Abstract

Banks and insurance companies maintain structural differences, limiting the extent of convergence due to factors such as demographics, the structure of liabilities, the scale of operations, regulation and accounting practices and distribution channels. Demography directly affects the needs of consumers regarding the risks to be covered; the structure of liabilities is important due to the limited possibilities to hedge many of them; the securitization process has been less relevant for insurance companies than for other financial intermediaries; regulation is different and implemented by different authorities; accounting is usually carried out on a price basis in the banking sector and on a cost basis in the insurance sector; and distribution channels require different expertise. A simulation model highlights the role of some of these factors and the peculiarities of managing insurance companies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Why are insurance companies different from other financial intermediaries? This apparently simple question is extremely relevant to understanding the current structure of the sector as well as to designing scenarios describing its evolution. It may seem strange to ask this question at a time characterized by continuous talks about convergence of banking, asset management and insurance activities. Fashionable examples involve: application of new asset management techniques to manage reserves of traditional insurance companies, increasing cross-selling efforts of insurance and financial products by both insurance companies and banks, modification of products sold by insurance companies to include financial elements which could traditionally be found only in products offered by banks and investment houses. Other forces pushing towards convergence are associated with regulation and accounting procedures, for example the Financial Conglomerates DirectiveFootnote 1 and the decreasing heterogeneity of accounting rules.

In this paper, we do not deny the existence of this multidimensional convergence process involving financial innovation, distribution channels and regulations. However, we claim that some forces that are usually interpreted as indicators of convergence might not be as stable as believed. Our main point is that banks and insurance companies maintain structural differences, limiting the extent of convergence. These specific factors are: demographic issues, the structure of liabilities and the scale of operations.

Before studying these elements in detail, we notice that the evolutionary landscape of financial markets seems to be consistent with the idea that insurance companies are different. Both insurance companies and other financial intermediaries have been suffering from the development of new financial products, often associated with securitization.Footnote 2 However, the process of financial innovation has perhaps been more challenging for commercial banks. To see this, one needs only think of the development of (a) the money market allowing mutual funds to substitute banks in the provision of liquidity; (b) financial equity derivatives threatening mutual funds as providers of diversification to final investors and (c) a market for mortgages allowing mutual funds and pension funds to finance the long-run needs of would-be homeowners. New intermediaries have been created to exploit this process, for example financial divisions within automobile companies to provide auto loans.

Insurance companies have been on balance positively affected by securitization and the process of financial innovation, which have extended the possibility of spreading the risk of large natural catastrophes through bonds. New intermediaries have provided insurance against default of municipal bonds, where policies are sold to the issuer municipality which attaches them to the bonds then receiving an AAA rating.Footnote 3 However, no financial intermediary seems to have used the benefits of securitization to enter the traditional markets for insurance products. Moreover, insurance contracts have been less touched by the securitization process, perhaps because of the adverse selection problem and of the peculiarity of the “insurance know-how” in terms of risk pricing and management.Footnote 4 This provides further proof about the specific identity of insurance companies.

The paper is organized as follows: After a brief analysis of convergence and its limits contained in the following section of this paper, the next section will discuss insurance and finance from the point of view of the investors. The subsequent section will deal with insurance and finance from the point of view of the suppliers. In the penultimate section, we will discuss the differences among insurance companies, banks and asset managers associated with differences in liabilities and scale of operations. The last section will conclude by stressing policy implications. The Appendix contains a simulation model that will be used to empirically explore a few of the relevant elements highlighted in the main discussion.

Insurance companies and other financial intermediaries: true convergence?

Various developments in financial markets are often mentioned as examples of a convergence process in the management and operations of insurance companies and other financial institutions. Among these examples the most relevant are:

-

application of new asset management techniques to manage reserves of insurance companies. The increasing number of insurance companies investing their own capital in hedge funds is a visible example regarding the structure of proprietary portfolios;

-

increasing full-function joint venturesFootnote 5 in life and non-life businesses between insurance and banking financial groups;

-

modification of products sold by insurance companies to include financial elements traditionally found only in products offered by banks and investment houses. Unit-linked and index-linked products usually require passively or actively managed assets or mutual funds to act as underlying securities. Through unit-linked and index-linked products, insurance companies may then sell financial securities under the form of insurance products. In several countries this is perhaps the most visible aspect of the convergence process and is the basis of many discussions about the necessity of a “level playing field” between commercial banks and insurance companies and the convergence of regulation.

There are more forces pushing towards convergence, due to regulation and accounting procedures:

-

The Financial Conglomerate Directive represents the first international application of the recommendations on the supervision of conglomerates adopted by the Group of 10 under the supervision of the Bank for International Settlements. The Directive (a) introduces specific rules for financial conglomerates so as to amplify the prudential legislation for credit institutions, insurance companies and investment firms and (b) provides for the establishment of a single supervisory authority to coordinate overall supervision of a conglomerate.

-

Traditionally, banks and insurance companies were widely different due to price-based and cost-based accounting rules. However, this source of difference is decreasing, albeit incompletely. Since 2005, European insurance companies have been using International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS-4) involving market-based rules for determining balance sheets. However, the adoption of international accounting principles has induced some differences in the evaluation of assets and liabilities, as the latter keep being evaluated by means of the traditional local gap criteria. We have explored convergence of accounting rules and its implication for insurance companies in Beltratti and Corvino.Footnote 6 Allen and CarlettiFootnote 7 explore the implications of mark-to-market accounting for the stability of the banking sector.

In this paper, we do not deny the existence of such a multidimensional convergence process, involving financial innovation, distribution channels and regulation. However, we notice that some forces that are usually interpreted as strong convergence signals may be more apparent than real. Our main point is that – in principle – banks and insurance companies maintain structural differences which limit – in practice – the extent of this convergence. Such differences go beyond the modifications to the regulatory and accounting framework and – focusing on life insurance – are especially related to elements like the centrality of demographic issues (the life insurance source of underwriting risk), the differences associated with the structure of liabilities and the different impact of the scale of operations.

Insurance and finance from the point of view of the final investor

There are strong connections between insurance products and financial products in a stylized model of investor choice. According to the standard description, a rational investor acts on the basis of a long-run planning horizon, taking into account several sources of uncertainty that may undermine his financial wealth and therefore his well-being. Here is a list of some sources of uncertainty:

-

labor income uncertainty: the investor is also a worker who may be subject to uncertainty about wage and/or about the amount of time spent working (unemployment being a particularly negative event);

-

family uncertainty: the investor often lives within a family. This may provide a sort of spontaneous insurance against negative states of nature, for example if there is low or negative correlation between his income and the income of other people in the family. On the other hand, a family also creates new sources of uncertainty associated, for example, with the support of other household members and the necessity to invest future resources (with highly uncertain returns) in the education of children;

-

health risk: both the investor and other members of the family are subject to the risk of deterioration of health, and death;

-

consumption risk: the current and future level of consumption may be at risk as a consequence of the previous risk factors or other risk factors of temporary or permanent nature;

-

house risk: the house represents the largest part of wealth for most families but fluctuations in its value are usually not insured and expose overall wealth to the risk of fluctuations. Moreover, houses are usually purchased through mortgages which expose the household to new sources of risk, for example interest rate risk.

