Abstract

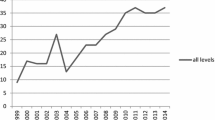

In recent years there has been a growing effort to trace the developments of political science in different countries through the analysis of articles published in academic journals. Building on existing literature on the history of the discipline, this contribution provides an attempt to produce a quantitatively informed description of political science publishing in Portugal from 2000 to 2012. Results show that the yearly output in national journals increased notably, mainly driven by international relations and comparative politics. A strong majority of articles are authored by researchers from domestic institutions. Nevertheless, the period under analysis witnessed an expanding scope beyond the domestic case and an increasing comparative focus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This subsection owes much to Cruz and Lucena’s (1985) contribution, which has been so far the most comprehensive, albeit outdated, historical outline of political science in Portugal.

The course of Political Science (and Constitutional Law) ceased to be lectured in 1911, as a result of the anti-positivist backlash within the Coimbra Faculty of Law.

ISCSPU was a higher education institution whose core mission was to train the top level of the colonial bureaucracy.

Here we broadly follow the concept of institutionalisation used by Cairns (1975) and Jerez-Mir (2010), inspired by Edward Shills, which include a set of structures and standards for knowledge transmission (university departments and positions, undergraduate and graduate degrees), knowledge creation (research institutes, scientific societies, research funding mechanisms) and knowledge dissemination (publishers, journals etc.).

From the 1950s onwards, ISCSPU hosted an undergraduate programme of Social Sciences and Overseas Policy, a research centre (the Board of Overseas Research – Centre for Political and Social Studies), and a journal (Studies in Political and Social Sciences).

This poor picture of political science is nonetheless brighter than Philippe Schmitter’s: ‘The nice thing about Portugal also was that it was an easy place to do research. There were very few Portuguese social scientists. I met them all, and I could have done it in an afternoon. In the early 1970s, Portugal was a country without sociology, let alone political science. I had talked to the few Portuguese living in exile, in Geneva or Paris, who had some knowledge, albeit not very direct, about the country. But, precisely because nobody was doing any social science research, I faced few obstacles gaining access to information’ (in Munck and Snyder, 2007: 318).

The first governing bodies of the APCP still reflected the historical hegemony of law professors in Portuguese political science, as they occupied more than 50 per cent of the positions. Over the years, their importance started to decrease. As of today, the bodies of the APCP only have two law graduates (and none teaches at a law school).

Ferreira-Pereira and Freire (2009) have given a more extensive account of consolidation and internationalisation of IR in Portugal. Most of their paper may be used for understanding the development of political science, since the histories of both disciplines have tended to overlap in most institutional arenas (e.g., at the universities and in the Portuguese Political Science Association).

Although there are no accessible numbers concerning the number of doctoral and post-doctoral public scholarships granted in the last decade within the area of political science, the available statistical data provided by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) shows that in the period between 1994 and 2010, the number of research grant holders in the field of social sciences and humanities was multiplied by five, in the case of doctorates, and by 25, in the case of post-doctorates. However, following the budget cuts affecting public spending in Portugal in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, there has been a steep decrease in the number of scholarships granted from 2010 to 2013. Source: http://www.fct.pt/estatisticas/bolsas/, accessed 19 April 2014.

See the article by Ferreira-Pereira and Freire published in 2009 on Portuguese international relations.

The typology includes the following categories: Courts, judiciary, constitution; Democracy/development; Elections and voting behaviour; Executives and bureaucracy; Federal/local government; Interest groups and social movements; International relations; Legislatures; Methodology; Normative theory; Party systems and organisations; Political economy; Political elites; Public opinion and attitudes; Public policy. Given the permeability of disciplines’ boundaries, it would perhaps be more accurate to state that we have surveyed the universe of publications from ‘political studies’ rather than ‘political science’ stricto sensu. Indeed, given that most of the journals are not devoted exclusively to the field of political science, it can be argued that authors of a relevant share of the surveyed articles would not even identify themselves as political scientists.

The lower figures for institutional research as compared with the studies on public and political behaviour may be a further indicator that lawyers lost ground to sociologists in the shaping of Portuguese political science (at least in the social science journals under analysis).

Articles with a spatial scope are distinct from those with a strictly theoretical or methodological focus.

However, it should be stressed that different outcomes may result from authoritarian experiences as well (Easton et al, 1995).

References

Altman, D. (2012) ‘Where is Knowledge generated? On the productivity and impact of political science departments in Latin America’, European Political Science 11 (1): 71–87.

