Abstract

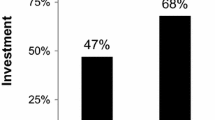

Economic voting studies have been dominated by the classic reward–punishment paradigm, in which voters vote for the incumbent under good economic performance, but against under bad. This paradigm works well when the economic issue is a valence issue, such as prosperity. However, it leaves out positional economic voting, in which the voter's place in the economic structure influences policy preference, and thus party preference. More precisely, we suggest that the better the economic location of voters in terms of assets, high-risk assets in particular, the more they will vote right, because the right promises a better return on their investments. We demonstrate this effect in French presidential election data, from three national surveys – 1988, 1995 and 2002. This assets effect well exceeds other economic effects tested, and does so under strong statistical controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The idea of ‘sociotropic economic voting’ was launched by Kinder and Kiewiet (1981).

See especially Clarke et al (2004), and their employment of this perspective in the British case.

See Stokes (1963) and Stokes and Dilulio (1993) on the original distinction between ‘valence’ and ‘position’ issues.

Kiewiet (1983, Chapter 2, p. 13).

A current example comes from the US 2008 presidential election study by Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, who find that voter preferences on progressive tax policy strongly influenced Obama support: Lewis-Beck and Nadeau (2009).

One may argue that pocketbook voting represents a type of positional economic voting. True, good performance from my pocketbook is certainly not a valence issue. But egotropic perceptions measure the evolution of a household economic situation compared to itself across time. As such, they do not form an indicator of a voter's place (compared to others) in the economic structure at one point in time.

Abramson et al (2003, pp. 113–115), Cautrès and Heath (1996), Evans and Norris (1997), Flanagan and Zingale (2006, pp. 115–118), Franklin et al (1992).

Historically, the French National Election Study has been fielded irregularly. However, from 1988, there has reliably been a presidential election survey. Unfortunately, the 2007 survey, although now released for general use, is of relatively little value with respect to the risk-assets economic voting hypothesis, because it has so few relevant items. For a full discussion of this problem, and its explication for the 2007 election, see Foucault et al (forthcoming). There are some asset items in French legislative surveys (1978, 1988, 2002), and these are being explored in Nadeau et al (2010).

A caveat of the present study is that assets are not measured in terms of the quantitative amount owned by households. One may conjecture that such a measure would have produced even stronger results. In addition, more detailed batteries of asset items could be imagined, which would produce even stronger effects for this kind of variable. For instance, adding a fourth item (only available for the 1988 survey) – owning shares from privatized industries – in the high-risk battery increases the coefficient when estimated on this survey. All these remarks reinforce the importance of paying more attention to the impact of assets on political preferences in future election studies.

See Kennedy (2008).

Denord (2007). See also Denord (2008).

Boy and Mayer (1993), Lewis-Beck (1993, pp. 167–186), Pierce (1995).

Boy and Mayer (1993, p. 174), Cautrès (2004).

The strategy, one of linear transformation, allows the efficient combination of a relatively large number of variables into one index. Our issue Index, I, is built from the following steps, using what amounts to a quasi-instrumental variables approach (see Kennedy, 2008, Chapter 9). Say the vote dependent variable for 1988, V88, is regressed on the seven issues, and a predicted V, call it V88-hat, created. The same is done for V95 and V02, to create predicted V variables for those years. Each of these V-hat variables are centered, by subtracting its mean, for example, V88-hat−mean V88-hat=I88. The same procedure is followed to create I95 and I02. This I score stands as a combined issue index, for assessing the impact of issues in that election year.

Reported vote is used for 1988 and 1995. Vote intention is used in 2002 to account for the Le Pen candidacy and to balance the sample sizes for the three elections (34, 34 and 32 per cent of the total sample, respectively).

It has done so in Britain, for example; see Clarke et al (2004, Table 4.3, p. 98).

It is worth recalling that the notion of total effects (that is, direct effects plus indirect effects) derives from the path analysis approach, and rests on the traditional recursive modeling assumption of one-way causality and uncorrelated errors across equations. For a current assessment of the technique, within the structural equation framework, see Kaplan (2000).

References

Abramson, P.A., Aldrich, J.H. and Rohde, D.W. (2003) Change and Continuity in the 2000 Elections. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly Press.

