Abstract

The size distribution of firms in Uganda is highly skewed to the right both in 1997 and 2005. In this article I examine a potential explanation behind the shape of the size distribution in Uganda and identify, using data from 1997, a distortion from the tax environment that seems to bring together observed patterns in firm size. Two changes in tax audit strategy generate an increase in expected costs from taxation and entice entrepreneurs to restrain their hiring of labour in order to pass under tax officials’ radar. First, we observe a steep rise in audit probability at 10 employees, which generates a cluster of firms at 8 employees. Second, tax officials start relying on sales instead of size to set audit targets for firms with more than 25 employees. This change also implies that tax officials extract more taxes and bribes from the larger firms they inspect. The effect of this second change is so important that it generates a measurable discontinuity in the density of firm size around 27 employees. I show that most of the 1997 patterns are still observable almost a decade later.

Abstract

La distribution de la taille des entreprises en Ouganda est fortement biaisée à droite en 1997 et en 2005. Nous explorons une explication potentielle derrière la forme de la distribution de la taille des entreprises en Ouganda et à l’aide de données de l’année 1997, nous identifions une distortion dans l’environnement fiscal qui semble influencer la taille des entreprises. Deux changements dans la stratégie d’audit fiscal génèrent une augmentation des coûts anticipés de la taxation et incitent les entrepreneurs à limiter leur embauche de main d’oeuvre afin de passer inaperçus auprès du fisc. Tout d’abord, nous observons une augmentation abrupte de la probabilité d’un audit à partir de 10 employés, ce qui provoque un regroupement d’entreprises à 8 employés. Ensuite, lorsqu’ils établissent leur cible d’audit pour les entreprises de plus de 25 employés, les agents du fisc commencent à se fier aux chiffres de vente, au lieu de se fier au nombre d’employés. Ce changement implique également que les agents fiscaux sont en mesure de soutirer plus de taxes et de pots-de-vin des grandes entreprises qu’ils inspectent. L’effet de ce deuxième changement est tellement important qu’il génère une discontinuité mesurable dans la densité de la taille des entreprises aux alentours de 27 employés. Nous montrons que les tendances de 1997 sont toujours observables presqu’une décennie plus tard.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data are from the 2006 World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

We show in the Online Appendix that not only medium firms seem to be missing in Uganda and other developing countries, but large firms also. This is in line with Hsieh and Olken (2014).

The UES data set has generated publications in key journals. Svensson (2003) examines the determinants of bribe payments for public services. Gauthier and Reinikka (2006) find that medium firms are shouldering a disproportionate share of the total tax burden in Uganda. Fisman and Svensson (2007) find that corruption has three times the negative effect of taxation on firm growth. This article complements these findings by documenting the effect of the Ugandan fiscal environment on input misallocation.

This is in line with findings by Bigio and Zilberman (2011), who argue that it might be optimal for the IRS, the fiscal authority in the United States, to condition monitoring on inputted income based on labour when imperfectly observing reported profits.

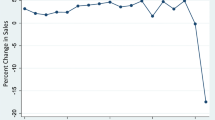

In the Online Appendix, I also show that smaller firms exhibit lower growth rates of sales than their larger counterparts.

Gauthier and Reinikka (2006) argue that ‘smaller firms may find it easier to slip out of the tax collector’s net as enforcement costs easily exceed tax revenues collected’ in Uganda. In a 1998 report from the Article IV Consultation for Uganda by the IMF, it is also noted that the Ordinary Audit Section has a ‘target (…) to carry out 75 audits a month, 50 per cent of which would be on the largest taxpayers’. However, a procedure explaining how the Ugandan tax administration identifies these largest tax payers is nowhere to be found.

For the sake of brevity, I refer the interested reader to McCrary (2008) for a discussion of these advantages.

Most likely, micro enterprises are under-represented in the sample as these firms account for a small fraction of total formal employment in Uganda and are most likely not registered in the census. I discuss how this might affect the results.

Other taxes include the National Social Security Fund levy, the excise tax, the withholding tax import duties, the presumptive tax on small businesses and the local property tax.

