Abstract

The article analyses implications for risk management in insurance arising from the current financial crisis. After a brief comparison of the insurance to the banking world, we discuss the root causes of the current financial crisis with a particular focus on risk management and incentives. Against the backdrop of this discussion, lessons are derived from an insurance risk management point of view. In particular, the article pleads for a pronounced external and forward-looking approach to supplement the traditional methodology, which tends to be more inward-looking and ultimately backward-oriented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After the demise of Lehman Brothers in the fall of 2008, the global banking system suffered a systemic meltdown in a magnitude and with a ferocity not seen since the Great Depression. The financial sector continues to struggle with the reverberations of this crisis, which has now been amplified by the fallout of the global recession. At the time of writing, a resolution is not yet in sight.

As a consequence of the financial crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that global financial institutions will have to write down more than US$ 3 trillion in the years 2007 to 2010. With US$ 2.8 trillion or 5 per cent of all loans and securities held by banks, the bulk of the writedowns will eventually be incurred by the global banking industry. A much smaller part is expected to fall on other financial market participants, such as pension funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds.

With US$ 300 billion (of which US$ 250 billion had been absorbed by October 2009), the expected writedowns of insurers are indeed comparatively small. The sector's relative underexposure, a few well-known industry participants that also conducted business activities unrelated to insurance notwithstanding, may even come as a surprise. With total assets under management of roughly US$19 trillion,Footnote 1 insurers come third behind pension funds and asset managers in the rankings of institutions managing global assets. Hence, it may be tempting to seek the difference in the performance of the banking sector and the insurance industry in the differences of their respective business models.

To be sure, there are salient differences between insurance and banking. However, they may not sufficiently explain the difference in the performance of the two industries. After all, insurers were and continue to be, by virtue of their role as large institutional investors, exposed to the fluctuations of the financial markets. And, as mentioned above, not all insurers escaped the crisis as comparatively unscathed as did the majority of the industry.

This puts the role of risk management squarely in the centre. And again, to belabour the obvious, it would be too simple to put a one-sided blame on the alleged disfunctionality of risk management in banking and contrast it to a presumed superiority of risk management in insurance. It is nevertheless worthwhile to point out that risk management in those two sectors has developed as a result of the different challenges posed by banking and insurance. Hence, it is fair to say that risk management in the two industries reflects different cultures and traditions, which over the course of the recent episode was likely to generate also different outcomes. In this perspective, the challenges emanating from the different business models and the sector-specific response of the risk management practice in insurance and banking describe an endogenous, self-reinforcing process that over time may indeed have led to the different outcomes observed in real time.

Hence, the outline of this article is as follows. We start by briefly comparing the insurance industry to the banking business in order to better understand the implications for risk management in the two industries. We then analyse, again briefly, the root causes of the current crisis. The focus in the next two chapters shall be on microeconomic causes mainly relating to incentives and risk management. This gives us an opportunity to highlight what went wrong in insurance and banking, and derive lessons for the future practice of risk management in insurance. We then summarise a few lessons learned by also referring to insights drawn up recently by the Chief Risk Officers’ Forum.Footnote 2 And we conclude by offering a few speculative comments about the development of risk management in the future.

A few salient differences

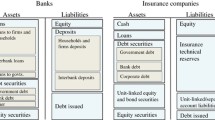

Rather than writing a voluminous treaty on the differences between insurance and banking, this article shall focus on a few salient points relating to the business model and investment function that are specific to the insurance industry and then immediately come to the conclusions for risk management.Footnote 3

The most important difference between insurance and banking stems from the inverted product cycle and the ensuing different funding structure in the insurance industry. The main point is that insurers do not rely on short-term funding to the extent of banks,Footnote 4 which are typically funded through short-term deposits or short-term borrowing. It is well known that the mismatch between short-term borrowing and long-term lending makes banking an inherently unstable business; it can give rise to runs and eventually to full-fledged systemic crises.

Insurers, in contrast, hardly run the risk of becoming illiquid.Footnote 5 Not only do they have a funding model that is different from the one prevalent in the banking industry, but policy-holders also have very little incentives to withdraw money prematurely from an insurance company for reasons other than having incurred a loss, or if they do, as it is sometimes observed in life insurance, they will incur a high cost.

The different funding model has also implications for the investment function. The primary role of insurance investment is to manage the funds generated by premium revenue and ensure that the insurer can meet expected policyholder claims at any point in the future.Footnote 6 Hence, the investment function is subordinated to the insurer's primary business, and its role differs substantially from a perhaps more colloquial view that perceives the insurer as a large hedge fund with an attached small insurance business whose sole function is to generate the flows for the investment function as many observers perceived the industry based on the behaviour and track record displayed in the late 1990s when cash-flow underwriting appeared to be the norm rather than the exception. It is clearly not a case of the tail wagging the dog, and it has meaningful implications for risk management.

