Abstract

Measuring characteristics of democracy is not an easy task, but anyone who does empirical research on democracy needs good measures. In this article, we present the Democracy Barometer, a new measure that overcomes the conceptual and methodological shortcomings of previous indices. It allows for a description and comparison of the quality of thirty established democracies in the timespan between 1995 and 2005. The article examines its descriptive purposes and demonstrates the potential of this new instrument for future comparative analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The Democracy Barometer is a project within the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) ‘Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century’, sponsored by the Swiss National Foundation. The team working on the Democracy Barometer consists of researchers from the University of Bern (Marc Bühlmann), the Centre for Democracy Studies in Aarau (Lisa Müller) as well as researchers from the Social Science Research Centre Berlin (Wolfgang Merkel, Bernhard Weßels, and Heiko Giebler). For further information, see www.democracybarometer.org.

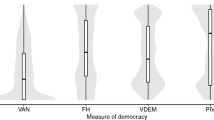

To empirically examine democracy, we need adequate measures. However, measuring democracy is not an easy task. Scholars have criticised several aspects of existing and widely used indices, such as Freedom House, Polity, or the Vanhanen Index of Democratisation (Arndt and Oman, 2006; Bollen and Paxton, 2000; Hadenius and Teorell, 2005).Footnote 2 Munck and Verkuilen (2002) identified three challenges researchers face when attempting to measure democracy: conceptualisation, measurement, and aggregation.

In a nutshell, all three challenges are very poorly met by existing measures of democracy. Regarding concept specification, existing measures are based on a conception of democracy that is too simple. In addition, they lack a sound conceptual logic and suffer from problems of redundancy and conflation. Furthermore, the measurements used to create previous indices do not demonstrate high validity or reliability and some cannot be replicated. Finally, researchers who have used existing measures neither discuss nor justify their aggregation level or their aggregation rules.

In addition to, and precisely because of, their conceptual and methodological shortcomings, previous indices of democracy do not live up to the demands of current democracy research: The question is no longer whether a political system can be considered a democracy or not. Instead, researchers focus more and more on assessing the quality of established democracies (Altman and Pérez-Liñán, 2002; Diamond and Morlino, 2004). However, the well-established indices of democracy, such as the Vanhanen, Polity, or Freedom House indices, are not sensitive enough to measure the subtle differences among established democracies.Footnote 3 Again, the main reason for this is their minimalist conceptual basis. Democracy is a complex phenomenon, and a minimalist measurement cannot do it justice.

‘… existing measures are based on a conception of democracy that is too simple’.

To overcome the shortcomings of previous measures, researchers need a new instrument that copes with the most important conceptual and methodological drawbacks, and is able to measure differences in the quality of established democracies. In this contribution, we present the Democracy Barometer (DB), an instrument that meets these needs.Footnote 4 The conceptual basis and the measurement logic of this instrument are discussed in Sections ‘The Conceptual base of the Democracy Barometer’ and ‘Measuring the Quality of Democracy’. Section ‘The Potential of the Democracy Barometer’ includes first, illustrative results and demonstrates the potential of this new instrument for future analyses by those performing empirical research on democracy.

THE CONCEPTUAL BASE OF THE DEMOCRACY BAROMETER

The DB is based on a middle-range concept of democracy, embracing liberal as well as participatory ideas of democracy (Bühlmann et al, 2008, 2011a).

The liberal concept of democracy originates from classical republicanism in its protective version (Locke; Montesquieu), the classical liberal model of democracy (Mill; Tocqueville), and its more modern developments in the form of the elitist (Michels, 1966 [1911]) or the pluralist models of democracy (Dahl, 1956; Fraenkel, 1962). One of the most explicit versions is Schumpeter's (1950) realist one. The participatory type is rooted in classical Athenian democracy, the developmental form of classical republicanism (Rousseau), ideas about direct as well as participatory democracy (Barber, 1984; Pateman, 1970), and deliberative democracy (Fishkin, 1991; Habermas, 2001). Embracing both models of democracy, the DB overcomes the minimalism of previous measures of democracy, but does not include maximalist understandings of democracy. In other words, we abstain from perspectives that focus on the output of democratic systems such as equal distribution of resources (Meyer, 2005).

Contrary to most existing democracy measures, the concept of the DB consists of a stringent discussion and stepwise theoretical deduction of fundamental elements of democracy. Using three core principles of liberal and participatory democracy, we deduced nine functions. We speak of functions because they are seen as functional elements for the quality of democracy. The degrees of fulfilment of these nine functions are defined by two components each that are themselves measured by different theoretically deduced subcomponents and indicators.

THE PRINCIPLES: FREEDOM, EQUALITY, AND CONTROL

The starting point is the premise that a democratic system tries to establish a good balance between the normative, interdependent values of freedom and equality, and that this requires control. Control is also valuable in a democracy because it is the institutionalised checking of the political authorities that distinguishes democratic systems from autocracies.

Freedom can be defined as the absence of heteronomy (Berlin, 2006). Protecting and guaranteeing individual rights under a secure rule of law is one of the minimal conditions for democratic regimes (Beetham, 2004). Democracy and the rule of law are even seen as equiprimordial or ‘gleichursprünglich’ (Habermas, 2001). Only in a government operating under the secure rule of law where the state is bound to follow the effective law and acts according to clearly defined prerogatives (Elster, 1988) can individuals be sure that they are protected from the state infringing on their personal freedom. Constitutional individual liberties include the legal protection of life, freedom of opinion, and property rights, included in Locke's (1974) definition of property.Footnote 5

Additional basic rights that ensure democracy are the freedom of association and of opinion that enable a lively and active public sphere (Linz and Stepan, 1996). Freedom of opinion, however, depends on the circumstances of information (Sartori, 1987). A free flow of information must be installed, and the possibility to take part in the public sphere must be ensured. Hence, individual liberties, rule of law, as well as an active and legally secured public sphere guarantee the principle of freedom (Beetham, 2004). Historically as well as functionally, freedom is strongly associated with the idea that citizens have sovereignty. Indeed, freedom seems possible only where all citizens have equally guaranteed political rights (Habermas, 1992). This leads us to the second principle: equality.

