Abstract

The importance of relationships between buyer and sellers in marketing research is well established. This study contributes to relationship marketing (RM) research as it examines the microfoundations of financial service buyer and seller relationships. The study uses intersubjective theory and a qualitative method with the purpose of conceptualising the qualitatively different ways customers experience face-to-face interactions with a service provider. An empirical study is conducted to determine, based on the customer's own words, what is experienced in the interaction between the customer and the provider. Findings from the empirical material show that not all personal interactions between customers and a service provider, in this case a bank, can be labelled as relationships. Instead, what customers do perceive as a relationship is an encounter where the interaction entails symmetry in the way the customer and the provider mirror each other. When customers receive a treatment in opposition to an expectation of intersubjectivity, they will not refer to the situation as a relationship and, subsequently, according to the underlying assumptions of RM, do not willingly engage in further business with the provider.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Relationships between buyers and sellers have been found important to understand markets from both the perspective of economics1, 2 and relationship marketing (RM).3, 4, 5, 6 To date, much research has been produced on the relationship between commitment and benefit in relationships.7 The amount of time and resources that firms and consumers are willing to spend on developing their interactions often relates to the benefit they perceive that they stand to gain from their efforts.8 Customers’ and providers’ understanding of the relationship context often requires commitments in terms of time and resources that neither selling firms nor consumers are willing or able to invest.2 Relationships are multifarious in real life, as evidenced by the multitude of definitions for the term relationship in research. Two frequently mentioned dimensions of relationships are the more physical coordination of activities9 and the more cognitive trust, commitment and understanding of the relationship.10 RM is frequently defined as follows: ‘to attract, retain and enhance new customer relations’.3 None of these definitions explicitly incorporates the relationship context.

The context of a relationship is frequently considered what is ‘outside’ of the relationship, such as demographics,11 service industry12 and international setting.13 However, this study brings forward what is ‘inside’ the relationship as a microcontext of the relationship. The microcontext refers to the relational recognition of parties involved in the exchange. To the best of our knowledge, little or no consideration of the microcontext of the relationship has occurred in RM research. This shortcoming has been emphasised by Barnes,14 who finds that relationships may differ in kind, depending on the depth of involvement. Customers may, for instance, be locked in by erecting barriers to exit through high switching costs.15 Other customers may be subjected to elaborate database marketing efforts, which equate forming relationships with collecting pertinent information about customers, usually relating to their demographic and psychographic characteristics16 and their buying behaviour,17 and then using this information to direct appropriate targeted messages to them. In this respect, retention achieves a relatively limited motivation for the customer to engage actively in the development of the relationship.14

The main purpose of this article is to conceptualise the qualitatively different ways customers experience face-to-face interactions with a bank, as a potential means of contributing to theory building. Using a framework of intersubjectivity, an empirical study was conducted to determine, based on the customer's own words, what is experienced in the interaction between the customer and the bank. With a grounded theory approach18 we then constructed categories based on the customer's own use of metaphors, to enhance the understanding of how customers talk about their interactions with the provider, followed by a discussion of the implications for theory and practice. The methodology thus provides an alternative and a complement to methods that first derive theoretically motivated ideal types and then study the empirical material.19

This study contributes by studying the applicability and usefulness of RM to financial services research, and it contributes to RM research in three main ways. First, it contributes towards an increased understanding of the microfoundations of RM by focusing on the intersubjective aspect of relationships. Second, it answers calls for further studies into the applicability of RM in commercial mass-market settings.20 Third, it answers calls for increased knowledge regarding the applicability of RM in a heterogeneous market because the empirical application is in the financial services industry.21

This study also sheds new light on the financial crisis of 2008–2010 as it contributes to a better understanding of the context in which individuals took on too large housing loans. Following the crisis, there is a trend towards increased regulation, and this study also points to the fact that such regulation needs to consider the nature of the interaction between sellers and buyers of financial services.

TOWARDS AN INTERSUBJECTIVE UNDERSTANDING OF A RELATIONSHIP

What is usually characterised as a relationship in RM is often artificially maintained through the use of incentives such as customer clubs and frequency marketing programmes.14 On the basis of a survey of 400 retail bank customers, Barnes22 concludes that it is not ‘inconceivable that customers may be retained, often for very long periods, without a genuine relationship being presented’ (p. 767).22 Thereby, he distinguishes genuine customer relationships from artificial ones, where he sees a serious lack of the genuine ones in the practical outcome of RM.23 Customer retention does not provide evidence of the existence of a ‘relationship’ because a customer may have a variety of reasons for returning to the same service provider.

