Abstract

This research examines recent electoral reform in French politics, and whether such reforms have served to minimize the overall impact of the earlier passage of gender parity law in 2000. As such, this is a study of how party elites often take steps to thwart any changes in the status quo that will endanger their own existing advantage or position. Specifically, we examine the increase in the number of two-round plurality districts for the Senate and the change from nationwide to regional districts for elections to the European Parliament (EP). Analysis of the 2001, 2004, 2008 and 2011 Senate elections suggests that the plurality method resulted in fewer women being elected to office, as compared with those Senate districts that used a closed-list proportional method, especially as a greater number of Senate districts began using the plurality method after the 2003 Raffarin reforms. Examining the 2004 and 2009 EP elections, we also find that the change to eight regional districts had an adverse effect on the election of female MEPs, primarily because fewer women were at the head of the regional party lists. Party proliferation in the 2004, 2008 and 2011 Senate elections also served to reduce the number of women elected in these races.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The push for increased representation of women had been building for several decades in French politics, culminating in the passage of a parity law in 2000 (Henry, 1995; Haase-Dubosc, 1999; Allwood and Wadia, 2000; Jenson and Valiente, 2003). This drive was spurred, in part, by France’s relative low numbers of female politicians compared with most of its European neighbors.Footnote 1 However, despite the introduction of the parity law, the number of female politicians in France has only risen slightly over the past decade, and has actually shown signs of stagnation in recent Senate and European Parliament (EP) elections, despite some gains in the National Assembly and municipal elections. We examine why parity did not have the marked impact that its supporters had hoped, by testing the hypothesis that other electoral reforms, which occurred in France shortly after the introduction of this parity law in 2000, had an adverse effect on the election of more females to elected office. We also examine the effect of informal party practices, such as the headship of party lists and party proliferation, on the election of female politicians in the post-parity era.

Parity Reform

Although French parity movement emerged in the early 1990s, it was not until after the National Assembly elections of 1997 that the government agreed to revise the Constitution and adopt parity legislation. In the 2000 session of the French National Assembly, a parity law was passed, requiring all parties to present an equal number of female and male candidates in the party lists for those elections conducted via proportional representation (PR) – EP, a majority of seats to the national Senate, and municipal and regional elections (French Senate, 2000). For plurality elections, specifically, the National Assembly elections, local elections and the remaining portion of the Senate seats, there was no legal mandate to present equal numbers of male and female candidates. However, there were financial incentives in the form of substantial penalties for those parties that failed to comply.Footnote 2 The expectations were such that the combination of these legal obligation and financial incentives would lead the parties to nominate more female candidates, and the number of female politicians in France would increase. (For a full description of parity reform in France, see Gaspard, 1998, 2001; Baudino, 2000, 2005; Mazur Amy, 2001, 2003; Sineau, 2001; Murray, 2004; Scott, 2005; Opello, 2006.)

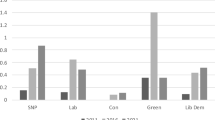

This gender parity law was first implemented in the municipal elections of March 2001, which resulted in the proportion of women town councilors rising from 25.7 per cent to 47.5 per cent in municipalities with more than 3500 residents (Bird, 2002). Similarly, in the elections to the Senate in September of 2001, those 74 races in which the parity law was applicable (those using PR) resulted in an increase from 5 to 20 female senators. In those 28 remaining Senate contests where parity was not directly applicable (those using a two-round plurality (TRP) system), the number of women stayed the same, at two. In the elections to the French National Assembly, the number of female deputies increased slightly from 63 (10.9 per cent) in 1997 to 71 (12.3 per cent) in 2002. From the standpoint of gender parity, the first set of post-parity elections appeared to be moderately successful. However, these initial gains in female representation appear to have stagnated. As displayed in Figures 1 and 2, the percentage of women elected to the National Assembly has continued to rise, but only modestly so. However, the most recent EP and the 2008 Senate elections have actually shown a slight decrease in the percentage of women elected to office. As a possible explanation, we now turn to other electoral reforms that were adopted shortly after the parity law – the Raffarin reforms of 2003.