Of course, the American International Group (AIG) case warrants additional qualifications. However, it might be useful to bear in mind that AIG was an insurance-based large complex financial institution (LCFI) and as such much closer to a hedge fund than to an insurer sticking more closely to the core business of “traditional” insurance. The demise of AIG as well as large banks in the United States and Europe illustrates that LCFIs generate a host of issues, including problems with respect to internal governance as well as external regulation and supervision that go well beyond the scope of this article.

The strong alignment of the investment function with the insurance business requires inter alia that the duration of assets must closely match the duration of liabilities, and it puts a high premium on the liquidity of assets. Insurers can ill afford holding assets that under stressed market conditions could turn out to be illiquid. It would force the insurer to draw on highly liquid positions with the implicit risk of illiquidity should these positions be drawn down too quickly.

The crucial takeaway from this brief and admittedly short-hand discussion of the differences between insurance and banking is that the differences have deeper implications for the management of risks in the two industries. To be sure, the management of insurance hazards is the primary challenge faced by an insurance company. But insurers learned at their own peril that neglecting the investment risk could have devastating consequences too.Footnote 7 The hard lessons made in the 2001–2003 equity market downturn led to a strengthening of both the asset-liability management (ALM) function and the role of risk management. Today, in many large insurance companies the Chief Risk Officer is a member of the management executive committee reporting not only to the company's Chief Executive Officer, but also to its Board of Directors.

The constraint on the insurer's investment function, and hopefully also improvements in the ALM, were reflected in the actual performance of the insurance sector during the recent financial crisis. By and large, insurers did not hold substantial proportions of structured investment products that during the crisis revealed themselves to be highly illiquid and excruciatingly difficult to value, and they were never forced into large-scale asset sales in order to obtain the liquidity necessary for the normal conduct of business.Footnote 8

The current performance of the insurance industry sharply contrasts with the sector's behaviour in the years 2001 to 2003, the post-mortem of the dot-com bubble. At that time, insurers had too high of a concentration of assets invested in equity securities and, in order to obtain liquidity, they were forced to sell equities in an already declining stock market. It was widely alleged that by doing so the insurance sector had actively contributed to market volatility and exacerbated the ferocity of the downturn.

It is fair to say that the insurance industry, as result of both improved ALM and the longer time horizon of insurance investments, has faired differently in the recent crisis and contributed, at least marginally, to the stability of financial markets. Rather than being a threat to the system's stability, insurers had a calming impact on the financial markets. They were not forced into financial asset fire sales and none of the large companies adhering to a pure insurance business model experienced the kind of severe financial stress that could have ended up in bankruptcy.

Of course, the best risk management and the most sophisticated ALM cannot immunize the insurance industry from the consequences of severe financial market turbulences and a long, protracted global recession. The impacts of these developments are now increasingly visible in insurers’ balance sheets and they will eventually also materialise in their income statements. However, until now, and in sharp contrast to the period 2001 to 2003, insurers as major players in the financial sector were able to face the challenges posed by the systemic meltdown in the banking industry from a position of regained strength.

The root causes of the crisis

Two years after the virulent outbreak of the subprime crisis, which triggered the cascade of events leading to the bankruptcy of Lehman, one is in the rather comfortable situation of surveying a growing body of excellent treaties dealing with the causes of the current financial crisis.Footnote 9 In the following section we shall adopt the framework developed in the 79th Annual Report of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS).Footnote 10

Fundamentally, the BIS economists distinguish two main root causes of the current crisis. The first set falls broadly into macroeconomic categories, mainly relating to growing current account imbalances across the globe. The second set is comprised of microeconomic categories, predominantly risk measurement and risk management, incentives, and regulation. We shall briefly discuss each of these categories in turn, first beginning with the macroeconomic causes of the crisis and then putting a sharper focus on the microeconomic factors in the area of risk management and relating to incentives. Regulation shall not be dealt within the confines of this article. It is a complex enough issue to warrant a separate treatise.

As far as the macroeconomic causes of the crisis are concerned, it is now almost canon to identify the main culprit in global imbalances, that is, in “the persistent and large current account deficits and surpluses resulting in capital flows from capital-poor emerging market countries to capital-rich industrial economies, especially the United States”.Footnote 11

There were and continue to be a number of factors driving these imbalances, ranging from the existence of a global saving glut to the desire of emerging market countries mainly in South-East Asia to stockpile foreign reserves as a first line of defence against sudden reversals in capital flows. Of course, one unintended consequence of this desire was the quasi-fixing of the domestic exchange rate relative to the U.S. dollar. The pegged exchange rates kept supporting export-driven growth, and they perpetuated the accumulation of both current account surpluses and foreign reserves, with the mirror image of these developments being the large current account deficits in advanced economies (mainly the United States). In other words, the system was rigged to an eventually unsustainable accumulation of global current account imbalances.

