Abstract

Empirical human rights researchers frequently rely on indexes of physical integrity rights created by the Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) or the Political Terror Scale (PTS) data projects. Any systematic bias contained within a component used to create CIRI and PTS carries over to the final index. We investigate potential bias in these indexes by comparing differences between PTS scores constructed from different sources, the United States State Department (SD) and Amnesty International (AI). In order to establish best practices, we offer two solutions for addressing bias. First, we recommend excluding data before 1980. The data prior to 1980 are truncated because the SD only created reports for current and potential foreign aid recipients. Including these data with the more systematically included post-1980 data is a key source of bias. Our second solution employs a two-stage instrumented variable technique to estimate and then correct for SD bias. We demonstrate how following these best practices can affect results and inferences drawn from quantitative work by replicating a study of interstate conflict and repression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Earlier work has dealt with the potential bias included in SD reports. The construction of the CIRI Physical Integrity Rights index takes that bias for granted. The index starts with SD reports, and then coders also use AI’s Annual Report. When there is a difference between the two sources, ‘our coders treat the Amnesty International assessment as authoritative. Most scholars believe that this step, crosschecking the Country Reports assessment against the Amnesty International assessment, is necessary to remove a potential bias in favour of US allies’ (Cingranelli and Richards, 2010: 400). Alternatively, Hill et al (2013) show that while some NGOs face their own strategic interests to inflate allegations of government abuse, AI strictly adheres to their credibility criterion in human rights reporting.

For instance, Nordås and Davenport (2013) finds support that an important demographic variable, youth bulges, leads to worse human rights practice. This new variable had not been considered until recently, but it has found robust support. Other recent additions to the cannon of covariates include variables measuring NGO shaming (Ron et al, 2005; Murdie and Davis, 2012), international legal instruments (with a focus on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention Against Torture (CAT) (see Simmons (2009), Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui (2007), and Hill (2010) for an introduction to the debate on the role of human rights treaties, and Mitchell et al (2013) for domestic legal traditions. See Hill and Jones (2014) for a review of the empirical human rights literature).

While we focus on PTS because it disaggregates the data by AI and SD, the CIRI data may have the same set of problems. Unfortunately, we cannot test this assertion directly because of the differing ways that CIRI and PTS use AI and SD reports to construct their indexes. The CIRI Physical Integrity Rights index starts with SD reports, then uses AI reports (where available) to corroborate the scores. Whenever the reports produce different scores, the scores generated from AI reports are used because of the potential biased nature of the SD reports. This attempt to account for SD bias is good in theory, but it is also why CIRI remains subject to the criticisms developed in this article. While CIRI is ‘fixing’ all the countries for which there are both SD and AI reports, it is ignoring countries for which there are no AI reports. The result is a data set in which there is a split population – those states for which there are both SD and AI reports (resulting in unbiased scores) and those for which there are only SD scores (resulting in potentially biased scores). If there is no relationship between whether AI reports on a country and important covariates, this will simply increase the ‘noise’ associated with estimation. On the other hand, if where AI does its reporting is associated with covariates, then researchers may be including biased scores into their analyses. AI is less likely to report on countries that the SD includes for non-random reasons. For instance, AI is less likely to include smaller states and states with high GDP/capita. Both economic and demographic variables are important in theories of human rights behaviour, and scholars will be keen to include such variables in their analyses. Since those variables are correlated with whether AI covers them or not, CIRI will suffer from the same bias we have identified in the PTS data, if only to a lesser degree.

PTS is not just the human rights conditions writ large; it specifically relates to a subset of rights called personal/physical integrity rights. Moreover, the measure is limited to the government’s behaviour with respect to those rights. For instance, a country is not held responsible for human rights abuses committed by rebel groups who are operating in the nominal territory of the state. On the other hand, acts of police, even though they may not be condoned at the highest levels of the government, are seen as acts of state despite the fact that those abuses may result from an inability of the state to control its own agents.

While it is possible for the PTSSD and PTSAI to differ by four points, in practice, the largest difference is three points.

Poe et al (2001) subtract the PTSSD from the PTSAI, while we do the opposite. If readers are comparing our results to theirs, they will need to flip signs, but the substantive findings will remain unaltered.