Percentage of women elected to the French National Assembly and Senate, 1997–2011. Sources: French Ministry of the Interior (2002, 2004a, 2004b, 2007, 2008); French Senate (2001, 1998); French National Assembly (1997).

Percentage of women in the EP, France and the EU, 1979–2009. Source: European Parliament (2009a, 2009b).

Electoral Reform

In 2003, Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin, as leader of the UMP (Union pour un Mouvement Populaire), initiated a series of electoral reforms that had indirect consequences on parity reform. These laws changed the method by which elections to the Senate and the EP are conducted.Footnote 3 Before these reforms, elections to the EP were conducted by PR, with the entire nation as the sole constituency, with national party lists. However, since 2003, there have been eight regional districts with distinct party lists of EP candidates in each district. Although these districts still use a PR method, this change can reduce the chances of female candidates being elected. Specifically, although parity law requires party lists to alternate men and women, a ‘zippering’ system (Freedman, 2002), a majority of party lists have been headed by male candidates. In those situations where a party receives only one or an uneven number of seats in a district, an imbalance occurs in the number of male and female candidates who actually fill those seats within their party. Although this imbalance is slight with one national constituency, as was the case in the 1999 elections to the EP, the potential for such bias against female candidates increases as the number of districts increases.

The reforms for the Senate increased the number of districts that use a TRP system, as compared with the closed-list PR method.Footnote 4 The electoral system for this body had traditionally used a plurality method only for those districts with fewer than three seats to be chosen – approximately one-third of all seats (37 per cent in the 2001 Senate elections). However, the Raffarin reforms raised this threshold to three seats per district, resulting in 35 per cent of all senators being chosen in plurality districts in the 2004 elections, and a markedly increased figure of 65 per cent in the 2008 elections (Sénat, www.senat.fr/evenement). As such, the effect of this reform did not really become apparent until the later 2008 elections,Footnote 5 although the percentage of closed-list proportional method (CPR) was much higher in 2011.

Previous Research

We are assuming that the implementation of party list quotas for women does enhance women’s representation in these countries, based on previous research (Kolinsky, 1991; Phillips, 1991; Jones, 1996, 1998, 2004, 2009; Squires and Wickham-Jones, 2001; Lovenduski, 2005; Kittilson, 2006; Dahlerup, 1988; Stockemer, 2008a, 2008b; Krook, 2009). Those countries in the Americas and Europe with the highest percentage of women in their national legislature have some type of quota provision, either in the form of a mandated percentage of each party’s nominees or reserved seats. Additional research emphasizes that mandatory or voluntary gender quotas are most effective in those countries that use PR with large districts (Jones and Navia, 1999; Freedman, 2002; Jones, 2004). With the exception of Inglehart and Norris (2003), most cross-national studies have shown that women’s representation is higher under PR than under plurality systems (Champman, 1993; Rule and Zimmerman, 1994; Matland and Studlar, 1996; Caul, 1999; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, 2005). Party officials are more likely to nominate women (and other political newcomers) in large, multi-member districts, rather than in smaller or single-member districts where they have a strong incentive to push for the re-election of male incumbents (Thiébault, 1988; Matland and Dwight Brown, 1992; Gaspard, 1998; Sineau, 2001; Reynolds et al, 2005).

However, even a system of PR can be used to circumvent parity laws. Opello (2006) and Dahlerup (1988) emphasize that the extent to which PR favors women depends not only on how many women are nominated, but where they are placed on party lists. Clearly, placing males at the head of the party list works to their advantage. Fréchette et al (2008) and Bird (2002, 2003) also describe the process of ‘party proliferation’ in France. In this scenario, incumbent males within a particular party in France recognized that after the 2000 parity law, in the upcoming PR districts, they would have to relinquish the second, and perhaps the fourth, place on the party list to a female candidate. Therefore, all of these male incumbents could only be re-elected if their party picked up seats in the district. As such, one or several of them strategically formed a new party list with their names at the top. Fréchette et al (2008) found such party proliferation in 11 of the 29 PR districts during the Senate elections of 2001 and 2004.