Equality, particularly political equality, means that all citizens are treated as equals in the political process (Dahl, 1956, 1998), and that all citizens must have equal access to political power (Saward, 1998). Thus, the rather abstract principle of equality leads to a more concrete feature of democratic governance: full inclusion of all persons subject to the legislation of a democratic state (Dahl, 1998: 75). There are at least two reasons to regard equality as a fundamental principle of democracy. First, in modern, secular societies, there is no objective basis on which to evaluate whether A's conduct of life is better than B's. Second, ‘no persons are so definitely better qualified than others to govern that they should be entrusted with complete and final authority over the government of the state’ (Dahl, 1998: 75). Political equality thus aims at the equal formulation, equal consideration, and equal inclusion of all citizens’ preferences. Inclusive participation, representation, and transparency are required to reach this goal.

An equal formulation of preferences depends on participation. As Lijphart (1997: 3) states, unequal turnout heavily constrains the quality of a democratic system because the ‘privileged voters are favoured over underprivileged non-voters’. Thus, electoral as well as alternative participation should be as equal as possible; a systematic abstention of specific social groups from the political process is seen as a disqualification of democratic equality (Teorell et al, 2007). Furthermore, equality requires the inclusion of the preferences of all persons that can possibly be affected by political decisions taken within a democratic regime (Dahl, 1998). In representative democracies, inclusion presupposes high descriptive and substantial representation. An important prerequisite for equal preference formation and adequate responsive decision making is transparency (Stiglitz, 1999). When freedom of information is restricted and the public visibility of the political process is not given, the information mismatch may lead to unequal participation and, consequently, the unequal inclusion of preferences.

‘Guaranteeing as well as optimising and balancing freedom and equality are the core challenges of a democratic system’.

Freedom and equality interact and can constrain one another, but they are not generally irreconcilable (Talmon, 1960; Tocqueville, [1835] 1997). Guaranteeing as well as optimising and balancing freedom and equality are the core challenges of a democratic system. In order to keep freedom and equality in a dynamic balance, a further fundamental principle of democratic rule is needed: control. Of course, control is not a simple auxiliary that balances the two other principles but an important basis of democracy itself: Control is understood to mean that citizens hold their representatives accountable and responsive. Representative democracy thus heavily depends on control of power that is exercised vertically as well as horizontally.

Horizontal control functions as a network of institutions that mutually constrain one another (O’Donnell, 1994). This network of relatively autonomous institutions surveys, checks, and balances, i.e., mutually constrains, the elected authorities. Through mutual constraints, control of the government is not restricted to periodic elections but complemented by a mutual check and balance of constitutional powers. In representative democracies, vertical control is exercised by means of free, fair, and competitive elections (Manin et al, 1999). It is the elections that allow the citizens to make decisions that balance freedom and equality (Meyer, 2009). Effective elections must be competitive because only competition allows a real choice and induces the political elite to act responsively (Bartolini, 1999, 2000). However, to ensure responsiveness, the result of the elections must be effective. Vertical control is of no avail if the elected representatives lack the capability to govern, i.e., to implement the electoral mandate. Thus, governments need a certain control over the political process, i.e., the capacity to effectively implement collective democratic decisions. Only democratically legitimised political decisions or the rule of law may constrain the governmental autonomy (Etzioni, 1968).

FROM PRINCIPLES TO FUNCTIONS

The three principles must be guaranteed and functionally secured by different elements, which we call functions. These functions are deduced from the three principles (see Figure 1). According to the discussion above, freedom depends on the guarantee of individual liberties (including freedom of association and of opinion, i.e., a lively public sphere) under a secure rule of law. Equality is only possible if there is transparency, equal participation and responsiveness in terms of representation. Finally, in well-functioning democracies, control must be exercised vertically as well as horizontally. Furthermore, the government must have the capability to act in a responsive way.

In a nutshell, we argue that the quality of a given democracy is high when these nine functions are fulfilled to a high degree. However, a simultaneous maximisation of all nine functions is not possible, not only because of the tensions between freedom and equality, but also because democracies are systems whose development is perpetually negotiated by political as well as societal forces. Hence, democracies weigh and optimise the nine functions very differently. We thus suggest that a variety of different qualities of democracy exists.

We further argue that the degree of fulfilment of each of these nine functions can be measured. This requires a further conceptual step: the different functions are based on constitutive components. Hence, each function is further disaggregated into two components, which finally leads to several subcomponents and indicators. In order to account for the shortcomings of previous democracy measures, we made sure to capture within each component both legal rules as well as the effective constitutional reality. The following section provides a very short description of the composition of the nine functions. Unfortunately, there is not enough space for a thorough description of all the indicators and measures we used. Thus, the discussion of the functions and components must remain somewhat vague. Details regarding the definition, coding, sources and type of data of all indicators can, however, be found in our codebook (Bühlmann et al, 2011b, also see www.democracybarometer.org).

Individual Liberties

The existence and guarantee of individual liberties is the most important prerequisite for democratic self- and co-determination. Individual liberties primarily secure the inviolability of the private sphere. This requires the right to physical integrity (component 1). This component embraces constitutional human rights provisions and the ratification of important human rights conventions. This serves as an indication that the right to physical integrity is incorporated into a country's culture (Keith, 2002; O’Donnell, 2004). The effective and real protection of this right requires that there are no transgressions by the state, such as torture or other cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatments or punishments (Cingranelli and Richards, 1999). Furthermore, ‘[S]tates are only effective in rights protection to the extent that citizens themselves are prepared to acknowledge the rights of others’ (Beetham, 2004: 72). We thus use the homicide rate and violent political actions as proxies to measure the effectiveness of the right to physical integrity.

The second component comprises another aspect of individual liberties, the right to free conduct of life. On the one hand, this encompasses freedom of religion and freedom of movement. On the other hand, it requires that property rights are adequately protected. Again, these measures distinguish between constitutional provisions guaranteeing the free conduct of life and the effective implementation and impact of these rights.