In virtually all cases, risk manifests itself as a bad state of nature, one in which income or wealth falls considerably because of exogenous events. In all cases, a high level of wealth is a way to absorb the consequences of such states of nature with minimum damage. Accumulation of wealth and its consequent investment in financial assets creates, of course, new sources of financial risk, which may affect the growth path of wealth over time. Such risks are well-known and need not be mentioned here.

To most families, maximizing the rate of growth of wealth is not enough to hedge against future states of nature. Most families will never achieve a level of wealth that is so high as to make risky states of nature almost irrelevant in utility terms.

Insurance products are therefore needed in order to protect oneself from well-identified risk sources. Buying protection against risks is useful from the point of view of the overall planning problem. To a rational, long-term investor, the portfolio that maximizes long-run well-being is equivalent to the portfolio that minimizes the fluctuations of consumption over time. The rational investor selects securities with the goal of stabilizing consumption across states of nature. In determining expected returns, investors should require a lower premium to hold securities which are uncorrelated with the market and may therefore provide a natural insurance against the events of market downturn.

From the point of view of demand, then, it is not relevant to separate insurance policies from financial products. Insurance and finance mix to determine an optimal portfolio of securities minimizing volatility across states of nature and maximizing expected returns. Risks can certainly be categorized differently. Perhaps a useful starting point is to distinguish between risks which are observed more or less continuously, such as fluctuations in the prices of assets, and risks which are observed discontinuously. In several cases, hedging of discontinuous risks may be obtained through products supplied by insurance companies. Quoting from Booth et al. Footnote 8: “Life insurance companies provide a vital financial service to individuals and to firms who wish to insure themselves against financial losses which might be incurred as a result of any of the following: (a) death; (b) survival to a particular time or over a particular period; (c) sickness or disability”. Nowadays, such demographic issues are more pervasive than ever due to increased life expectancy. A longer life is associated with the need to protect long-term consumption risks. Quality of life is also a relevant factor that requires purchase of insurance products. Such demographic differences are a permanent and probably expanding factor, differentiating banks and insurance companies.

To understand the limits of convergence between insurance companies and other financial intermediaries, we have first to understand which characteristics (from the point of view of the supplier) make it convenient to offer different classes of products covering different classes of risks. Is a financial intermediary offering a product covering a specific risk in the best possible position to also offer a product covering another risk? What characteristics are relevant from the point of view of the supplier?

Insurance and finance from the point of view of the supplier

In comparing insurance companies and other financial intermediaries we will refer to the functional perspective as opposed to the institutional perspective.Footnote 9 As Merton states:

One perspective takes as given the existing institutional structure of financial intermediaries and views the objective of public policy as helping the institutions currently in place to survive and flourish. Framed in terms of the banks, or the insurance companies, private-sector managerial objectives are similarly posed in terms of what can be done to make those institutions perform their particular intermediation services more efficiently and profitably. An alternative to the institutional perspective – and the one we take here – is the functional perspective. The functional perspective takes as given the economic functions performed by financial intermediaries and asks what is the best institutional structure to perform those functions. In contrast to the institutional perspective, this functional perspective does not posit that existing institutions, whether operating or regulatory, will necessarily be preserved. Instead, its structure rests on two basic premises: (1) financial functions are more stable than financial institutions – that is, functions change less over time and vary less across geopolitical boundaries; and (2) competition will cause the changes in institutional structure to evolve toward greater efficiency in the performance of the financial system.

The functional perspective rests on the idea that financial institutions exist to solve the problems of consumers. Technological innovations, changes in regulations and competition may change the range of activities and products associated with a specific intermediary, but the intermediary will always try to help consumers to solve their problems. This is the reason why a study of convergence must start from the demand side, as we have done in the previous section. A financial intermediary trying to solve a specific class of needs on the part of the consumers will specialize in specific financial tools.

Economic theory, coherently with the development of the functional perspective, stresses that financial intermediaries are less and less explained by traditional elements such as transaction costs and asymmetric information. Transaction costs have decreased over time but the role of financial intermediaries has increased. Allen and SantomeroFootnote 10 point out that financial intermediaries have an increasing role as facilitators of risk transfers and as experts in dealing with the growing complexity of financial markets. By repackaging complex securities into assets with more stable and predictable cash flows, they may encourage participation in risky investments on the part of risk-averse individuals.

Products that provide wealth in specific states of nature and are triggered by specific events are mainly provided by insurers. Specific events may be defined in terms of what happens to a single individual, for example death, or in terms of what happens to a group of people or companies, for example insurance against general climatic events. Traditional insurance products are sold by companies which exploit the law of large numbers. By insuring risks which are independent across a large population, and by charging a fair premium to each member of the population, they can control the overall rate of inflows and outflows and obtain a profit.Footnote 11 Insurance companies issue customized insurance contracts and invest the proceedings in assets that are coherent with the profile of the liabilities. In doing so, insurance companies are different in several ways, such as in the areas of secondary markets and securitization, regulation and accounting practices, distribution channels, and asset management.

Secondary markets and securitization

An important element distinguishing insurance companies from several other financial intermediaries is the lack of a secondary market where the contracts written by insurance companies may be traded. The holder of a financial product issued by a different intermediary, for example a structured product issued by an investment bank or a bond issued by a non-financial company, can sell the product in secondary markets with varying degrees of liquidity. Even banks can sell their loans to third parties due to improvements in securitization. However, the holder of an insurance policy can only obtain payments from the company that has issued the policy. The holder cannot sell his insurance policy to a third final investor.

Of course, this does not imply that the insurance company needs to maintain the risk on its balance sheets. The company may well decide to sell this risk to financial investors through a securitization. As CumminsFootnote 12 notes: “the securitization process involves the isolation of a pool of assets or rights to a set of cash flows and the repackaging of the asset or cash flows into securities that are traded in capital markets”. The insurance company may then decide to separate a few well-defined sources of risk and package them into securities which are then bought by investors searching for assets with risks that are uncorrelated with the market. There are several sources of such risk in the balance sheets of insurance companies, for example demographic risks associated with mortality and longevity, or catastrophic risks connected with natural events. CumminsFootnote 13 describes many advantages of the securitization process, for both insurers and capital markets in general.

However, the proportion of securities created through securitization activities has mainly arisen out of business not directly emerging from insurance companies. Rather, the main sources of securitization have been mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities associated with auto loans, consumer credits and similar. The potential arising from the very large pool of assets and liabilities of insurance companies has been exploited very little. It is difficult to explain this without a theoretical model, but certainly problems connected with moral hazard and adverse selection may have a large role.

