then, on a slightly more technical level, will point out the limitations in Mankiw's applications of classic economic theorems. Finally, I will suggest a different formal approach to fairness.

In his conclusion, Mankiw implies that Obama's preferred tax policy is inspired by utilitarian considerations while Joe believes in fairness, or Just Deserts. While Mankiw is fair enough to briefly acknowledge that one could make a Just Deserts case for progressive taxation, his main argument is that fairness would favor Joe the Plumber's preferred (less progressive) tax plan over Obama's. Let's look at these claims. First, let's examine a little context surrounding the conservative movement's favorite Obama quote, “spread the wealth around.” Here is the full paragraph from Obama's remarks to Joe:

It's not that I want to punish your success. I just want to make sure that everybody who is behind you, that they’ve got a chance at success, too … My attitude is that if the economy's good for folks from the bottom up, it's gonna be good for everybody. If you’ve got a plumbing business, you’re gonna be better off […] if you’ve got a whole bunch of customers who can afford to hire you, and right now everybody's so pinched that business is bad for everybody and I think when you spread the wealth around, it's good for everybody.

Giving everyone a “chance at success” is a notion of fairness. In fact, it is the classic conservative notion of fairness: equality of opportunity, not equality of outcome. The subsequent sentences are not a statement of values at all, but are a claim in the realm of positive economics: that a tax code that favors the less wealthy will stimulate the economy and be good for everyone. Obama would have a lot of support in this claim, but true or false, it is not a utilitarian justification. A utilitarian would have said something like “If you make a lot of money, the last $10,000 isn’t doing you much good; it would make a much bigger difference to poor people.” As Mankiw says, “it is very possible” that Obama thinks this way, but he certainly didn’t say so to Joe.Footnote 3

In fact, I think Mankiw is quite right that most people on both ends of the spectrum form their beliefs about taxes based on notions of fairness. But what exactly does fairness demand? Here's the view of Warren Buffett, quoted by Obama [Obama 2006]:

I happen to have a talent for allocating capital. But my ability to use that talent is completely dependent on the society I was born into. If I’d been born into a tribe of hunters, this talent of mine would be pretty worthless but I was lucky enough to be born in a time and place where society values my talent, and gave me a good education to develop that talent, and set up the laws and the financial system to let me do what I love doing — and make a lot of money doing it. The least I can do is help pay for all that.

Now, everyone is dependent on a civil society for the dollars they earn, and even for the existence of dollars. Buffett seems to be making the further case that financiers like him are more dependent than most, as a percentage of income. Anyone whose output is easily scalable, including inventors, entertainers, and financiers, is able to create value in proportion to the size of the economy. Fairness would seem to dictate that they owe a greater proportion of their income to the upkeep of society than those in non-scalable professions such as hairdresser, teacher, etc. Buffett does a nice job of explaining this case, and I will later elaborate on this and suggest some ideas of how we might formalize the additional dependence.Footnote 4 Mankiw gives a bit of a nod to the notion that some ultra-rich don’t deserve their full income, but only cites the most obvious cases, “the CEO who pads the board with his cronies and the banker whose firm survives only by virtue of a government bailout.” What about legitimately successful traders like Buffett? He would include himself as deserving higher taxes, but Mankiw seems not to. Mankiw exempts the non-corrupt ultra-rich, citing Spielberg, Jobs, Letterman and Rowling as among those who produce a large value and deserve to keep it. Now, it is true that large-scale entertainers, inventors, and financiers can create a huge value. It may sound fair for them to keep their marginal value, or perhaps have it taxed at the same rate as working-class salaries — to Mankiw, and to conservatives in general, but, as Buffett recommends, we should question this premise. Fairness, of course, ultimately depends on value judgments, but nonetheless we can elucidate these judgments through analysis. Mankiw outlines such an analysis, arguing for the conservative position that everyone deserves their free-market outcome, which will equal their marginal product. Let's take a closer look at his applications of certain classic economic theorems. This is a key passage [Mankiw 2010, p. 295]:

From the perspective of classic liberalism, it is natural to presume that any individual, or group of individuals, should be allowed to leave the large society to live on their own and form smaller communities. They exercise this right if they feel their contributions are insufficiently rewarded — that is, if they can do better on their own. This freedom ensures that the resulting allocation of resources will be in what game theorists call the core … Debreu and Scarf proved that, as the number of players gets large, the core of such games converge to the competitive equilibria … For any other allocation, some group will exercise their right to leave because they are not getting their just deserts.