Others have used the concept of distance as a way of better understanding the relational aspects of the service encounter.24, 25 This article is concerned with how customer and supplier perceptions mirror each other in a relationship, which is why the idea of distance is not in focus in this article.

Relationship development can be achieved when there is reciprocal value addition and idiosyncratic commitments8 in a sincere dialogue and when the customer perceives that a mutual way of thinking exists between the two parties.26, 27 Grönroos describes the context of the relationship between a firm and a customer as follows:

In an on-going relationship context it is not only the firm, which is supposed to talk to the customer, and the customer who is supposed to listen. It is a two-way street, where both parties should communicate with each other. In the best case a dialogue develops. (p. 5)23

Fundamental to such development processes is that the providers enable the customers to perceive the providers as resources that can benefit the customers if the customers commit their own resources, and vice versa. It is thus vital to the relationship development process that both the provider and the customer mirror each other in a continuous generative movement. When discussing the development of relationships, it is essential to conceptualise the differences in how customers experience an encounter in a business setting, which is what this study aims to do. Critics of the relationship concept in RM, regarding the lack of concern for whether the customers are willing participants in a relationship or not, point out a need for research where the relational aspect of RM is focused.22, 19, 28, 29

Consequently, there is a need to distinguish between a punctual and a relational perspective.30, 31, 32 The punctual perspective has its roots in the Platonic/Cartesian tradition of studying isolated entities and cause and effect and thus regards consciousness as something individual that receives knowledge in a passive manner. The relational perspective is, in a Hegelian tradition, a dialogical–dialectical approach that emphasises the reciprocal relationship between, for example, thought and the act of thinking, and in which knowledge is received through a circular process, where the criteria are internal. Hereby, we call for a shift from seeing relationships as linear and punctual (for example, the very frequently used five-phased model where initiation, growth, maintenance, deterioration and dissolution are seen as stages in a chain of activities33) to a perspective that is set out from a relational and intersubjective perspective.

Buber, probably most known for his philosophy of dialogue, uses the term the space between as a reference to what we see as the intersubjective nature of relationships: that self and other are not separable.34, 35 Follett, who views interaction as the site for connection where the self is affected and changed,36 uses the term circular response, as opposed to the Western assumption of linearity (also comparable with the underlying assumptions of linearity within RM):

Through the circular response, we are creating each other all the time. I never react to you but to you-plus-me; or to be more accurate, it is I-plus-you reacting to you-plus-me. “I” can never influence “You” because you have already influenced me; that is in the very process of meeting, we both become something different. (pp. 41–42)37

The nexus of the thoughts of Follett is thus on relationality, as she states that ‘reaction is always reaction to a relating’ (p. 62),36 meaning that the reality does not consist of isolated and measurable entities but of the relationship between subjects and objects in an interaction. One intriguing consequence of this view is that goals and interests are seen as unstable; they are not created in isolation but in a context of interdependent negotiation where we constantly create each other. This implies a need for shifting focus from the assumptions of self-interested and static individuals coming together to the relational dynamics and interactional practices that encourage a new understanding of a relationship. We cannot talk about ‘result of process’ because there is only ‘moment in process’ (p. 60).36 Von Wright30 concludes that ‘the uniqueness of a person is found within the inter-subjective in-between space, the encounter’ (p. 224).30

This brings us to the concept of intersubjectivity as a way of describing what goes on between people. Instead of leaning towards the tradition of interpreting intersubjectivity as joint knowledge among a group of people, as supported by Husserl's38 use of the word, we base our understanding of interaction and the becoming of the self on the pragmatic views of Mead.39 Intersubjectivity is understood here as the process of constant becoming of the self in interaction with others.

