Abstract

Australia has a universal, compulsory, public health insurance scheme that includes insurance rebates for private fee-for-service medical practitioner services. Recent sweeping changes to the rebates for general practitioner (GP) services provide an opportunity to observe the effects of widespread insurance changes on the behaviour of GPs and aggregate outcomes such as quantities, prices and co-payments. In this paper, we study the effect of two important changes to subsidies for GP services, the first of which increased the rebates payable for services provided to specific patient groups, and the second of which increased rebates payable for all patients. Using economic theory, predictions of the effect of the rebate increase on quantities, prices and co-payments are produced that depend on the structure of the market. Using time-series data, we then present short-run empirical evidence that suggests that the supply curve for GP services is backward-bending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Australia has a national health insurance system (Medicare) that provides insurance rebates for medical services provided out of hospital by private medical practitioners with “approved provider” status.Footnote 1 The medical services covered by this system are listed in the Medicare Benefits Schedule.Footnote 2 The Schedule also specifies a fee—the Schedule Fee—which forms the basis of the calculation of the rebate provided for each service. Until January 2005, this rebate was set at 85 per cent of the Schedule Fee for out-of-hospital services (subject to safety net provisions that cap the cumulative annual difference between the Schedule Fee and the rebate).

Under this insurance scheme, medical practitioners are not required to adhere to the Schedule Fee for that item but are free to set the price per service on whatever basis they choose. Consumers pay the difference between the rebate and the price actually charged for each service. The rebate then takes the form of a fixed per unit subsidy (as opposed to an ad valorem subsidy) with the consumer's payment being a rear-end deductible (the value of which depends upon the price of the service). Effectively, the rebate sets a floor price for medical services—a price below which the fee charged for an item of service cannot fall.Footnote 3 Depending upon, among other things, the degree of competition in the relevant market area, medical practitioners may accept the floor price in full payment for the service resulting in no payment being made by the consumer for that item of service. As expected, evidence suggests that practitioners working in areas of lower doctor supply (generally, in Australia, non-urban, rural and remote areas) have greater market power and on average charge fees that exceed the floor price by a greater margin than their counterparts working in urban and metropolitan areas.Footnote 4

Practitioners who choose to accept the rebate as full payment for an item of service are permitted to bill the government insurer directly, and the consumer co-payment is zero. Under these circumstances, practitioners can accumulate claims and submit them “in bulk” to the insurer, leading to the description of this pricing behaviour as “bulk-billing”. If not bulk-billing, practitioners bill the patient for the service with the patient claiming and receiving the rebate from the insurer.

In the mid-1990s, following a period of sustained increases in the per capita number of general practitioners (GPs), in the per capita consumption of general practitioner (GP) services and in the proportion of services bulk-billed, the Commonwealth government implemented various measures aimed at reducing the supply, or the rate of growth in supply, of GP medical services. These measures included tightening the criteria for “approved provider” status under the national health insurance scheme and restricting the immigration of doctors. In the ensuing years, these supply-reducing measures were associated with a reversal in the previous trends, leading government to reconsider policies towards GPs. For example, in 2002 a “Fairer Medicare” package was proposed only to be replaced prior to implementation by a “Medicare Plus” proposal following a variety of criticisms of the original package of measures.Footnote 5

The present paper is concerned with analysing the effects of two policy initiatives introduced in the mid-2000s on the prices and quantities of GP services. One of these, a component of the Medicare Plus package introduced with effect from 12 January 2004, provided a bulk-billing bonus of $5 per service for each bulk-billed GP service provided to individuals aged 16 years or less and to people with Health Care Cards.Footnote 6 The other more extensive initiative, which came into effect on 1 January 2005, increased the Medicare rebate for all GP services from 85 per cent to 100 per cent of the Schedule Fee.

Economic theory suggests that the effects of these changes in insurance arrangements on GP markets will depend upon the degree of competition in the market, the characteristics of the equilibrium in these markets prior to, and subsequent to, the changes, and the elasticities of supply and demand. This theory is reviewed in the following section of the paper where it is shown that the direction of the effects on prices and quantities is expected to be the same regardless of the degree of competition (although the magnitudes of the changes may differ). However, regardless of the market structure, the design of the insurance scheme suggests that the pre- and post-change characteristics of the equilibrium in the market can be expected to be of considerable importance. This theoretical section also alludes to the possibility of a backward-bending supply curve of labour for GPs as this can also have implications for the effects of the policy changes. Then follows a discussion of our empirical analysis that estimates the effects of the policy initiatives using time-series analysis of national data that embrace the introduction of the changes. The data, method and results are presented in this section, while the closing section summarises our conclusions.

Theory

The Medicare rebate is a fixed subsidy per item of service. Both policy changes that are the subject of interest in this paper have the effect of increasing this subsidy, the first for a subset of consumers of GP services (those aged 16 years or less and Health Care Card holders) and the second for all consumers of GP services. The theoretical analysis that follows is, in general, the same for the two policy changes. However, the empirical effects of the second policy can be expected to be much more pronounced because of its ubiquitous impact on consumers of medical services. Therefore, in this section, we provide a theoretical treatment only of the more extensive policy initiative, on the understanding that the same analysis applies to the more restricted policy change.

