Abstract

Much research has been devoted to the early adoption and the continued and habituated use of information systems (IS). Nevertheless, less is known about quitting the use of IS by individuals, especially in habituated hedonic settings, that is, IS discontinuance. This study focuses on this phenomenon, and argues that in hedonic IS use contexts (1) IS continuance and discontinuance can be considered simultaneously yet independently by current users, and that (2) IS continuance and discontinuance drivers can have differential effects on the respective behavioral intentions. Specifically, social cognitive theory is used to point to key unique drivers of website discontinuance intentions: guilt feelings regarding the use of the website and website-specific discontinuance self-efficacy, which counterbalance the effects of continuance drivers: habit and satisfaction. The distinctiveness of continuance and discontinuance intentions and their respective nomological networks, as well as the proposed research model, were then empirically validated in a study of 510 Facebook users. The findings indicate that satisfaction reduces discontinuance intentions directly and indirectly through habit formation. However, habit can also facilitate the development of ‘addiction’ to the use of the website, which produces guilt feelings and reduces one’s self-efficacy to quit using the website. These factors, in turn, drive discontinuance intentions and possibly the quitting of the use of the website.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agarwal R and Karahanna E (2000) Time flies when you’re having fun: cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Quarterly 24 (4), 665–694.

Ajzen I (2001) Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1), 27–58.

Ajzen I (2002) Residual effects of past on later behavior: habituation and reasoned action perspectives. Personality and Social Psychology Review 6 (2), 107–122.

Anderson JC and Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103 (3), 411–423.

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84 (2), 191–215.

Bandura A (1986) Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Bandura A (1998) Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health 13 (4), 623–649.

Bandura A (2004) Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior 31 (2), 143–164.

Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM and Heatherton TF (1994) Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin 115 (2), 243–267.

Beaudry A and Pinsonneault A (2005) Understanding user responses to information technology: a coping model of user adaptation. MIS Quarterly 29 (3), 493–524.

Beaudry A and Pinsonneault A (2010) The other side of acceptance: studying the direct and indirect effects of emotions on information technology use. MIS Quarterly 34 (4), 689–710.

Bhattacherjee A (2001) Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly 25 (3), 351–370.

Cacioppo JT and Berntson GG (1994) Relationship between attitudes and evaluative space: a critical review, with emphasis on separability of of positive and negative substrates. Psychological Bulletin 115 (3), 401–423.

Cacioppo JT, Gardner WL and Berntson GG (1999) The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: form follows function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (5), 839–855.

Cenfetelli RT and Schwarz A (2011) Identifying and testing the inhibitors of technology usage intentions. Information Systems Research 22 (4), 808–823.

Chandon P, Morwitz VG and Reinartz WJ (2005) Do intentions really predict behavior? Self-generated validity effects in survey research. Journal of Marketing 69 (2), 1–14.

Charlton JP and Danforth IDW (2007) Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Computers in Human Behavior 23 (3), 1531–1548.

Charlton JP and Danforth IDW (2010) Validating the distinction between computer addiction and engagement: online game playing and personality. Behaviour & Information Technology 29 (6), 601–613.

Compeau DR and Higgins CA (1995) Computer self-efficacy: development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly 19 (2), 189–211.

Compeau D, Higgins C and Huff S (1999) Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: a longitudinal study. MIS Quarterly 23 (2), 145–158.

Connelly CE, Zweig D, Webster J and Trougakos JP (2012) Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior 33 (1), 64–88.

Cruz A (2013) Farewell facebook, and good riddance. ABC Univision, ABC News.

DeLone WH and McLean ER (2003) The delone and mclean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems 19 (4), 9–30.

Dimoka A (2010) What does the brain tell us about trust and distrust? Evidence from a functional neuroimaging study. MIS Quarterly 34 (2), 373–396.

Dzewaltowski DA, Noble JM and Shaw JM (1990) Physical-activity participation: social cognitive theory versus the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 12 (4), 388–405.

Eid M and Diener E (2001) Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: inter- and intranational differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (5), 869–885.

Eisenberg N (2000) Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology 51 (1), 665–697.

Feldman JM and Lynch JG (1988) Self-generated validity and other effects of measurment on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 73 (3), 421–435.

Fornell C and Larcker D (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1), 39–50.

Freud S (1961) Civilization and its Discontents. (translated and edited by j. Strachey), W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

Furneaux B and Wade M (2010) The end of the information system life: a model of is discontinuance. Data Base for Advances in Information Systems 41 (2), 45–69.

Furneaux B and Wade M (2011) An exploration of organizational level information system discontinuance intentions. MIS Quarterly 35 (3), 573–598.

Jasperson JS, Carter PE and Zmud RW (2005) A comprehensive conceptualization of post-adoptive behaviors associated with information technology enabled work systems. MIS Quarterly 29 (3), 525–557.

