Abstract

Insurance is all about risk management and risk mitigation. A significant component of this risk equation is an ability to manage the variability of weather events. Climate modelling has shown that it only takes small changes in the mean climate to generate large changes in extreme weather. This has profound implications for the insurance industry, because a less-predictable climate impacts the industry's capacity to accurately calculate and price products. The insurance industry's response to climate change will determine the shape of the industry for decades to come. However, insurance companies acting alone, or even collectively, will have only limited impact in achieving success over the long term. This paper outlines a multi-level approach required by the insurance industry to make a real and lasting difference, including engaging governments; assisting and educating communities to be more aware and resilient; incentivising customers through advocacy, product innovation and appropriate product offerings; and leading by example and providing employees with the education and tools to facilitate action both at work and at home.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The insurance industry needs to act on multiple levels if it is to address climate change effectively. This means not only being active participants in the global debate, but also seeking to engage all levels of the government, assisting and educating communities to be more aware and resilient, incentivising customers to take more environmentally-friendly options and leading by example while facilitating employee action.

Insurance is all about risk and, more specifically, risk management and risk mitigation. A significant component of this risk equation is an ability to manage the variability of weather events. Understanding the way changes in climate may affect weather patterns is vital because a less-predictable climate impacts the insurance industry's capacity to accurately calculate and price products.

The insurance industry must remain at the forefront of raising awareness and driving action on climate change because the way we respond to climate change will determine the shape of our industry for decades to come.

Insurance companies acting alone, or even collectively, will have only limited impact in achieving success over the long term. There needs to be a multi-level approach that involves government, community groups, customers and employees to make a real and lasting difference.

This paper begins with a brief discussion about the reality of climate change, and why it is therefore core business for the insurance industry, and how Australia is expected to be one of the countries most affected by climate change. These introductory sections highlight the need for action. The paper then outlines a multi-level approach that includes:

-

engaging government;

-

assisting and educating communities to be more aware and resilient;

-

incentivising customers through advocacy, product innovation and appropriate product offerings; and

-

leading by example and providing employees with the education and tools to facilitate action both at work and at home.

Climate change is real

There is a consensus of scientific opinion that climate change is underway. What is less clear is how the changes in the broad climate will affect either the frequency or the financial impact of severe weather at a regional level now or, more importantly, in the future. However, climate modelling has shown that it only takes small changes in the mean climate to generate large changes in extreme weather and this will have profound implications for the insurance industry.

In Australia, climate change-induced alterations to temperature, humidity and wind, together with changes to regional weather patterns, have resulted in a warming trend across the continent. This is predicted to increase in the coming decades and therefore to potentially increase the danger of bushfire, more severe and frequent storms, and other weather events such as dust storms.

Some argue that the trend of more severe and frequent weather events has already begun. In its most recent annual Natural Catastrophe Review, Munich Re reported that 2008 was the third most expensive natural catastrophe year on record for the insurance industry on the basis of figures adjusted for inflation.Footnote 1 Insured losses in 2008 rose to US$45 billion, around 50 per cent higher than in the previous year.Footnote 2

It may be premature to attribute such statistics entirely to climate change. For example, a range of societal factors—such as the fact that we have bigger and more expensive houses and cars—are also contributing to the increase in insured losses.

Nevertheless, there is no dispute that a major consequence of climate change is to make the understanding of weather-related risk more complex. The public benefit of insurance is that insurers seek to understand, calculate, price and spread risk, so that the overall risk to the community is reduced. The ability to price risk appropriately is therefore critical.

One of the most important components of any risk calculation is historical claims information. The uncertain effects of climate change means that historical claims experiences can no longer be directly applied to current and future weather risk pricing—particularly extreme weather events. This has the potential to affect the long-term sustainability of the insurance industry and therefore the availability of insurance to consumers.Footnote 3

To put the potential impacts into some context, there have been a number of recent events in Australia that have caused significant loss and cost to communities and insurers. The February 2009 Victorian Bushfires resulted in losses of just over A$1 billion and the Brisbane storms in November 2008 resulted in A$309 million of loss. It is important to note that the total economic losses from these events would be much higher than the insured losses. The economic losses from natural disasters are not calculated and can be difficult to determine. However, a Bureau of Transport report on “Economic costs of natural disasters in Australia” estimated that total economic losses were three times greater than insurance costs for hailstorms and bushfires, five times greater for tropical cyclones and ten times greater for floods.Footnote 4 Even if these estimates contain margins for error, it is clear that economic losses are likely to be considerably greater than insured losses.