Mead, who does not himself use the word intersubjectivity, establishes the concepts of I and Me to describe this continuous and circular process of becoming human by reflecting upon the ‘new’ self-created in every encounter with someone outside one's own body. In the act of becoming through interaction with others, the intersubjectivity can be described as the source necessary for the notion of subjectivity to appear for each individual. Through the Me's interaction with others, we see ourselves, making self-reflection possible; the I is re-established as something else than before and therefore new.39

Von Wright30 emphasises the importance of action and, with the help of Joas40 and the action philosophy of Arendt,41 she names Mead's intersubjectivity a practical one. What goes on between people – in actions in the space between – constitutes our becoming and gives meaning to the relational perspective used in this study. Von Wright30 establishes the two concepts of What and Whom. To see someone as a What is to focus on labels such as: woman, man, young, poor, native or dentist and so on. The Whom way of engaging in an intersubjective action is to adopt the other's perspective by asking for things that make this person a concrete other.

In this study, this terminology of What/Whom is used as the means for interpreting what is expressed by the customers in the context of a business meeting with reference to the space between the customer and the provider. The current state of knowledge does not make it possible to anticipate the results of such an interpretation of the space between. Rather, we need to explore these issues and ask the following questions: How do the customers conceptualise the interaction and the remaking of the other? How can we make sense of the different stories told by the customers? The customer's preferential right to interpret the relationship has been put forth in previous studies on RM42, 43 and is also advocated here. It is the customer and not the company that defines if there is a relationship or not.

THE EMPIRICAL MATERIAL AND METHOD OF ANALYSIS

This study is based upon a careful process of gathering and analysing empirical data with a qualitative approach grounding the derived concepts stepwise in the empirical data. The empirical material used in the analysis is the customers’ own stories. Seventeen bank customers were interviewed for as long as it took them to tell their stories (between 2 and 3 hours). The interviewing team included psychologist Graham Barnes, PhD, whom we hereby acknowledge. Every interview was videotaped,44 which on the one hand made it possible to show the interviews to the customers and on the other also made the material continuously available for the authors in a rigorous process of abduction. The interviews focused on scheduled interactions with an advisor (that is, the person-to-person encounter) and not upon other possible mediated interactions with the bank, such as via the telephone or the Internet. The 17 customers interviewed were purposely selected by the researchers out of a theoretical interest in maximising differences in the ways in which customers think of their contact with a bank advisor.

After each interview, that took place in a room arranged for the purpose outside the bank branch, the steps in the analysing process were the following:

-

1

Each videotape was analysed immediately after the interview together with the specific customer, to gain knowledge of the customer's understanding of her or his financial self and way of relating to the bank advisor and to the bank. This made it possible for the researchers to ask questions about things said in the interview and thereby better understand the perceptions of each customer. This step was documented by one of the researchers taking notes. These notes were then used as material for analysis together with the videotapes.

-

2

The story of each of the customers (on videotape, transcripts of the videotaped interview and as field notes as described above) was then analysed by each author separately and then discussed between the authors in a systematic attempt to derive concepts and try to understand what the stories entailed for the respective customer. Concepts from different interviewees were gathered together and again checked against the field material to reach saturation18, and categories were created by the authors. These categories were then tested against each one of the 17 stories to look for similarities and differences in the material. It is important to emphasise that the categories are derived from the material to show patterns of experiences among the customers. Because all of the 17 interviewed customers had seen the videotape with their own performance and also analysed the content together with the team, we had a large pool of material to use for the derivation of patterns.

-

3

The customers’ different accounts were reconstructed into four qualitatively different conceptions of how customers feel they were constituted during their meeting with a bank advisor. In an ideal-typical way, these four stories reveal when customers perceive the existence of a relationship with a provider and when they do not. Metaphors45, 46, 47 used by one or more of the customers have been used as a means of emphasising the points of special interest we want to make in summarising how the customers make sense of their interaction with the bank – the relational aspect.

THE CUSTOMERS’ WAYS OF MAKING SENSE OF THEIR PERSONAL CONTACT WITH THE BANK

When the customers’ interview responses were analysed for the existence of patterns, four categories, or metaphorical stories, emerged. The four types of customers’ stories, from which four categories of customers’ perceptions of their experiences with their banks were created, should not be interpreted as the essence, or an attempt to approximate the essence, of the individual qualities of the experiences in the space between. Instead, these stories simply represent four qualitatively different ways the customers experienced their interaction with their bank. The categories were created to help interpret the customers’ descriptions of their business meetings with the provider and connect to theory.