Alesina, A. and Rosenthal, H. (1995) Partisan Politics, Divided Government, and the Economy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Arrondel, L. (2002) Risk management and wealth accumulation behavior in France. Economics Letters 74: 187–194.

Arrondel, L., Masson, A. and Verger, D. (2004) Préférences individuelles et disparités du patrimoine. Économie et Statistiques 374–375: 129–148.

Arrondel, L. and Pardo, H.C. (2008) Les Français sont-ils prudents? Patrimoine et risque sur les revenus des ménages. Paris School of Economics, École normale supérieure. PSE Working Papers 2007–16.

Bartels, L. (2008) Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Beaudouin, J. (1990) Le ‘moment libéral’ du RPR: Essai d’interprétation. Revue française de science politique 31: 830–844.

Bélanger, É. and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (2007) French national elections: Democratic disequilibrium and the 2007 forecasts. Paper presented at the American Political Science Association meetings; September 2007, Chicago.

Benartzi, S. and Thaler, R.H. (1995) Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (1): 73–92.

Bergman, M. (2004) Examining risk attitudes. Complexity 9 (5): 25–30.

Boix, C. (2000) Partisan governments, the international economy and macroeconomic policies in OECD countries, 1964–93. World Politics 53: 38–73.

Boy, D. and Mayer, N. (eds.) (1993) The changing French voter. In: The French Voter Decides. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 167–186.

Cautrès, B. (2004) Old wine in new bottles? New wine in old bottles? Class, religion and vote in the French electorate. The 2002 elections in time perspective. In: M.S. Lewis-Beck (ed.) The French Voter: Before and After the 2002 Elections. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 74–92.

Cautrès, B. and Heath, A. (1996) Déclin du vote de classe? Une analyse comparative franco-britannique. Revue internationale de politique comparée 3: 541–568.

CEVIPOF (Centre d'études de la vie politique française). (1988, 1995 et 2002) Enquêtes électorales françaises, http://cdsp.sciences-po.fr/.

Clarke, H.D., Sanders, D., Stewart, M.C. and Whitely, P. (2004) Political Choice in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Converse, P.E. and Pierce, R.C. (1986) Political Representation in France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cordier, M., Houdré, C. and Rougerie, C. (2006) Les inégalités de patrimoine des ménages entre 1992 et 2004. In: INSEE (eds.) Données sociales. Paris: INSEE références, pp. 455–464.

Dahlback, O. (1991) Saving and risk taking. Journal of Economic Psychology 12: 479–500.

Denord, F. (2007) Néo-libéralisme, version française. Histoire d’une idéologie politique. Paris: Demopolis.

Denord, F. (2008) Et la droite française devint libérale. Le Monde diplomatique, Mars 2008.

Duch, R. and Stevenson, R. (2008) The Economic Vote: How Political and Economic Institutions Condition Election Results. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, G. and Norris, P. (eds.) (1997) Critical Election. British Parties and Voters in Long-Term Perspective. London: Sage.

Evans, J.A.J. (2004) Ideology and party identification: A normalisation of French voting anchors? In: M.S. Lewis-Beck (ed.) The French Voter: Before and after the 2002 Elections. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 47–73.

Flanagan, W.H. and Zingale, N. (2006) Political Behavior of the American Electorate, 11th edn. Washington DC: Congressional Press Quarterly.

Fleury, C.J. and Lewis-Beck, M. (1993) Anchoring the French voter: Ideology versus party. The Journal of Politics 55 (4): 1100–1109.

Foucault, M., Nadeau, R. and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (forthcoming) La persistence de l’effet patrimoine lors des élections présidentielles françaises. Revue française de science politique 61 (4).

Franklin, M.N, Mackie, T.T. and Valen, H. (1992) Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haegel, F. (1993) Partisan ties. In: D. Boy and N. Mayer (eds.) The French Voter Decides. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 131–148.

Haegel, F. and Sauger, N. (2007) L’électorat de droite: le rapport de force UMP-UDF à l’épreuve. In: P. Perrineau (ed.) Atlas électoral. Paris: Sciences Po, pp. 58–63.

Huang, C. and Litzenberger, R.H. (1988) Foundations for Financial Economics. New York: Elsevier Science Publishing Company.