The implementation of global mitigation strategies could reduce the amount of global warming that will occur in the future; however, the momentum in the climate system caused by past and present behaviour dictates ongoing changes in our future climate is inevitable.

It is therefore critical that we seek to better understand the impact of climate change, and for all stakeholders to work together to mitigate and adapt to its effects.

The impact of climate change on Australia

Australia is likely to be one of the countries most affected by climate change. This is a sobering thought when one considers that about 95 per cent of the most costly natural disasters in Australia, in terms of property insurance losses, are weather related. Australia already experiences tropical cyclones, severe storms, hailstorms, bushfires and flood. All these extreme weather events are predicted to increase in frequency and/or intensity as a consequence of climate change.

Many aspects of Australian society are vulnerable to the increased threat posed by climate change. They are as follows:

-

From a demographic perspective, more than 80 per cent of Australia's population resides within 50 kilometres of the coast and about one quarter of Australia's population growth occurs within three kilometres of the coastline. These communities are particularly exposed to some of the most damaging extreme weather events, such as tropical cyclones, storm surges, hailstorms and coastal river flooding.

-

From an environmental perspective, Australia is home to 16 World Heritage-listed ecosystems and areas that have properties of uniqueness and international ecological importance. Many of these World Heritage-listed ecosystems are in significant danger of extinction as a result of climate change. These include rainforests and tropical wetlands, the coral reefs on the Great Barrier Reef and the Alpine Region of south eastern Australia.

-

From an economic perspective, the Australian tourism industry and the agricultural sector, which contribute about 8 per cent of GDP, are also extremely vulnerable to the threat of climate change.

All these factors confirm that it is critical for Australia to better understand climate change and its associated risks.

Climate change, however, is very much a global issue and Australian insurers have sponsored research at various scientific institutions that study how the climate is changing globally, with a particular focus on tropical cyclones and hailstorms.

IAG also has its own dedicated Natural Hazards Research Team that ensures our risk pricing is appropriate for the risk exposure that exists now and into the near future. The Natural Hazards Research Team has identified the key weather elements that produce extensive damage and disruption to communities and is seeking ways to better quantify their future impact through accurately identifying current risks of potentially devastating events such as tropical cyclones and hailstorms.

Tropical cyclones

In conjunction with climate scientists, weather analysts from within the Natural Hazards Research Team have undertaken climate change research in relation to future tropical cyclone frequencies, intensities and impacts. Preliminary research shows that there is expected to be a small but steady increase in the frequency of tropical cyclones over the Australian region, commensurate with the increase in intense tropical cyclone activity in various regions shown in international studies.Footnote 5 The tropical cyclone season is also expected to be extended by more than two weeks. In addition, the generation and propagation of tropical cyclones is expected to extend a further two degrees of latitude south. These forecasts have serious implications for the heavily populated areas of coastal south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Australia's Cyclone Testing Station was established over 30 years ago, following Cyclone Tracy's devastating impact on the Northern Territory capital of Darwin in 1974. The work undertaken by the Station has been of paramount importance in developing building codes and standards that, through improvement in the quality of construction, ensure that the region will never see a repeat of the extent of the damage caused by Cyclone Tracy. The knowledge that these codes and standards are based on sound risk management principles allows insurance companies to limit insurance premiums without exposing themselves to unacceptable risk.

The Cyclone Testing Station also conducted extensive investigations following Cyclone Larry in 2006 and the Brisbane storms in November 2008. The research found, once again, that a small oversight in the design or construction process can lead to a disproportionate amount of damage should a cyclone or high wind event occur.

Hailstorms

Again in conjunction with climate scientists, weather analysts from within the Natural Hazards Research Team have also undertaken research into the potential changes to hailstorms, particularly across the heavily populated Greater Sydney region. Hail damage has been involved in approximately half of Australia's top 20 property insurance losses since 1967. The research suggests that a hailstorm with hail stones greater than 10 centimetres in diameter, such as the Sydney storm of 1999, could become twice as frequent by 2050. This has consequences not only for insurers, but also for personal safety, disaster relief planning and, as a result of business interruption, the national economy.