I have always thought that the section of Atlas Shrugged in which the noble captains of industry go to their own secluded valley to be free of the oppressive liberal state, is a hilarious, unintentional, reductio ad absurdum against the entire position of the book. How exactly are financiers, railroad managers, entertainers, and authors, who profit immensely from living in a large industrial society, going to achieve anywhere close to those profits by moving to a tiny community of elites? Now Mankiw's argument seems to say that it is an actual mathematical theorem that Atlas should shrug, and will profit by doing so, if he receives anything less than his full value under laissez-faire. This is a bit like the classic, infamous proof that all triangles are isosceles; it sounds suspicious, and so we should examine whether the assumptions have been used appropriately. Has an essential aspect of the Core Equivalence Theorem been ignored?

In an exchange economy, a competitive (or Walrasian) equilibrium is an allocation that can occur when each player optimizes his or her behavior, taking some vector of prices as given. The Core Equivalence Theorem says that, in the limit where we make many copies of the original economy, any non-Walrasian allocation will be outside the core.Footnote 5 The key word here is “copies.” The quantity that must become large for the theorem to apply is not the “number of players,” but the number of copies of each kind of player. Intuitively, this is essential in order to force each player to act as a price-taker who cannot use monopoly power to extract rents. Both the formal proof of the result and its intuitive motivation depend crucially on the idea that if someone has too large a share, his or her clones can defect along with the rest of the population. Mankiw has used the theorem in cases where its fundamental logic does not apply: when high earners extract rents thanks to their uniqueness.

There is a similar problem with a result Mankiw cites in the previous paragraph, where he says “… it is also a standard result that in a competitive equilibrium, the factors of production are paid the value of their marginal product.” This result also requires that there be many duplicates of every type of person and product — in Mas-Colell et al. [1995] the result is proved for economies with an infinite multiplicity of each type, and it is noted that the result typically fails when this is not the case. In practice, think of infinite as meaning large enough that no one person or corporation can affect the price of any good. If this actually always holds in real life, it is odd that MBA classes on branding are so popular. To the contrary: not every good is a commodity, and this is one of the major deviations from textbook perfect competition which allows firms to make vastly different profits.

Without even thinking of the technical results, we should question whether it is always possible for everyone to earn their marginal product. Don’t we live in a world with huge complementarities, since at least the days of Adam Smith and the pin factory? Doesn’t that mean that the sum of our marginal products may be far larger than our total product? Furthermore, even when marginal-value allocation is possible, it may not match a reasonable notion of fairness. Consider the stylized example of a single owner of capital and a large set of interchangeable workers with decreasing marginal value. The workers are hired until their marginal value is zero. The marginal value of the owner, who is indispensable, is the full product of the industry. Is this fair? Reflect that if the workers can unionize and be treated as a single player, now the marginal product of the union is equal to that of the owner, and they will negotiate for the surplus on roughly equal terms. (They can no longer both make their marginal products, which will add to double the actual surplus.) An advocate of the notion that market freedom leads to Just Deserts must answer the question “Whose freedom?” This is the title of a book by linguist George Lakoff, who describes how the battle between the conservative and progressive meanings of “freedom” is central to American politics. We must ask whether is it a more fundamental freedom for workers to be free to organize and bargain collectively, or for capitalists to be free to negotiate with individual workers as they see fit. To argue for one of these as unambiguously representing “freedom” without mentioning the other is to try to win what should be a nuanced debate by artful framing. Market outcomes depend not just on productivity, but also on bargaining power. A worker's Just Deserts presumably do not depend on whether he lives in a union-friendly regime, but his outcome depends enormously. Whichever outcome seems fair to you, the other cannot be, so a blanket assertion that “Free market outcomes are fair” falls apart; it is either incomplete or self-contradictory, depending on whether the intended meaning is some particular outcomes, which have been underspecified, or all free-market outcomes.