Inglehart, R. (1984) The changing structure of political cleavages in western society. In: R. Dalton, S. Flanagan and P.A. Beck (eds.) Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 25–69.

Kaplan, D. (2000) Structural Equation Modeling: Foundations and Extensions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kennedy, P. (2008) A Guide to Econometrics, 6th edn. New York: Wiley and Sons.

Kiewiet, D.R. (1983) Macroeconomics and Micropolitics: The Electoral Effects of Economic Issues. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Kinder, D.R. and Kiewiet, D.R. (1981) Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science 11: 129–161.

Knight, F. (1921) Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston, MA: Hart, Schaffner and Marx.

Lancelot, A. (1981) Préface. In: C. Jacques, E. Dupoirier, G. Grunberg, E. Schweisguth and C. Ysmal (eds.) France de gauche, vote à droite. Paris: Presses de Science Po, pp. 9–14.

Lavigne, A., Mathieu, R. and de Freitast, N.E.-M. (2001) La détention d′actifs risqués selon l′âge: une étude économétrique. Revue d’Économie Politique 111 (1): 59–80.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1993) The French voter: Steadfast or changing? In: D. Boy and N. Mayer (eds.) The French Voter Decides. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 1–13.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Chlarson, K. (2002) Party, ideology, institutions and the 1995 French presidential election. British Journal of Political Science 32: 489–512.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Nadeau, R. (2009) Obama and the economy in 2008. Political Science & Politics 42: 479–483.

Lewis-Beck, M.S., Nadeau, R. and Elias, A. (2008) Economics, party and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science 52: 84–95.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Stegmaier, M. (2007) Economic models of the vote. In: R. Dalton and H.-D. Klingemann (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 518–537.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Stegmaier, M. (2008) Economic voting in transitional democracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties 18: 303–323.

Lollivier, S. and Verger, D. (1987) Les comportements en matière de d’épargne et de patrimoine. Économie et statistique 202: 65–77.

Mayer, N. and Tiberj, V. (2004) Do issues matter: Law and order in the 2002 French presidential election. In: M.S. Lewis-Beck (ed.) The French Voter: Before and After the 2002 Elections. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 33–47.

McClosky, H. and Zaller, J. (1984) The American Ethos. Public Attitudes towards Capitalism and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nadeau, R., Foucault, M. and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (2010) Patrimonial economic voting: Legislative elections in France. West European Politics 33: 1261–1277.

Nannestad, P. and Paldam, M. (1994) The VP function: A survey of the literature on vote and popularity functions after 25 years. Public Choice 79: 213–245.

Norpoth, H. (1996) The economy. In: L. LeDuc, R.G. Niemi and P. Norris (eds.) Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 299–318.

Pierce, R.C. (1995) Choosing the Chief: Presidential Elections in France and in the United States. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Piketty, T. (2003) Income inequality in France, 1991–1998. Journal of Political Economy 111: 1004–1042.

Piketty, T. and Saez, E. (2003) Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 1–39.

Rougerie, C. (2002) Évolution des inégalités de patrimoine entre 1986 et 2000. Données sociales, Insee.

Sauger, N. (2009) Agenda électoral et vote sur enjeux. In: B. Cautrès and A. Muxel (eds.) Comment les électeurs font-ils leur choix? Le Panel électoral français 2007. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, pp. 181–200.

Stokes, D.E. (1963) Spatial models of party competition. American Political Science Review 57: 368–377.

Stokes, D.E. and Dilulio, J.J. (1993) The setting: Valence politics in modern elections. In: M. Nelson (ed.) The Elections of 1992. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly Press.

Stonecash, J.M. (2000) Class and Party in American Politics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

To, T. (1999) Risk and evolution. Economic Theory 13 (2): 329–343.

Whitten, G. (2004) Could there have possibly been economic voting? In: M.S. Lewis-Beck (ed.) The French Voter Before and After the 2002 Elections. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 126–135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Sources

Data come from three national surveys performed under the supervision of the CEVIPOF (Centre d’études de la vie politique française) in 1988, 1995 and 2002 (see Cautrès, 2004). Data are available at the following website: http://cdsp.sciences-po.fr/.

Variables

Presidential vote=1, if respondent supports a right-wing candidate in the presidential election, 0 otherwise (vote reported for 1988 and 1995, vote intention in 2002 because of the Le Pen candidacy).