To the macroeconomic imbalances, we must add as a second driving factor: the period of low interest rates that was maintained for the first half of this decade. Again, there were many factors responsible for the environment of low interest rates, beginning with the already mentioned global saving imbalances that fostered a continuous flow of capital to the United States and ending with the conscious policy choice of the U.S. Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low for too long a period to fight the spectre of deflation. The unintended consequences of low interest rates resulted in an unprecedented credit boom in the U.S. and elsewhere, but also in an increasingly frantic search for yield by investors not satisfied with the prevailing low returns on plain vanilla assets.

In passing, one cannot refrain from pointing out that the current aggressive fiscal and monetary policy mix has not reduced any of these macroeconomic imbalances. On the contrary, interest rates continue to be low, emerging market countries in South-East Asia keep savings high, their exchange rates are still pegged to the U.S. dollar, and the strong fiscal impulse pursued by most industrialised countries will foster a rapid accumulation of public debt.

It is being said that the reduction in macroeconomic imbalances, which is necessary to support sustainable growth of the global economy, will be the result of an exit strategy. However, a strategy that would credibly describe the eventual retraction from current high monetary and fiscal stimulus has yet to be formulated and, as many may be concerned, is unlikely to emerge in time and with forceful enough actions. Likewise, there is no financial architecture in place that could oversee the necessary adjustments in advanced and emerging market economies. Consequently, the next global financial crisis appears to be programmed, and one can only speculate about which event may trigger the collapse in the future.

Microeconomic drivers of risk management failures

More interesting for the purpose of this article are the microeconomic root causes of the financial crisis. According to the BIS framework, they relate to risk measurement and risk management, incentives and regulation.Footnote 12 In the following section, we shall focus first on the areas dealing with risk management and then turn to the role of incentives.

Risk is, of course, inherent in any entrepreneurial endeavour. Risk and reward are the proverbial Siamese twins, and a corporation is successful only when it is capable of well managing a portfolio of risks and their associated rewards.Footnote 13 We can deduct from this that risk management is not only a formal process, but fundamental to business conduct. In fact, risk management in this broader sense is essential to achieve a company's strategic, operational and financial objectives.

So what went wrong?

If risk is intimately related to return, and if risk management is such a core function in the modern company, how come so many financial institutions were found wanting? In two important publications, René M. Stulz has recently offered a systematic treaty identifying six perennial mistakes in risk management.Footnote 14 Footnote 15 They include (1) an over-reliance on historical data, (2) an unfortunate focus on narrow measures, the fact that (3) known risks or (4) concealed risks are often overlooked, (5) governance problems particularly also related to communication, and (6) the inability to manage in real time.

This is indeed a long list. In essence, however, it boils down to two broad categories of mistakes relating to:

-

a lack of awareness of the constantly changing nature of risk and of the grey zone that separates risk from uncertainty;Footnote 16 and

-

the failure to act in a timely and decisive manner on the analytical insights (or awareness) gained through the normal practice of risk management.

In the interest of brevity, we shall focus on these two broad categories. It will become readily apparent that over-reliance on historical data and a focus on narrow risk measures (as identified by Stulz) fall into the two categories. The argument with respect to uncertainty will be taken up again in the concluding section, where we offer thoughts on the future development of risk management.

The measuring, pricing and managing of risk is art and science at the same time. In the average insurance scheme, where risks have a high frequency and low severity— in motor insurance, for example—standard statistical tools can be brought to bear. We can typically rely on long data histories, and the data are normally distributed with thin tails. Hence, the expected losses are pretty much centred on the mean and highly predictable; the likelihood of large losses occurring is very small indeed.

However, the world is entirely different when it comes to the losses observed in the recent financial crisis. Such losses occur at infrequent intervals, and when they occur, they tend to be very large, often with systemic consequences. Therefore, extrapolating from the past to the present will be misleading, and even more so because the events are not normally distributed. There is a paucity of data, and the statistician has at best a hunch that the tails of the distribution are not thin, but rather fat.

The problem described above was exacerbated by the proliferation of new financial instruments that were developed over the past 15 years. By definition, there was no history to statistically assess their riskiness. Moreover, the pooling of arguably low-quality loans and their subsequent slicing and dicing through the process of securitization into a continuum of low- to high-quality securities backed by these pools was not made on entirely sound methodological foundations.

In many areas of finance, the underlying working assumption is that events are normally distributed; it keeps the models simple and easy to manipulate, but it is far from reality. Events in complex financial systems are not normally distributed, and the tails of the loss function are not thin, but fat. This has been painfully illustrated by the failures of the widely used Value-at-Risk (VaR) models. VaR is the largest loss a firm expects to suffer at a given confidence level and over a certain time horizon. Unfortunately, VaR does not give any information about the loss distribution. Further shortcomings are that the future is not necessarily an extension of the past, that correlations are not stationary and that the time horizons used to calculate VaR are too short.Footnote 17

Could it be that the banking industry was too complacent when measuring and assessing risks? And what do insurers do when faced with similar problems?