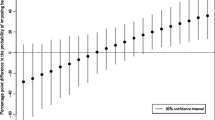

The fact that zero is the most common category is consistent with Poe et al (2001): 54.3 per cent in the full sample and 54.7 per cent in Poe’s sample. However, the weighted centre of the distribution is closer to zero in the full sample

compared to Poe, Carey and Vazquez’s sample (−0.21), which indicates that the distribution has become more normal over time.

compared to Poe, Carey and Vazquez’s sample (−0.21), which indicates that the distribution has become more normal over time.The quotations are taken from the descriptions of the different values of the ordinal scale as discussed on the PTS website: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/ptsdata.php, accessed 5 September 2014.

We obtained the report from Amnesty directly from their website: https://www.amnesty.org/en/search/?documentType=Annual+Report&sort=date&p=6, accessed September 15, 2014. The State Department report is archived by the Hathi Trust and is available at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015014143476;view=1up;seq=379, accessed 15 September 2014.

Note that the black square markers do not indicate the difference of the average μSD−μAI, but the average of the difference μSD−AI. In Figure 2 from (Poe et al, 2001: 662), the authors report μSD−μAI over time even though this is not the concept they discuss throughout the rest of the article. Thus, our analysis is not an exact replication/update of their work.

Corrected values can be treated as continuous or censored to create an ordinal scale, reflecting the ordinal scale used with PTS.

It is worth noting that we do not contend that variables such as trade have no impact on observed human rights performance. Instead, we argue that states holding strategic interest to the US are more likely to have favourable SD reports. That variables like trade may improve actual human rights performance and that it results in more biased SD reports are not mutually exclusive. Any improvement in actual human rights performance should be reflected in both the AI and SD reports. Where these reports diverge, however, we can use the difference between them to predict bias. Moreover, it is not surprising that SD reports reflect US strategic goals. The US is known to consider its strategic interests when creating reports and forecasts. Sahin (2014), for instance, finds that International Monetary Fund (IMF) country forecasts include high degrees of politically motivated bias, reflecting US commitments rather than economic fundamentals. The same US strategic interests have been found to influence decision regarding lending decisions (Barro and Lee, 2005; Stone, 2002, 2004) and foreign aid allocations (Alesina and Dollar, 2000; Bearce and Tirone, 2010; Fleck and Kilby, 2010).

We treat states as ‘allies’ if they are coded as sharing a neutrality, non-aggression, or defensive pact by the Correlates of War alliance data set (Gibler, 2009).

We code regions in the following manner: states with Correlates of War country codes between 1–199 are coded as Americas. Country codes 200–399 are coded as Western Europe, except for former Communist states that succeeded the USSR or Yugoslavia, or that had been part of the Warsaw Pact, who are coded as Eastern Europe. Country codes 400–599 are coded as Africa, 600–799 are coded as Middle East, 800–899 are coded as Asia, and 900–999 are coded as Oceania.

The time period covered in the CIRI data set starts after 1980 to reflect this problem. Our analysis supports the CIRI project’s decision to limit the temporal scope of their data set.

Breen (1996: 4) defines the particular type of truncation that concerns this case as a ‘sample selected:’ ‘y is observed only if some criterion defined in terms of another random variable, z is met, such as if z=1’.

For many quantitative studies, it is common to purposefully restrict the sample to states with a population of at least 100,000.

Following Wright, we include a series of lagged binary variables of the categories of the dependent variable to account for temporal auto-correlation.

We calculate predicted pre-1980 PTSIV scores using the values from Model 2 of Table 1.

We use cut points of 0.5 to recode these instrumented PTS scores into the ordinal scale used by Wright (2014), that is, scores <1.5 are coded as 1, [1.5, 2.5] are coded as 2, [2.5, 3.5] are coded as 3, [3.5, 4.5] are coded as 4, and scores ≥4.5 are coded as 5. We run additional analyses on the unscaled instrumented PTS scores using OLS. Substantive results are the same.’

Constitutive terms each have meaningful zero values, enabling their direct interpretation. Testing for the statistical significance of the interaction term requires calculating the covariance of the interaction and constitutive terms, however, making direct interpretation more difficult. Graphical outputs of the marginal effects support the results discussed above.

The reported results are similar even if we do not bootstrap the standard errors.

References

Alesina, A. and Dollar, D. (2000) ‘Who gives foreign aid to whom and why?’ Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1): 33–63.

Amnesty International. (1980) Amnesty International Report 1980, London: Amnesty International Publications.

Barro, R.J. and Lee, J.-W. (2005) ‘IMF programs: Who is chosen and what are the effects?’ Journal of Monetary Economics 52 (7): 1245–1269.