‘It is like going to the dentist’ (What–What). Here one of the metaphors used by customers was the resemblance with the relation to a dentist or a physician. The story tells about two persons interacting independently and seeing each other as objects or functions: customer/bank advisor. The interaction is described by the customers as professional from both parts. The ‘It is like going to the dentist’ story is as follows:

I know a lot about my own finances and have adequate knowledge about what I want from the bank. I am always well prepared and have questions I want to ask my bank contact. I am not interested in any kind of personal relationship with the bank and really dislike when they ask about my private life. I do not mind changing bank advisor[s] as long as he or she has the equivalent competence. The bank and their advisors are there to provide me with functions to make my private and professional life easier, and I assume they do this in a proper and professional way. I trust the system to serve me well.

The ‘It is like going to the dentist’ represents a professional customer relationship with the bank; in this situation, customers feel they are respected and seen as customers by professional bank advisors who know their job. The customer stories that fall under the category of the ‘It is like going to the dentist’ describe how customers have no interest in being treated as a Whom but prefer to have a non-familiar relationship with a professional person (a What-relationship). For example, one customer said:

I would like to get proper and skilled assistance with my financial transactions. Mostly, I already know when I come to the bank exactly what and how I want it done.

Customers whose descriptions fall under the category the ‘It is like going to the dentist’ are typically forthright about expressing ideas and opinions of how to improve retail banking and feel assured in themselves as financial beings. For example, one customer opined:

I often feel I know more about finance than do[es] the bank advisor. Sometimes I also know more about how the bank is operating. I think this shows that the bank needs to operate more like one system.

Another customer who was not shy about expressing an opinion said:

I told the advisor to change bank[s]. He was good at it and should not work where he is not appreciated.

Other characteristics of these customers include an interest in their own economy, a propensity for doing home budgets and an inclination to search for information to learn more.

On the basis of the customer responses that fall under the ‘It is like going to the dentist’ category, these customers express neither trust for the individual nor the brand; however, they do trust the banking system as a whole. The bank is seen in a larger context as a part of the overall economy and as a link to participating in societal life.

‘It is like I am unseen’ (Whom–What). Here frustration is expressed as the customer expects a personal relationship whereas the advisor offers a professional one:

I am aware of that I would gain from having a good relationship with the bank and I keep trying to present myself in a way that they would appreciate. But, no matter how I do it, they are not responding. They do not meet me as a person but see me as a label, if feel met like something minor and unimportant to their business. I do not find a relationship even if I keep trying. I have told them I have plenty of money and a stable job and good references, but they are still not interested; they even look a bit scared when we meet and keep talking instead of listening to me.

This category describes how customers try to establish personal contact with the bank but receive no or very little response to their attempts. The ‘It is like I am unseen’ – category includes stories of deeply unsatisfied customers who define their relationship with the bank as non-existent. They want to be engaged in a relationship with the bank but describe situations where their attempts are rejected. This category consists of those customers’ descriptions that indicated the customers’ desire to be seen as Whom. Consequently, numerous attempts to present themselves as such were described in these stories. Simultaneously, they perceived that the bank has rejected these attempts. ‘It is like I am unseen’ present themselves as Whom but are treated as What, which makes any type of relationship impossible. One customer who met with a banking advisor stated that:

He never looked me in the eye, never asked anything about me, but then tried to tell how customers like me should arrange their finances. I just could not listen since it wasn’t me he was talking to.

‘It is just prying’ (What – Whom). The customer expects a professional relationship with the advisor, but is met with intimate questions about private life and family affairs.

She tried to pry into my private sphere asking about my leisure-time activities and where I had been during the holidays. But I told her very distinctly I was not interested in that kind of relationship. She should stick to being professional and do what I ask her to do.

This felt intrusion into the private sphere makes these customers avoid the bank. They feel intimidated and find other ways of getting the financial advice they need. They then use the bank only for transactions.

I use my bank for small withdrawals, to check my account or to have a safe-deposit box. But when it comes to my savings and loans, it is my husband who takes care of it and the relationship is between him and his bank. I just sign the papers. I just hate those ambitious bank people who try to be friendly with me. I do not understand why they keep asking about my private affairs, and I do not want to talk to them. They seem to be wanting some kind of closeness that I am not at all interested in.

These types of customers tend to distrust banks and other institutions in society and prefer to rely on a known relationship with someone close for getting financial advice. The ‘It is just prying’ – customer really dislikes when a bank attempts to establish a relationship and actively tries to keep the bank at a distance. As evidenced by the customer descriptions, these customers generally have a distrust of banks. For example, one customer admitted that:

I do not trust them. And I do trust my father, so why change a good arrangement?