A multi-level response

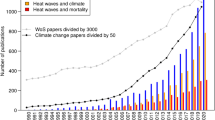

The challenge, therefore, is significant and is of such scope and complexity that it clearly requires a response on various levels. While a meaningful response will require action across the community, it is clear that insurers can play a positive role in driving this process—and there is growing evidence of a range of initiatives already underway, with a recent paper noting a 50 per cent year-on-year increase in activity.Footnote 6

Engaging the government

A multi-level approach to climate change clearly must involve the various levels of the government and there are many ways industry and the government can productively work together.Footnote 7 For example, the government plays a crucial role in providing a comprehensive and clearly defined regulatory framework that both supports the mitigation of climate change impacts and promotes community resilience to risk and facilitates more affordable premiums and more predictable claims costs. This role includes encouraging and regulating risk-appropriate development of the built environment and providing an appropriate emergency services framework.

The insurance industry can make a valuable contribution to this process by participating actively in the policy formulation process and ensuring that governments are fully informed of the risks posed by climate change when they exercise their powers. The insurance industry can also help by working with the Government to accurately identify the true economic impacts to change when it occurs.

As a key policy framework designed to mitigate the impact of climate change, IAG has for several years supported the introduction of an emissions trading scheme and a target to reduce Australia's greenhouse gas emissions in an economically efficient way. This support was articulated through initiatives such as the Australian Climate Group and the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change, and through submissions to Australian and international government reviews.

Engaging governments and participating in the global debate on a pollution reduction scheme continues to be an important aspect of the insurance industry’s efforts to mitigate climate change impacts.

Equally important to the insurance industry is engaging governments on related policy areas that are focused on encouraging community resilience including building standards, planning codes, government assistance in times of disaster and taxation reform.

Building standards

Research into the building damage caused by major natural disasters shows clearly that it is extremely important for the government to support community resilience by ensuring that new buildings in “at-risk” areas embody appropriate measures to withstand hazards such as cyclone, hailstorm, flood and fire.

Building code standards tend to focus principally on protecting life and safety. These are obviously vital priorities; however, it is also desirable to enhance building standards so that they cost-effectively protect the property itself, and its owner's financial interest, without sacrificing safety performance.

Such an approach, in improving the resilience of the built environment to severe weather and natural disasters, would also enhance the community's economic and social resilience to climate change.

It is worth noting that severe weather events can cause significant and costly physical damage to ancillary structures such as fences and sheds, because they are not currently covered by building standards or the building standards are poorly enforced. There is scope for further data analysis and research in this area in order to review the current situation. Working with the government to develop and share our knowledge of building vulnerability is imperative.

Furthermore, as some of the largest (direct and indirect) owners of real estate globally, insurers arguably have a role to play in driving the move to more greenhouse-friendly, energy-efficient buildings.Footnote 8

Planning codes

The government also plays an important role in risk-appropriate land-use planning and zoning, and insurers can work constructively with the government to ensure that planning properly recognises and manages risk.Footnote 9 Land that is, or becomes, at unacceptable risk from hazards such as bushfire, flood or coastal inundation should not be zoned for residential or commercial use. Without sound and consistent government controls, there is little to prevent ongoing building in locations of extreme vulnerability.

For those already located in areas extremely prone to bushfire, flooding or coastal inundation, relocation could be considered: however this option is problematic.

Planning regimes often involve more than one level of the government. In Australia, it is vital for Local and State Governments to be supported by a consistent Federal Government approach to these issues.

The insurance industry continues to participate in the public debate on how best to manage the risks associated with land use, for example through the Australian Parliament's Inquiry into Climate Change and Environmental Impacts on Coastal Communities.

Government assistance in times of disaster

When individuals elect not to insure their assets, they place a burden on the community because governments, in the absence of private insurance, are forced to take on the responsibility of “insurer of last resort”. There is an argument that individuals who cannot afford insurance should have access to government assistance when they are affected by a major insurable event; however, open-ended assistance is inequitable when provided to individuals who are able to insure responsibly but choose not to do so.