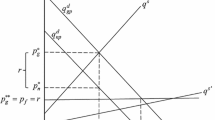

Let s denote the Medicare subsidy per unit of medical services and Δs the increase in this subsidy because of the increase in the rebate from 85 per cent to 100 per cent of the Schedule Fee. The effect of this increase in the subsidy on the prices of medical services will depend upon the characteristics of the equilibrium and the degree of competition in the market. Furthermore, the incidence of the subsidy will depend on the elasticities of demand and supply. The analysis that follows considers first the case of competitive markets. The equilibrium will exhibit one of the following three characteristics: (a) the floor price for medical services set by the Medicare rebate/subsidy is binding both before and after the increase in subsidy; (b) the floor price is not binding before the increase in subsidy but becomes binding after the increase in subsidy; or (c) the floor price is not binding either before or after the increase in subsidy. Following this discussion, the analysis is repeated under conditions of monopoly.

Competitive markets

The three panels in Figure 1 illustrate the three possible equilibria that can characterise the market for medical services. In Figure 1a, D(p g ) is the market demand curve for medical services as a function of the gross price p g and analogously for D(p n ), where p n is the net price (gross price minus subsidy).Footnote 7 The floor price p f , which is equal to the original per unit subsidy s, is binding (i.e. it lies above what the equilibrium gross price would be in the absence of the subsidy). The quantity demand is D 1 while the quantity supplied is S 1, giving rise to excess supply at the floor price. The market price of medical services is then equal to the Medicare subsidy and the net price (consumers’ out-of-pocket expense) is zero. In Australia, this equilibrium is characterised as “bulk-billing” as GPs will bill the national health insurance scheme “in bulk” for all services rendered and will accept the per unit subsidy as full payment for the service.

Three equilibrium outcomes under competition: (a) zero co-payment before, and following, an increase in the subsidy; (b) positive co-payment before an increase in the subsidy, but zero co-payment after the increase in the subsidy; and (c) positive co-payment before and after an increase in the subsidy.

Now let the subsidy increase by Δs. This increases the floor price to p′ f =p f +Δs and also shifts the demand curve to D′(p g ), where the vertical displacement of the demand curve is also Δs. The effect of this is to leave the quantity demanded of medical services unchanged, reflecting the fact that the net price of medical services remains unchanged at zero after the increase in subsidy. The desired quantity supplied of medical services, however, increases to S 2 resulting in an increase in excess supply of medical services in this market.

All medical services will continue to be bulk-billed and the subsidy will make no difference to the net price to consumers, which remains at zero. This result holds regardless of the own-price elasticity of supply. Even if this elasticity is zero, excess demand remains at the same level as in the initial equilibrium, and bulk-billing of all services will continue.Footnote 8 In this case, the increase in subsidy leads to an increase in market price that is equal to the subsidy—GPs capture all of the increase in subsidy—and the quantity of medical services traded remains unchanged.

Figure 1b depicts the situation where the floor price for medical services is not binding in the initial equilibrium but becomes so after the increase in subsidy. The initial demand and supply curves D(p g ) and S(p g ) give rise to the initial equilibrium price and quantity (p e , q e ), where the equilibrium price is above the floor price p f . This equilibrium is not characterised by bulk-billing and the net price p n is greater than zero. When the subsidy is increased by Δs, there is excess supply at the new floor price p′ f so the new market equilibrium is characterised by bulk-billing. In this case, the increase in the subsidy leads to an increase in the market price, a reduction in the net price to zero and an increase in bulk-billing. However, the increase in market price is less than the increase in subsidy—GPs capture only a part of the increase in subsidy with the remainder being captured by consumers as reflected in the fall of the net price to zero. The quantity of medical services traded increases from q e to D 2.

The third case is shown in Figure 1c. In the initial equilibrium, the market price p e exceeds the floor price p f and the net price is positive at p n . The equilibrium quantity traded is q e . The increase in subsidy Δs causes the market price to rise to p′ e . Unless supply is perfectly price inelastic, this increase in market price will be less than the increase in subsidy (i.e. p′ e −p e <Δs) and consumers will reap some of the benefit of the increase in subsidy through a fall in the net price from p n to p′ n . If supply is perfectly price inelastic, the increase in market price will equal the increase in subsidy and the net price will remain unchanged, that is, GPs will capture the full value of the subsidy.Footnote 9

Monopoly markets

The analysis of these three scenarios under conditions of monopoly is illustrated in the three panels in Figure 2. In Figure 2a, the gross price demand curves D(p g ) and D′(p g ) are truncated at quantity demanded D 1, where the net price is zero. Unless paying consumers to consume services is an option, the quantity demanded cannot exceed D 1 (i.e. negative net prices are inadmissible). Given this constraint and the marginal cost curve MC, the profit-maximising quantity of services is D 1, with all services being bulk-billed at the floor price p f = s or the Medicare rebate. The increase in subsidy Δs causes a vertical displacement of the demand and marginal revenue curves by the same amount and, as is evident in Figure 2a, bulk-billing of all services continues with the GPs capturing all of the increase in the subsidy. The quantity of services provided remains unchanged.