Obviously, the problems faced by the banking industry were not trivial. Had they been easily identifiable and readily avoidable, they would have been identified and avoided. However, one could also claim that insurers, in light of their experience with extreme events, might have approached the challenges differently. In the following section, this idea will be developed with references to the insurance industry's approach to large catastrophe risks and emerging risks.

First, it is important to realise that insurers, when it comes to large natural catastrophes, go out of their way to analyse exposures over very long time horizons. Reinsurers typically work with models to protect against one in 500 year events—the Great California Earthquake, perhaps – and it is not uncommon to see references to 1 in 1,000 year or 1 in 2,000 year events. Insurers routinely put up capital to protect against low frequency, high severity events.

Second, over time insurers have pushed the envelope of the insurable. Today, customers can obtain cover against risks that were deemed uninsurable perhaps only a decade ago. The most recent example of innovation in insurance extends to the offer of cover against the risk of interruptions in supply chains and the risks of climate change.

Advances in insurability were and continue to be made often despite a paucity of long data histories. Insurers have learned to work themselves around such problems. There is an arsenal of tools available, from Monte Carlo simulations to Extreme Value TheoryFootnote 18 that enables the modelling of extreme events. Not using them and relying instead on models with known weaknesses (such as the normal distribution, an assumption underlying most of the financial products sold in the recent decade) must indeed contribute to failures in the assessment and management of risk.

This being said, it should be added that models—no matter how advanced or sophisticated—cannot be the end and all of risk management. Historical data are important, and Monte Carlo simulations can be most revealing. But in the end, risk management must also apply common sense. It always pays to include several dimensions of risk and complement conventional risk measurements with stress testing based on meaningful scenarios and expected shortfalls.Footnote 19

Finally, and to conclude this section, here is a word on the failure to rely on too narrow risk measures. This is particularly relevant in the context of the current systemic crisis, which has made abundantly clear that a risk management conducted in silos and neglecting the interconnectedness of risks is bound to fail.

While it is, for obvious reasons, fiendishly difficult to account for the possible universe of all risk interconnections, it is neither a futile nor an impossible task. Again, insurers have broadened their approach and developed a methodology that accounts for systemic impacts. In the following this is illustrated with the example of exposure and accumulation management in hurricane-prone regions.

Exposures are simple enough to define, quantify, and manage. As a general rule, insurers will seek to limit their total number of risks in a particular catastrophe-prone territory. The rationale is familiar to anyone who was taught as a first principle of portfolio management not to put all eggs in one basket. The implication for insurers is that they can have too much market share, if the share is disproportionately located in too small a catastrophe-prone territory. That is why underwriters are given limits and why it is not unusual for insurers to withdraw from markets if they cannot obtain rates commensurate with the risk exposure.

However, it is not the exposure management part of the equation that has the broader application for the current crisis. It is rather the second part of the insurance calculus, the treatment of the accumulation exposure that has implications for risk management in other financial industries. The definition is perhaps more complex, but in a bit of an over-simplification it suffices to say that accumulation is the product of exposures multiplied by the maximum possible loss per exposure (e.g., the cost to re-build the total number of hurricane-exposed houses if every house is a total loss).

The results of proper accumulation management were revealed after hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008, when a number of carriers were shown to have substantially smaller total payouts than their market share in the hurricane-affected regions would have implied. It was a direct result of having carefully managed the spacing of exposures and monitored the accumulated risk in a disciplined manner.

It is easy to see what a better exposure and accumulation management could have done for the banking industry. It appears, to use the insurance terminology, that analysts in banks and rating agencies stopped at the exposure analysis without paying much attention to accumulations.

One can illustrate this with a reference to asset-backed securities (ABS) built on subprime mortgages. While solely focusing on exposures, analysts were quick to point out that even if 10 per cent of subprime homeowners failed to repay the loans, the remaining 90 per cent would still honour their obligations. They concluded that although some subordinated tranches of the ABS might suffer losses, the overall outcome would still be acceptable, because the higher-rated ABS tranches would continue to be serviced timely and in full.

However, analysts had failed to account for the impact of accumulation, which was worse than the pure exposure impact. The collapse in the subprime housing segment and eventually in the entire U.S. housing market was the equivalent of hurricanes Andrew and Katrina combined. The risks emanating from the real estate market were not isolated and they kept proliferating through all other structured products that referenced the housing market. After having multiplied the exposures by the accumulated total loss on tranche after tranche of these securities, the systemic market meltdown was complete. It was based on a breakdown in risk management that had failed to account for accumulation risk and to truly evaluate worst-case scenarios.

The role of incentives

This brings us to the second major microeconomic root cause of the crisis, to the role of incentives. Again, the contrast between insurance and banking can illustrate what is at stake and offer lessons for the future of risk management in the financial industry.