This reinforces our point: differences in the fundamentals of the business models of insurance companies and other financial intermediaries have led to different operational structures. Moreover, the lesser role played by securitization in the insurance industry implies that the originate-and-distribute model prevailing in the banking industry in the last several years has not been predominant in the insurance industry. While banks have relied on their ability and skills to originate loans with the purpose of then passing the risk to other investors, insurance companies have usually kept the risk on their balance sheets, trying to manage it through asset and liabilities choices. For example, mortality and longevity risks have not been separately sold to other investors, but have to some extent hedged each other in the balance sheets. The differences between the insurance companies and banks were very clear during the crisis of the summer of 2007. Many assets related to securitization carried out by banks have seen large drops in their values due to fundamental and liquidity reasons. Some banks and investment banks have been hit as buyers of mortgage-backed securities. It is likely that several insurance companies have also been hit as investors. However, what is crucial to the discussion of this paper is that some banks have suffered not as financial investors, but as followers of the originate-and-distribute model. The liquidity crisis has basically stopped several markets from functioning efficiently and has frozen the possibility to sell loans and other asset-backed securities, dislocating the business model on which banks have relied for several years. This dislocation has, of course, reflected itself in the level of operating profits. Similar dislocations have not been observed for insurance companies, which do not rely so strongly on external capital markets to obtain flows of continuous new capital to invest in the business. Again, this points to basic differences between insurance companies and other financial intermediaries.

Regulation and accounting practices

Regulation and accounting practices may also affect the degree of convergence. Different regulations and accounting practices certainly prevent the extent of convergence.

To an institution offering both financial products and insurance products, the impact of regulation and accounting may be a relevant cost factor preventing complete merging of activities which could technically be performed at the same time. For example, the existence of cost-based accounting prevents a supplier from jointly treating financial products and insurance products in its books and requires a separation of procedures.

The insurance industry has recently been touched by some regulatory transformations whose impacts cannot yet be predicted (some of them are already in force, others will become effective in the near future). Among these transformations, we should at least recall:

-

The Financial Conglomerate Directive: It represents the first world application of the international recommendations on the supervision of conglomerates adopted by the Group of 10 under the aegis of the Bank for International Settlements. The Directive introduces specific prudential legislation for financial conglomerates so as to amplify the sectoral prudential legislation for credit institutions, insurance companies and investment firms and provides for the establishment of a single supervisory authority to coordinate overall supervision of a conglomerate and organizes the way in which that authority exercises its responsibilities.

-

The IASB insurance project Footnote 14: This project has not yet been completed, but it will homogenize the balance sheet evaluation methods for assets and liabilities of insurance companies, banks and asset managers by amending the accounting rules adopted in the insurance industry (in particular, with reference to liabilities).

-

The Solvency II project by CEIOPS Footnote 15: This project, which has not yet been completed, will lead to a sort of homogeneity in evaluating the risk capital of insurance companies and banks by modifying basic principles for calculating the regulatory capital requirements in the insurance industry.

At first sight, the principal aim of all these changes seems to be the standardization of the evaluation criteria and of the financial performance calculation models across financial institutions. With particular reference to insurance companies, this may be done by modifying the evaluation criteria for assets and liabilities and the procedures of risk assessment. But this standardization may not be feasible. The aforementioned projects are going to require insurers to estimate the risk margin as a consequence of the uncertainty associated with their liabilities.Footnote 16 In order to do it, insurers need rules and assessment models specially conceived for insurance companies, which are able to take into full consideration liabilities' features and size. The introduction of the projects with no modifications could paradoxically produce an increasing differentiation making insurers, banks and asset managers less, rather than more, similar.

Dickinson and LiedtkeFootnote 17 provide a survey-based empirical analysis of the views of 40 leading international insurance and reinsurance companies on the likely impact that an international financial reporting standard based on full fair value methodology would have on companies. Among other interesting results, they point out that a full fair reporting system would have adverse impacts on the economic role of insurance companies and would change business strategies.

Distribution channels

Life insurance products are sold through individual agents whereas general insurance products are sold through individual agents, corporate agents and brokers. There are some apparent long-run trends in the relative importance of the various channels, for example the reduction of the role of individual agents in the U.S. or the increase of corporate agents (particularly bank-led channels like bancassurance) in Europe. However, the different channels have coexisted for a long time and continue to do so. This is interesting due to the different cost structures of the channels and the presence of innovations, such as the Internet. However, Dumm and HoytFootnote 18 point out that the Internet has not substituted traditional channels but rather has been used as an instrument for contacting consumers. Moreover, differential costs can coexist in equilibrium if they provide differential benefits to the final customers, mainly in terms of clarification of the details of the sometimes complex insurance products.

Bancassurance is an obvious example of convergence between banks and insurance companies. It is associated with the idea that one-stop shopping may be a crucial point in the selling proposition of modern insurance companies. There are several reasons why insurance companies may be interested in bank-led distribution channels. Insurance companies may hope to exploit the important competitive advantage of banks, consisting of the wide customer base, the many available branches and the stickiness of the relations between banks and clients, and at the same time save on the large training and maintenance costs associated with a captive distribution channel.

The possibility of using banks to sell insurance products is crucially related to the skills which are needed to inform and assist the consumers. If insurance products and financial products were perfect substitutes, there would be no main problems using a unique distribution channel. A unique channel would prevent duplication of efforts and would increase private and social efficiency.

The evidence is mixed however. One-stop shopping is not equally popular in different countries, questioning the sustainability of the idea to jointly sell insurance and financial products. In Continental Europe, most life insurance products are sold through captive channels such as tied agents and through banks rather than through advice-based channels like brokers or financial advisers. This facilitates cross-selling of products, even though the profitability of such efforts is limited by the fact that more affluent customers tend to prefer adviser channels. However, property and casualty products are not widely sold through banks, which is also true in the European case. This may well be due to the fact that the skills of the salesforce that are necessary to sell insurance products may be different from the skills that are needed to sell financial products.Footnote 19 To make cross-selling efforts effective, the sale of insurance products needs to be supported by more and better training, especially as the non-life insurance products (e.g. motor, health, long-term care) are concerned.

There is a difference between the demand for insurance products and for financial products. The former require a specific culture and are based on the willingness and capability to adopt a truly forward-looking attitude to the solution of the overall financial problem highlighted in the previous section. The latter are more heavily affected by fads and transitory components associated with perceived valuation errors on the part of the markets. Moreover, the structure of demand differs widely depending on the type of insurance products under consideration. In the property and liability sector for example, demand comes largely from the corporate sector. The choice about distribution channels cannot ignore the different identity of the demand. These are reasons why the process that leads to the sale of the two products requires different skills and different attitudes towards the clients.