John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ and Hapke U (2004) Self-efficacy to refrain from smoking predicted by major depression and nicotine dependence. Addictive Behaviors 29 (5), 857–866.

Khalifa M and Liu V (2007) Online consumer retention: contingent effects of online shopping habit and online shopping experience. European Journal of Information Systems 16 (6), 780–792.

Klass ET (1978) Psychological effects of immoral actions: the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin 85 (4), 756–771.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD and Binder JF (2013) Internet addiction in students: prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior 29 (3), 959–966.

LaRose R, Lai YJ, Lange R, Love B and Wu YH (2005) Sharing or piracy? An exploration of downloading behavior. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11 (1), 22.

Liang HG and Xue YJ (2009) Avoidance of information technology threats: a theoretical perspective. MIS Quarterly 33 (1), 71–90.

Limayem M and Cheung CMK (2008) Understanding information systems continuance: the case of internet-based learning technologies. Information & Management 45 (4), 227–232.

Limayem M, Hirt SG and Cheung CMK (2007) How habit limits the predictive power of intention: the case of information systems continuance. MIS Quarterly 31 (4), 705–737.

Lindell MK and Whitney DJ (2001) Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (1), 114–121.

MacKenzie SB and Podsakoff PM (2012) Common method bias in marketing: causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing 88 (4), 542–555.

Marlatt GA and Donovan DM (Eds) (2005) Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. The Gilford Press, New York.

Moran S, Wechsler H and Rigotti NA (2004) Social smoking among us college students. Pediatrics 114 (4), 1028–1034.

Mosher DL (1965) Interaction of fear and guilt in inhibiting unacceptable behavior. Journal of Consulting Psychology 29 (2), 161–167.

Oliver RL (1977) Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on postexposure product evaluations: an alternative interpretation. Journal of Applied Psychology 62 (4), 480–486.

Oloffson K (2010) Why is it so hard to delete your facebook account? Time, New York.

Orbell S, Blair C, Sherlock K and Conner M (2001) The theory of planned behavior and ecstasy use: roles for habit and perceived control over taking versus obtaining substances. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 31 (1), 31–47.

Orbell S and Verplanken B (2010) The automatic component of habit in health behavior: habit as cue-contingent automaticity. Health Psychology 29 (4), 374–383.

Orford J (1985) Excessive Appetites: A Psychological View of Addictions. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Ouellette JA and Wood W (1998) Habit and intention in everyday life: the multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin 124 (1), 54–74.

Parthasarathy M and Bhattacherjee A (1998) Understanding post-adoption behavior in the context of online services. Information Systems Research 9 (4), 362–379.

Pavlou PA, Liang HG and Xue YJ (2007) Understanding and mitigating uncertainty in online exchange relationships: a principal-agent perspective. MIS Quarterly 31 (1), 105–136.

Pitkanen T, Lyyra AL and Pulkkinen L (2005) Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction 100 (5), 652–661.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB and Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. In Annual Review of Psychology (Fiske ST, Schacter DL and Taylor SE, Eds), Vol. 63, Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, CA, pp 539–569.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y and Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method bias in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5), 879–903.

Polites GL and Karahanna E (2012) Shackled to the status quo: the inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. MIS Quarterly 36 (1), 21–42.

Pollard C (2003) Exploring continued and discontinued use of it: a case study of optionfinder, a group support system. Group Decision and Negotiation 12 (3), 171–193.

Potter-Efron RT (1989) Shame, Guilt and Alcoholism: Treatment Issues in Clinical Practice. Haworth Press, New York.

Robinson TE and Berridge KC (2001) Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction 96 (1), 103–114.

Robinson TE and Berridge KC (2003) Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology 54 (1), 25–53.

Royce JE (1989) Alcohol Problems and Alcoholism. Free Press, New York.

Rushkoff D (2013) Why I’m quitting facebook. CNN Opinion, CNN.

Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB and Steward WT (2000) Emotional states and physical health. American Psychologist 55 (1), 110–121.

Shaffer HJ and Jones SB (1989) Quitting Cocaine: The Struggle against Impulse. Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

Sharma R, Yetton P and Crawford J (2009) Estimating the effect of common method variance: the method-method pair technique with an illustration from TAM research. MIS Quarterly 33 (3), 473–490.

Sheldon KM, Abad N and Hinsch C (2011) Two-process view of facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100 (4), 766–775.

Smith C (2013) 7 statistics about facebook users that reveal why it’s such a powerful marketing platform. Business Insider.

Tangney JP (1991) Moral affect: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (4), 598–607.

Triandis H (1977) Interpersonal Behaviour. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, CA.

Turel O, Connelly CE and Fisk GM (2013) Service with an e-smile: employee authenticity and customer use of web-based support services. Information & Management 50 (2–3), 98–104.