It can be argued that open-ended government assistance reduces the incentive for private insurance. Governments need to avoid interventions that promote dependence on government assistance and reduce incentives for self-reliance and personal responsibility. In so far as governments see a need to intervene to provide financial support to people who are not insured, then a counter-balancing policy-setting should be considered to ensure there remains continued incentive for prudent risk management. This could involve, for example, an income tax measure.

Taxation reform

The current regimes for the taxation of insurance in Australia fail to meet the generally accepted principles of simplicity, efficiency and equity. This contributes to under-insurance and non-insurance in Australia and, as a consequence, the need to call on the public purse in times of climate-related disasters.

A study by the Centre for International Economics (The General Insurance Sector: Big Benefits But Overburdened, 2005) found that taxes on general insurance in Australia are high by international standards and that “taxes on property insurance in most Australian states and territories are higher than in the majority of the comparator countries.”Footnote 10

A study by the Centre of Law and Economics, conducted for the Insurance Council of Australia, found that “State taxes (in Australia) have impacted the take-up of insurance and in doing so, caused deadweight losses to society.” The same report notes that these taxes on building and contents insurance in Australia can add between 18 per cent and 45 per cent to the cost of pre-tax premiums.Footnote 11

An Australian Treasury report (Architecture of Australia's Tax and Transfer System, August 2008)Footnote 12 found:

The narrow base of many transaction taxes and their interaction with other taxes can have an impact on resource allocation in the economy. For example, insurance products are subject to GST, insurance transaction taxes and, in some states, insurance companies can also be required to contribute directly to the funding of fire services. The interaction of these taxes increases the cost of premiums relative to other products, which may encourage people to take up less insurance than otherwise. An additional efficiency cost arises where a taxable product is used as a business input, since the tax can encourage businesses to use a less efficient mix of inputs. In addition, such input taxes cascade through the production chain to affect the market price of the final product, reducing international competitiveness.

The fire services levy is a poorly targeted mechanism for distributing the cost of fire services and not considered equitable. Indeed, data shows there is no correlation between the average levy collected and the incidence of fire call-outs. This reflects the fact that the levy is imposed on the total premium—which includes the full range of perils including storm and theft—and not just that proportion associated with fire.

Put at its simplest, the current fire services levy regime imposes tax on people who protect their property, businesses and personal possessions by insuring them. It is their taxes that pay for the fire fighting and protection services provided to the entire community. A fairer and more rational system would see all property owners pay for these services, spreading the burden equitably. A fire services funding system that encouraged full value insurance would result in economic and community benefits, especially as regards under-insurance.

In relation to stamp duty on insurance, we believe it is appropriate for the Federal and State Governments to examine a new set of undertakings beyond the current Intergovernmental Agreement to assist further reform of State taxation. A strong case can be made that reform of insurance taxes should have a high priority.

There is a clear social and economic case for eliminating, or at least reducing, insurance taxes and charges. Governments should recognise the essential benefits of insurance to the economy and community generally and implement a taxation system that does not penalise insurance relative to other more discretionary purchases.

Assisting communities to be more aware and resilient

Insurance is the ultimate community product, spreading risk to protect customers when risk becomes reality. When that does occur, insurers are central to the recovery effort. This means the industry has a unique opportunity to engage the community on climate change.

Education is an important first step in this process. No matter what action is taken at the global stage, communities need to come to grips with the potential ramifications of climate change. It is in the insurance industry's interest to educate the community on how to become more resilient to increasingly severe weather events, as well as how to reduce their impact on the environment. This includes conducting and sharing research that can feed directly into building and zoning codes, and providing tools for community action to lessen our collective carbon footprint.

Pleasingly, a number of initiatives are under way, which form part of a broader industry focus on building community resilience. For example, through the Insurance Council of Australia, insurers have developed an approach to increase resilience to severe weather, by risk management of the built environment, and encouraging policies and behaviours that underpin community resilience to extreme weather events. Insurers also invest in research and advocacy programmes designed to help communities withstand severe weather. For example, to test the resilience of roofing and housing materials to hail, IAG's direct insurance business has developed a hail gun that fires hailstones of varying size at roofing materials to simulate the impact of hail on roofs. The results of this research are made available to the public and to roofing product manufacturers. Similarly, seasonal advocacy campaigns provide valuable advice to communities on how to protect against bushfires in summer and storms in winter.