The question was: ‘Many business people have told us that firms are often required to make informal payments to public officials to deal with customs, taxes, licences, regulations, services, etc. Can you estimate what a firm in your line of business and of similar size and characteristics typically pays each year?’.

If the true level of sales is higher than reported and the true level of taxes paid is lower than reported, then the results on the effect of tax evasion are a lower bound. See Gauthier and Goyette (2014) for a complete discussion of the limitations of this constructed variable.

These results are robust to the use of the whole sample of firms and different size bins and bandwidths (see Online Appendix).

Multiple testing increases the likelihood of witnessing a rare event and of rejecting the null. A Bonferroni correction implies dividing the chosen statistical significance level, for example, 1 per cent, by the number of independent hypotheses being tested, n=18. This gives a significance level of approximately 0.05 per cent with a critical value of 3.291. From Table 2, I see that the t-statistic at 27 employees remains significant after such correction.

Note that density estimates are equal to zero for negative values of the size variable.

Onji (2009) shows that firms divide their operations into smaller operating units to circumvent the VAT threshold in Japan.

Given the binary nature of the dependent variable, logit or probit regressions might have been better choices to carry out this analysis. However, logit and probit regressions present a major caveat when it comes to testing the equality of coefficients across groups because these tests confound the magnitude of the regression coefficients with residual variation (Allison, 1999). Given that there is yet little agreement on a method to test the equality of coefficients across groups for logit and probit regressions (see Long, 2009 and Williams, 2009), I present in the text the results from a linear probability model and present logit results in the Online Appendix.

Comparing small and medium firms (with an upper bound of 75 employees) does not qualitatively affect the results of the t-test.

I also control for capital but report the coefficients for capital in the Online Appendix.

Number of observations is 141 for bribes and 186 for taxes.

I also note in the left panel that the smallest of the small firms pay more bribes. This is probably due to the fact that these firms are on the verge of illegality and may be harrassed by bureaucrats for permits and licences (Djankov et al, 2002). See Online Appendix for further details.

Results not qualitatively affected if we use taxes or bribes per employee.

Comparing average taxes between small and medium firms does not qualitatively affect the results of the t-test.

The density estimates are based on an Epanechnikov kernel.

In Table 1, I also note an unfavourable and significant sixfold difference in average tax savings per dollar worth of bribing between medium firms and all other firms (t-test: Online Appendix).

Example of countries with a discrete VAT threshold abound. See Table 1 in Keen and Mintz (2004) for a list of selected countries.

References

Alfaro, L., Charlton, A. and Kanczuk, F. (2009) Plant-size distribution and cross-country income differences. In: NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics 2008. Cambridge, MA: University of Chicago Press, pp. 243–272.

Allison, P.D. (1999) Comparing logit and probit coefficients across groups. Sociological Methods & Research 28 (2): 186–208.

Andrews, D.W. (1993) Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 61 (4): 821–856.

Bigio, S. and Zilberman, E. (2011) Optimal self-employment income tax enforcement. Journal of Public Economics 95 (9): 1021–1035.

Cabral, L.M. and Mata, J. (2003) On the evolution of the firm size distribution: Facts and theory. American Economic Review 93 (4): 1075–1090.

Chow, G.C. (1960) Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 28 (3): 591–605.

Clementi, G. and Hopenhayn, H. (2006) A theory of financing constraints and firm dynamics. Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (1): 229–265.

Cleveland, W.S. (1979) Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association 74 (368): 829–836.

Cooley, T. and Quadrini, V. (2001) Financial markets and firm dynamics. American Economic Review 91 (5): 1286–1310.

Dabla-Norris, E., Gradstein, M. and Inchauste, G. (2008) What causes firms to hide output? The determinants of informality. Journal of Development Economics 85 (1–2): 1–27.

de Soto, H. (1989) The Other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World. London: IB Tauris.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F. and Schleifer, A. (2002) The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (1): 1–37.

Fisman, R. and Svensson, J. (2007) Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence. Journal of Development Economics 83 (1): 63–75.

Fortin, B., Marceau, N. and Savard, L. (1997) Taxation, wage controls and the informal sector. Journal of Public Economics 66 (2): 293–312.

Gauthier, B. and Gersovitz, M. (1997) Revenue erosion through exemption and evasion in Cameroon, 1993. Journal of Public economics 64 (3): 407–424.