From a strategic point of view, the choice of whether to distribute insurance products mainly through bank-led channels or through captive channels is of fundamental importance to insurance companies. It amounts to deciding whether the value-creating activities of insurance companies expand to both production and distribution of products or whether companies decide to be providers of products and choose for themselves an engineering role of devising and managing new products. Evidence from the asset management industry shows that pure asset managers are indeed profitable but in a very cyclical way. Increasing the role of bank-led channels in the distribution of insurance products may therefore not necessarily reduce the profitability of insurance companies but may make profits less stable over time. This could in turn cause a significant repricing of insurance companies stocks.

Asset management

Insurance companies have increased their role as asset managers. The development of unit-linked products has allowed insurance companies to sell financial products wrapped in the context of typical insurance products. Especially in European markets, the products included in the wrapped structure have consisted of internally managed mutual funds.

Moreover, many insurance companies have adopted an active style in managing their own reserves. While traditionally such reserves have been invested in fixed income assets, there has been a recent wave of investment in equities and alternative assets like hedge funds.

It is well-known that asset management is a sector characterized by various economies of scale. Moreover, active asset management requires increasingly sophisticated skills. Many insurers manage assets through outsourcing due to increasing complexity of asset management techniques and the search for higher returns in a low interest rate environment. External asset managers can better exploit economies of scale and offer competitive management products and services. In Europe outsourced insurance assets amount to less than $200 billion in 2006 but are projected to grow to $800 billion by 2011.Footnote 20

Liabilities and size

In this section we explore the role of liabilities and size because these will be the main characteristics that we will study in our simulation model.

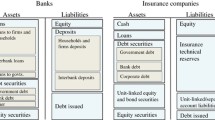

The asset and liability problem of insurance companies and other intermediaries

A key difference between insurers and other financial intermediaries, bankers and asset managers lies with some aspects of their liabilities.Footnote 21 More precisely, insurers' liabilities share with the long-term liabilities of other institutions (i.e., bonds issued by a financial or non-financial company) the duty to pay fixed (as in the case of capital redemption or fixed coupons) or indexed (as in the case of floating rate coupons) amounts of money but do not share the certainty of the timing of the future fixed or indexed cash flows, due to uncertainty about the moment in which the event causing the payment will happen and due to the possibility of early redemptions in the absence of a secondary market. In several cases even the amount of the liability and the time and amount of premiums (as in the case of recurring premium products) are uncertain, magnifying the specificity of insurers' liabilities.

This similarity to the characteristic of various financial assets may appear to back the story of a convergence of insurance companies and other financial intermediaries. But that is not true. Many financial institutions, for example investment banks, manage their liabilities by building up a hedging portfolio of financial assets able to replicate the liabilities' profile (risk hedging); since the timing of cash flow is certain and the factors of uncertainty are only financial factors, it is possible to manage a portfolio able to replicate the dynamics of liabilities. Insurers cannot do that; when the timing of cash flows is uncertain and since the risk factors may not necessarily be traded it is not possible to build a hedging portfolio of financial assets that is able to replicate the liabilities' profile.

Insurers face their liability in a completely different way, that is, pooling a large group of similar risks so that the accidental losses become – in accordance with the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem – predictable within narrow limits (risk pooling).

In other words, while the art of banking is building up a “good” asset portfolio in order to match liabilities (or changing liabilities in order to match assets), the art of an insurer is building up a “good” liabilities portfolio in order to apply the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem and then estimate the average losses. As a consequence, while the core risk of a banker is the mismatch risk, the core risk of an insurer is the underwriting risk, that is, the risk that an insurer suffers losses because the actual average losses are higher than the expected ones.

The recent financial crisis has provided important evidence about the mismatch risk of banks, showing that such a risk is heavily dependent on valuation uncertainty of the assets. The British bank Northern Rock has seen a traditional bank run caused by depositors who were uncertain about the valuation of the assets of the bank, largely invested in mortgages. Uncertainties about the ability to pay on the part of the borrowers has caused the run on deposits.Footnote 22 In this case the mismatch risk was associated with a market risk. Formal guarantees provided by the government has calmed investors, but the bank's operations have not become normal due to the mismatch between assets and liabilities and the need to use the money market to provide short-term funds. The bad functioning of the money market, however, has prevented Northern Rock from borrowing for several weeks, with severe damages to the profitability of the bank. In turn, the money market was not functioning normally due to a general fall in confidence among financial institutions about the solvency of the other financial institutions, a fall associated with uncertainty about the strength of balance sheets. Countrywide Financial, the U.S. mortgage lender, has also been affected by a mismatch between assets and liabilities.

The relevance of the scale of operations

In the case of insurers, risk per unit of financial portfolio decreases by increasing the volume of activity. An investor (e.g. an investment bank) having an assets/liabilities portfolio with the same weights of the assets/liabilities portfolio as a second investor but one thousand times bigger, has a risk one thousand times bigger. An insurance company having an assets/liabilities portfolio with the same weights of the assets/liabilities portfolio as a second insurance company but one thousand times bigger, has a risk lower than one thousand times that of the previous one. In order to estimate the value and risk of an insurer, one cannot leave the insurer dimensions out of consideration.

The difference between insurance companies and asset managers is even more evident. Since asset managers by definition maintain a perfect balance between assets and liabilities, they do not need to estimate the timing of their future cash flow in order to build up an asset allocation able to finance their liabilities. Asset managers are used to optimizing their portfolio just over an investor's hypothetical time horizon, but they do not have to do anything to estimate the actual time horizon. If clients change their mind and redeem their investment earlier than expected, asset managers just have to sell the related assets and pay back what results from the sale.Footnote 23

Insurers, on the contrary, have to optimize their portfolio not over a hypothetical time horizon, but over the expected time horizon, since their liabilities are not just linked to the market value of their assets, but to exogenous drivers (e.g., agreed benefits, suffered damages, guarantee capital, etc.). To summarize, insurers estimate the expected time horizon of their investments by pooling a large group of similar risks so that the time of accidental losses driving their cash flows (i.e., death in life insurance) become – in accordance with the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem – predictable within narrow limits.

In other terms, while the art of an asset manager is building up a “good” asset portfolio in order to match a hypothetical liability, the art of an insurer is building up a “good” asset portfolio in order to match a real liability.

As a consequence, while the core risk of an asset manager is the reputation risk, the core risk of an insurer is the underwriting risk, that is, the risk that an insurer suffers losses because the actual timing of its losses differs from the expected one. In order to separate the underwriting risk due to potential errors in estimating the actual losses from the underwriting risk due to potential errors in estimating the actual timing of losses, we will refer to the first one as “cash flow risk” and to the second one as “timing risk”.