Another customer stated that:

I feel they are trying to sell me things I do not need and explain it in a way I do not understand.

As evident from their customer descriptions, ‘It is just prying’ – customers do not refer to their encounters with bank advisors as relationships. Instead, other perceived relationships play a more prominent role when it comes to handling or discussing financial matters. The bank is perceived as actively trying to ‘attack’ customers.

‘Like someone I really know’ (Whom–Whom). This entails two persons engaged in a somewhat intimate interaction. They both see each other as Whom and both share stories from their private spheres. The ‘Like someone I really know’ – story is as follows:

I like to go to the bank because of my relationship with teller X. She/he understands my economy and me and is sincerely interested in learning more about me. I feel this personal relationship is important to me; I trust him/her and would gladly follow if she/he changed employers. I often leave the branch office having done business with the bank that I had not planned when I went there. I believe that my teller X gives me good advice and that I need not check with anyone else or learn more than I want to. I am really not that interested in finance.

The story of ‘Like someone I really know’ indicates that customers are willing to engage in a relationship with one specific person at the bank with whom they entrust their personal finances. Customers and providers who are included in this category have a very close relationship and often talk about personal things outside the financial sphere. For example, one customer described her bank advisor as follows:

She knows me and my family and always ask[s] about my children. I like it and appreciate that her advice always [is] adapted to my circumstances. It is the right thing for me, and I just have to accept her proposals.

When another customer was asked to describe her bank advisor, she said:

He is interested and I feel he really likes me. So I like him and therefore trust him.

This comment illustrates how establishing a relationship with a specific bank advisor can instil a feeling of trust within the customer. In turn, this feeling of trust can create a sense of loyalty to a bank advisor, as evidenced by the following customer comment:

He helped me out once when I was in trouble, having bought a house we could not afford. Since then I trust him and would never like to change him for anyone else. I have actually once changed bank[s] to follow him in his career. I feel completely confident in his advice.

These customers like to receive advice and trust the bank, the teller and the overall banking system to help in the best possible way. On the basis of the customer descriptions, customers and bank advisors who belong to the ‘Like someone I really know’ – category see each other as Whom.

SUMMARY OF CUSTOMER STORIES

Mutual relationships between customers and providers appear to exist in only two of the four categories, the ‘It is like going to the dentist’ and the ‘Like someone I really know’. In these two categories of customer stories, we find the kind of intersubjectivity in which customers and service providers can establish genuine relationships. As a consequence, customers belonging to these two categories regard their banking encounters as being filled with respect for their person and individual nature. The customer interviews revealed that customers comprising these two categories were receptive to conducting business because they felt they were on equal terms with their bank. In these two situations, the bank and the customer both viewed each other as What (‘It is like going to the dentist’) or as Whom (‘Like someone I really know’).

Two other categories also emerged from the material – ‘It is like I am unseen’ and ‘It is just prying’. Customer stories from these two categories did not reveal the existence of mutual relationships between customers and providers. In fact, these customers did not believe that they had any type of relationship with their bank; therefore, we can think of it as an artificial one using the definition set forth by Barnes.22 Customers who are characterised as ‘It is like I am unseen’ desperately want attention from their bank but fail to receive it, whereas customers who are characterised as ‘It is just prying’ actively want to avoid any type of personal relationship with their bank, as they had experiences of intimidating attempts from advisors in the past.

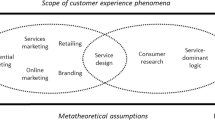

When customers from these two categories interact with service providers, relational conflicts occur. Therefore, these customers do not regard these types of interactions as a form of relationship (Figure 1).

This finding suggests that customers’ appreciation of a relationship is dependent on the intersubjectivity that occurs during the meeting between the two parties. For the concept of relationship to be used as a definition by customers, symmetry must exist. If the opposite (that is, asymmetry) occurs, customers themselves do not define this type of interaction as a relationship. An intersubjective mirroring of the other must occur for the customer to perceive there is a relationship.

AN INTERSUBJECTIVE UNDERSTANDING OF A RELATIONSHIP AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR RM THEORY

The purpose of this study was to focus on the intersubjective microcontext as a possible means of contributing to RM theory building. On the basis of a qualitative analysis of empirical material, we determined that the customers’ stories about their face-to-face interactions with service providers could be interpreted and categorised in four qualitatively different ways. These interpretations indicate the importance of looking for symmetrical variations when studying the microcontext of a relationship.