Rule of law

Individual liberties and political rights (see below) require protection in accordance with the rule of law (Habermas, 1992). Rule of law designates the independence, the primacy, and the absolute warrant of and by the law. This requires the same prevalence of rights as well as formal and procedural justice for all individuals (Beetham, 2004; Rawls, 1971). Equality before the law (component 1) is based on constitutional provisions for the impartiality of courts. In addition, the legal framework must be independent and effectively impartial, i.e., it must not be subject to manipulation (O’Donnell, 2004). The quality of the legal system (component 2) depends on the constitutionally provided professionalism of judges (Keith, 2002; La Porta et al, 2004) and on the legitimacy of the justice system. The justice system cannot receive legitimacy by means of elections (like the other two powers). Rather, judicial legitimacy is based on the citizens’ confidence in the justice system (Bühlmann and Kunz, 2011; Gibson, 2006) and in the institutions exercising the monopoly of legitimate force.

Public Sphere

The principle freedom is completed by the public sphere function. Here, individual rights have an essential collective purpose. Taking part with others in expressing opinions and seeking to persuade and mobilise support are considered important aspects of freedom (Beetham, 2004: 62). The discourse about politics and moral norms takes place in the public sphere (Habermas, 1992), and a vital civil society and a vivid public sphere are ensured by the freedom of association (component 1) and the freedom of opinion (component 2). Freedom of association must be constitutionally guaranteed. In addition, according to social capital research, a vital civil society relies on the density of associations with political and public interests (Putnam, 1993; Teorell, 2003; Young, 1999). Formal social capital is seen as a sign of a well-functioning free articulation and collection of preferences. Freedom of opinion presupposes constitutional guarantees as well. In modern, representative democracies, public communication primarily takes place via mass media. Thus, media should provide a wide forum for public discourse and enable opinion formation by the broad diffusion of information (Graber, 2003).

Competition

Vertical control of the government is established via free, regular, and competitive elections. Bartolini (1999, 2000) distinguishes four components of democratic competition, two of which – vulnerability (component 1) and contestability (component 2) – best concur with our middle-range concept of democracy and our idea of vertical control (Bartolini, 2000). Vulnerability corresponds with the uncertainty of the electoral outcome (Bartolini, 2000; Elkins, 1974), which is indicated by the closeness of election results as well as the degree of concentration of parliamentary seats. Furthermore, formal rules have an impact on vulnerability: the district size and the legal possibility of redistricting can influence competition. Contestability refers to the stipulations that electoral competitors have to meet in order to be allowed to enter the political race. The effective chance of entering is measured by the effective number of electoral parties, the ratio of parties running for seats to the parties winning seats, and by the existence and the success of small parties (Bartolini, 1999; Tavits, 2006).

Mutual constraints

The horizontal and institutional dimension of control of the government is encompassed by mutual constraints of constitutional powers. The balance of powers first depends on the relationship between the executive and the legislature (component 1). An effective opposition as well as constitutional provisions for mutual checks in terms of possibilities for supersession or dissolution guarantee the mutual control of the first two branches (Ferreres-Comella, 2000). Of course, there must be additional checks of powers (component 2). On the one hand, mutual constraints are completed by the third branch in the form of constitutional jurisdiction, i.e., the guaranteed possibility to review the constitutionality of laws. On the other hand, federalism is seen as an important means of control. In line with research on federalism, the degrees of decentralisation as well as effective sub-national fiscal autonomy are incorporated into the measure (Schneider, 2003).

Governmental capability

One important feature of representative democracy is the chain of responsiveness (Powell, 2004). Citizens’ preferences are collected, mobilised, articulated, and aggregated by means of elections and translated into parliamentary or legislative seats. The chain has a further link, namely responsive implementation. Policy decisions must be in line with the initial preferences. A responsive implementation, however, requires governmental capability, i.e., the availability of resources (component 1) and conditions for efficient implementation (component 2).Footnote 6 Public support is one important resource for governments (Chanley et al, 2000; Rudolph and Evans, 2005) since they sometimes need to implement unpopular policies in order to secure the citizens’ preferences in the long run. Furthermore, long terms of legislature and governmental stability facilitate a more continuous and thus more responsive implementation (Harmel and Robertson, 1986). Efficient implementation is more difficult when it encounters opposition from groups of citizens who use strikes, demonstrations, or even illegitimate anti-governmental action to stop it. Similarly, governmental capability is impaired if non-political actors, such as the military or religious powers, are able to influence implementation. Conversely, an efficient bureaucracy can help to facilitate the implementation.

Transparency

A lack of transparency or secrecy has severe adverse effects on the quality of democracy and negatively affects equality. ‘Secrecy provides the fertile ground on which special interests work; secrecy serves to entrench incumbents, discourage public participation in democratic processes, and undermine the ability of the press to provide an effective check against the abuses of government’ (Stiglitz, 1999: 14). Thus, transparency means no secrecy (component 1). Secrecy can become manifest in the form of corruption and bribery (Stiglitz, 1999), which are thus taken as a proxy for low transparency. The unjustified favouritism of particular interests is also linked to rules of party financing. The second component measures whether a democracy offers provisions for a transparent political process. In this sense, an effective freedom of information legislation, which guarantees that official records concerning the political process are easily accessible, is crucial (Islam, 2006). In addition, transparency depends on the degree to which media are allowed to cover political affairs. Hence, media must not face political control or censorship, and a country's media regulation should not restrict the media and their content too strongly. Finally, the perceived willingness of office-holders to openly communicate and justify their decisions, reflects a country's general culture of transparency.