As such, an important set of explanations for the representation of women is the role of the political party in fulfilling, or subverting, the implementation of candidate gender quotas (Krook, 2006). A lack of will among political party elites to apply quota provisions can be crucial. In some cases, elites simply do not comply with the quota (Appleton and Mazur, 1993; Htun and Jones, 2002); in others, they expend a great deal of time circumventing the spirit of the law, often by creating new political institutions to which the quota does not apply or by expanding the restrictions on the application of the law (Jimenez Polanco, 2001).

It is quite possible that the main intent of the Raffarin reforms of 2003 were to reverse the rule changes after a period of cohabitation. However, these changes also worked to the disadvantage of female candidates by diminishing the number of PR districts for the Senate and also by creating smaller and regional districts for the EP elections. Furthermore, we expect that informal actions taken by the parties to continue the male dominance of the placement of party lists and party proliferation worked to the disadvantage of women, even in PR districts.

Much of the previous research on the impact of parity has centered on the 2002 and 2007 elections to the National Assembly (Murray, 2004, 2008a, 2008b, 2009; Baudino, 2005; Southwell and Smith, 2007; Fréchette et al, 2008). In plurality districts, the factors that have also been deemed to have hindered the election of female candidates include: (i) incumbency advantage (Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, 2005); (ii) the party strategy of nominating female candidates in marginally unsafe districts (Murray, 2008a); and (iii) membership in a center-right party (Norris, 1993; Caul, 2001). However, National Assembly elections were least affected by the 2000 parity legislation, as discussed above, with only financial incentives for the nomination of women. For this reason, we center on elections to the EP and the Senate. We now turn to an analysis of the election data by comparing the pre- and post-Raffarin reform elections to these two legislative bodies.

Parity and Pre- and Post-Raffarin Reform Elections

As indicated by Table 1, women have had an increasingly difficult time getting elected to the Senate, especially in 2008, when the bulk of seats were decided in TRP districts. The contrast between plurality (TRP) and proportional (CPR) districts is quite striking, especially in the light of the very low number of CPR districts in 2008. Although the increased success of female candidates in 2011 is apparent, this result appears to be affected by the increased number of CPR districts in that particular year, that is, the cycle of French Senate elections rotates alphabetically, and the latter third tends to be more urban districts with more seats per districts, and hence the greater use of CPR in 2011. The variation in female electoral success across these years with differing numbers of CPR districts thus underscores the impact of the Raffarin reforms, which reduced the overall number of CPR districts for Senate elections.

Party Proliferation

The phenomenon of ‘party proliferation’ in the 1998 and 2001 Senate elections was analyzed by Fréchette et al (2008) – a scenario where party members bolt from their own party to form a new, temporary party, presumably to bypass parity requirements for CPR districts. By such a strategy, two male incumbents can avoid the parity requirements for PR districts that require alternation of male and female candidates on their party lists. Our examination of the most recent Senate and EP elections confirms the findings of Fréchette and colleagues for the most recent Senate elections, but not for the elections to the EP. In all four Senate elections (2001, 2004, 2008 and 2011), there were 18 districts out of 58 total CPR districts in which certain members of the center-right party (UMP) ran instead as a head of an alternative party list, usually called Divers Autres (Other Diverse), or even in 2011 with the same coalition name (LMAJ). In each of these 18 districts, the result was the election of two male UMP Senators, rather a second-place female on the UMP party list, as required by the parity law. Despite the ballot identifying them as members of different parties, their official Senate biography listed these senators as members of the UMP party (French Senate, 2004). There were many additional examples of unsuccessful male candidates attempting this strategy as well. Although it is difficult to ascertain the impact of such actions on the number of females elected to the Senate, a conservative estimate is that 17 more female senators would have been elected to the French Senate between 2004 and 2011, if this party proliferation had not have occurred.Footnote 6

Elections to the EP

The change to eight regional districts for EP elections also reduced the number of female MEPs. For example, the Socialist Party captured 31 seats in the 2004 EP elections. If the country had been one nationwide district, as in 1999, at least 15 of these Socialist MEPs would have been required to be female by parity law. However, the disaggregation of the Socialist vote across the country meant that, in some of these eight districts, an uneven number of seats were won by the Socialists, resulting in a male bias.Footnote 7 The actual Socialist delegation to the EP, following the 2004 election, was 18 male MEPs and 13 female MEPs, a loss of two potential female MEPs. The cumulative effect of such male bias for all parties was a net loss of six female MEPs in 2004.