Clearly, the relevance of the scale of operations is not equivalent to the existence of economies of scale for the insurance industry as a whole. If economies of scale were so strong, we should have observed a process of increasing concentration. However, such a concentration has not been observed. The reason for that could probably be found in the “non-uniqueness” of risk pooling as the instrument by which insurance companies can reduce risk. As a matter of fact, the insurer can also support the typical risk-pooling activity with hedging (e.g., through reinsurance) and risk-spreading, that is, by underwriting groups of non-similar risks or by fully diversifying his business.Footnote 24

Berger et al. Footnote 25 compare the conglomeration hypothesis (claiming that owning and operating a broad range of businesses can add value from exploiting cost-scope economies by sharing inputs in joint production or taking advantage of revenue-scope economies) and the strategic focus hypothesis (claiming that value is maximized by focusing on core businesses and competencies) for U.S. insurance companies. They find no clear winner between the two hypotheses; both seem to explain some strategic choices of different firms coexisting with different scales of operations and focus in the long run.

Relevant results of our simulation model

Among the interesting results, the first is the nonlinear relation between volatility of liabilities and the value at risk (VaR). When volatility doubles from 0.5 to 1 the VaR also doubles, but then when volatility increases from 1 to 3 the VaR increases less – it actually only approximately doubles. When volatility again grows from 5 to 15, the VaR only goes up by about approximately 10 percent. There is therefore a concave relation between VaR and volatility.

This can be explained on the basis of the following intuition: the worst scenarios are those combining an early call on the liability together with an increase in interest rates. The former implies an outflow that is larger than the nominal value of the liability (because the asset did not have enough time to grow to the tight value) while the latter decreases the value of the portfolio that the insurance company liquidates in order to redeem the liability.

The second interesting result is that the mean of the distribution, representing the value of the company, increases with volatility. This counterintuitive result is associated with our hypothesis of a positive slope of the term structure of interest rates. Since the positive slope of the term structure of the spot interest rates implies a positive slope for the term structure of forward interest rates, it follows that interest rates tend to increase in our scenarios. Increasing interest rates tend to be associated with capital losses for scenarios of early redemptions of the liability and with increasing reinvestment revenues for scenarios when redemption occurs after the eighth year, also due to our hypothesis that the increase in the value of the liability after the eighth year is smaller than the short interest rate at which the proceeding of the sale of the portfolio is invested.

Increasing volatility affects the occurrence of extreme redemption events. However, extremely negative events, corresponding to early redemption of the liability, tend to have a less than proportional impact on value, whereas extremely positive events, corresponding to late redemptions, tend to contribute positively to the value of the firm. The difference is due to the changing nature of the investment strategy of the insurer: from the beginning to year 8 the insurer buys a zero coupon bond which is held until maturity (provided the liability does not mature unexpectedly earlier than that), but then there is a switch to a strategy of rolling over the short-term interest rate. While the costs of early selling of the bond are stable, the benefits of rolling over increasing interest rates increase.

When the term structure is flat, the new result is connected with the negative relation between volatility and the value of the insurance company in the presence of a flat term structure. Since the flat slope of the term structure of the spot interest rates implies an equal term structure of the forward interest rates, it follows that interest rates tend to remain stable in our scenarios. As in the previous case, stable interest rates tend to be associated with capital losses for scenarios of early redemptions of the liability and with positive reinvestment revenues when redemption occurs after the eighth year. It follows that the timing risk introduces a relationship between the shape of the term structure of the interest rate and the value and the risk profile of an insurance company.

Conclusions

Despite the convergence process among different financial intermediaries, we claim that there are structural differences at work that maintain the specificity of insurance products and insurance companies. Financial products and insurance policies are often different from the point of view of the needs of the consumers. Moreover, the asset- and liability-management problem of insurance companies is different from that of banks and of asset management houses. We have tried to give substance to this general discussion by making use of a simple simulation model with two basic sources of uncertainty: the level of the interest rate and the realized maturity of a liability. The simulations make the following points:

-

1

Even leaving the most intuitive cash flow side of the underwriting risk out of consideration, companies face a severe underwriting risk associated with surprises in the timing of liabilities, with the monetary effects of this underwriting risk being a function of market conditions and of the assumed investment strategy.

-

2

The scale of operations is also important, especially when correlations among the various liabilities are low.

Other conclusions can be derived from the simulations. The first has to do with the relation between hedging and the impact of uncertainty about the maturity of the liabilities. The impossibility to perfectly hedge the liabilities makes it impossible to define an a priori “hedging” financial strategy. Economic theory has highlighted several variables that are relevant to the choice of managers about hedging, such as managerial self-interest, nonlinearity of taxes, costs of financial distress, and existence of capital market imperfections.Footnote 26 Under certain conditions, hedging may be undesirable, see for example Grundl et al. Footnote 27 who study the implications of demographic risk on the optimal risk management mix for a limited liability insurance company and show that hedging may sometimes destroy shareholder value. It follows that the evaluator of an insurance company must make specific assumptions about financial strategy.

The second has to do with the relevance of market conditions in determining the value of an insurance company. The slope of the term structure, and the associated expected and actual dynamics of short-term interest rates, have an impact on the value of an insurance company again through the financial strategy, that is, an initial purchase of a long-term bond with a maturity corresponding to the expected duration of the liability and the subsequent roll-over in short-term instruments. Increasing uncertainty about the liability may have a positive or negative effect on value depending on the slope of the term structure.

The third has to do with the nonlinear relation between uncertainty about maturity of the liability and the VaR of the company. This nonlinearity results from complex interactions between the dynamics of interest rates and possible early redemption of the liabilities. This result suggests that simple VaR modeling of risk may not be sufficient to determine risk for an insurance company.

Finally, our simulations highlight the role of the salesforce through which insurance policies are sold. The salesforce is very important for an insurance company because of its role in providing information that is useful to estimate the timing of the liabilities, which in turn is crucial to determine the right asset and liability policy.

This interaction between consumers' decisions, liabilities and asset policy is a fascinating research question that distinguishes insurance companies from other intermediaries. It implies the necessity to use simple but complete models to determine both value and risk. In future work we plan to further explore this rich interaction.

It is also important to stress the policy implications of our work:

-

Following the functional perspective, we emphasize the wide role of insurance companies in helping investors solve their complex financial optimization problem. Insurance companies may: (a) help investors understand the increasingly complex risks and opportunities faced by investors in the marketplace; (b) develop new products which help investors to smooth consumption across time and across states of nature particularly as far as discrete (e.g. health risks) and long-run (e.g. pension needs) risks are concerned; and (c) use appropriate investment and risk management techniques to maximize their value in the long run and therefore benefit policyholders and shareholders.