If marginal value is an unworkable notion of fairness, what might be a better one? A classic idea in cooperative game theory which it is fascinating to apply here is Shapley value. This is related to marginal value. It is computed by the thought experiment of letting individuals enter the economy in a random order. Your marginal value will then depend on who is there when you enter. Your Shapley value is simply your average marginal value across all permutations. Shapley famously showed that this is the unique method of allocating surplus which satisfies some very basic principles of fairness.Footnote 6 Note also that it always gives a unique outcome, while the core frequently either fails to exist or has a huge range of possible outcomes. What sort of results does Shapley value give here? This is a very interesting question, to which I can only offer some preliminary thoughts here. As a first approximation, someone in a highly scalable profession would keep roughly half their income, since they enter the game with, on average, half the population present. (See a more thorough example in the appendix.) There are many possible adjustments to this estimate. For one, it is possible that an inventor or entertainer is not actually much better than a possible replacement, but their product gains value through network effects. That is, if everyone reads a certain book, I get more value from reading it since I can discuss it with many people. In this case, the creator of the product may be able to extract large rents, and their true Shapley value might be much less than half their income. Of course, it is very difficult to distinguish a truly great product from a fad, so I do not suggest that the tax code should try to do so.

Someone in a non-scalable profession, however, creates roughly the same value regardless of the size of society, so they would keep a higher percentage of their income under Shapley value. Whether these considerations reflect fairness is, of course, ultimately a value judgment, but a 50 percent top marginal tax rate is well within the historical range, so such an outcome would not be radical.

A result of Aumann [1975] showed that in a replicator economy (where there are many copies of each agent), the Shapley value will be a Walrasian outcome. Furthermore, as one varies each person's utility function by linear transformations, the Shapley value ranges over all Walrasian outcomes. Thus, in this case the core, Shapley value and set of Walrasian outcomes coincide; if one commits to a particular utility representation, then the Shapley value selects a particular core outcome. Prof. Mankiw, in correspondence, states the view that because no person is truly unique, a replicator economy is a good model of our economy. We are in agreement on the basic philosophical approach of Just Deserts, but the issue of whether replication is a good working assumption crystallizes our differences, and has important consequences for the degree of justice delivered by free markets. Let me explore the replication assumption a little further.

First, from the formal side, we should note that in a replicator economy (satisfying the assumptions of Debreu and Scarf), all core or Walrasian outcomes assign equal surplus to all replicas. The existence of a small set of people who earn far more than others in their profession implies that we do not live in a Debreu-Scarf world; one major assumption which I think has failed is replication. While I essentially agree that truly unique talents or other endowments are exceedingly rare, I think there are many circumstances which make someone effectively unique. Maybe lots of people can write a good fantasy series, but once the first six Harry Potter books had been read by millions, the next book in the series could only be (legally) written by one person, giving J.K. Rowling a powerful monopoly. This sort of effect can easily occur even if differences in talent are small, in large part because of network effects (if I read Harry Potter I can discuss it with just about anyone, not so if I read a competitor of similar quality). This is picking on a rather sympathetic target. We could instead talk about CEOs of large banks and corporations. In the medium run they are not easily replaceable without damaging the company, giving them at least temporarily a form of monopoly power. Few are born unique, but many achieve uniqueness or have it thrust upon them.

The great intellectual advances that illuminated the enormous benefits of the free market, starting with Adam Smith and continuing into the 20th century, have long since been assimilated into our political discourse. The danger is that in some circles the lessons have been learned just a bit too well. The free market then becomes a 21st-century deity whose dictates are perfectly fair and should not be questioned, lest its manna of prosperity cease to rain down upon us. This warning is, of course, unnecessary for economists, who, whatever their political stripe, understand perfectly the limits of core equivalence and welfare theorems. Keeping any nuance is very difficult when intellectual advances are distilled for a larger population, so we must be very careful in how we discuss the practical impact of abstract results.