Others have, as mentioned earlier, put forth the concept of distance as a way of understanding what goes on in a business relationship.24, 25 The idea of closeness and distance, although interesting, is not applicable in this study. The results show evidence that the customers do not perceive all close interactions with the bank advisors as relationships, and that they perceive distance as sometimes something desirable and sometimes not. The concepts of distance and mirroring in relationships seem to be very different dimensions that cannot easily be combined, or compared.

What we refer to as the What–What and the Whom–Whom ways of mirroring each other are what a customer perceives and labels as a relationship. When the encounter can be described using the asymmetrical What–Whom or Whom–What, no relationship exists according to Grönroos’ definition of a relationship23 through sincere dialogue, because at least one party fails to perceive it. The concepts of Whom and What – of relational or punctual – consequently give us the tools to look at relationships in a new way. By investigating the microcontext of a single business meeting and how the customer interprets it, we hope that it can be used as a starting point of a more specific focus in RM research. On the basis of our results, customers want to be in contact with providers (through what they call a relationship) in one of two different ways that we categorised as: ‘It is like going to the dentist’ or ‘Like someone I really know’. We also interpreted customers’ descriptions of their lack of a relationship with providers in two different ways, which we then categorised as ‘It is like I am unseen’ and ‘It is just prying’. The findings of this study give us reason to call for further inquiries into what customers perceive as a sincere dialogue and what they do not.

An analysis of the empirical material gives us reason to believe that we can develop the theory of RM by adding an internal focus, thereby emphasising the internal context of relationships and the fact that not all business encounters are labelled as relationships in the eyes of the customers. This study also gives us the means of constructing a possible answer to the question of why customers may not sense the existence of a relationship when interacting with the provider.

The categorisation of a Whom–Whom relationship, metaphorically named ‘Like someone I really know’ here, corresponds to the high-volume, close, dynamic relationship that textbooks in RM often describe as the ultimate and desirable mode of doing business. Our findings also showed that a What–What relationship, which is often considered a transaction because it is conducted at arm's length, possesses the same characteristics (satisfaction, long duration and loyalty) that commonly define relationships. Contrary to perceived RM theory, a fictitious customer who belongs to the category described by the What–What relationship is fully satisfied and not in search of what we interpreted as a Whom–Whom relationship.

The implications for RM theory are twofold. First, the developmental aspects of relationships need to be reconsidered. We call for the removal of the term enhance from Berry's definition of RM, ‘to attract, retain and enhance new customer relations’.48 Second, the definition of relationship needs to be reconsidered because the ‘It is like going to the dentist’ – category, which represents a What–What relationship, does display common properties of a relationship, such as satisfaction, long duration and loyalty, but without a willingness to further develop intimacy with the service provider as a person. As a consequence, we can conclude that it is of great strategic importance to listen to how customers talk about their interactions with a provider to mitigate customer switching.

In the act of becoming a customer, the provider is needed as a mirror of the self for the counterpart and vice versa. If we drop the punctual and linear assumptions of the individual and shift towards relationality and the concept of mirroring and creating each other in the business meeting, we can also become receptive to new explanations of why RM fails to materialise. The customer and the provider cannot be regarded as two isolated entities when talking about relationships in RM. What we have to investigate further is the generative processes of mirroring each other. We have to understand the ‘and’ in ‘customer and provider’. We believe the way that the provider mirrors the customer plays a decisive role in the customer's willingness to become a customer in this context. The willingness to be a customer is deciding whether the customer will engage in any business transactions with the provider. Our intention here is to put forward a need for understanding intersubjectivity from a ‘becoming of the self-perspective’.

When providers fail to mirror their customers, business meetings or interactions between these two parties will deteriorate, possibly impeding a business contract or, at the very least, future business contracts. This failure of providers to mirror their customers is of great importance because an underlying assumption of RM is that it is better business to retain old customers and conduct more business with them than to establish new business relationships. However, if the old customers are reluctant ones, as interpreted by the categorisation of the ‘It is just prying’ the retaining costs might be too high. The categorical description of the ‘It is like I am unseen’ shows how customers try to connect and become involved in conducting business with a provider, who in turn does not respond. The provider's neglect of the customer is an example of badly treated customer relations.