Party identification=1, if respondent identifies with a right-wing party, 0 otherwise.

Ideology=1 if respondent locates on points 5, 6 or 7 on a left-right scale, 0 otherwise.

State regulation=1, if respondent thinks that the State should not regulate private firms more tightly in times of economic difficulties, 0 otherwise.

Socialism, nationalizations, stock market, profits, privatizations=1, if respondent expresses negative views about the first two terms and positive views about the last three, 0 otherwise.

Savings account=1, if respondent owns a saving account, 0 otherwise.

House/apartment=1, if respondent owns his or her house/apartment, 0 otherwise.

Country House=1, if respondent owns a country house, 0 otherwise.

A business, farm, or piece of land=1, if respondent owns a business, a farm or a piece of land, 0 otherwise.

Rental properties=1, if respondent owns a rental property, 0 otherwise.

Stocks=1, if respondent owns stocks, 0 otherwise.

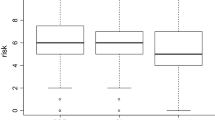

Low-risk scale=Average of Saving accounts, House/apartment and Country House.

High-risk scale=Average of Business, farm or piece of land, Rental properties and Stocks.

Age=Age rescaled from 0 to 1.

Gender=1, if male, 0 if female.

Education=Level of education attained, rescaled from 0 to 1.

Income=Household total income, rescaled from 0 to 1.

Professionals=1, if senior manager or professional, 0 otherwise.

White collars=1, if white collar, 0 otherwise.

Blue collars=1, if blue collar, 0 otherwise.

Private sector=1, if working in the private sector, 0 otherwise.

Religion=1, if Catholic and attending church at least once a month, 0.67 if Catholic and attending church less than once a month, 0.33 if other religions, 0 otherwise.

Immigration=1, if the respondents strongly agree ‘there are too many immigrants in France’, 0.67 if somewhat agree, 0.33 if somewhat disagree, 0 if strongly disagree.

Economics=1, if ‘no risk of unemployment’ in 1988, ‘economy better’ in 1995, ‘unemployment not a priority’ in 2002; 0.5 if ‘small risk of unemployment’ in 1988, ‘economy same’ in 1995, ‘unemployment not a second or third priority’ in 2002; 0 if ‘high risk of unemployment’ in 1988, ‘economy worse’ in 1995, ‘unemployment first priority’ in 2002.

Homosexuality=1, if respondents ‘strongly agree’ that homosexuality is morally condemnable, 0.67 if somewhat agree, 0.5 if no opinion, 33 if somewhat disagree, 0 if strongly disagree in 1988; 1 if ‘strongly disagree’ homosexuality is an acceptable way of living one's sexuality, 0.67 if somewhat disagree, 0.5 if no opinion, 0.33 if somewhat agree, 0 if strongly agree, in 1995 and 2002.

French identity=1, if respondents ‘strongly agree’ they are proud of being French, 0.67 if somewhat agree, 0.5 if no opinion, 33 if somewhat disagree, 0 if strongly disagree, in 1988; 1 if respondents feel French only, 0.5 if they feel more French than European, 0 otherwise in 1995 and 2002.

Death penalty=1, if respondents ‘strongly agree’ death penalty should be reinstated, 0.67 if somewhat agree, 5 if no opinion, 33 if somewhat disagree, 0 if strongly disagree.

Environment=1, if respondents are willing to support an association for the defense of environment, 0 otherwise in 1988; 1 if environment is graded 8, 9 or 10/10 on a scale of problem importance in 1995, 0 otherwise; 1 if environment is identified as the most or second most important problem in 2002, 0 otherwise.

School=1, if respondents find ‘very serious’ the abolition of the free choice between public and private school, 0.67 if somewhat serious, 0.5 if no opinion, 33 if not very serious, 0 if not serious at all in 1988; 1 if respondents perceive private school as ‘very positive’, 0.67 if somewhat positive, 0.5 if no response, 33 if somewhat negative, 0 if very negative in 1995 and 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nadeau, R., Foucault, M. & Lewis-Beck, M. Assets and risk: A neglected dimension of economic voting. Fr Polit 9, 97–119 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2011.5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2011.5