Notes

The version of utilitarianism Mankiw discussed says that we decide on our policy by maximizing the sum of individual utilities, where utility is concave, meaning that as an individual's wealth increases, each extra dollar adds less to social welfare. If total wealth were constant, social welfare would then be maximized by a completely equal distribution. Utilitarianism does not actually advocate that all wealth be shared equally, however, because it acknowledges the “leaky bucket” principle which says that transfers create inefficiencies by diminishing incentives. However, the leaky bucket is the only rationale that utilitarianism allows for unequal outcomes; there is no notion that the highly productive may deserve their wealth. More general versions of utilitarianism combine individual utilities via a non-linear function, or an arbitrary weighted sum. The best justification for maximizing the simple sum (or average) of utilities is the veil of ignorance; Harsanyi pointed out that if you evaluate welfare as if you are about to be randomly assigned to any position in society and apply expected-utility theory, you would want to maximize society's average utility. Rawls famously used the veil of ignorance to come to a different conclusion, using max-min rather than expected utility. Utilitarianism has been the primary tool for analyzing optimal taxation since the seminal work of Mirrlees.

Exaggerated beliefs in the fairness of economic outcomes, and how such beliefs affect tax policy, have been elegantly modeled by Benabou and Tirole [2006]. In one interpretation of their model, parents try to fool their children into thinking that the world is fair in order to elicit more effort from the children.

I would be unjust not to mention some additional comments I found from Obama, that do refer to decreasing marginal utility of wealth: “… you can derive as much pleasure from a Picasso hanging from a museum as from one that's hanging in your den” (The Audacity of Hope, p. 193). But this wasn’t the argument he made to Joe. My best read of Obama, bearing in mind the difficulty of judging any politician's core beliefs, is that his views are primarily based on fairness, with some additional utilitarian motivation. My larger point is independent of how Obama himself may think: it hardly follows from advocacy of progressive taxation that one's motivation is utilitarian rather than fairness-based.

In other speeches such as [Russell 2006], Buffett has described a view with similarities to utilitarianism. His version of the “veil of ignorance” concept is the “ovarian lottery.” That is, any of us could have been born anywhere in the world, and we should therefore try to build a world where everyone has the opportunity to capitalize on their own talents. His view does seem to differ from the version of utilitarianism common among economists, in that he does not suggest evaluating the world by the distribution of outcomes only, but emphasizes the idea that everyone should have a fair start and equality of opportunity. For instance, lowering the inheritance tax would be like “choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the gold-medal winners in the 2000 Olympics” [BBC News 2001]. In any case, the quote in the main text suggests a Just Deserts point of view more than utilitarianism, but the two are not mutually exclusive.

As Mankiw described, the core consists of precisely those allocations for which no subpopulation can leave the group and do better on their own. For a discussion of the Core Equivalence Theorem, see the original paper [Debreu and Scarf 1963] or, for instance, [Mas-Colell et al. 1995, pp. 652–659].

The first principle is symmetry, which states that identical players get equal allocation; this is unobjectionable. The second concerns a “null player”; it says that a player who contributes zero to any coalition gets zero. This is acceptable if we think of the meaning of “zero allocation” as subject to a normalization. We could agree that we give everyone enough to stay alive and then allocate the rest via Shapley value. The strongest principle is linearity. This says that if we add two value functions (which state how much each coalition can produce) then the amount a person keeps should be the sum of the amounts he would keep if each were the only activity, and similarly for scalar multiplication. This is the least obvious but sounds reasonable.

References

Aumann, Robert 1975. Values of Markets with a Continuum of Traders. Econometrica, 43: 611–646.

Aumann, Robert, and Mordecai Kurz . 1977. Power and Taxes. Econometrica, 45: 1137–1161.

BBC News. 2001. Rich Americans Back Inheritance Tax (February 14).

Benabou, Roland, and Jean Tirole . 2006. Belief in a Just World and Redistributive Politics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121: 699–746.

Debreu, Gerard, and Herbert Scarf . 1963. A Limit Theorem on the Core of an Economy. International Economic Review, 4: 235–246.

Mankiw, N. Gregory 2010. Spreading the Wealth Around: Reflections Inspired by Joe the Plumber. Eastern Economic Journal, 36: 285–298.