One key word in this context is moral hazard or the transfer of risk without properly accounting for the risks underlying the transaction. It is important to see how insurance has dealt with the intricacies posed by the challenge of moral hazard, and we shall illustrate this with the different approaches taken to the process of securitization in insurance and banking.Footnote 20

To begin with, it is necessary to recognise the differences arising from the securitization of assets (such as mortgages or car loans) and the securitization of liabilities (catastrophe risk or a book of motor insurance). Whereas ABS are the work horse of securitization in the banking industry, the securitization of liabilities is associated with the insurance industry only.

The difference in the nature of asset and liability securitization leads to a number of observations critical for the purpose of this article.

-

The strong correlation among bank assets provides an incentive for the banking industry to transfer some or all of these risks to the capital markets. Securitization is one way for banks to improve the diversification of their asset portfolio and to reduce the overall risk inherent in their portfolios. The case is not as clear-cut in the insurance industry. Insurers with large portfolios tend to benefit already from portfolio diversification, without having to transfer some of the risks to the market. In fact, for insurers, risk transfer may not provide meaningful incremental benefits at all.

-

As a consequence of these incentives, banks found it beneficial to develop an “originate-to-distribute” (OTD) business model by creating the securitized instruments that allowed them to transfer asset risks to the capital market. But the change in the business model had a number of far-reaching consequences. In particular, it:

-

completely separated the origination of risk from the holding of risk; and it

-

introduced new and, as it turned out, fatal governance issues; because the distributors of risk had divorced themselves from the origination of risk, they no longer had “skin in the game”.

-

In short, the proliferation of the OTD business model created what economists call a principal-agent-problem or agency problem that tends to be associated with the prevalence of incomplete and asymmetric information. As a consequence, underwriting standards slipped and the due diligence of assets related to subprime mortgages and corresponding derivatives was at best inadequately performed. Risk assessment became deficient, which in turn led to an underpricing of risk and investors ended up with an ultimately unsustainable accumulation of risky assets.

Marian BellFootnote 21 and Heijo HauserFootnote 22 have described the events in the build-up to the current financial crisis in detail and we refer the interested readers to their studies. For the purpose of this article it is important to underscore that the agency dilemma sketched above is well contained with insurance-linked securitization.

Indeed, what differentiates catastrophe (CAT) bonds from ABS vehicles is that insurers are typically transferring peak risks only. This implies that insurers tend to hold a considerable fraction of the catastrophe risk themselves, and because they continue to have “skin in the game”, they not only have an incentive to maintain high underwriting standards, but also sophisticated standards for the monitoring of risks.

In other words, buyers of CAT bonds not only purchase an asset for investment, but implicitly participate also in the underwriting that went into the creation of the asset. And with that participation comes an implicit portion of the risk management culture that shaped the insurer's strategy, its approach to the business and its guidance to the underwriters. In that sense, an insurer's risk management capability is inextricably linked to the securitization of insurance liabilities.

On the backdrop of this discussion it is encouraging to see that recent proposals to strengthen the financial system include such minimum requirements for retained risk by the risk's originator.Footnote 23 For our taste, the required “skin in the game” or retained risk proportions, our could even be higher than the 5 per cent currently discussed in the wake of the U.S. Treasury White Paper. Perhaps, a minimum of 25 per cent of each loan to be retained by the originator would enable the remaining 75 per cent to be securitized more safely. One could even imagine that collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) with higher retained ratios (50 per cent, or higher) would be worthy of higher ratings from the rating agencies. And, to drive the speculation even further, with such a Retained Risk Rating model, one would no longer have to rely on rating agencies. After all, the insurance experience teaches us that with so much skin in the game, or such a high proportion of risk retained, loans that are less likely to be re-paid would not be made in the first place.

Lessons learned

More than two years into the crisis one is in the comfortable position—although for rather uncomfortable reasons—to survey a number of reform blueprints and proposals to strengthen risk management. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) was one of the first out of the gate with comprehensive recommendations for best practices in the financial industry.Footnote 24 And leading up to the April G-20 Summit, and then again in response to that event. The Geneva Association published a series of important documents articulating the salient differences between insurance and banking and deriving implications for a constructive financial sector regulation that is mindful of them.Footnote 25 Footnote 26 Indeed, it would be counterproductive if an industry that continued to operate normally in the face of the most severe financial crisis in recent memory were to be penalized by a regulatory framework that failed to recognise that insurers had not been the source of the systemic crisis. On the contrary, as stated before, they weathered the crisis comparatively unscathed and, as The Geneva Association underscored, due to their role as holders of assets on behalf of customers and policy-holders, their impact on the financial system was stabilising.

Recently, the CRO ForumFootnote 27 has issued a set of responses directed more specifically to the practice of risk management in insurance companies. One should indeed expect that the IIF recommendations and the responses articulated by The Geneva Association and the CRO Forum will eventually define a core of best practices to be emulated over time by all financial institutions. In the following, we shall highlight the recommendations made by the CRO Forum on the backdrop of the findings developed in this article. Two lessons relate directly to our points, and we shall look at them in turn.