-

To exploit scale of operations where it is possible to do so, for example in the non-life business, and specialize in niches where scale is not crucial or where it may be even dangerous. The dimension and scope of the salesforce is one of the crucial elements in this respect. The salesforce is important in communicating the right use of products to the investors and in attracting the right clientele. It is also important to the insurance company in clarifying the true dimension of uncertainty about the duration of the liabilities, a characteristic that is crucial for determining the optimal asset allocation policy. However, having a salesforce distributing both traditional insurance products and financial products (or versions of the traditional products extended to allow for increasing degrees of financial content) may result in large costs, due to the extensive training that is necessary to explain to clients both the insurance and the financial components of the products. Each insurance company will have to verify whether cross-selling is effective and compare the benefits with the costs of the salesforce.

-

Insurance companies have a unique role as absorbers of risks that cannot be hedged. This is crucial to the welfare of companies and individuals. Clearly, insurance companies need to be very smart in devising an asset allocation policy that is coherent with the expectations of stakeholders and at the same time guarantees enough wealth to cover all the necessities of policyholders. Continuous improvements in asset management techniques will therefore be a crucial source of value creation, in the context of a strict control of risks.

Notes

Directive 2002/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the supplementary supervision of credit institutions, insurance undertakings and investment firms in a financial conglomerate.

Merton (1995) writes that “Greatly reduced trading costs would be expected to cause transaction volume in financial markets to rise substantially, which it has. But, these reductions in costs more generally have contributed to an even greater expansion in markets through the process of ‘commodization’ in which financial markets replace financial intermediaries as the institutional structure for performing certain functions”.

Such companies have been severely affected by the recent financial crisis because of their expansion beyond simple insurance of debt issued by U.S. municipalities to also include asset-backed bonds and collateralized debt obligations. See Scholtes (2007).

“With regard to the development of the transfer of insurance risk to the money and capital markets, […] for investors the problem is one of liquidity, namely, that even if they wish to sell insurance-linked securities in the market, selling them is difficult. Behind this is the fact that there are few experts able to analyze insurance risk and that the market is not very big, so that even if experts are hired, it would be impossible to pay their costs. Given these elements, it would seem that investment in insurance risk is still in its infancy.” See Sompo (2007).

See the Commission Notice on the concept of full-function joint ventures under Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 on the control of concentrations between undertakings.

See Merton (1995).

Of course there are mixed cases, for example whenever the payment of a payoff is triggered by an outcome defined in terms of a specific event, such as death, but the value of the payoff is associated with financial market dynamics. The increasing pervasiveness of finance and the results of many efforts of financial innovation trying to complete markets produce an ever-widening possibility of creating mixed products.

Ibid.

“The objective of including a risk margin in the measurement of an insurance liability is to convey useful information to users about the uncertainty associated with the liability”. See IASB (2007b).

As one of the comments that we received on an earlier draft of this paper effectively states: “The fact that a car-maker sells little toys in his repair shops does not mean that there is a great convergence between the automotive and the toy industry. It only shows that shared or doubly exploited distribution channels make sense or that one product might be a nice add-on or tie-in with another”.

See Cummins (1992).

Runs are impossible in the case of insurance companies. At most, policyholders can stop paying their premium and as a consequence lose coverage.

The existence of transaction costs may affect the following: an asset manager receiving an inflow of money needs to be careful before investing it, for example in stocks because the inflow may be partially or totally offset by a future outflow. By keeping liquidity, the asset manager may decrease transaction costs but only by increasing the tracking risk, that is, the volatility of the differential between the rate of return of the portfolio and the rate of return of the benchmark. The progressive reduction in transaction costs associated with better technology has, however, reduced this concern.

The use of risk-spreading of course depends on the evolution of the risks that society wants to hedge. Mortality risks associated with terrorism may, for example, dramatically increase the correlation of risks from the point of view of insurance companies, with a consequential increase in the amount of risk capital. Doherty and Schlesinger (2001) decompose insured losses into several components to illustrate the relevance of correlated and specific components of risk and analyze the relevance of securitization as a tool to transfer risk and decrease the need to maintain capital.

This is a perfect match in the case of the issuer of a standard financial product characterized by a secondary market. In this case, investors who want to redeem the product may simply sell it to someone else on the secondary market, without interacting with the issuer. This is obviously not true in the case of an insurance product without a secondary market, which needs to be redeemed by the insurance company itself.

The Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model is able to capture this effect. The CIR model is based on the hypothesis of mean reversion of the short rate to the equilibrium rate. The equilibrium rate is larger than the short rate when the slope of the curve is positive.

The CIR model is able to capture this effect. The equilibrium rate is equal to the short rate when the slope of the curve is flat.

For the sake of simplicity, we assume investment in a government bond and therefore ignore any consideration associated with the impact of credit risk on the value of the issuer.

References

Allen, F. and Carletti, E. (2006) Mark-to-market accounting and liquidity pricing, CFS Working paper series 2006/17, The Wharton School, Philadelphia.

Allen, F. and Santomero, A.M. (1998) ‘The theory of financial intermediation’, Journal of Banking and Finance 21: 1461–1485.

Beltratti, A. and Corvino, G. (2007) ‘Potential drawbacks of price-based accounting in the insurance sector’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 32: 163–177.

Berger, A.N., Cummins, J.D., Weiss, M.A. and Zi, H. (2000) Conglomeration vs. strategic focus: Evidence from the insurance industry, Working paper 99-92-B, The Wharton School, Philadelphia.

Booth, B., Chadburn, R., Cooper, D., Haberman, S. and James, D. (1999) Modern Actuarial Theory and Practice, New York: Chapman and Hall.

Cummins, J.D. (1992) ‘Financial pricing of property and liability insurance’, in G. Dionne (ed) Contributions to Insurance Economics, Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 141–168.

Cummins, J.D. (2004) Securitization of life insurance assets and liabilities, Financial Institutions Center Working paper 04-03, The Wharton School, Philadelphia.

Dickinson, G. and Liedtke, P.M. (2004) ‘Impact of a fair value reporting system on insurance companies: A survey’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 29: 540–581.

Doherty, N.A. and Schlesinger, H. (2001) Insurance contracts and securitization, CESifo Working paper no. 559, Munich.

Dumm, R.E. and Hoyt, R.E. (2002) Insurance Distribution Channels: Markets in Transition, paper presented at the 38th Annual Seminar of the international Insurance Society, Singapore.

European Commission (2007) Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the taking-up and pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance – Solvency II, COM(2007) 361 final, Brussels, 10 July 2007.

Financial Times (2007) ‘Insurers enlist third-party asset gurus’, Financial Times (2 July).

Grundl, H., Post, T. and Schulze, R.N. (2006) ‘To hedge or not to hedge: Managing demographic risk in life insurance companies’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 73: 19–41.

IASB (2007a) Preliminary views on insurance contracts, part 1: Invitation to comment and main text, Discussion paper (May), London.

IASB (2007b) Preliminary views on insurance contracts, part 2: Appendices, Discussion paper (May), London.

Merton, R. (1995) ‘A functional perspective of financial intermediation’, Financial Management 24: 23–41.