Bearce, D.H. and Tirone, D.C. (2010) ‘Foreign aid effectiveness and the strategic goals of donor governments’, Journal of Politics 72 (3): 837–851.

Blanton, S.L. (2000) ‘Promoting human rights and democracy in the developing world: US rhetoric versus US arms exports’, American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 123–131.

Blanton, S.L. and Blanton, R.G. (2007) ‘What attracts foreign investors? An examination of human rights and foreign direct investment’, Journal of Politics 69 (1): 143–155.

Breen, R. (1996) Regression Models: Censored, Sample Selected, Or Truncated Data, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Carter, D.B. and Signorino, C.S. (2010) ‘Back to the future: Modeling time dependence in binary data’, Political Analysis 18 (3): 271–292.

Cingranelli, D.L. and Richards, D.L. (2010) ‘The Cingranelli and Richards (CIRI) human rights data project’, Human Rights Quarterly 32 (2): 401–424.

Conrad, C.R., Haglund, J. and Moore, W.H. (2014) ‘Torture allegations as events data: Introducing the ill-treatment and torture (ITT) specific allegation data’, Journal of Peace Research 51 (3): 429–438.

Correlates of War Project. (2011) ‘State system membership list, v2011’, available at http://correlatesofwar.org, accessed 1 September 2014.

Department of State. (1981) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Esaray, J. and Danneman, N. (2014) ‘A quantitative method for substantive robustness assessment’, Political Science Research and Methods 3 (1): 95–111.

Fariss, C.J. (2014) ‘Respect for human rights has improved over time: Modeling the changing standard of accountability’, American Political Science Review 108 (2): 297–318.

Fleck, R.K. and Kilby, C. (2010) ‘Changing aid regimes? U.S. foreign aid from the cold war to the war on terror’, Journal of Development Economics 91 (2): 185–197.

Gibler, D.M. (2009) International Military Alliances, 1648–2008, Washington DC: CQ Press.

Gibler, D.M. and Miller, S.V. (2012) ‘Comparing the foreign aid policies of Presidents Bush and Obama’, Social Science Quarterly 93 (5): 1202–1217.

Gibney, M. and Dalton, M. (1996) ‘The political terror scale’, Policy Studies and Developing Nations 4 (1): 73–84.

Hafner-Burton, E.M. and Tsutsui, K. (2007) ‘Justice lost! The failure of international human rights law to matter where needed most’, Journal of Peace Research 44 (4): 407–425.

Hill, D.W. (2010) ‘Estimating the effects of human rights treaties on state behavior’, Journal of Politics 72 (4): 1161–1174.

Hill, D.W. and Jones, Z.M. (2014) ‘An empirical evaluation of explanations for state repression’, American Political Science Review 108 (3): 661–687.

Hill, D.W., Moore, W.H. and Mukherjee, B. (2013) ‘Information politics versus organizational incentives: When are amnesty international’s ‘naming and shaming’ reports biased?’ International Studies Quarterly 57 (2): 219–232.

Johnson, J.C. (2015) ‘The cost of security: Foreign policy concessions and military alliances’, Journal of Peace Research 52 (5): 665–679.

Kalyvas, S.N. and Balcells, L. (2010) ‘International system and technologies of rebellion: How the end of the cold war shaped internal conflict’, American Political Science Review 104 (3): 415–429.

Lake, D.A. (2007) ‘Escape from the state of nature’, International Security 32 (1): 47–79.

Lake, D.A. (2009) Hierarchy in International Relations, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lebovic, J.H. and Voeten, E. (2009) ‘The cost of shame: International organizations and foreign aid in the punishing of human rights violators’, Journal of Peace Research 46 (1): 79–97.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1995) Data Analysis: An Introduction, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Machain, C.M. and Morgan, T.C. (2013) ‘The effect of US troop deployment on host states foreign policy’, Armed Forces & Society 39 (1): 102–123.

Marshall, M.G. and Jaggers, K. (2013) ‘Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2013, Version p4v2013e [Computer File]’.

Meernik, J., Krueger, E.L. and Poe, S.C. (1998) ‘Testing models of U.S. foreign policy: Foreign aid during and after the cold war’, Journal of Politics 60 (1): 63–85.

Mitchell, S.M., Ring, J.J. and Spellman, M.K. (2013) ‘Domestic legal traditions and states’ human rights practices’, Journal of Peace Research 50 (2): 189–202.