-

Lesson 1: Risk governance and culture must be integrated throughout the whole organisation. The crisis has revealed that excessive risk-taking may occur if risk management is fragmented and if too low a priority has been assigned to it.Footnote 28 In this article we have shown that risk management must extend to the risks on the liability and asset sides of the balance sheet; it must be comprehensive, and a careful control of exposure and accumulation risk is indispensable. Over recent years, insurance companies have made big strides, and they should be encouraged—also by regulatorsFootnote 29 —to continue on this path in the future. It has, of course, far-reaching implications for risk governance under the auspices of the Board of Directors and, as LehmannFootnote 30 pointed out, for the function of the Chief Risk Officer. And finally, good risk governance not only includes a clearly articulated and monitored overall risk tolerance, but also incentives that extend not only to risk-adjusted compensation schemes that can be sustained over the long term, but also to risk-based underwriting standards.

-

Lesson 2: Risk modelling must rely on an eclectic mix of risk methodologies and include qualitative judgments. There can be no doubt that the current crisis was preceded by rapid advances in quantitative finance and sophisticated modelling efforts. Alas, too many models were focused too narrowly, and their weaknesses never made it to the board room. But model output must be carefully reviewed, model alternatives should be run, and a heavy dose of common sense applied.Footnote 31 Expert judgment, particularly in the board room, is indispensable. In the past insurers have demonstrated competent approaches to both the modelling of extreme risks (such as natural catastrophes) and the inclusion of emerging risks. They were not necessarily catastrophe-proof as the costly fallout of the 2005 hurricane season in the United States painfully demonstrated. But most insurers appear to have learned their lessons, and they are moving forward with improved models and a better understanding of the complexities bearing on hurricane modelling.

In addition to the two lessons mirroring the key points of this article, the CRO Forum also makes recommendations on the management of liquidity risk and the need for improved risk valuation.

-

Lesson 3: Liquidity risk management must prepare for the unexpected. Although liquidity risk is, for reasons given above, not a primary concern for insurers, it can be rather disruptive. Hence, liquidity planning should take into account normal and contingent liquidity needs, as well as disruptions to liquidity due to adverse market developments.Footnote 32 There appears to be some catching up to do by insurers as liquidity risk management has not received sufficient attention in the past.

-

Lesson 4: Risk valuation and communication must improve. It is self-evident that an accurate risk valuation is essential for the consistent and objective measurement of risk. However, the crisis has shown that valuation becomes difficult when certain markets close down. Moreover, valuation to market is a particular challenge for insurers, because insurance liabilities are typically not traded in markets. Again, the CRO ForumFootnote 33 has proposed a sensible solution for dealing with these challenges.

Risk management going forward

As said previously, one should hope for the insurance industry to adopt expeditiously the lessons drawn by bodies such as The Geneva Association, the IIF or the CRO Forum. They describe a set of best practices whose implementation over time will be indispensable.

However, many of these best practices are concerned with technical aspects of risk management and risk governance. Adherence to them is a necessary condition for success, but adherence alone may not be a sufficient one. Risk management must go beyond conventional approaches and push the boundaries of our current thinking.

What differentiates the current financial crisis from other episodes is its systemic character. The financial crises in the late 1980s and early 1990s, such as the collapse of the U.S. Savings & Loan (S&L) industry and the real estate-related banking crises in Japan, Switzerland and the Nordic countries, were either limited to one sector (the S&L crisis in the U.S.) or to individual countries. Large-scale systemic crises do not occur frequently. In fact, the last one with global ramifications happened 80 years ago. However, when they occur, they are associated with devastating losses.

Clearly, risk management failed to account for the systemic threat in both the private sector and on the regulatory level. It failed for the simple reason that the whole is often larger than the sum of its parts. In other words, risk management has fallen into an aggregation trap. What during the bubble period was individually rational and sustainable, was in effect collectively irrational and no longer sustainable.

Without referring explicitly to collective irrationality, Raghuram RajanFootnote 34 has argued persuasively that financial innovation based on the extrapolation of rational economic models can appear to stabilise the financial system for a long time and that complex financial systems appear to be robust in the face of many small deviations from the equilibrium. But there comes a point when the cumulative impact of many small deviations can no longer be contained and when the rationality assumption no longer holds. What was rational during the boom becomes evidently irrational after a certain threshold has been reached. The bubble bursts, and the crisis is lethal.

In hindsight it is easy to see that risk management was almost predestined to fall in the aggregation trap. Over the years, sophisticated models were developed to identify and manage the risks residing on the balance sheets of banks and insurers alike. They gave a fairly accurate sense of balance sheet risks over a long period of time. However, the models were, by construction, concerned mainly with risks relating to the individual corporation, and they presented an internal and ultimately backward-looking view. Furthermore, the prevailing risk modelling methodologies worked reliably only for comparatively small deviations from the equilibrium. They were not equipped to deal with the discrete jumps caused by systemic disruptions.