This study suggests that intersubjective symmetry should be considered an important factor in RM theory. This of course raises some interesting questions for practitioners in the field because these findings also have implications for segmentation: How does one know when the customer wants to be treated as a Whom or as a What? Accordingly, any segmentation of customers should build on an intersubjective understanding of the relationship to craft the relevant distribution strategies.

FUTURE RESEARCH

An important theoretical follow-up of this article is a study of the actual interaction, the business meeting, between the advisors and their customers or to determine what goes on in the space between them. By applying the concepts drawn upon in the present study, we may then try their relevance as a means to describe the actual relationship and in this way confirm or reject the attempt of claiming a more general theoretical contribution made in this study. Such a research design may benefit from considering the findings of Beckett et al,19 which purchasing behaviour depends on the type of financial service purchased, and that delivery channels are important for the purchase behaviour. The interaction may also depend on the factors found by Beckett et al.19

Two future research areas are obvious:

-

1

The definition of a business relationship should be reconsidered in terms of intersubjectivity.

-

2

Instead of trying to develop relationships through a segmentation approach, RM should focus on finding the appropriate level of involvement for each customer (What–What or Whom–Whom).

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY

The findings of this study suggest that financial services firms should implement marketing practice to achieve a balance between the customer's and the advisor. The customer may be perfectly happy about having a low or a high-involvement relationship with the bank, and the bank organisation should probably be more sensitive to the wishes of the customers. Presently, many banks spend much money and work effort trying to push their customers into a high-involvement mode, and this study suggests that this may be contrary to what the customer wants.

The current regulatory initiatives in Europe and the United States point to the importance of consumer protection. This study highlights that there is a danger of mismatch between buyer and seller when the intersubjective mirroring is imbalanced. In practice, a mismatch may result in poor, or even wrong or illegal advice from the seller of financial services.

This study also suggests that the high-involvement balance relationship, the Whom–Whom relationship, is a state of relationship exchange where customers and bank sellers effectively learn from each other in a respectful way. In this kind of exchange, the financial service seller does much effectively to increase financial literacy. The framework of this study could thus be a tool to single out the kinds of relationships that could be targeted by authorities responsible for financial literacy. These authorities could then also devise other educational efforts that are suited for imbalanced or low-involvement relationships.

References

Stiglitz, J.P. (1998) Distinguished lecture on economics in government: The private uses of public interests: Incentives and institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (2): 3–22.

Kranton, R.E. (1996) Reciprocal exchange: A self-sustaining system. American Economic Review 86 (4): 830–851.

Berry, L. (1983) Relationship marketing. In: L.L. Berry, L. Shostack and G. Upah (eds.) Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, pp. 25–28.

Ford, D. (1997) Understanding Business Markets: Interaction, Relationships and Networks. London: Dryden.

Grönroos, C. (1996) Relationship marketing: Strategic and tactical implications. Management Decision 34 (3): 5–14.

Sheth, J.N. and Parvatiyar, A. (1995) The evolution of relationship marketing. International Business Review 4 (4): 397–418.

Gundlach, G.T., Achrol, R.S. and Mentzer, J.T. (1995) The structure of commitment in exchange. Journal of Marketing 59 (January): 78–92.

Anderson, E and Weitz, B. (1992) The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research 29 (1): 18–34.

Håkansson, H. (1982) International Marketing and Purchasing of Industrial Goods: An Interaction Approach. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Alter, C. and Hage, J. (1993) Organizations Working Together. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Carrigan, M. (1999) ‘Old spice’ – Developing successful relationships with the grey market. Long-Range Planning 32 (2): 253–262.

Pressey, A. and Mathews, B.P. (2000) Barriers to relationship marketing in consumer retailing. Journal of Services Marketing 14 (3): 272–286.

Odekerken-Schröder, G., De Wulf, K. and Reynolds, K.E. (2005) A cross-cultural investigation of relationship marketing effectiveness in retail services: A contingency approach. Advances in International Marketing 15: 33–73.

Barnes, J.G. (1994) Close to the customer: But is it really a relationship? Journal of Marketing Management 10 (7): 561–570.

Roos, I. (1999a) Switching processes in customer relationships. Journal of Service Research 2 (1): 68–85.

Frank, R.Y., Massy, W.H. and Wind, Y (1972) Market Segmentation. NJ, USA: Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Ezell, H.F. and Russell, G.D. (1985) Single and multiple person household shoppers: A focus on grocery shopping criteria, and grocery shopping attitudes and behaviour. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 13 (1): 171–187.