Turel O and Serenko A (2012) The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. European Journal of Information Systems 21 (5), 512–528.

Turel O, Serenko A and Bontis N (2007) User acceptance of wireless short messaging services: deconstructing perceived value. Information & Management 44 (1), 63–73.

Turel O, Serenko A and Bontis N (2010) User acceptance of hedonic digital artifacts: a theory of consumption values perspective. Information & Management 47 (1), 53–59.

Turel O, Serenko A and Giles P (2011) Integrating technology addiction and use: an empirical investigation of online auction users. MIS Quarterly 35 (4), 1043–1061.

Turel O, Yuan YF and Connelly CE (2008) In justice we trust: predicting user acceptance of e-customer services. Journal of Management Information Systems 24 (4), 123–151.

Turel O and Zhang Y (2011) Should i e-collaborate with this group? A multilevel model of usage intentions. Information & Management 48 (1), 62–68.

van Offenbeek M, Boonstra A and Seo D (2013) Towards integrating acceptance and resistance research: evidence from a telecare case study. European Journal of Information Systems 22 (4), 434–454.

Venkatesh V (2000) Determinants of perceived ease of use: integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems Research 11 (4), 342–365.

Venkatesh V, Brown SA, Maruping LM and Bala H (2008) Predicting different conceptualizations of system use: the competing roles of behavioral intention, facilitating conditions, and behavioral expectation. MIS Quarterly 32 (3), 483–502.

Walker LJ and Pitts RC (1998) Naturalistic conceptions of moral maturity. Developmental Psychology 34 (3), 403–419.

Watson D and Clark LA (1994) The Panas-x: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form. University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, pp 1–24.

Webb TL and Sheeran P (2006) Does changing behavioral intentions engender bahaviour change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin 132 (2), 249–268.

Westbrook RA and Oliver RL (1991) The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research 18 (1), 84–91.

Wilson TD, Lindsey S and Schooler TY (2000) A model of dual attitudes. Psychological Review 107 (1), 101–126.

Woollaston V (2013) Facebook users are committing ‘virtual identity suicide’ in droves and quitting the site over privacy and addiction fears. Daily Mail, London.

Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Miller GE, Schulz R and Carver CS (2003) Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29 (12), 1494–1508.

Wyma KD (2004) Crucible of Reason: Intentional Action, Practical Rationality, and Weakness of Will. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Young K (1998) Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior 1 (3), 237–244.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Common method bias assessment

While the risk of CMV is mitigated by the use of multiple version of the survey, it may still exist given that data were self-reported (Sharma et al, 2009). It was examined by multiple techniques, because all CMV assessment techniques have drawbacks (Podsakoff et al, 2003, 2012; MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012). First, the correlation matrix was examined based on Pavlou et al’s (2007) suggestions. Very high correlations (in excess of 0.9) can be indicative of CMV, but the correlations in this study were substantially lower, and quite a few were very low and non-significant (r=0.00 ns to 0.57, P<0.01). Second, Harman’s single factor test was performed. The data for the multidimensional constructs of the model were subjected to principal component analysis with no rotation. This procedure produced seven components that explained 77% of the variance, and the largest one captured only 28% of the variation. Third, a modified Lindell & Whitney (2001) test was performed. An unrelated marker construct, namely affective state of surprise (three items from the PANAS-X inventory by Watson and Clark (1994) – amazed, surprised, astonished) was captured in the survey. These items were included in a factor analysis procedure with all items pertaining to the model’s constructs. The items loaded highly on the affective state of surprise factor (loadings of 0.79–0.81), and had low loadings on all other factors (below 0.30). Forth, a common latent factor (MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012; Podsakoff et al, 2012) that captures the communal variance of all model indicators was added to the CFA model. The CFA model was then estimated with and without this common latent factor, and the differences in loadings were found to be negligible (0.01–0.12) and below the 0.2 cutoff. Taken together, all of these tests indicate that common method bias is unlikely to be pertinent in the data. However, these techniques are imperfect (MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012; Podsakoff et al, 2012), and even their combined conclusion may be imprecise. Thus, future research can collect data such that there is temporal, proximal, or psychological separation between exogenous and endogenous variables. Future research can also go beyond the elimination of common scale properties that was utilized in this study, that is, the shuffling of the survey pages, and try to use other procedural remedies such as more balanced negative and positive items as well as statistical remedies such as measuring one’s response style or controlling for directly measured source of bias (MacKenzie & Podsakoff, 2012; Podsakoff et al, 2012).

