Abstract

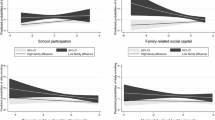

In this paper, we explore one mechanism that may underlie the negative relationship between social capital and smoking: whether social capital strengthens the effect of anti-smoking regulations. We use data on smoking behaviors collected immediately before and after the implementation of smoking bans in public places in Germany in order to determine whether the impact of these bans on smoking prevalence and intensity is greater among individuals richer in social capital. We find that smoking bans reduce both smoking prevalence and intensity mainly among men and that individual social capital strengthens the effect of the bans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The seminal early studies on this topic are Lindström [2003] and Lundborg [2005]. Lindström [2003] shows that daily smoking in Sweden is negatively associated with both social participation and trust, while intermittent smoking is positively associated with social participation and negatively associated with trust. Lundborg [2005] finds a negative correlation between individual social capital (trust and social participation) and drinking and smoking behaviors among Swedish adolescents aged 12–18 years.

See Wagner et al. (2007) for additional information concerning the survey. The 2007 wave does not report data on smoking.

A min-max standardization has been used.

Buonanno and Ranzani (2012), who rely on a similar approach, use the Italian survey on health conditions and health care (Condizioni di Salute e Ricorso ai Servizi Sanitari) produced by ISTAT.

Anger et al. (2011) show that the date of the smoking ban introduction does not relate to a number of state characteristics (state’s GDP per capita, educational attainment, smoking prevalence, the age of the state residents, etc.). According to the authors, the timing of state elections might explain in part the choice of the introduction date of the smoking ban. On page 593, they write, There is some (albeit tentative) evidence that state elections scheduled for early 2008 caused states to adopt a smoking ban earlier.

Of course, the estimate of parameter α3 will be biased instead.

This pattern is also clearly visible in our data. Indeed, the distribution of the variable number of cigarettes smoked per day shows spikes at the multiples of five (see Figure B1 in Appendix).

Christelis and Sanz-de-Galdeano [2011] show that models estimated in such a way have a better fit than linear models that rely on the original data with the heaping of reported values in cigarette consumption.

Other count models, such as the negative binomial model, have been employed. The results are similar to those obtained with the Poisson model.

For an average individual, the marginal effect of the smoking ban on the number of half-packs smoked per day is obtained by multiplying the structural coefficient by the average number of half-packs smoked in the sample. Marginal effects are between two and three times larger than the structural coefficients of the Poisson model reported in Table 6.

Gender specificities in participation in outside activities might also be related to specific gender preferences.

For men the interaction is not significantly different from zero, while the coefficient associated with the ban dummy is negative and significantly different from zero in both cases.

We also estimated models of smoking prevalence and intensity for men using all German states, and thus we included in the sample states that introduced the ban before February 2008. For these states all residents happen to be in the treatment group, implying that they do not contribute per se to identifying the ban effect. Moreover, the common support requirement is violated. The effect of the treatment conditional on residing in one of these states can thus be identified only by means of the functional form assumed in the model. In our case, estimates are slightly smaller, as can be seen in Table B3, but qualitative results for all of Germany roughly confirm those obtained from the baseline specification.

As before, we restrict the sample to the individuals interviewed before the introduction of the actual smoking ban, and the “placebo” bans are state-specific.

Note that results might also differ because the entire sample allows us to measure the effect of the ban on the probability of stopping smoking as well as on smoking initiation, while the sample of former smokers only captures the first effect.

Although the point estimates are larger when model (2) is estimated for the full sample rather than on the sub-sample of former smokers, the marginal effects are smaller for the former, given than the number of half-packs consumed on a daily basis is substantially lower in the full sample (0.97) than in the sample of former smokers (2.78).

The findings are similar when North-Rhine Westphalia is included and when it is excluded from the sample to account for unbalancing.

References

Adda, J., and F. Cornaglia . 2010. The Effect of Bans and Taxes on Passive Smoking. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2 (1): 1–32.

Anger, S., M. Kvasnicka, and T. Siedlera . 2011. One Last Puff? Public Smoking Bans and Smoking Behavior. Journal of Health Economics, 30 (3): 591–601.

Becker, G., and K. Murphy 2000. Social Economics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Buonanno, P., and M. Ranzani . 2012. Thank you for not Smoking: Evidence from the Italian Smoking Ban. Health Policy, 109 (2): 192–199.

Brown, T.T., C.H. Colla, and R.M. Scheffler . 2011. Does Community-Level Social Capital Affect Smoking Behavior? An Instrumental Variables Approach, mimeo.