Anckar, D. (1991) ‘Political Science in the Nordic Countries’, in D. Easton, J.G. Gunnell and L. Graziano (eds.) The Development of Political Science. A Comparative Survey, London: Routledge, pp. 187–200.

Archambault, É., Vignola-Gagne, É., Grégoire, C., Larivière, V. and Gingras, Y. (2006) ‘Benchmarking scientific output in the social sciences and humanities: The limits of existing databases’, Scientometrics 68 (3): 329–342.

Barrinha, A. and Pedro, G.M. (2012) ‘Nota introdutória. As RI portuguesas: para lá de uma ciência social’, Relações Internacionais (R:I) 36: 5–10.

Berndtson, E. (1991) ‘The Development of Political Science: Methodological Problems of Comparative Research’, in D. Easton, J.G. Gunnell and L. Graziano (eds.) The Development of Political Science. A Comparative Survey, London: Routledge, pp. 34–58.

Billordo, L. (2005) ‘Publishing in French political science journals: An inventory of methods and subfields’, French Politics 3 (2): 178–186.

Boncourt, T. (2007) ‘The evolution of political science in France and Britain: A comparative study of two political science journals’, European Political Science 6 (3): 276–294.

Cairns, A.C. (1975) ‘Political science in Canada and the Americanization issue’, Canadian Journal of Political Science 8 (2): 191–234.

Capano, G. and Verzichelli, L. (2010) ‘Good but not enough: Recent developments of political science in Italy’, European Political Science 9 (1): 102–116.

Cruz, M.B. da and Lucena, M. de (1985) ‘Introdução e desenvolvimento da ciência política nas universidades portuguesas’, Revista de Ciência Política 2: 5–41, [reprinted in Cruz, M.B. da (1995) Instituições Políticas e Processos Sociais, Venda Nova: Bertrand Editora, pp. 19–88].

Daalder, H. (1991) ‘Political science in the Netherlands’, European Journal of Political Research 20 (3–4): 279–300.

Easton, D., Gunnell, J.G. and Stein, M.B. (1995) ‘Introduction: Democracy as a regime type and the Development of Political Science’, in D. Easton, J.G. Gunnell and M.B. Stein (eds.) Regime and Discipline: Democracy and the Development of Political Science, Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press, pp. 1–25.

Fernández, M.A. (2005) ‘Ciencia Política en Chile: un espejo intelectual’, Revista de Ciencia Política 25 (1): 56–75.

Ferreira-Pereira, L.C. and Freire, R. (2009) ‘International relations in Portugal: The state of the field and beyond’, Global Society 23 (1): 79–96.

Hayward, J. (1999) ‘British Approaches to Politics: the Dawn of a Self-Deprecating Discipline’, in J. Hayward, B. Barry and A. Brown (eds.) The British Study of Politics in the Twentieth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–35.

Hicks, D. (1999) ‘The difficulty of achieving full coverage of international social science literature and the bibliometric consequences’, Scientometrics 44 (2): 193–215.

Jerez-Mir, M. (2010) ‘The Institutionalization of Political Science: The case of Spain’, in G. Castro and J.M. De Miguel (eds.) Spain in America: The First Decade of the Prince of Asturias Chair in Spanish Studies at Georgetown University, Madrid: Fundación Endesa, pp. 281–329.

Moreira, A. (2007) ‘Political Science in Portugal’, in H.-D. Klingemann (ed.) The State of Political Science in Western Europe, Leverkusen: Barbara Budrich, pp. 311–324.

Munck, G.L. and Snyder, R. (2007) Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Norris, P. (1997) ‘Towards a more cosmopolitan political science?’, European Journal of Political Research 31 (1): 17–34.

Pehl, M. (2012) ‘The study of politics in Germany: A bibliometric analysis of subfields and methods’, European Political Science 11 (1): 54–70.

Stock, M.J. (1991) ‘Political science in Portugal’, European Journal of Political Research 20 (3–4): 425–430.

Wagner, P., Wittrock, B. and Whitley, R. (eds.) (1991) Discourses on Society, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the referee for her/his insightful comments and useful suggestions. Early versions of the article were improved following discussions in Madrid (22nd IPSA World Congress 2012, panel organised by RC33 – The Study of Political Science as a Discipline) and in Lisbon (6th Congress of the Portuguese Association of Political Science 2012, and FCSH/NOVA Graduate Conference 2012). We are grateful to the participants at those venues, and we owe a debt of gratitude to Thibaud Boncourt. Any errors remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

cancela, j., coelho, t. & ruivo, j. Mapping Political Research in Portugal: Scientific Articles in National Academic Journals (2000–2012). Eur Polit Sci 13, 327–339 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2014.18

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2014.18