Appendix B

Examining potential self-generated validity effects

Self-generated validity describes the potential reactive effects of measurement on outcomes (Chandon et al, 2005). It is possible that asking respondents to report on certain intentions or perceptions makes these intentions or perceptions more accessible in the memory and consequently influence resultant assessments and actions. This can lead to subsequent beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors which are more consistent with the reported intentions and perceptions (Feldman & Lynch, 1988; Chandon et al, 2005)

In the current study, it is possible that asking individuals to report say their levels of addiction may make the addiction symptoms more accessible in their memory, and as such, prime individuals to report on stronger guilt feelings and/or stronger discontinuance intentions toward the hedonic IS. Therefore, the study was designed in a way that allows the mitigation and examination of such potential self-generated validity effects. Specifically, the measures used in this study were spread over four webpages. The first page ((A) demographics and website use and behaviors) was constant, and the remaining three pages ((C) continuance factors, (D) discontinuance factors, and (O) other factors) were rotated. This process has yielded six versions of the survey. Table B1 reports sample sizes and construct means for each version. The order of the pages in each version is reflected in its name. For example, Version 2 had the following page order: demographics and use, continuance, discontinuance, and other factors.

As can be seen, the differences between construct means across versions seem small, and all appear to be in the same range across versions, and in no particular direction. To empirically test whether these small differences in means manifest from version differences, a Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) model was specified and tested in SPSS 20. In this model, the version was specified as a fixed factor and all the measures were specified as dependent variables. Pilai’s Trace of 0.36 (F(186)=0.98) was not significant (P<0.57), indicating no omnibus version-based differences among the data sets. Thus, the order of the presentation of the scales did not significantly influence the way individuals responded to these questions. Hence, it was concluded that self-generation does not seem to be a problem in this data set.

Appendix C

Assessment of differences between continuance and discontinuance intentions

As another preliminary analysis, this study sought to empirically examine whether continuance and discontinuance intentions should be treated as separate factors and whether predictors can have differential effects on both. To this end, differences between these two concepts were established using the criteria for dual-factor phenomena (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1994; Cacioppo et al, 1999). First, the existence of cases in each quadrant in Table 1 was examined. Using median splits for continuance and discontinuance intentions 124 participants (24%) were in Quadrant 1, 160 (31%) in Quadrant 2, 188 (37%) in Quadrant 3, and 38 (7%) in Quadrant 4. Thus, there are possible cases of ‘apathy’ and ‘ambivalence’ in the sample, which indicate that people can have simultaneous low (high) continuance and discontinuance intentions.

Second, a principal component EFA with Promax rotation with the default of κ=4 was performed on continuance and discontinuance intention items. Promax is an oblique rotation which was chosen since the two constructs are expected to be at least moderately correlated. Two components emerged, with high loadings over 0.95 and low cross-loadings, below 0.45. The correlation between the components was −0.56, which demonstrated moderate to high negative correlations, but no major overlap (the constructs share about 30% of the variance).

Third, a CFA model was specified and estimated using AMOS 20 using Maximum Likelihood estimates. The fit indices were acceptable [χ2(df=8)=18.1, χ2/df=2.26, CFI=0.99, IFI=0.99, RMSEA=0.050 with P-close=0.46, and SRMR=0.012]. All loadings were significant (P<0.001), and the correlation between the two factors was −0.58 (P<0.001). A χ2 test was used to contrast this model with a single factor model allowing all six items to load on a single factor [χ2(df=9)=1422.5, χ2/df=158, CFI=0.65, IFI=0.65, RMSEA=0.56 with P-close=0.00, and SRMR=0.20]. The χ2 difference statistic was significant [χ2(1) =1404.4, P<0.000]. Therefore, estimating the correlation between the two factors statistically significantly reduced the χ2 statistic, and the two-factor model significantly fits the data better than does the single-factor model.

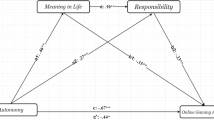

Lastly, a sequence of χ2 difference tests was performed on a model that included both continuance and discontinuance intention and the hypothesized predictors of discontinuance intentions. The coefficients and explained variances are reported in Table C1, and the χ2 comparisons are reported in Table C2. The results show that all the predictors, except for satisfaction, separately and together, had statistically different influences on continuance and discontinuance intentions. Habit had a much stronger effect on continuance (β=0.35) than on discontinuance intentions (β=−0.16), and guilt had the opposite pattern – much stronger effect on discontinuance (β=0.38) than on continuance (β=−0.12) intentions. Similarly, self-efficacy to discontinue had a significant effect on discontinuance intentions (β=0.17), but no significant effect on continuance intention. Satisfaction was the only predictor that equally catered to both continuance and discontinuance decisions. The correlation between continuance and discontinuance intentions was −0.45, P<0.001. These findings imply that discontinuance intentions can have their own predictors (e.g., guilt and self-efficacy to discontinue) and a nomological net different from this of continuance intentions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turel, O. Quitting the use of a habituated hedonic information system: a theoretical model and empirical examination of Facebook users. Eur J Inf Syst 24, 431–446 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.19

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.19