Mas-Colell, Andreu, Michael Whinston, and Jerry Green . 1995. Microeconomic Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Obama, Barack 2006. The Audacity of Hope. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Osborne, Martin, and Ariel Rubinstein . 1994. A Course in Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Russell, Georgina 2006. Oracle of Omaha Offers Words of Wisdom. The Wharton Journal (February 27).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful comments from Franco Baseggio, Rein Halbersma, Florian Herold, Josh Sher, and many commentators on the blog “Leisure of the Theory Class” where an earlier version of this article appeared. The biggest thanks go to Greg Mankiw, who, aside from the initial contribution of his thought-provoking article, graciously engaged in a fruitful discussion and suggested that this response be published here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

I’ll give here the Shapley values and core for a simple production economy, with some commentary. This is adapted from Exercise 259.3 and its follow-ups in Osborne and Rubinstein's A Course in Game Theory. Thinking through the economic consequences of this simple formal example sheds some light on the issues from the main text.

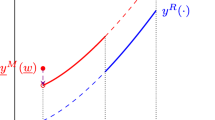

Let there be one owner of capital and a large number of workers whom we can approximate as a continuum of unit mass. The value of a coalition is 0 if it does not have the capitalist, otherwise if there is a mass x of workers present, the value is f (x) for a concave function f, normalized so that f (0)=0, f (1)=1. Since, in a random permutation, the mass of labor present when the capitalist enters has uniform distribution, the Shapley value for the owner is the average of f across this uniform distribution, that is, c = ∫ x=0 1 f(x)dx. By concavity of f, this satisfies 0.5⩽c⩽f (0.5). That is, the owner gets more than half the surplus, but less than the product of half the workers. Labor divides the remaining surplus l=1−c equally, so that 1−f (0.5)⩽l⩽0.5. If f happens to be linear, all of these bounds hold with equality, so surplus is equally divided between capital and labor.

The core can be shown to consist of all allocations where each worker makes at most the marginal product of the last worker, f ′′(1). The key coalitions you have to worry about consist of the owner and all but one worker; it turns out that concavity implies that if you satisfy these coalitions, you are in the core. Therefore, for core allocations the owner gets at least 1−f ′′(1). (Note that it is always in the core for the owner to get everything; here is a simple example where core equivalence is violated, despite a large number of players, if one player is unique.) The core is very harsh towards replaceable workers; if f ′′(1)=0, the unique core outcome is that the workers get nothing, although they are necessary to production. This sort of example illustrates why traditionally the core is seen as a descriptive solution concept — an outcome driven by bargaining power — while the Shapley value is more of a normative concept, driven by fairness. If someone engages in a productive activity but is replaceable, it does seem natural that this would diminish the value he keeps — but by how much? Zero seems unfair; even if the very last worker adds almost no value, I don’t think many would agree that we should then pay them all in peanuts. Like the core, Shapley value changes if labor is treated as a single player — but not as drastically. It turns out to be sort of a compromise between the fully unionized outcome, and the harsh, non-unionized, core outcome.

If Shapley value is more fair than outcomes in an unfettered free market, how might we move closer to it, using a system which will of course be founded on the free market, but mediated by tax and labor policies? There is a literature on “non-cooperative foundations” which deals with questions such as this, but apparently there is no good known non-cooperative path to Shapley value. Even if no mechanism leads precisely to Shapley value, though, it could still provide guideposts as to what general direction policy might move.

The closest work to this discussion of which I am aware is a paper by Aumann and Kurz [1977] which uses the Shapley value to analyze tax policy. A key difference between their work and the present discussion is that they determine the value of a coalition by asking how much value that coalition can expropriate in the political process, not simply how much the coalition can produce. Once the coalition values are determined, the Shapley value is used to determine the ultimate allocation. Nonetheless, as their title suggests, their paper is about outcomes that are achieved through exercise of political power, not outcomes which are necessarily fair. The outcome is very progressive: a negative tax for the poorest, and a marginal tax rate which is always between 50 and 100 percent. Perhaps one moral is that, whatever system we would consider “Just Deserts,” it is possible for the vagaries of politics to create a tax code which deviates from the ideal in either direction.