A similar pattern occurred for both the UMP and the Socialist parties in the 2009 EP election, but this male bias was offset by two smaller parties, the Movement for Democracy (MoDem) and the Greens (Verts) who, in contrast, had a female candidate heading their party list in three out of the eight regional districts. Thus, the change in the electoral rules had little impact on the number of women elected to the EP in 2009. However, both these elections underscore the importance of the headship of party lists for the representation of women under a PR system (Table 2).

We can now estimate how female candidates might have fared in these post-2001 elections, if the previous electoral rules had been in place, as well as the impact of party proliferation, as shown in Table 2. First, we examine those Senate districts with three seats at stake, that is, those that began using a plurality system in the 2004 election after the Raffarin reforms. Looking at these 24 such districts (7 in 2004, 9 in 2008 and 8 in 2011), we can ‘re-run’ the races in these districts under the previously used CPR system to determine whether the prior rules might have altered the gender balance of the Senate delegation from each of these districts. We make the assumption that the voters (primarily municipal councilors) would have voted in the same manner, along party lines. The results suggest that more women would have been elected if the Raffarin reforms had not been adopted and the previous PR method had been used in these three-seat districts. For example, in the Senate district of Indre et Loire in 2011, the left-leaning preferences of voters resulted in the election of two members of the Socialist Party and one Communist Party member – all men. Had this district used the 2001 CPR method, the parity law would have required the Socialist Party to have a party list with at least one woman among the top three spots on their party list. Therefore, a minimum of one female Socialist member would have been elected, instead of the actual result of three male candidates in this district. In all of the four such districts in 2011, a similar scenario occurred, resulting in the loss of four potential female Senators, two seats in the UMP and one each in the Socialist and Diverse Left (DVG) Party.Footnote 8 For the 2004 and 2008 Senate elections, similar results occurred, but were even more marked because there were more TRP contests in these election years – a loss of seven potential female Senators both in 2004 and 2008, primarily because of the switch from proportional to plurality electoral rules.

This table also incorporates the similar estimates for EP elections, and party proliferation in the 2004, 2008 and 2011 elections. That is, we looked at the actual vote totals in all these elections, but assumed that the EP elections would have stayed nationwide, and that party members would not have been able to temporarily defect from their own party in CPR districts. The cumulative effect of these three phenomena (the switch to a greater number of TRP Senate districts, regional EP districts and party proliferation) is remarkable. Had the previous electoral rules been in effect, and had parties been prevented from running two of its candidates on different party lists, it is likely that a substantially increased number of women would have been elected to office in France.

These estimates are quite conservative, as we did not take into account the impact of the typical pattern of French parties in placing male candidates at the head of the party list. An analysis of the most recent 2011 Senate elections suggests that even if half of the 60 party lists of winning parties in the CPR districts had been headed by a woman, instead of the actual 4, 13 more women would have become senators.

Summary and Conclusions

Clearly, there are other possible explanations for this modest increase in the number of women in French politics. Incumbency advantage, as well as the use of TRP in rural districts, may have contributed to the slower-than-expected entry of women into French electoral politics. The Socialist Party has tended to choose more female candidates than other French parties, and therefore their electoral setbacks in the 2000s may have been a factor. However, the ‘rules of the game’ are clearly an important variable. The Raffarin reforms had a definitive impact, and most likely were adopted with at least partial knowledge of the electoral consequences for parity, and certainly the headship bias and party proliferation did not occur unwittingly. Prime Minister Pierre Raffarin served from 2002 to 2005, as head of the center-right party UMP. The parliamentary debate over these electoral reforms indicates that one of the reasons for the adoption of these reforms was to increase turnout in EP elections by offering candidates with closer local ties to the voters.