While education is important, the industry also needs to offer the community tools that they can use to reduce their impact on the environment. There are a number of ways insurers do this. For example, customers can access an insurer's online Greensafe Car and Greensafe Whitegoods energy-efficient profilers to help inform purchasing decisions based on environmental considerations.

Insurers can also encourage community action through financial incentives. For example, a large Australian insurer offers financial grants to grass roots community groups to help fund programmes that have a focus on environmental sustainability.

People in the community are most aware of the devastating impacts of extreme weather events immediately after they have been personally affected. This is also when customers are most aware of their insurers. When risk becomes reality, insurers need to make sure they are ready to deliver on the promise they made when they sold the policy. Managing claims after a natural disaster is important not only from a commercial and customer standpoint, but also in terms of maintaining the ‘right’ to lead the debate on climate change with customers and the community, as climate change is likely to increase weather-related risk in the future. It also allows insurers to work more effectively with customers on risk mitigation.

In response to the large claim volumes that follow extreme weather events, an Australian insurer has developed a mobile claims process through Mobile Emergency Rapid Response Vehicles, or MERRVs. These vehicles are satellite enabled, mobile claim centres, which allow customers to make claims on the spot, regardless of their location, and to get access to the advice and emergency help they need. This swift response helps the recovery process to start sooner, which in turn encourages community resilience.

Incentivising customers

Insurers can influence customer behaviour by giving them the tools they need to behave in a sustainable and environmentally-friendly way and also encouraging this behaviour through product and service offerings.Footnote 13 Product offerings that encourage and incentivise efficient energy consumption, and reward customers for being sustainable are simple and effective ways of making a difference.

For example, an Australian insurer offers Fuel Efficient Savings, which enable customers to save up to 10 per cent on their Comprehensive Car Insurance if they own a recognised fuel-efficient car. In New Zealand, personal and commercial insurance products are available which reward customers for being sustainable through energy efficiency, at home and on the road. NZI's Distinction and Echelon policies offer:

-

a 10 per cent discount for those who drive less than 5,000 kilometres a year—or 15 per cent if those customers also drive a hybrid or fuel-efficient vehicle;

-

contents cover that enables customers to replace whitegoods with energy-efficient equivalents; and

-

an additional A$20,000 on building claims to install sustainable features when rebuilding after a total loss.

One of the most difficult issues facing the Australian insurance industry is that of flood, which costs the community about A$300 million each year. There is no simple solution to insuring a natural peril that is already a significant threat in high-risk areas and may increase in frequency and/or severity as a consequence of climate change. This means that insurers, governments and the community will have to deal with flood events more often and more proactively.

In the past, insurance companies in Australia have not provided full flood cover, because of the difficulty in obtaining flood risk information and the problem with community rating a risk that is not entirely random.

In an attempt to address this problem, NRMA Insurance launched a flood insurance product in several Australian states, which automatically covers approximately 98 per cent of the community for flood, at minimal cost. The remaining 2 per cent of people live in high-risk areas and can choose to pay a premium that reflects how likely and how seriously they could be affected by flooding.

The general insurance industry has also worked hard to address the need for accurate flood mapping, which provides the necessary information to communities to manage the risk of flood and how it impacts the built environment. This is being achieved through the development and licensing of the National Flood Information Database by members of the Insurance Council of Australia in partnership with each of the Australian State Governments.

The National Flood Information Database is an address database, currently containing more than 11 million property addresses in Australia, overlayed with the known flood risk according to local government and government agency flood mapping.

This database can be used by insurers to help determine the flood risk to individual properties and by governments to examine property flooding risks and, if necessary, to implement flood mitigation programmes.

Currently, not every flood prone area in Australia is covered by the National Flood Information Database, as some local governments and agencies have yet to release flood mapping for their jurisdictions. However, it is frequently updated as flood mapping is released or existing flood mapping is improved by governments.

Leading by example and facilitating employee action

This paper has already outlined a number of ways in which the Australian insurance industry is taking a leading role in addressing the risks resulting from climate change. To have credibility with the key stakeholders in driving a multi-level approach to climate change, it is broadly acknowledged that the insurance industry must also lead by example.Footnote 14 This includes insurance companies managing their own environmental impact.