Scholtes, S. (2007) ‘Bond insurers feel the chill from credit turmoil fallout’, Financial Times (12 September).

Sompo (Japan Research Institute) (2007) Convergence of Finance and Insurance, Summary of the Proceedings of the Sixth Meeting, 2 February, Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We thank Silvano Andriani, Frederic De Courtois, Isabella Falautano, Dario Focarelli, Giampaolo Galli and Patrick Liedtke for comments on a previous version of this paper.

In this paper, we will use the word “intermediaries” to generally refer to institutions like commercial banks, investment banks and asset managers, and we will be more specific only when needed. However, we will not adopt the terminology often used in the insurance sector according to which intermediaries are represented by brokers and agents.

Appendix

Appendix

Modeling liabilities, portfolio structure and scale of operations

We use an analytical model to thoroughly study the following points:

-

1

The importance of the salesforce in terms of the correct communication of the liability risk to the insurance company, a piece of information that is crucial to estimate the maturity of the liability, and the ability of salespeople to prevent cases of early redemptions that are not due to modifications in the structural needs of the clients.

-

2

The asset and liability problem of insurance companies, as opposed to that of banks and asset managers, shows that the relevance of the underwriting risk and shows such a risk depends not only on demographic variables but also on financial variables and on the expected investment strategy.

-

3

The relevance of the scale of operations, by trying to measure the relation between timing risk and the scale of the portfolio.

To achieve these goals, we use a stochastic model describing:

-

the dynamics of liabilities,

-

the investment strategy of the company,

-

the dynamics of interest rates.

More specifically:

-

we assume that each liability:

-

is known ex ante in terms of its amount, which grows over time according to the factor

, where the rate i can be interpreted as an inflation rate for a non-life insurance product or as a minimum guaranteed for a life product. This hypothesis ignores cash flow risk and is uncertain in terms of timing as the maturity is normally distributed with an expected value equal to 8 and various alternative standard deviations respectively equal to 0, 5, 1, 3, 5, 8, 15. From now on we will refer to this standard deviation as “volatility”. Alternative standard deviations will be used to show that the VaR of a company may change as a function of the volatility of its liabilities which is in turn partially endogenous. To understand this point, imagine that the liability is represented by a standard insurance product investing in a fixed income portfolio. From the point of view of the insurance company, uncertainty about the liability depends on both uncertainty of interest rates and uncertainty about redemptions. Uncertainty (and therefore volatility) depends, therefore, on endogenous variables like the ability of salespeople to stabilize net inflows;

, where the rate i can be interpreted as an inflation rate for a non-life insurance product or as a minimum guaranteed for a life product. This hypothesis ignores cash flow risk and is uncertain in terms of timing as the maturity is normally distributed with an expected value equal to 8 and various alternative standard deviations respectively equal to 0, 5, 1, 3, 5, 8, 15. From now on we will refer to this standard deviation as “volatility”. Alternative standard deviations will be used to show that the VaR of a company may change as a function of the volatility of its liabilities which is in turn partially endogenous. To understand this point, imagine that the liability is represented by a standard insurance product investing in a fixed income portfolio. From the point of view of the insurance company, uncertainty about the liability depends on both uncertainty of interest rates and uncertainty about redemptions. Uncertainty (and therefore volatility) depends, therefore, on endogenous variables like the ability of salespeople to stabilize net inflows;

-

-

in terms of investment strategy, we have assumed investment in a zero coupon bond with a maturity equal to 8 years and a face value corresponding to that of the liability when evaluated after 8 years (the expected duration of the liability).Footnote 28 We also assume that:

-

if the liability occurs before the maturity of the bond, the bond is sold at the current market price;

-

if the liability occurs after the maturity of the bond, the company cashes in the face value of the bond after 8 years and then reinvests the proceeds at the risk-free rate (given by the risk-free rate of the Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model in our simulations);

-

the dynamics of the term structure of interest rates is described by the Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model. We have fitted the model in the case of an upward sloping curve and in the case of a flat curve. Comparing a flat and an upward sloping curve is useful to highlight the relation between the VaR of the insurance company and market conditions. Both the VaR and the value of the company depend on the joint dynamics of assets and liabilities.

-

We assume that the insurance company provides insurance against the liability, charging a fair premium equal to the value of the zero coupon bond.

Finally, we have assumed that the liabilities of the insurance company are given alternatively by 1, 25 and 50 elements whose total value was constant in such a way as to easily compare the results. This allows us to measure economies of scale and highlight the relevance of this element in the estimation of the capital at risk of the company.

The final result of each iteration is given by the gap, defined as the present value of the difference between the value of the assets and the value of the liability as measured at the time of occurrence of the liability (t n ). The present value has been computed on the basis of the interest rate, with maturity t n prevailing at time t 0. For simplicity's sake, we ignore the existence of a risk premium. The valuation derived from our simulation model is therefore larger than the one that would be obtained from a complete structural model. The result of each iteration will be described in terms of gap.

Early results are obtained by considering one liability, fixing the (positive) slope of the term structure and computing the above defined gap for six alternative values of standard deviation of the liability. This exercise allows for a measurement of the relation existing between the value of the company (taken as the mean value of the gap distribution), the VaR of the company (taken as the appropriate percentile of the gap distribution) and the volatility of liabilities.

We start with reporting some summary statistics for the distribution of the difference between actual maturity and expected maturity. These statistics will be useful for interpreting results shown in the following tables. Table A1 reports relevant moments of the distribution of the difference between actual maturity and expected maturity: It also shows that increasing volatility symmetrically increases the dispersion of the difference of actual and expected maturity. Most importantly, it shows that there is a nonlinear relation between the two variables. Increasing volatility from 1 to 3 has a dramatic effect on the percentiles, but moving from 3 to 15 has a much smaller effect.

Table A2 reports results regarding the mean, the mode and some relevant percentiles of the distribution of the gap. The percentiles can be interpreted as the most negative occurrences for the value of the insurance company.

There are two interesting results that we would like to discuss regarding Table A2. The first is the nonlinear relation between volatility and VaR. When volatility doubles from 0.5 to 1 the VaR also doubles, but when volatility increases from 1 to 3, the VaR increases less; it actually only approximately doubles. When volatility grows again from 5 to 15, the VaR only goes up by about approximately 10 percent. There is, therefore, a concave relation between VaR and volatility.

This can be explained on the basis of the following intuition: the worst scenarios are those combining an early call on the liability together with an increase in interest rates. The former implies an outflow that is larger than the nominal value of the liability (because the asset did not have enough time to grow to the tight value), whereas the latter decreases the value of the portfolio that the insurance company liquidates in order to redeem the liability. To clarify the relevance of the maturing of the liability, Figure A1 shows the relationship between the gap and alternative possible actual times of realization of the liability. Increasing the volatility (of the time the liability is redeemed) has no effect on the dynamics of interest rates but, as shown in Table A2, affects the difference between the effective maturity of the liability and the expected maturity.