However, it is a bit more difficult to be sanguine about the increase in the number of plurality districts for Senate elections, as Senators were quite open in their opposition to parity law. In 2000, after the National Assembly approved the parity law, 60 senators challenged it before the Constitutional Council, which upheld the law. These analyses suggest that France engaged in two inter-related types of electoral reform during the past decade – the introduction of parity and the structural reform of its Senate and EP elections – and the latter served to dampen the effect of parity. The Raffarin electoral reforms of 2003 appear to have reduced the potential for the election of more female politicians, by the greater use of plurality districts in Senate elections. In addition, the change to regional districts for elections to the EP created a situation in which male bias in party lists, even under PR, worked to the disadvantage of female candidates. This tendency to head party lists with male candidates also diminished the electoral chances of women in Senate PR districts. Party proliferation, although not widespread in Senate PR districts, also reduced the number of successful female Senate candidates.

These findings help to explain why parity law has resulted, after one decade, in only a modest increase in the number of female officeholders in France. This research underscores that quota provisions can be circumvented or modified considerably by other modifications of the electoral system or electoral law.

It appears that defenders of gender parity should push for a return to more proportionality in Senate elections, and consider whether the headship of party lists should come under greater scrutiny for all CPR districts, including the eight regional EP ones. The most recent parity legislation (December 2010), involving municipal elections, is not encouraging (Troupel, 2012). Reining in party proliferation would also be a difficult task, but unless some recognition of these varied obstacles to parity are made by the national legislature or the largest parties, the impact of French parity law will remain quite modest.

Notes

In 2001, with only 10.9 per cent female legislators, France was ranked second to the last among EU members.

These subsidies are more crucial to smaller parties; and in the first post-parity National Assembly election in 2002, only small parties nominated as many women as men. The UMP nominated only 20 per cent of all female candidates, and lost €4 million out of €25 million as result, but still won a majority in the National Assembly.

See French Senate (2003a). This 11 April 2003 law also modified the electoral method for regional councils, by the division of party lists into sections (corresponding to each district).

Loi No 2003-697 portant réforme de l’élection des sénateurs (French Senate, 2003b).

Approximately, one-third of Senate seats were up for election in 2004, many from larger districts, which used the PR method.

In 2001, these districts were Isère, Loire, Meurthe-et-Moselle and Français établis hors de France. In 2004, these districts were Essonne, Hauts de Seine, Paris, Seine Saint Denis and Var. In 2008, these districts were Gironde and Français établis hors de France. In 2011, these districts were Isère, Moselle, Nord, Paris, Hauts de Seine and Val d‘Oise.

For example, in both the Nord-Ouest and Ouest districts, the Socialists captured three seats, only one held by a woman.

These districts are: Guadeloupe, Haute Savoie, Saone et Loire, Sarthe, Somme, Vaucluse and Vendée for 2004; Calvados, Charente Maritime, Cotes d‘Armor, Cote d‘Or, Drome, Doubs, Eure, Eure et Loir and Gard for 2008; Guadaloupe, Indre et Loire, Loiret and Manche for 2011.

References

Allwood, G. and Wadia, K. (2000) Women and Politics in France 1958–2000. New York: Routledge.

Appleton, A. and Mazur, A.G. (1993) Transformation or modernization: The rhetoric and reality of gender and party politics in France. In: J. Lovenduski and P. Norris (eds.) Gender and Party Politics. Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 86–112.

Baudino, C. (2000) La Cause des Femmes à l‘Épreuve de son Institutionnalisation. Politix 133 (51): 81–112.

Baudino, C. (2005) Gendering the republican system: Debates on women’s political representation in France. In: J. Lovenduski (ed.) State Feminism and Political Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bird, K. (2002) Does parity work? Results from French elections. Feminist Studies 28 (1): 691–698.

Bird, K. (2003) Who are the women, where are the women, and what difference can they make? Effect of gender parity in the French municipal elections. French Politics 1 (3): 5–38.

Caul, M. (1999) Women’s representation in parliament. Party Politics 5 (4): 79–98.

Caul, M. (2001) Political parties and the adoption of candidate gender quotas: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Politics 63 (1): 1214–1229.

Champman, J. (1993) Politics, Feminism, and the Reformation of Gender. London: Routledge.

Dahlerup, D. (1988) From a small to a large minority: Women in scandinavian politics. Scandinavian Political Studies 11 (4): 275–298.