From our perspective, IAG has committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2012. We plan to achieve this target by implementing a range of measures, including:

-

the use of five star, green-rated buildings;

-

energy-efficient car fleets;

-

reducing fuel consumption;

-

minimising air travel;

-

monitoring office and print paper use; and

-

recycling waste.

Our progress in achieving these results is communicated to stakeholders on a regular basis. This is because we believe it is crucial not only to strive for carbon neutral targets, but to be transparent about how and whether they are being achieved.

Other practical action taken includes, for example, our support as a signatory to Climatewise, an initiative of The Prince of Wales's Corporate Leaders Group on Climate Change, which focuses on responding to the risks and opportunities posed by climate change. In addition, as a company with a very large investment portfolio of around $10 billion in funds under management, we align our investment philosophy with our broader sustainability framework. For some of our investments, this means targeting opportunities to support environmental, social and governance issues.

Climate change driven initiatives at a company level also require a commitment from employees if they are to be achieved successfully. It is, therefore, important for insurers to engage their people around their initiatives so they can make a contribution. Employees have already introduced some innovative approaches to carbon neutrality. For example, an Australian data centre has introduced a rainwater harvesting system to provide water needed to run the data centre's air conditioning systems, which are needed to keep information systems operational. It is estimated the system will save approximately 500,000 litres of water a year, displacing at least half of the data centre's main water requirements.

Conclusion

This paper outlines a practical and multi-level approach to addressing climate change, providing examples of initiatives currently being undertaken by the Australian insurance market. The approach and initiatives are aimed at harnessing the industry's unique understanding of risk as well as its relationships with key stakeholders, including governments, customers and the wider community.

The approach is also governed by the knowledge that insurance is the ultimate community product—it is all about managing and spreading risk around our society. If the industry is going to continue to play this important role, then it must be a sustainable business. This means tackling the challenges of climate change while balancing the needs of our shareholders, customers, people, communities and environment.

The approach and initiatives outlined in this paper do not provide all the answers to climate change risk, but contribute to the ongoing debate on this complex and critical issue in an attempt to facilitate some change. We must remain cognisant of the fact that our response to climate change in the years ahead will determine the shape of our industry for decades to come.

Notes

Refer, for example, to Mills (2009).

Herweijer et al. (2009, p. 371).

Hata (2009), Mills (2009, p. 330).

Mills (2009, p. 344).

References

Australian Treasury (2008) Architecture of Australia's tax and transfer system (August), Commonwealth of Australia, p. 293.

Bureau of Transport Economics (2001) Economic Costs of Natural Disasters in Australia (January), p. 13.

Centre for International Economics (2005) The General Insurance Sector: Big Benefits but Overburdened (August), p. 24.

Tooth, R. and Barker, G. Centre of Law and Economics (2007) The Non-Insured: Who, Why and Trends (May), Insurance Council of Australia, p. 37.

Faust, E., Herweijer, C. and Knap, A.H. (2009) Physical Effects of Climate Change from an Insurance Perspective, The Geneva Reports: The insurance industry and climate change—contribution to the global debate No 2 (July), p. 30.

Hansen, K.D. (2009) The Landscape of Climate Cooperation between Governments and the Insurance Industry, The Geneva Reports no2: The insurance industry and climate change—Contribution to the global debate (July), pp. 73–81.

Hata, H. (2009) Leadership by Insurance: How the Insurance Industry can Establish Best Practices in Its Business Models Related to Climate Change, The Geneva Reports no2: The insurance industry and climate change—contribution to the global debate (July), pp. 97–104.

Herweijer, C., Ranger, N. and Ward, R.E.T. (2009) ‘Adaptation to climate change: Threats and opportunities for the insurance industry’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 34 (3): 360–380.

Mills, E. (2009) ‘A global review of insurance industry responses to climate change’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 34 (3): 323–359.

Munich Re Insurance Information Institute (2009) 2008 Natural Catastrophe Review (January), pp. 31 and 37.

Wallin, U. and Bosse, C. (2009) Insurance and Climate Change: From Reaction to Pro-Action, The Geneva Reports no2: The insurance industry and climate change—Contribution to the global debate (July), p. 69.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilkins, M. The Need for a Multi-Level Approach to Climate Change—An Australian Insurance Perspective. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 35, 336–348 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2010.8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2010.8