Participation

In a high-quality democracy, citizens must have equal participation rights: all persons who are affected by a political decision should have the right to participate in shaping that decision. This implies that all citizens in a state must have suffrage rights (Banducci et al, 2004; Paxton et al, 2003). Furthermore, these rights should be used in an equal manner (Teorell, 2006), i.e., there must be no participation gaps concerning resources or social characteristics. The equal respect and consideration of all interests by political representatives is only possible if participation is as widespread and as equal as possible (Lijphart, 1997; Rueschemeyer, 2004). Disproportional turnout in terms of social characteristics or different resources ‘may mirror social divisions, which in turn can reduce the effectiveness of responsive democracy’ (Teorell et al, 2007: 392). Therefore, the equality of participation (component 1) must be considered. Of course, the effective use of participation (component 2) is also important. Based on the idea that high turnout goes hand in hand with equal turnout (Lijphart, 1997), the DB considers the level of electoral, as well as non-institutionalised, participation. In addition, the effective use of participation can be facilitated by different rules (for example voting in advance, or registration).

Representation

In a democracy, all citizens must have the possibility of co-determination. In modern democracies, this is usually ensured by means of representative bodies. Responsive democracies require that all citizens’ preferences are adequately represented in the political decision making process. On the one hand, this means substantive representation (component 1). High distortion in terms of high disproportionality between votes and seats, or in terms of low issue congruence among the representatives and the represented, are signs of an unequal inclusion of preferences (Holden, 2006; Urbinati and Warren, 2008). One possibility to measure low substantive representation is the comparison of the left–right assessments of the citizens with the left–right positions of the parties in parliament. Of course, structural opportunities, such as a high number of parliamentary seats or direct democratic institutions, can help to better include preferences into the political system (Powell, 2004). On the other hand, equal consideration of citizens’ preferences is ensured by descriptive representation (component 2), especially for minorities. The access to political office for ethnic minorities must not be hindered by legal constraints (Banducci et al, 2004). The DB also focuses on women as structural minorities. Adequate representation is an important claim for approaches to descriptive representation (Mansbridge, 1999; Wolbrecht and Campbell, 2007). After more than 100 years of women's suffrage rights, this claim should be fulfilled in any established democracy.

MEASURING THE QUALITY OF DEMOCRACY

As discussed in the introduction, a democracy measure must not only adequately specify its theoretical concept, but it must also face the challenges of measurement and aggregation. The DB is based on the idea that we can measure the degree of fulfilment of the nine functions discussed above. For this purpose, the components are further divided into subcomponents that are then measured by several indicators each. There is not enough space to discuss each indicator in this article (see Bühlmann et al, 2011b, www.democracybarometer.org), but it is worth noting that the DB consists of a total of 100 indicators, which were selected from a large collection of secondary data. In order to overcome the shortcomings of previous democracy measures, the final indicators had to meet several criteria. First, we attempted to avoid indicators that are based on expert assessments. As Bollen and Paxton (2000) have shown, such subjective evaluations are often debatable and not particularly transparent. We strictly avoided giving our own assessments and rely as often as possible on either ‘objective’ official statistics, or constructed indicators on the basis of representative surveys (such as the World Values Surveys, the Eurobarometer, or the World Competitiveness Yearbook, to give only three examples). Second, to reduce measurement errors, we made an effort to include indicators from a variety of sources for every subcomponent (Kaufmann and Kraay, 2008). Third, the DB tries to avoid ‘institutional fallacies’ (Abromeit, 2004). The DB is based not only on indicators that measure the existence of constitutional provisions, but also on indicators assessing their real manifestation. Each component consists of at least one subcomponent measuring rules in law (i.e., constitution) and one subcomponent measuring rules in use (i.e., constitutional reality).

‘… the DB consists of a total of 100 indicators … selected from a large collection of secondary data’.

With regard to the aggregation of the indicators, it is necessary to discuss scaling thresholds. For the DB, these thresholds are set on the basis of ‘best practice’. This procedure reflects the idea that democracy should be seen as a political system that continuously redefines and alters itself, depending on ongoing political as well as societal deliberation (Beetham, 2004). Consequently, each given democracy weights the principles and functions differently. To specify ‘best practice’, we defined a ‘blueprint’ country sample. This includes thirty established liberal democracies, i.e., all countries that have constantly been rated as full-fledged democracies by both the Freedom House and the Polity index from 1995 to 2005.Footnote 7 Within this blueprint sample, all indicators were standardised to a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 indicates the highest value (i.e., best practice with regard to the fulfilment of the function) and 0 the worst value within the 330 country-years (thirty countries in 11 years).

‘… reflects the idea that democracy should be seen as a political system which continuously redefines and alters itself …’

The conceptualisation of the DB with its different levels of abstraction further requires the definition of aggregation rules. The first two levels of aggregation – from indicators to subcomponents and from subcomponents to components – are based on arithmetic means. In the following steps (components to functions, functions to principles, principles to ‘Quality of Democracy’), the idea of the optimal balance is implemented: the value of the higher level is calculated using a formula that rewards high values at the lower level but penalises incongruence between pairs of values.Footnote 8

THE POTENTIAL OF THE DEMOCRACY BAROMETER

The main aim of the DB is to describe different profiles of democracy. We assume that some of the nine functions can be seen as trade-offs, rivalling each other to some extent. In addition, we expect that different democratic regimes weight the nine functions differently, and thus attempt to achieve different optima. These different optima or shapes of democracy can best be illustrated by cobweb diagrams where the axes represent the democratic functions.

Figure 2 is an example of such cobweb diagrams for Finland, Italy, and the United States for the years 1995, 2000, and 2005.

In these three countries, there is no variation with regard to their ratings by common democracy measures. But as Figure 2 clearly shows, both the size and the shapes of the cobwebs differ considerably across countries as well as across time in the DB. The shapes illustrate quite well the idea that functions can be weighted differently.

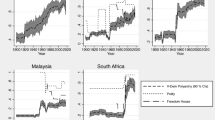

Even though a simultaneous maximisation of all nine functions is not possible, their combination can be optimised to increase the overall quality of democracy. We thus suppose that the countries also differ in terms of their quality of democracy, i.e., our aggregated democracy score. Figure 3 depicts the development of our three illustrative cases: Finland, Italy, and the United States.