European Parliament. (2009a) Distribution of men and women (Europe). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/parliament/archive/elections2009/en/men_women_en.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

European Parliament. (2009b) Distribution of men and women (France). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/parliament/archive/elections2009/en/france_en.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

Fréchette, G., Maniquet, F. and Morelli, M. (2008) Incumbent’s interests and gender quotas. American Journal of Political Science 55 (4): 891–909.

Freedman, J. (2002) Women in the European parliament. Parliamentary Affairs 55 (1): 179–188.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2002) Résultats des Élections. http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Legislatives/elecresult_legislatives_2002/(path)/legislatives_2002/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2004a) Élections Éuropéennes du 13 Juin.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2004b) Élections Sénatoriales du 26 Séptembre. http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Senatoriales/elecresult__senatoriales_2004/(path)/senatoriales_2004/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2007) Résultats des Élections. http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Legislatives/elecresult__legislatives_2007/(path)/legislatives_2007/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2008) Résultats des Élections. http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Senatoriales/elecresult__senatoriales_2008/(path)/senatoriales_2008/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Ministry of the Interior. (2009) Résultats des Élections Européennes 2009. http://www.interieur.gouv.fr/Elections/Les-resultats/Europeennes/elecresult__europeennes_2009/(path)/europeennes_2009/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French National Assembly. (1997) Les Élections Législatives des 25 mai et 1er juin 1997. http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/connaissance/elections-1997.asp, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (1998) Élections Sénatoriales 1998. http://www.senat.fr/evenement/elections98/caractrist.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (2000) Loi n° 2000-493 du 6 juin 2000 tendant à favoriser l’égal accès des femmes et des hommes aux mandats électoraux et fonctions electives. http://www.senat.fr/dossierleg/pjl99-192.html), accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (2001) Élections Sénatoriales 2001. http://www.senat.fr/evenement/senatoriales_2001/index.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (2003a) Loi n° 2003-697 du 30 juillet 2003 portant réforme de l'élection des sénateurs. http://legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000430722, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (2003b) Loi n° 2000-493 du 6 juin 2000 tendant à favoriser l’égal accès des femmes et des hommes aux mandats électoraux et fonctions electives. http://legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000400185, accessed 3 March 2013.

French Senate. (2004–2011) Vos Sénateurs. http://www.senat.fr/elus.html, accessed 3 March 2013.

Gaspard, F. (1998) Parity: Why not? Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 9: 93–104.

Gaspard, F. (2001) The French parity movement. In: J. Klausen and C.S. Meier (eds.) Has Liberalism Failed Women? Assuring Equal Representation in Europe and the United States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haase-Dubosc, D. (1999) Sexual difference and politics in France today. Feminist Studies 25 (1): 183–210.

Henry, N. (1995) Gender parity in French politics. The Political Quarterly 66 (3): 177–180.

Htun, M.N. and Jones, M.P. (2002) Engendering the right to participate in decision-making: Electoral quotas and women’s leadership in Latin America. In: N. Craske and M. Molyneux (eds.) Gender and the Politics of Rights and Democracy in Latin America. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 32–56.

Inglehart, R. and Norris, P. (2003) Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jenson, J. and Valiente, C. (2003) Comparing two movements for gender parity: France and Spain. In: A.L. Banaszak, K. Beckwith and D. Rucht (eds.) Women’s Movements Facing the Reconfigured State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jimenez Polanco, J. (2001) La Representation Politique des Femmes en Amerique Latine: Une analyse compare. In: B. Marques-Pereira and P. Nolasco (eds.) La Représentation Politique des Femmes en Amérique Latine: une analyse comparée. Brussels, Belgium: L’Harmattan.

Jones, M.P. (1996) Increasing women’s representation via gender quotas: The Argentine ley de cupos. Women & Politics 16 (4): 75–99.

Jones, M.P. (1998) Gender quotas, electoral laws, and the election of women: Lessons from the Argentine provinces. Comparative Political Studies 31 (1): 3–21.

Jones, M.P. (2004) Quota legislation and the election of women: Learning from the Costa Rican experience. Journal of Politics 66 (4): 1203–1223.