Of course, that is not a realistic picture of the world. Low frequency, high severity events, such as today's financial crisis, do occur from time to time. They may be more prevalent in insurance in the form of natural and man-made catastrophes, but banks should have nevertheless raised their awareness prior to the crisis. The likelihood of low frequency, high severity events requires for risk management to augment the internal and backward-looking approach refined in the past with an external and forward-looking perspective. The analysis must include risks that are not necessarily germane to the corporation or the sector only, but could also play a role in a systemic context. Applied to the insurance industry, it follows immediately that the likelihood of a systemic banking crisis and the subsequent financial meltdown must be systematically hard-wired in the risk management calculus.Footnote 35

Obviously, the future is fraught with uncertainty, or “unknown unknowns” in the immortal words of a former American Secretary of Defense, and it would be preposterous to predict the unpredictable. But an approach to risk management that is premised on the insight that uncertainty exists, developments occasionally assume irrational features, and events unfold in discrete jumps, may be better equipped to cope with the challenges brought on by the real world. It might also be a risk management that is more humble, because it would be aware of the limits to rational modelling and what can be said on the basis of scientific arguments. There are times and occasions when even science must remain silent.

This entails, at least to some extent, a break with tradition that will ultimately go beyond risk management and should include many neighbouring and supporting disciplines. In a seminal collection of essays, Akerlof and ShillerFootnote 36 have sketched the contours of such a break with tradition for the field of macroeconomics. They propose to suspend an analytical framework that allows for only small deviations from the equilibrium and that is built on rational behaviour.

While acknowledging that standard general equilibrium analysis can generate powerful results that are valid most of the time, they accuse traditional model builders of failing to account for “non-economic and irrational behaviour”. According to Akerlof and Shiller, such models ignore the “animal spirits”, which Keynes had so eloquently identified as the driving force of the capitalistic market system. But “insofar as animal spirits exist in the everyday economy, a description of how the economy really works must consider those animal spirits”.Footnote 37

And that is precisely the challenge for risk management in banking and insurance going forward. It must become aware of the animal spirits driving the real economy. It must factor in non-economic and, at times, irrational behaviour. It must recognise that developments are not always best approximated by continuous models, because the real world moves forward in discrete jumps. And it must broaden the horizon to include an array of risks and their potential for systemic repercussions.

In short, our proposition is that risk management should endeavour to widen its traditional internally focused and ultimately backward-looking approach to become more externally oriented and forward-looking. It requires new thinking and the development and implementation of new tools. At the same time, it may also introduce a sense of humility by pointing to the limits of risk management. In a world driven by animal spirits that is subject to discrete and at times disruptive developments risk management cannot prevent failures. However, its goal should be to enhance the awareness of potentially adverse outcomes and endeavour to make insurance business strategies more resilient. And that is an exciting agenda to keep working on.

Conclusions

The article has analysed the implications for the practice of risk management in insurance arising from the current financial crisis. After a brief comparison between the insurance and the banking world, the root causes of the current financial crisis were analysed with a particular focus on risk management and incentives. Against the backdrop of this discussion, lessons were derived from an insurance risk management point of view.

Our conclusion is in particular for a pronounced external and forward-looking approach to risk management to supplement the traditional methodology, which tends to be more inward-looking and ultimately backward-oriented. It also recognises that developments are not always best approximated by continuous models, because the real world moves forward in discrete jumps. And it may instil a new sense of humility by pointing to the limits of risk management. In a world driven by animal spirits that is subject to discrete and at time disruptive developments, risk management cannot prevent failures. However, its goal should be to enhance the awareness of potentially adverse outcomes and endeavour to make insurance business strategies more resilient.

Notes

Much of this has also been discussed succinctly by Liedtke (2008).

9 Citi (2008).

See for example chapter 1 in the joint write-up by the faculty of the New York University Stern School of Business in Acharya and Richardson (2009).

Bank of International Settlements (2009), pp. 7–10.

Frank H. Knight was the first to explore systematically the difference between risk and uncertainty and its implication for decision theory. See Knight (2006).

See for example the contribution on extreme events modelling by Embrechts et al. (2008).

The following draws from Lehmann (2009c).

See U.S. Department of the Treasury (2009, p. 44).

Liedtke (2009) provides a neat summary of some regulatory implications.

See for example the March 30 letter to the Finance Ministers of the G-20 Governments; The Geneva Association (2009).

Akerlof and Shiller (2009, p. 5).

References

V. Acharya, and M. Richardson, (eds.) (2009) Restoring Financial Stability: How to Repair a Failed System, New York: Wiley.

Akerlof, G.A. and Shiller, R.J. (2009) Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters For Global Capitalism, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bank of International Settlements (2009) 79th Annual report – 1 April 2008 – 31 March 2009, (June 29).

Bell, M. (2008) The 2007–08 financial crisis – An insurance industry perspective, Paper for the International Advisory Council, (April).