Overall, the mean quality of democracy in our sample of established democracies slightly increased from 63.1 to 66.6 between 1995 and 2000 and then slightly decreased to 65.5 by 2005. All in all, this picture neither supports the pessimistic crisis of democracy hypothesis nor the optimistic end of history hypothesis. Looking at the 11-year period of 1995–2005, we observe blueprint countries in which the overall quality of democracy seems to have decreased from the mid-1990s to 2005. This is the case for Italy (with a decrease of −9.3 between 1995 and 2005) and the United States (−2.2) but also for seven other countries (the Czech Republic, Portugal, Costa Rica, Ireland, Australia, France, and Germany). In the remaining twenty-one countries, including Finland (+1.8), the quality of democracy increased over time. Although in some countries the improvement is rather small (less than 5 points in Denmark, Hungary, Norway, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Sweden, Spain, Austria, Slovenia, Belgium, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Africa), other countries enhanced their quality of democracy quite remarkably (more than 5 points between 1995 and 2005 in Canada, Iceland, Poland, the United Kingdom, Malta, Japan, and Switzerland).

As for our three exemplary countries, the figure depicts the intuitively expected differences. Finland has a higher quality of democracy than the United States and Italy. In addition, especially in Italy and the United States, changes in the quality of democracy can be traced back to important government changes. Considering that no indicator within the DB captures the party or ideological composition of governments, this can be taken as a sign of the validity of this new index.

Of course, the DB has the potential to analyse these developments in a much more fine-grained way. Indeed, it is not foremost the overall aggregate index but the different functions that should serve for cross-country and longitudinal comparisons. We can observe, for instance, that the decrease of the Italian quality of democracy is mainly due to a decline in the functions ‘representation’ and ‘rule of law’. Similarly, the reduction of the quality of democracy in the United States can be traced back to a decline in the functions ‘rule of law’ and ‘individual liberties’. As for Finland, its increasing quality is caused by improved governmental capability as well as transparency.

Further detailed insights can be gained by performing a longitudinal analysis of the principles. A nice example is found in the United Kingdom, where we can observe a remarkable shift in the relative emphasis of freedom and equality following the historical government change in 1997. Although during the Major government, freedom seemed to be more important than equality, this was slowly reversed under the Blair government.

However, the DB does not only allow for descriptive analyses. In the remainder of this article, we provide a brief overview of the huge potential of this new instrument for future comparative democracy research.

First, the aggregate measure of the overall quality of democracy can be used as a dependent as well as an independent variable. This may help to provide further evidence for important discussions within democracy research, such as modernisation theory (Robinson, 2006); the debate on the crisis of democracy (Keane, 2009); the examination of challenges to democracy, such as mediatisation or globalisation (Kriesi et al, 2007); institutional engineering (Cain et al, 2003); or the discussion of the relationship between democracy and political performance (Roller, 2005). First tentative results show that economic globalisation seems to foster the quality of democracy and that economic crises have a diminishing effect (Bühlmann, 2009). Furthermore, consensual systems appear to have a higher quality of democracy than majoritarian systems (Merkel and Giebler, 2009). However, this conclusion does not apply to all of the nine functions (Bühlmann et al, 2011d). In addition, there seem to be interesting positive relationships between the quality of democracy and human development, the welfare state and measures of social equality (Bühlmann et al, 2011a). Finally, a high quality of democracy apparently also fosters individual generalised trust and political support (Freitag and Bühlmann, 2009).

Second, the DB not only allows for analyses using the overall quality of democracy index, but also the different function values. First analyses of the impact of the media on the quality of democracy, for instance, show that well-balanced and critical media do not mobilise citizens’ participation (Müller and Wüest, 2010).

Third, to adequately measure the underlying concepts of the DB, new and interesting indicators were developed. For example, a new measure of issue congruence or a new measure of the ideological balance of the press system can help to enhance research in the respective fields.

Fourth, the scope of these analyses can soon be expanded as the sample of the DB will be enlarged by additional countries, especially from Latin America and Eastern Europe. Moreover, the period of analysis is extended from 1990 to 2007. Given this new sample, analyses of different developments concerning the quality of democracy in different regions and of young democracies will become possible (Bühlmann, 2011). Thus, the DB will soon allow for more specific discussions in the field of democratisation research. Depending on future funding, the data of the DB will be updated every year.

Fifth, if data are provided, the DB can be applied to other objects of analysis. For example, the conceptual basis can be used to analyse the quality of democracy of supranational (EU), subnational, or local polities. The analysis of subnational entities is, of course, most interesting in federalist states (for Switzerland see Bühlmann et al, 2009).

‘The greatest potential of the DB … lies in its open structure’.

The greatest potential of the DB, however, lies in its open structure. Detailed documentation of the concept and the indicators, as well as all the data, is published online (www.democracybarometer.org). Researchers are invited to use and improve the data and the concept of the DB. We are aware that our conceptualisation of democracy is only one of countless different models. The availability of all indicators should allow researchers to build and to measure other concepts of democracy. Other combinations, other procedures of scaling and weighting or the addition of other, newer, and better indicators allows for the measurement of other concepts of democracy and hopefully the improvement of the DB.Footnote 9 The main aim of the open structure is high replicability and transparency as well as the stimulation of ongoing theoretical and empirical debates about democracy.

Notes

Of course, several other measures of democracy exist. However, mainly due to their restrictions in terms of longitudinal availability, the indices of Hadenius (1992), Arat (1991), Coppedge and Reinicke (1988), Bollen (1980), Humana (1992), Gasiorowski (1990), and Alvarez et al (1996) (to give only some prominent examples) are not widely used in the empirical research of democracy. In addition, the criticisms levelled against the ‘big three’ (Polity, Freedom House, Vanhanen) concern these indices to different degrees as well.

These indices are appropriate to distinguish democratic regimes from non-democratic regimes, but they are not designed to measure the quality of established democracies. Even though we would intuitively distinguish the quality of democracy in Italy under Silvio Berlusconi, or the United States under George W. Bush from Finland's democracy under Matti Vanhanen, all three countries rank highest in these measures of democracy.