Gauthier, B. and Reinikka, R. (2006) Shifting tax burdens through exemptions and evasion: An empirical investigation of Uganda. Journal of African Economies 15 (3): 373–398.

Gauthier, B. and Goyette, J. (2014) Taxation and corruption: Theory and firm-level evidence from Uganda. Applied Economics, 2755–2765, doi:10.1080/00036846.2014.909580.

Goyette, J. (2012) Imperfect Enforcement of a Tax Threhsold: The Consequences on Efficiency. GREDI, University of Sherbrooke, Working Paper.

Grimm, M., Gubert, F., Koriko, O., Lay, J. and Nordman, C. (2013) Kinship ties and entrepreneurship in western Africa. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 26 (2): 125–150.

Hansen, B.E. (2000) Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica 68 (3): 575–603.

Hoff, K. and Sen, A. (2006) The kin system as a poverty trap? In: S. Bowles, S.N. Durlauf and K. Hoff (eds.) Poverty Traps. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Hopenhayn, H. (1992) Entry, exit, and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium. Econometrica 60 (5): 1127–1150.

Hsieh, C. and Klenow, P. (2009) Misallocation and manufacturing productivity in China and India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (4): 1403–1448.

Hsieh, C. and Olken, B. (2014) The Missing ‘Missing Middle’. Working paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts, p. 25.

IMF (1998) Uganda: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix. IMF Country Staff Report, Washington DC.

IMF (2009) Uganda: 2008 Article IV Consultation and Fourth Review Under the Policy Support Instrument. IMF Country Report No. 09/79, Washington DC.

Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., McMillan, J. and Woodruff, C. (2000) Why do firms hide? Bribes and unofficial activity after communism. Journal of Public Economics 76 (3): 495–520.

Keen, M. and Lockwood, B. (2010) The value added tax: Its causes and consequences. Journal of Development Economics 92 (2): 138–151.

Keen, M. and Mintz, J. (2004) The optimal threshold for a value-added tax. Journal of Public Economics 88 (3–4): 559–576.

Lee, D.S. and Lemieux, T. (2010) Regression discontinuity designs in economics. Journal of Economic Literature 48 (2): 281–355.

Long, J.S. (2009) Group Comparisons in Logit and Probit Using Predicted Probabilities. Working paper Indiana University, Indiana.

McCrary, J. (2008) Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. Journal of Econometrics 142 (2): 698–714.

Onji, K. (2009) The response of firms to eligibility thresholds: Evidence from the Japanese value-added tax. Journal of Public Economics 93 (5): 766–775.

Platteau, J.-P. (2000) Institutions, Social Norms, and Economic Development. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Quandt, R.E. (1958) The estimation of the parameters of a linear regression system obeying two separate regimes. Journal of the American Statistical Association 53 (284): 873–880.

Reinikka, R. and Svensson, J. (2006) Using micro-surveys to measure and explain corruption. World Development 34 (2): 359–370.

Restuccia, D. and Rogerson, R. (2008) Policy distortions and aggregate productivity with heterogeneous establishments. Review of Economic Dynamics 11 (4): 707–720.

Sleuwaegen, L. and Goedhuys, M. (2002) Growth of firms in developing countries, evidence from Cote d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Economics 68 (1): 117–135.

Stock, J.H. (1994) Unit roots, structural breaks and trends. Handbook of econometrics 4 (Part 10): 2739–2841.

Svensson, J. (2003) Who must pay bribes and how much? Evidence from a cross section of firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (1): 207–230.

Tybout, J. (2000) Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature 38 (1): 11–44.

Williams, R. (2009) Using heterogeneous choice models to compare logit and probit coefficients across groups. Sociological Methods & Research 37 (4): 531–559.

Acknowledgements

I thank participants at various conferences, Giovanni Gallipoli, David Green, Thomas Lemieux and Patrick Richard, as well as two anonymous referees for their constructive comments. All errors remain my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the European Journal of Development Research Website (www.palgrave-journals.com/ejdr).

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goyette, J. The determinants of the size distribution of firms in Uganda. Eur J Dev Res 26, 456–472 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.15

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2014.15