Christelis, D., and A. Sanz-de-Galdeano . 2011. Smoking Persistence Across Countries: A Panel Data Analysis. Journal of Health Economics, 30 (5): 1077–1093.

D’Hombres, B., L. Rocco, M. Suhrcke, and M. McKee . 2010. Does Social Capital Determine Health? Evidence From Eight Transition Countries. Health Economics, 19 (1): 56–74.

Durlauf, S.N., and M. Fafchamps 2005. Social Capital — Chapter 26, in Handbook of Economic Growth, edited by P., Aghion, and S.N. Durlauf. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Folland, S. 2006. Value of Life and Behavior Toward Health Risks: An Interpretation of Social Capital. Health Economics, 15 (2): 159–171.

Folland, S., K. Islam, and K. Oddvar . 2011. The Social Capital and Health Hypothesis: A Theory and New Empirics Featuring the Norwegian HUNT Data, mimeo.

Glaeser, E.L., B.I. Sacerdote, and J.A. Scheinkman . 2003. The Social Multiplier. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1 (2–3): 345–353.

Göhlmann, S., and C.M. Schmidt . 2008. Smoking in Germany: Stylized Facts, Behavioral Models, and Health Policy. Ruhr Economic Papers #64.

Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales . 2010. Civic Capital As The Missing Link. NBER Working Paper 15845.

Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales . 2008. Alfred Marshall Lecture. Social Capital as Good Culture. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6 (2–3): 295–320.

Jones, A.M., A. Laporte, N. Rice, and E. Zucchelli . 2011. A model of the impact of smoking bans on smoking with evidence from bans in England and Scotland. HEDG WP 5/11.

Kvasnicka, M. 2010. Public Smoking Bans, Youth Access Laws, and Cigarette Sales at Vending Machines. Ruhr Economic Papers #173.

Li, S., and J. Delva . 2011. Does Gender Moderate Associations Between Social Capital and Smoking? An Asian American Study. Health Behavior & Public Health, 1 (1): 41–49.

Li, S., and J. Delva . 2012. Social Capital and Smoking Among Asian American Men: An Exploratory Study. American Journal of Public Health, 102 (S2): S212–S221.

Lindström, M. 2003. Social Capital and the Miniaturization of Community Among Daily and Intermittent Smokers: A Population-Based Study. Preventive Medicine, 36 (2): 177–184.

Lindström, M. 2008. Social Capital and Health-Related Behaviors, in Social Capital and Health, edited by I., Kawachi, S.V., Subramanian, and D., Kim. New York: Springer.

Lindström, M. 2009. Social Capital, Political Trust and Daily Smoking and Smoking Cessation: A Population-Based Study in Southern Sweden. Public Health, 123 (7): 496–501.

Lundborg, P. 2005. Social Capital and Substance use Among Swedish Adolescents — an Explorative Study. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (6): 1151–1158.

Origo, F., and C. Lucifora . 2010. The Effect of Comprehensive Smoking Bans in European Workplaces. IZA DP 5290.

Rocco, L., and E. Fumagalli 2014. The Empirics of Social Capital and Health, in The Economics of Social Capital and Health, edited by S., Folland, and L., Rocco. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co.

Takakura, M. 2011. Does Social Trust at School Affect Students’ Smoking and Drinking Behavior in Japan? Social Science & Medicine, 72: 299–306.

Tampubolon, G., S. V. Subramanian, and I. Kawachi . 2013. Neighbourhood Social Capital and Individual Self-Rated Health in Wales. Health Economics, 22 (1): 14–21.

Wagner, G.G., J.R. Frick, and J. Schupp . 2007. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) — Scope, Evolution and Enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 127 (1): 139–169.

Wang, H., and D.F. Heitjan . 2008. Modelling Heaping in Self-Reported Cigarette Counts. Statistics in Medicine, 27 (19): 3789–3804.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Nicolas Sirven, the participants of IV Workshop of the “Global Network on Social Capital and Health,” and to two referees for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A

In this appendix we show that the parameter α2 of model (2), estimated by means of OLS, correctly identifies the component of the smoking ban effect depending on individual social capital.

Given X and μ s and the level of individual social capital SCis1=k, we compute the following conditional expectations for banis1=1 and banis1=0, respectively:

Being E(ɛ is |banis1=1, SCis1=k,X,μ s )=E(ɛ is |banis1=0, SCis1=k,X,μ s ) due to the conditional randomness of the treatment variable, the effect of the smoking ban when individual level of social capital is k is given by:

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rocco, L., d'Hombres, B. Social Capital and Smoking Behavior. Eastern Econ J 40, 202–225 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2014.4