There are several other recent projects that aim at measuring the quality of democracy. The democratic audit (Beetham, 1994) provides a democracy assessment for experts and citizens. Strictly speaking, this project does not allow for international comparisons. The New Index of Democracy (NID) (Lauth, 2006) goes beyond minimalist concepts of democracy by including the dimension of democratic control. However, it is partly based on existing, criticised measures. The Democracy Ranking (Campbell, 2008) provides a ranking of the quality of democracy of about 100 countries for 2001/2002 and 2004/2005. The quality of democracy is measured using ten indicators (including Freedom House) that indicate the quality of politics and the quality of society (e.g., economic performance or ecological performance). The Sustainable Governance Indicators (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2009) measure the performance of OECD states. They focus on the quality of democracy as well as on the quality of democratic performance and combine expert ratings and official statistics. Stoiber and Abromeit (2006) provide a measure of democracy that takes contextual factors into account. Several other projects exist that have not yet provided disposable data (Diamond and Morlino, 2004; Foweraker and Krznaric, 2001) or that do not serve scientific purposes, such as the Everyday Democracy Index or the democracy scores of the Economist Intelligence Unit.

It is important to discern freedom rights from political rights. The latter are subject to the idea of equality (Rawls, 1971). Furthermore, due to the middle-range concept of the DB, social rights are not included (e.g., Marshall, 1974).

In the research on democratisation, governmental capability is often discussed in terms of interference with illegitimate actors (e.g., military, clergy; Merkel et al, 2003). Although we are focusing on established democracies, we assume that such actors are not present (at least their influence cannot be measured). Furthermore, we concentrate on intra-state constraints on implementation. Of course, globalisation has an impact on the quality of democracy. However, whether this impact is positive (e.g., through a growing room for manoeuvre) or negative (e.g., in terms of a loss of transparency and democratic accountability) is disputed (Guillén, 2003). With the DB, the diverging positions can be examined empirically but only when globalisation constraints are not included in the measure.

These criteria (FH-scores <1.5 and Polity-scores > 8 for the whole time span between 1995 and 2005; more than 250,000 inhabitants) apply to thirty-four countries: Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Barbados, Belgium, Canada, Cape Verde, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Malta, Mauritius, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and the United States. However, Cape Verde, Bahamas, Barbados, and Mauritius lacked data and were therefore deleted (for further information, see Bühlmann et al, 2011c and www.democracybaromter.org).

In order to measure variations in the quality of democracy properly, the relationships between principles, functions, components, and sub-components have to be translated into aggregation rules that fit the hierarchical concept of our theory. Our aggregation rule is therefore based on the following six basic assumptions: (1) Equilibrium is regarded as a positive feature. It indicates that (at a certain level), the elements of quality of democracy are in balance. Because the assumption of the underlying theory is that the best democracy is one in which all elements show a maximum performance, and the worst is one in which all elements show a minimum of performance, this is justified. (2) Since we are dealing in the framework of the ‘blue print countries’ with democracies, we cannot apply the simple and strict rule of necessary condition. Instead, a modification that allows for compensation of poor quality in one element by better quality in another element, is introduced. (3) Compensation, however, cannot result in full compensation (substitutability). The larger the disequilibrium, the lesser the compensation. Thus, disequilibrium must be punished relative to equilibrium. (4) Punishment for equal degrees of disequilibrium should be punished equally, and larger disequilibrium more than smaller disequilibrium. This implies progressive discount the larger the disequilibrium. (5) From this, it follows that punishment is disproportional and that the measure does not follow the rule of the mean but rather progression. (6) Increase in quality is progressive, but with diminishing marginal returns. We assume that, from a certain level on, an increase in quality in one or more elements boosts the quality of democracy, whereas above a certain quality, increases in quality are smaller. Thus, the measure should be progressive and should consider diminishing marginal utility in the increase of quality of democracy when a higher level is reached. In order to achieve progression, multiplication has been applied. In order to achieve diminished marginal returns, we apply an Arctan function: Value of a function=(arctan(component1*component2)*1.2/4000)*80. When there are three elements, we use the mean of the pairwise values, i.e.: Value of a principle={[(arctan(component1*component2)*1.2/4000)*80]+[(arctan(componentc1*component3)*1.2/4000)*80]+[(arctan(component2*component3)*1.2/4000)*80]}/3. The formula is more complex when there are values below 0. A more detailed description of our aggregation can be found in Bühlmann et al, 2011c and in the methodological handbook at www.democracybarometer.org.

One could, for instance, go back to more minimalist conceptions of democracy and take only freedom as the basic principle of democracy. On the other hand, employing a more maximalist conception of democracy, indicators that measure the output dimension of democracy could be added and combined to create a new measure of the quality of democracy.

References

Abromeit, H. (2004) ‘Die messbarkeit von demokratie: zur relevanz des kontextes’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift 45 (1): 73–93.

Altman, D. and Pérez-Liñán, A. (2002) ‘Assessing the quality of democracy: Freedom, competitiveness and participation in eighteen Latin American countries’, Democratization 9 (2): 85–100.

Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J.A., Limongi, F. and Przeworski, A. (1996) ‘Classifying political regimes’, Studies on Comparative International Development 31 (2): 1–37.

Arat, Z.F. (1991) Democracy and Human Rights in Developing Countries, Boulder: Lynne Riener.

Arndt, C. and Oman, C. (2006) Uses and Abuses of Governance Indicators, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Banducci, S.A., Donovan, T. and Karp, J.A. (2004) ‘Minority representation, empowerment, and participation’, The Journal of Politics 66 (2): 534–556.

Barber, B.R. (1984) Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bartolini, S. (1999) ‘Collusion, competition, and democracy’, Journal of Theoretical Politics 11 (4): 435–470.

Bartolini, S. (2000) ‘Collusion, competition and democracy: Part II’, Journal of Theoretical Politics 12 (1): 33–65.

Beetham, D. (ed.) (1994) Defining and Measuring Democracy, London: Sage.