Morrow, J. (1991) ‘Alliances and asymmetry: An alternative to the capability aggregation model of alliances’, American Journal of Political Science 35 (4): 904–933.

Murdie, A. and Davis, D.R. (2012) ‘Shaming and blaming: Using events data to assess the impact of human rights INGOs’, International Studies Quarterly 56 (1): 1–16.

Murdie, A. and Peksen, D. (2013) ‘The impact of human rights INGO activities on economic sanctions’, Review of International Organizations 8 (1): 33–53.

Nau, H.R. (2013) Conservative Internationalism: Armed Diplomacy Under Jefferson, Polk, Truman, and Reagan, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Neufville, J.I. (1986) ‘Human rights reporting as a policy tool: An examination of the state department country reports’, Human Rights Quarterly 8 (4): 681–699.

Neumann, R. and Graeff, P. (2013) ‘Method bias in comparative research: Problems of construct validity as exemplified by the measurement of ethnic diversity’, Journal of Mathematical Sociology 37 (2): 85–112.

Nordås, R. and Davenport, C. (2013) ‘Fight the youth: Youth bulges and state repression’, American Journal of Political Science 57 (4): 926–940.

Poe, S.C., Carey, S.C. and Vazquez, T.C. (2001) ‘How are these pictures different? A quantitative comparison of the US state department and amnesty international human rights reports, 1976–1995’, Human Rights Quarterly 23 (3): 650–677.

Poe, S.C. and Meernik, J. (1995) ‘U.S. military aid in the eighties: A global analysis’, Journal of Peace Research 32 (4): 399–412.

Qian, N. and Yanagizawa, D. (2009) ‘The strategic determinants of U.S. human rights reporting: Evidence from the cold war’, Journal of the European Economic Association 7 (2–3): 446–457.

Richards, D.L., Gelleny, R.D. and Sacko, D.H. (2001) ‘Money with a mean streak? Foreign economic penetration and government respect for human rights in developing countries’, International Studies Quarterly 45 (2): 219–239.

Ron, J., Ramos, H. and Rodgers, K. (2005) ‘Transnational information politics: NGO Human rights reporting, 1986–2000’, International Studies Quarterly 49 (3): 557–588.

Roth, K. (2010) ‘Empty promises? Obama’s hesitant embrace of human rights’, Foreign Affairs 89 (2): c10–c16.

Sahin, A. (2014) International organizations as information providers: How investors and governments utilize optimistic IMF forecasts. Doctoral Dissertation. Washington University in St Louis. Retrieved from Ann Arbor, MI: Proquest/UMI.

Schnakenberg, K.E. and Fariss, C.J. (2014) ‘Dynamic patterns of human rights practices’, Political Science Research and Methods 2 (1): 1–31.

Simmons, B.A. (2009) Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sovey, A.J. and Green, D.P. (2011) ‘Instrumental variables estimation in political science: A readers’ guide’, American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 188–200.

Stock, J.H. and Watson, M.W. (2007) Introduction to Econometrics: International Edition, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Stone, R.W. (2002) Lending Credibility: The International Monetary Fund and the Post-Communist Transition, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stone, R.W. (2004) ‘The political economy of IMF lending in Africa’, American Political Science Review 98 (4): 577–591.

US Department of State. (1981) Country reports on human rights practices, available at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015014143476;view=1up;seq=379, accessed 15 September 2014.

US Department of State. (2012) ‘Foreign Affairs Manual.’ Personnel: Assignments and Details.

Westad, O.A. (1992) ‘Rethinking revolutions: The cold war in the third world’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 29 (4): 455–464.

Westad, O.A. (2005) The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, R.M. and Gibney, M. (2010) ‘The political terror scale (PTS): A re-introduction and a comparison to CIRI’, Human Rights Quarterly 32 (2): 367–400.

Wright, T.M. (2014) ‘Territorial revision and state repression’, Journal of Peace Research 51 (3): 375–387.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

nieman, m., ring, j. the construction of human rights: accounting for systematic bias in common human rights measures. Eur Polit Sci 14, 473–495 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.60

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.60

compared to Poe, Carey and Vazquez’s sample (−0.21), which indicates that the distribution has become more normal over time.

compared to Poe, Carey and Vazquez’s sample (−0.21), which indicates that the distribution has become more normal over time.