Glaser, B.G and Strauss, A. (1967) Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

Beckett, A., Hewer, P. and Howcroft, B. (2000) An exposition of consumer behaviour in the financial services industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing 18 (1): 15–26.

O'Malley, L. and Tynan, C. (2000) Relationship marketing in consumer markets: Rhetoric or reality. European Journal of Marketing 34 (7): 787–815.

Carson, D., Gilmore, A. and Walsh, S. (2004) Balancing transaction and relationship marketing in retail banking. Journal of Marketing Management 20 (3–4): 431–455.

Barnes, J.G. (1997) Closeness, strength, and satisfaction: Examining the nature of relationships between providers of financial services and their retail customers. Psychology & Marketing 14 (8): 765–790.

O'Malley, L. and Prothero, A. (2004) Beyond the frills of relationship marketing. Journal of Business Research 11 (57): 1286–1294.

Wuyts, S., Colombo, M.G., Dutta, S. and Nooteboom, B. (2005) Empirical tests of optimal cognitive distance. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization 58: 277–302.

Leonidou, L.C., Barnes, B.R. and Talias, M.A. (2006) Exporter-importer relationship quality: The inhibiting role of uncertainty, distance and conflict. Industrial Marketing Management 35: 576–588.

Grönroos, C. (2000a) Creating a relationship dialogue: Communication, interaction and value. The Marketing Review 1: 5–14.

Grönroos, C. (2000b) Service Management and Marketing – A Customer Relationship Management Approach. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Barnes, J.G. and Howlett, D.M. (1998) Predictors of equity in relationships between financial services providers and retail customers. International Journal of Bank Marketing 16 (1): 15–23.

Czepiel, J.A. (1990) Service encounters and service relationships: Implications for research. Journal of Business Research 20: 13–21.

Wright von, M. (2000) Vad eller vem? – En pedagogisk rekonstruktion av G H Meads teori om människors intersubjektivitet. Uddevalla, Sweden: Daidalos.

Farr, R.M. (1996) The Roots of Modern Social Psychology 1872–1954. Oxford/Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Marková, I. (1982) Paradigms, Thought and Language. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

Levinger, G. (1983) Development and change. In: H.H. Kelley et al (eds.) Close Relationships. New York: W.H. Freeman, pp. 315–359.

Buber, M. (1970) I and Thou. New York: Scribner's Sons.

Buber, M. (1984) Das dialogische Prinzip. Heidelberg, Germany: Schneider.

Follett, M.P. (1924) The Creative Experience. New York: Longmans, Green.

Follett, M.P. (1924/1995) Relating: The circular response. In: P. Graham (ed.) Mary Parker Follett: Prophet of Management. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, pp. 35–65.

Husserl, E. (1907/1964) Ideas of Phenomenology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Mead, G.H. (1934) Mind, Self and Society. From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviourist. Chicago, II. USA University of Chicago.

Joas, H. (1997) G.H. Mead. A Contemporary Re-examination of His Thought. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Arendt, H. (1958) Human Condition, 2nd edn. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Grönroos, C. (2002) Service Management och marknadsföring: en CRM ansats. Malmö, Sweden: Liber ekonomi.

Roos, I. (1999b) Switching paths in customer relationships. Doctoral thesis no 78, Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration, Helsinki.

Aspers, P., Fuehrer, P. and Sverrisson, Á. (2004) Bild och samhälle: Visuell analys som vetenskaplig metod. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Cornelissen, J.P. (2003) Metaphor as a method in the domain of marketing. Psychology and Marketing 20 (3): 209–225.

O'Malley, L. and Tynan, C. (1999) The utility of the relationship metaphor in consumer markets: A critical evaluation. Journal of Marketing Management 15 (7): 587–602.

Hunt, S.D. and Menon, A. (1995) Metaphors and competitive advantage: Evaluating the use of metaphors in theories of competitive strategy. Journal of Business Research 33: 81–90.

Berry, L.L. (1995) Relationship marketing of services: Growing interest, emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 236–245.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eriksson, K., Söderberg, IL. Customers’ ways of making sense of a financial service relationship through intersubjective mirroring of others. J Financ Serv Mark 15, 99–111 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2010.8

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/fsm.2010.8