Abstract

Suspicion towards polls in France has come to a maximum after their failure in predicting Le Pen's qualification to the second round of the 2002 presidential election. Despite general satisfaction with polls in 2007, we show that their performance is in fact not better than that in 2002 according to some measures of poll accuracy. Even if the final order of arrival of the top four candidates has been predicted exactly by most polls, this is largely due to the important differences of scores among them. Estimates are still based on quite untouched techniques, and therefore suffer important bias in addition to classical margins of error.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

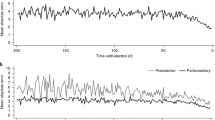

If, on the academic side, more and more national election studies have added some kind of pre-electoral survey (through panel studies mainly and rolling cross-section methodology), data on the issue of opinion evolution throughout the campaign are limited. Rolling cross-section surveys, which are designed for this specific purpose, are scarce (such a method has not been implemented in France yet) and often limited in the time span covered.

It should, however, not be forgotten that more than one hundred constituencies did not vote in the second round, all these constituencies having already been won by a right-wing landslide.

The idea was to increase VAT to decrease salary charges, following the German example.

We could also add the bias of polls for Chirac in 1995 (both Balladur and Jospin scores being significantly underestimated) and the failure of some polls in 1997, predicting a victory of the right, whereas the Socialists won a majority (Jérôme et al., 1999).

For more positive or balanced views of polls in France, we can refer to the classical volume of Frédéric Bon (1974) or to the more contemporary analysis of Patrick Lehingue (2007).

Although ISPOS announced a new poll each day (with one-third of its sample new each day), we chose here to take into consideration the ‘complete samples’ (hence two polls a week) to prevent excessive autocorrelation of the series.

Inversion in ranks exists for minor candidates, among those with a score of less than 2.5% of the vote. Villiers particularly suffered from an underestimation of his score when most extreme left candidates were overestimated.

We chose this method because different institutions conduct polls with different periodicity and because there more differences across different series of polls than within a series of polls with a short time span. The difference between this method and the more traditional method of collecting every poll during the last week of the campaign is, however, very small (a comparison is possible with Durand, 2008).

Defined by the absence of a systematic bias.

This technique is, however, not specific to France, the particularity of France being the inexistence of pure random sampling.

Although CATI polls would allow it more easily, we can also note that overseas territories are almost never taken into account. One again, the bias is probably limited though significant.

This survey is part of the project CSES-France, conducted with the support of the French agency for research. The survey is based on a CATI poll of 2,000 people, selected through random sampling with stratification. See http://www.cses.org to get a presentation of the study and more specifications on French data.

The Panel Electoral Français 2002 is a three-wave panel aiming to explain electoral behaviour for the presidential and legislative elections. A precise description of the study can be found on the website of the Centre des Données Socio-Politiques (http://www.cdsp.sciences-po.fr).

Kalman published a paper in 1960 that soon became famous in the area of autonomous or assisted navigation. This paper describes a recursive solution to the discrete-data linear filtering problem (Harvey, 1996). The Kalman filter is a set of mathematical equations that provides a means to estimate the state of a process, in a way that minimizes the mean of the squared error. It has been applied in political science particularly by Green et al. (1999) and Jackman (2005). The problem with Kalman filtering is that it minimizes only the stochastic component of polls’ error.

In this perspective, forecasting power could be estimated through the comparison of the margin of error of the estimates against those of ‘reasonable hypotheses’ on future outcomes. These hypotheses could be based on randomness (each candidate has the same vote probability function, with a mean equal to one divided by the number of candidates), theory (on equilibriums in two round elections for instance) or history (you know for instance that, on average, left-wing presidential candidates get together 45% of the votes during the Fifth Republic in the first round) or a combination of the three.

References

Blais, A. (2004) ‘Strategic Voting in the 2002 French Presidential Election’, in M. Lewis-Beck (ed.) The French Voter: Before and After the 2002 Elections, Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 93–109.

Bon, F. (1974) Les sondages peuvent-ils se tromper? Paris: Calmann-Lévy.

Boy, D. and Chiche, J. (1999) ‘La qualité des enquêtes d’intention de vote : le cas des régionales de 1998’, in Sofres (ed.) L’Etat de l’opinion, Paris: Seuil, pp. 237–253.

Cautrès, B. and Jadot, A. (2007) ‘L’(in)décision électorale et la temporalité du vote: le moment du choix pour le premier tour de l’élection présidentielle 2007’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 57 (3–4): 293–314.

Courtois, G. (2007) ‘Les sondages, pour le meilleur et pour le pire’, Revue Politique et Parlementaire, 1044: 155–162.

Curtice, J. and Sparrow, N. (1997) ‘How accurate are traditional quota opinion polls?’, Journal of the Market Research Society, 39: 433–448.

Dolez, B. and Laurent, A. (2007) ‘Une primaire à la française : la désignation de Ségolène Royal par le Parti socialiste’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 57 (2): 133–162.

Durand, C. (2008) ‘La méthodologie des sondages électoraux de l’élection présidentielle française de 2007, chroniques d’un problème recurrent’, Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 97: 5–17.

Durand, C., Blais, A. and Larochelle, M. (2004) ‘The polls in the 2002 French presidential election: an autopsy’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 68 (4): 602–622.

Garrigou, A. (2006) L’ivresse des sondages, Paris: La Découverte.

Gouriéroux, C. (1981) Théorie des sondages, Paris: Economica.

Green, D.P., Gerber, A.S. and De Boef, S.L. (1999) ‘Tracking opinion over time: a method for reducing sampling error’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 63: 178–192.

Harvey, A.C. (1996) Forecasting, Structural Time Series Models and the Kalman Filter, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jackman, S. (2005) ‘Pooling the polls over an election campaign’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 40 (4): 499–517.

Jérôme, B., Jérôme, V. and Lewis-Beck, M. (1999) ‘Polls fail in France: forecasts of the 1997 legislative election’, International Journal of Forecasting, 15: 163–174.

Lehingue, P. (2007) Subunda: coups de sonde dans l’océan des sondages, Paris: Editions du Croquant.

Marc, X. and Rivière, E. (2007) ‘Les sondages, entre interrogations et réhabilitation’, Revue Politique et Parlementaire, 1044: 148–154.

Mayer, N. (2002) Ces Français qui votent Le Pen, Paris : Flammarion.

Mayer, N. (2007) ‘Comment Nicolas Sarkozy a rétréci l’électorat Le Pen’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 57 (3–4): 429–445.

Mitofsky, W.J. (1998) ‘The polls — review: was 1996 a worse year for polls than 1948?’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 62 (2): 230–249.

Parodi, J.-L. (2002) ‘Les effets pervers d’une présélection annoncée’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 52 (5–6): 485–504.

Perrineau, P. and Ysmal, C. (eds.) (2003) Le vote de tous les refus, Paris: Presses de Sciences-Po.

Sauger, N. (2007) ‘Le vote Bayrou : l’échec d’un success’, Revue Française de Science Politique, 57 (3–4): 447–458.

Sauger, N., Brouard, S. and Emiliano, G. (2007) Les Français contre l’Europe? Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Taylor, H. (1995) ‘Horses for courses: how survey firms in different countries measure public opinion with different methods’, Journal of the Market Research society, 37 (3): 211–219.

Traugott, M.W. (2005) ‘The accuracy of the national preelection polls in the 2004 presidential election’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 69 (5): 642–654.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sauger, N. Assessing the Accuracy of Polls for the French Presidential Election: The 2007 Experience. Fr Polit 6, 116–136 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2008.6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2008.6