Citi (2008) ‘Citigroup Global Markets’, Asset Gearing Update, Under Cover – Implementing elements for Solvency II. Issue 304 (April 16).

CRO Forum (2008a) Market Value of Liabilities for Insurance Firms, Implementing elements for Solvency II (July).

CRO Forum (2008b) Liquidity Risk Management–Best Risk Management Practices, (October).

CRO Forum (2009a) Internal Model Admissibility–Principles and Criteria for Internal Models, (April).

CRO Forum (2009b) Insurance Risk Management Response to the Financial Crisis, (April).

Embrechts, P., Küppelberg, C. and Mikosch, T. (2008) Modelling Extremal Events: for Insurance and Finance, New York: Springer.

Fürer, G. and Haegeli, J. (2009) Lessons from the Credit Crisis: An Investment Practitioner's Point of View, Paper presented at the 11th Meeting of The Geneva Association's Amsterdam Circle of Chief Economists, Amsterdam.

Hauser, H. (2008) ‘Subprimekrise—nur ein Bankenproblem?’ Versicherungswirtschaft, 1 March 2008, 5: 351–363. Jahrgang.

Hofmann, D.M. (2008) ‘A risk management approach to financial crisis prevention’, Insurance and Finance No. 3, April 2008, The Geneva Association.

Hofmann, D.M. (2009) ‘RISKsa Magazine’, May 2009, pp. 20–22.

Hofmann, D.M. and Lehmann, A.P. (2008) ‘Dedicated insurers are not a systemic risk An assessment after the first year of the global credit crisis’, Insurance Economics No. 59, January 2009, The Geneva Association.

Institute of International Finance (2008) Final report of the IIF committee on market best practices: Principles of conduct and best practice recommendations, financial services industry response to the market turmoil of 2007–2008, (July), Worlde Economic and Financial Surveys, pp. 9–13; 31–48.

International Monetary Fund (2009) Global financial stability report–Navigating the financial challenges ahead, October, World Economic and Financial Surveys.

Knight, F.H. (2006) Risk, Uncertainty and Profit, Dover Books on History, Political and Social Science, Dover.

Lehmann, A.P. (2008) ‘Riskantes Risikomanagement!?’, in B. Strebel-Aerni (ed) Standards für nachhaltige Finanzmärkte, Zürich, Basel, Genf: Schulthess, pp. 109–127.

Lehmann, A.P. (2009a) Enterprise risk management—key elements for a new risk culture, Presentation at the Peak Performance Meeting, 23 January 2009.

Lehmann, A.P. (2009b) Ganzheitliche Risikosicht hat gefehlt, Handelszeitung, 10 June 2009.

Lehmann, A.P. (2009c) ‘A perspective from a large global primary insurer’, in D. Toplek (ed) Convergence of Capital and Insurance Markets, Vol. 49, St Gallen: I-VW HSG Series, pp. 99–112.

Liedtke, P. (2008) Credit crisis and Insurance—A Comment on the Role of the Industry, Insurance and Finance SC 1, The Geneva Association, 14 November 2008.

Liedtke, P. (2009) On Risk, Rescue and Hazards—The Global Crisis, Insurance and Finance No. 4, The Geneva Association, February 2009.

McKinsey Global Institute (2008) The new power brokers: Gaining clout in turbulent markets, July.

Rajan, R.G. (2005) ‘Has financial development made the world riskier?’, The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Singh, R. and Lehmann, A.P. (2009) Insurance regulation—Lessons for group supervision to be learned from turmoil, Global Risk Regulator, May 2009.

Stulz, R.M. (2008) ‘Risk management failures: What are they and when do they happen?’ Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 20 (4): 39–48.

Stulz, R.M. (2009) ‘6 ways companies mismanage risk’, Harvard Business Review, March 2009, 87: 86–94.

The Geneva Association (2008) 10 Frequently Asked Questions on the Credit Crisis and Insurance, Insurance and Finance SC 2, The Geneva Association, 19 November, 2008.

The Geneva Association (2009) ‘Executive Summary—The Geneva Association's letter to the Finance Ministers of the G-20 Governments’, at http://www.genevaassociation.org/.

U.S. Department of the Treasury (2009) Financial regulatory reform: A new foundation: Rebuilding financial supervision and regulation, June.

Zurich Financial Services (2008) Dealing with the unexpected—Lessonsfor risk managers from the credit crisis, A Zurich Report in Applied Risk Management (September).

Zurich Financial Services (2009) Investment management—a creator of value in an insurance company, (March) Second Edition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

For valuable inputs, the author is indebted to Matthias Frieden, Dr Yvonne Helble, Patrick Liedtke, Angel Serna, and two anonymous referees.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lehmann, A., Hofmann, D. Lessons Learned from the Financial Crisis for Risk Management: Contrasting Developments in Insurance and Banking. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 35, 63–78 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2009.38

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2009.38