Jones, M.P. (2009) Gender quotas, electoral laws, and the election of women: Evidence from the Latin American Vanguard. Comparative Political Studies 42 (1): 56–81.

Jones, M.P. and Navia, P. (1999) Assessing the effectiveness of gender quotas in open-list proportional representation electoral systems. Social Science Quarterly 80 (2): 341–355.

Kittilson, M.C. (2006) Challenging Parties, Changing Parliaments: Women and Elected Office in Contemporary Western Europe. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, Parliaments and Legislatures Series.

Kolinsky, E. (1991) Political participation and parliamentary careers: Women’s quotas in West Germany. Western European Politics 14 (1): 56–72.

Krook, M.L. (2006) Reforming representation: The diffusion of candidate gender quotas worldwide. Politics & Gender 2 (3): 303–327.

Krook, M.L. (2009) Quotas for Women in Politics: Gender and Candidate Selection Reform Worldwide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lovenduski, J. (2005) State Feminism and Political Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matland, R.E. and Dwight Brown, D. (1992) District magnitude’s effect on female representation in U.S. state legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly 17: 469–492.

Matland, R.E. and Studlar, D.T. (1996) The contagion of women candidates in single-member district and proportional representation electoral systems: Canada and Norway. Journal of Politics 58 (3): 707–733.

Mazur, A.G. (2001) Drawing lessons from the French parity movement. Contemporary French Civilization 25 (2): 201–220.

Mazur, A.G. (2003) Drawing comparative lessons from France and Germany. Review of Policy Research 20 (2): 491–523.

Murray, R. (2004) Why didn’t parity work? A closer examination of the 2002 election results. French Politics 2 (3): 347–362.

Murray, R. (2008a) The power of sex and incumbency: A longitudinal study of electoral performance in France. Party Politics 14 (5): 539–554.

Murray, R. (2008b) How a high proportion of candidates becomes a low proportion of députées: A new model to forecast women’s electoral performance in French legislative elections. French Politics 6 (2): 152–165.

Murray, R. (2009) Was 2007 a landmark or a letdown for women’s political representation in France? Representation 45 (5): 29–38.

Opello, K.A.R. (2006) Gender Quotas, Parity Reform, and Political Parties in France. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Phillips, A. (1991) Engendering Democracy. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Reynolds, A., Reilly, B. and Ellis, A. (2005) Electoral System Design: The New International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm, Sweden: International IDEA.

Rule, W. and Zimmerman, J.F. (1994) Electoral Systems in Comparative Perspective: Their Impact on Women and Minorities. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Schwindt-Bayer, L.A. and Mishler, W. (2005) An integrated model of women’s representation. Journal of Politics 67 (2): 407–428.

Scott, J.W. (2005) Parité! Sexual Equality and the Crisis of French Universalism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sineau, M. (2001) France. In: J. Ballington and A. Karam (eds.) Women and Parliament beyond the Numbers. Stockholm, Sweden: International IDEA.

Squires, J. and Wickham-Jones, M. (2001) Women in Parliament: A Comparative Analysis. Manchester, UK: Equal Opportunity Commission.

Stockemer, D. (2008a) Women’s representation: A comparison between Europe and the Americas. Politics 28 (2): 65–73.

Stockemer, D. (2008b) Women’s representation in Europe – A comparison between the National Parliaments and the European Parliament. Comparative European Politics 6 (4): 463–485.

Southwell, P. and Smith, C. (2007) Equity of recruitment: Gender parity in French National Assembly elections. The Social Science Journal 44 (1): 83–90.

Thiébault, J.-L. (1988) France: The impact of electoral change system. In: M. Gallagher and M. Marsh (eds.) Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective. London: Sage Publications.

Troupel, A. (2012) Entre Consolidation et Remise en Cause: Les Tribulations de la Loi sur la Parité depuis le 6 Juin 2000. Modern and Contemporary France. http://dx/doi.org/10.1080/09639489.2012.719492.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Southwell, P. Gender parity thwarted? The effect of electoral reform on Senate and European Parliamentary elections in France, 1999–2011. Fr Polit 11, 169–181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2013.4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2013.4