Going back to explaining Table A2, the results of Table A1 are coherent with the nonlinear relation between volatility and VaR. Table A1 shows that increasing volatility from 0 to 0.5 moves the worst scenarios for redemption from year 8 to year 6.8 (i.e., 8 minus 1.2, the first value of Table A1) and then, for a unitary volatility, to year 5.69, with important effects on the VaR. A volatility level of 3 moves the actual maturity to 1.31, which from that point on only decreases to 0.44, 0, 26 and 0.19. In these scenarios, redemption occurs shortly after the start of the contract. In these early redemption scenarios, the interest rate effect is not particularly relevant, because there is not enough time for it to move away from the initial position and significantly affect the value of the portfolio of the insurance company.

The second interesting result is that the mean of the distribution, representing the value of the company, increases with volatility. This counterintuitive result is associated with our hypothesis of a positive slope of the term structure of interest rates. Since the positive slope of the term structure of the spot interest rates implies a positive slope also for the term structure of forward interest rates, it follows that interest rates tend to increase in our scenarios.Footnote 29 Increasing interest rates tend to be associated with capital losses for scenarios of early redemptions of the liability and with increasing reinvestment revenues for scenarios when redemption occurs after the eighth year. This is also associated with our hypothesis that the increase in the value of the liability after the eighth year is smaller than the short interest rate at which the proceeding of the sale of the portfolio is invested.

Increasing volatility affects the occurrence of extreme redemption events. However, extremely negative events, corresponding to early redemption of the liability, tend to have a less than proportional impact on value, whereas extremely positive events, corresponding to late redemptions, tend to contribute positively to the value of the firm. The difference is due to the changing nature of the investment strategy of the insurer: from the beginning to year 8 the insurer buys a zero coupon bond which is held until maturity (provided the liability does not mature unexpectedly earlier than that) but then there is a switch to a strategy of rolling over the short-term interest rate. While the costs of early selling of the bond are stable, the benefits of rolling over increasing interest rates increase.

In order to further clarify this point, Table A3 reports the average gap of three couples of symmetric (around the eighth year) gaps and shows that the higher the distance between the gaps, the larger the average gap. In other words the table is obtained by allowing for interest rate uncertainty but imposes that the liability matures respectively at 7 and 9 years, then 11 and 5 and finally 1 and 15. The results clearly show that the difference between the two gaps increases with maturity. This asymmetry is responsible for the positive relation between volatility and value.

Table A4 reports relevant percentiles of the distribution of the gap assuming a flat term structure of interest rates. The new result is connected with the negative relation between volatility and the value of the insurance company in the presence of a flat term structure. Since the flat slope of the term structure of the spot interest rates implies an equal term structure of the forward interest rates, it follows that interest rates tend to remain stable in our scenarios.Footnote 30 As in the previous case, stable interest rates tend to be associated with capital losses for scenarios of early redemptions of the liability and with positive reinvestment revenues when redemption occurs after the eighth year.

Figure A2 shows the dynamics of the short-term interest rates in both the positively sloped and the flat term structure case. To further clarify this point, Figure A3 presents a comparison between the present value of the gap for a positively sloped term structure (already reported in Figure A4) and the present value of the gap for a flat term structure. An asymmetry is visible from the figure, with long duration liabilities now offering a limited upside which is not able to offset the downside associated with early redemptions. This asymmetry is responsible for the negative relation between volatility and value.

Table A5 shows that the higher the distance between the gaps, the lower the average gap. It follows that the timing risk introduces a relationship between the shape of the term structure of the interest rate and the value and the risk profile of an insurance company. In the absence of timing risk (that is to say, in the presence of a secondary market for the liabilities), the shape of the term structure of interest rates is not relevant: since the issuer may lock its value by investing in a zero coupon bond,Footnote 31 the only relevant variable affecting the value is the spot eighth-year zero coupon rate. In the presence of timing risk, being equal to the spot eighth-year zero coupon rate, the value of the issuer varies according to the shape of the term structure of the interest rates.

Finally, we have explored the consequences of the scale of operations, modeled as an increase in the number (given a fixed overall value) of the liabilities. We have first analyzed the case of a portfolio with 25 liabilities and a positive slope of the term structure of interest rates (Table A6) and a case with 150 liabilities, always with a positive slope (Table A7). The two tables together clearly show the importance of the scale of operations. In our simulations we have assumed that the liabilities are uncorrelated. That may be realistic for a case of a true insurance liability, that is, when the liability depends on some individual-specific event like an accident or a fire. It is less realistic when the liability is associated with redemption of a financial product, as investors react to common macroeconomic and financial variables (most of all, the level of interest rates) in deciding whether to hold a specific financial product or not. For example, they all have the tendency to redeem the product if the level of interest rates rises above the minimum guaranteed rate and if the portfolio policy followed by the insurance company cannot match an increase in expected return corresponding to the increase in the short-term interest rate. In 2006–2007 this has sometimes been the case during the increase of European interest rates.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beltratti, A., Corvino, G. Why are Insurance Companies Different? The Limits of Convergence Among Financial Institutions. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 33, 363–388 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2008.13

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2008.13

, where the rate i can be interpreted as an inflation rate for a non-life insurance product or as a minimum guaranteed for a life product. This hypothesis ignores cash flow risk and is uncertain in terms of timing as the maturity is normally distributed with an expected value equal to 8 and various alternative standard deviations respectively equal to 0, 5, 1, 3, 5, 8, 15. From now on we will refer to this standard deviation as “volatility”. Alternative standard deviations will be used to show that the VaR of a company may change as a function of the volatility of its liabilities which is in turn partially endogenous. To understand this point, imagine that the liability is represented by a standard insurance product investing in a fixed income portfolio. From the point of view of the insurance company, uncertainty about the liability depends on both uncertainty of interest rates and uncertainty about redemptions. Uncertainty (and therefore volatility) depends, therefore, on endogenous variables like the ability of salespeople to stabilize net inflows;

, where the rate i can be interpreted as an inflation rate for a non-life insurance product or as a minimum guaranteed for a life product. This hypothesis ignores cash flow risk and is uncertain in terms of timing as the maturity is normally distributed with an expected value equal to 8 and various alternative standard deviations respectively equal to 0, 5, 1, 3, 5, 8, 15. From now on we will refer to this standard deviation as “volatility”. Alternative standard deviations will be used to show that the VaR of a company may change as a function of the volatility of its liabilities which is in turn partially endogenous. To understand this point, imagine that the liability is represented by a standard insurance product investing in a fixed income portfolio. From the point of view of the insurance company, uncertainty about the liability depends on both uncertainty of interest rates and uncertainty about redemptions. Uncertainty (and therefore volatility) depends, therefore, on endogenous variables like the ability of salespeople to stabilize net inflows;