Beetham, D. (2004) ‘Freedom as the foundation’, Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 61–75.

Berlin, I. (2006) Freiheit: Vier Versuche, Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2009) Sustainable Governance Indicators. Policy Performance and Executive Capacity in the OECD, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Bollen, K.A. (1980) ‘Issues in the comparative measurement of political democracy’, American Sociological Review 45 (2): 370–390.

Bollen, K.A. and Paxton, P. (2000) ‘Subjective measures of liberal democracy’, Comparative Political Studies 33 (1): 58–86.

Bühlmann, M. (2009) ‘The Beauty and the Beast? A tale of democratic crises and globalization’, Paper presented at the ECPR-panel on ‘Challenges to comparative politics’ at the International Political Science Association Congress, 12–16 July, Santiago de Chile.

Bühlmann, M. (2011) ‘The quality of democracy; crises and success stories’, Paper presented at the IPSA-ECPR joint conference, 16–19 February, Sao Paolo.

Bühlmann, M. and Kunz, R. (2011) ‘Confidence in the judiciary: Comparing the independence and legitimacy of judicial systems’, West European Politics 34 (2): 317–345.

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L. and Wessels, B. (2008) ‘Wie lässt sich demokratie am besten messen?’ Politische Vierteljahresschrift 49 (1): 1–9.

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Giebler, H., Müller, L. and Wessels, B. (2011a) ‘Demokratiebarometer – ein neues instrument zur Messung von Demokratiequalität’, Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft (forthcoming).

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L. and Wessels, B. (2011b) Democracy Barometer. Codebook for Blueprint Dataset Version 1, Aarau: Zentrum für Demokratie.

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L. and Wessels, B. (2011c) Democracy Barometer. Methodology, Aarau: Zentrum für Demokratie.

Bühlmann, M., Germann, M. and Vatter, A. (2011d) ‘Varieties of democracies: Lijphart's Democratic Quality Thesis revisited’, Paper presented at the EPSA Congress, 16–20 June, Dublin.

Bühlmann, M., Vatter, A., Dlabac, O. and Schaub, H.P. (2009) ‘Demokratiequalität im subnationalen Labor’, Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 40 (2): 454–467.

Cain, B., Dalton, R.J. and Scarrow, S. (eds.) (2003) Democracy Transformed? Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, D.F.J. (2008) The Basic Concept for the Democracy Ranking of the Quality of Democracy, Vienna: Democracy Ranking.

Chanley, V.A., Rudolph, T.J. and Rahn, W.M. (2000) ‘The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis’, The Public Opinion Quarterly 64 (3): 239–256.

Cingranelli, D.L. and Richards, D.L. (1999) ‘Respect for human rights after the end of the Cold War’, Journal of Peace Research 36 (5): 511–534.

Coppedge, M. and Reinicke, W. (1988) ‘A Scale of Polyarchy’, in R. Gastil (ed.) Freedom in the World: Political Rights and Civil Liberties 1987–1988, New York: Freedom House, pp. 101–128.

Dahl, R.A. (1956) A Preface to Democratic Theory, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dahl, R.A. (1998) On Democracy, New Haven: Yale University Press.

de Tocqueville, A. ([1835] 1997) Über die Demokratie in Amerika, Stuttgart: Reclam.

Diamond, L. and Morlino, L. (2004) ‘The quality of democracy: An overview’, Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 14–25.

Elkins, D.J. (1974) ‘The measurement of party competition’, American Political Science Review 68 (3): 682–700.

Elster, J. (1988) ‘Consequences of constitutional choice: Reflections on Tocqueville’, in J. Elster and R. Slagstad (eds.) Constitutionalism and Democracy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 81–101.

Etzioni, A. (1968) The Active Society, London: Collier-McMillan.

Ferreres-Comella, V. (2000) ‘A Defense of Constitutional Rigidity’, in P. Comanducci and R. Guastine (eds.) Analyses and Right, Turin: Biappichelli Publisher, pp. 45–68.

Fishkin, J. (1991) Democracy and Deliberation: New Directions for Democracy Reform, New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Foweraker, J. and Krznaric, R. (2001) ‘How to construct a database of liberal democratic performance’, Democratization 8 (3): 1–25.

Fraenkel, E. (ed.) (1962) Staat und Politik, Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer.

Freitag, M. and Bühlmann, M. (2009) ‘Crafting trust: The role of political institutions in a comparative perspective’, Comparative Political Studies 42 (12): 1537–1566.

Gasiorowski, M.J. (1990) ‘The political regimes project’, Studies in International Development 25 (1): 109–125.

Gibson, J.L. (2006) ‘Judicial Institutions’, in R.A.W. Rhodes, S.A. Binder and B.A. Rockman (eds.) Political Institutions, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 514–534.

Graber, D. (2003) ‘The media and democracy: Beyond myths and stereotypes’, Annual Review of Political Science 6 (1): 139−–160.

Guillén, M.F. (2003) ‘Is globalization civilizing, destructive or feeble? A critique of five key debates in the social science literature’, Annual Review of Sociology 27: 235–260.

Habermas, J. (1992) Faktizität und Geltung: Beiträge zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des Demokratischen Rechtsstaates, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, J. (2001) Between Facts and Norms, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hadenius, A. (1992) Democracy and Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hadenius, A. and Teorell, I. (2005) ‘Assessing alternative indices of democracy’, IPSA: Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper series No. 6.

Harmel, R. and Robertson, J.D. (1986) ‘Government stability and regime support: A cross-national analysis’, The Journal of Politics 48 (4): 1029–1040.

Holden, M. (2006) ‘Exclusion, Inclusion, and Political Institutions’, in R.A.W. Rhodes, S.A. Binder and B.A. Rockman (eds.) Political Institutions, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Humana, C. (1992) World Human Rights Guide, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Islam, R. (2006) ‘Does more transparency go along with better governance?’ Economics and Politics 18 (2): 121–167.

Kaufmann, D. and Kraay., A. (2008) ‘Governance indicators: Where are we, where should we be going?’, Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 8212.

Keane, J. (2009) The Life and Death of Democracy, London/New York: Simon & Schuster.

Keith, L.C. (2002) ‘Constitutional provisions for individual human rights (1977–1996): Are they more than mere ‘window dressing?’’, Political Research Quarterly 55 (1): 111–143.

Kriesi, H., Bühlmann, M., Cederman, L., Esser, F., Merkel, W. and Papadopoulos, Y. (2007) ‘Challenges to democracy in the 21st century’, National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) Position paper, Zurich: NCCR-Democracy.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Pop-Eleches, C. and Shleifer, A. (2004) ‘Judicial checks and balances’, Journal of Political Economy 112 (2): 445–470.

Lauth, H.J. (2006) ‘Die qualität der demokratie im interregionalen vergleich: probleme und entwicklungsperspektiven’, in G. Pickel and S. Pickel (eds.) Demokratisierung im internationalen Vergleich: Neue Erkenntnisse und Perspektiven, Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

Lijphart, A. (1997) ‘Unequal participation: Democracy's unresolved dilemma’, American Political Science Review 91 (1): 1–14.

Linz, J.J. and Stepan, A. (1996) Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America and Post-Communist Europe, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Locke, J. ([1689] 1974) Über die Regierung, Stuttgart: Reclam.

Manin, B., Przeworski, A. and Stokes, S.C. (1999) ‘Elections and Representation’, in A. Przeworski, S.C. Stokes and B. Manin (eds.) Democracy, Accountability, and Representation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 29–54.

Mansbridge, J. (1999) ‘Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent Yes’, Journal of Politics 61 (3): 628–657.

Marshall, T.H. (1974) Class, Citizenship and Social Development, New York: Greenwood.

Merkel, W., Puhle, H.-J., Croissant, A., Eicher, C. and Thiery, P. (2003) Defekte Demokratien. Band 1: Theorie, Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Merkel, W. and Giebler, H. (2009) ‘Good and bad quality: The multiple worlds of democracy within the OECD’, Paper presented at the workshop ‘Competing approaches to assessing democracy’ at the International Political Science Association Congress, 12–16 July, Santiago de Chile.

Meyer, T. (2005) Theorie der Sozialen Demokratie, Wiesbaden: VS.

Meyer, T. (2009) Was ist Demokratie? Eine diskursive Einführung, Wiesbaden: VS.

Michels, R. ([1911] 1966) Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy, New York: Free Press.

Müller, L. and Wüest, B. (2010) ‘Can mass media mobilize and empower voters in elections? A multi-level analysis of established democracies’, Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Political Science Association, 7–8 January, Geneva, Italy.

Munck, G. and Verkuilen, J. (2002) ‘Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: Evaluating alternative indices’, Comparative Political Studies 35 (1): 5–34.

O’Donnell, G. (1994) ‘Delegative democracy’, Journal of Democracy 5 (1): 55–70.

O’Donnell, G. (2004) ‘Why the rule of law matters’, Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 32–46.

Pateman, C. (1970) Participation and Democratic Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paxton, P., Bollen, K.A., Lee, D.M. and Kim, H.J. (2003) ‘A half-century of suffrage: New data and a comparative analysis’, Comparative International Development 38 (1): 93–122.

Powell, G.B. (2004) ‘Political representation in comparative politics’, Annual Review of Political Science 7: 273–296.

Putnam, R. (1993) Making Democracy Work, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rawls, J.A. (1971) A Theory of Justice, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Robinson, J.A. (2006) ‘Economic development and democracy’, Annual Review of Political Science 9 (1): 503–527.

Roller, E. (2005) The Performance of Democracies: Political Institutions and Public Policy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rudolph, T.J. and Evans, J. (2005) ‘Political trust, ideology, and public support for government spending’, American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 660–671.

Rueschemeyer, D. (2004) ‘Addressing inequality’, Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 76–90.

Sartori, G. (1987) The Theory of Democracy Revisited, Chatham: Chatham House Publishers.

Saward, M. (1998) The Terms of Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Schneider, A. (2003) ‘Decentralization: Conceptualization and measurement’, Studies in Comparative International Development 38 (3): 32–56.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1950) Kapitalismus, Sozialismus und Demokratie, Bern: Francke.

Stiglitz, J.E. (1999) ‘On Liberty, the Right to Know, and Public Discourse: The Role of Transparency in Public Life’, Oxford Amnesty Lecture, 27 January.

Stoiber, M. and Abromeit, H. (2006) ‘Measuring democracy: The inclusion of the context’, Paper presented at the 64th Annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, 20–23 April, Chicago USA.

Talmon, J.L. (1960) The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy, New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Tavits, M. (2006) ‘Party system change: Testing a model of new party entry’, Party Politics 12 (1): 99–119.

Teorell, J. (2003) ‘Linking social capital to political participation: Voluntary associations and networks of recruitment in Sweden’, Scandinavian Political Studies 26 (1): 49–66.

Teorell, J. (2006) ‘Political participation and three theories of democracy: A research inventory and agenda’, European Journal of Political Research 45 (5): 787–810.

Teorell, J., Sum, P. and Tobiasen, M. (2007) ‘Participation and Political Equality: An Assessment of Large-Scale Democracy’, in J.W. Van Deth, J. Ramon Montero and A. Westholm (eds.) Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, London: Routledge, pp. 384–414.

Urbinati, N. and Warren, M.E. (2008) ‘The concept of representation in contemporary democratic theory’, Annual Review of Political Science 11: 387–412.

Wolbrecht, C. and Campbell, D.E. (2007) ‘Leading by example: Female Members of Parliament as political role models’, American Journal of Political Science 51: 921–939.

Young, I.M. (1999) ‘State, Civil Society, and Social Justice’, in I. Shapiro and C. Hacker-Cordon (eds.) Democracy's Value, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 141–162.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bühlmann, M., Merkel, W., Müller, L. et al. The Democracy Barometer: A New Instrument to Measure the Quality of Democracy and its Potential for Comparative Research. Eur Polit Sci 11, 519–536 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.46

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2011.46