Three equilibrium outcomes under monopoly power: (a) zero co-payment before, and following, an increase in the subsidy; (b) positive co-payment before an increase in the subsidy, but zero co-payment after the increase in the subsidy; and (c) positive co-payment before and after an increase in the subsidy.

Figure 2b shows the case where the initial equilibrium is not characterised by bulk-billing but the monopolist moves to bulk-billing following the increase in subsidy. The equilibrium price p e increases following the increase in subsidy, with the new profit-maximising price being p′ f (the new floor price). The net price p n falls to zero, characterising the bulk-billing outcome, and the quantity traded increases from q e to D 1.

The third case—no bulk-billing before or after the increase in subsidy—is shown in Figure 2c. The market price rises from p e to p′ e but this price increase is less than the increase in subsidy. This is because the profit-maximising quantity for the monopolist has increased from q e to q′ e and to sell that additional output the market price cannot be increased by the full increase in the subsidy. This results in a fall in the net price p n to p′ n .

The effects of the increase in subsidy under competitive and monopoly conditions are summarised in Table 1. The expected directions of effect on price (gross and net), quantity of services and quantity of bulk-billed services are the same under both sets of market conditions and vary according to whether the pre- and post-change equilibria in the market are characterised by bulk-billing. The overall impact of the subsidy will depend upon the extent to which these equilibria prevail in the various sub-markets for GP services.

Note that the foregoing analyses for monopoly markets are applicable not only to the case of pure monopoly, but of other market structures (e.g. monopolistic competition) in which producers have market power and hence face downwards-sloping demand curves.

In concluding this theoretical discussion, an implicit assumption about the net price demand curves in both the competitive and monopoly models warrants mention. Specifically, the analyses have assumed that the net price demand curve has a single-valued correspondence with quantity at a zero price. This assumption underlies the conclusion that an increase in the subsidy will have no impact on quantity traded in markets characterised by pre- and post-change bulk-billing, as summarised in the equilibrium (a) scenario Table 1. It is possible that the demand curve may exhibit a multivalued correspondence with quantity at a zero net price, implying an infinite price-elasticity of demand at that price. Under these circumstances, an increase in the subsidy may lead to an increase in quantity traded, as it does in the equilibrium (b) and (c) scenarios in Table 1.Footnote 10 This may not be a likely outcome when it is recalled that the zero net price is the out-of-pocket price at the point of service and does not include waiting time and transactions costs—consumers still confront other costs associated with GP attendances in addition to the out-of-pocket price at the point of service. Importantly though, even if a multivalued correspondence at a zero net price exists, it gives rise to a positive change in quantity traded under the equilibrium (a) scenario, that is, a change in the same direction as under the equilibrium (b) and (c) scenarios. A negative change in the quantity traded following an increase in subsidy could not therefore be attributed to this multivalued correspondence.

Empirical analysis

In this section, we present some econometric evidence on the impact of recent changes to the subsidy arrangements for GP services.

Data and methods

In the analyses presented in this section we employ quarterly data on the quantities, prices, expenditures, subsidies and bulk-billing rates for all GP services (“GP/Vocationally Registered GP (VRGP) attendances”) provided under the Medicare scheme during the period 1991(1)–2005(2).Footnote 11 Unfortunately, the data for subsequent quarters is (with the exception of quantity data) no longer publicly available. Importantly, though, the available data does allow a very useful distinction to be invoked between those services that are patient-billed (p g >s → p n >0) and those that are bulk-billed (p g =s → p n =0). This distinction is useful, because it enables one to distinguish movements in the gross price from those markets in which p g >p f . This could be an important consideration because, as was shown in the preceding section, the increased subsidy serves to increase p g in bulk-billing markets, even when p n remains zero. Thus, the more interesting question concerns the effects of the subsidy change when one excludes bulk-billed services from the analysis. Due to the unavailability of data, our analysis is thus limited to the period 1991(1)–2005(2), but the available data enables us to produce more extensive analyses than are possible with the very limited data that is now publicly accessible.

Although Medicare data is available for the period 1984(3)–2005(2), the service data that is appropriate for the question this paper seeks to address pertains to the period 1989(4)–2005(2), only. Prior to the regression analysis, based on a preliminary inspection of the time-series data, we decided however to set the start of the sample period to 1991(1). This decision was motivated by the somewhat erratic time series in the first few years following the introduction of vocational registration (VR) in 1989(4).Footnote 12 At the conclusion of our regression analysis we did, however, reset the sample period to include the five omitted observations, to see if our results were sensitive to this decision. We found that, while the fit of the regressions generally worsened as a consequence, our results were otherwise unaffected.

To analyse the impact of recent changes to the Medicare arrangements, and based on our preliminary inspections of the data, we specified a number of single-equation, first-order auto-regressive (AR(1)) time-series regressions, incorporating an intercept (Constant), trend (t), three seasonal dummy variables (DVJUNE, DVSEP, DVDEC) and two policy dummy variables: DVBBI and DVΔs. DVBBI represents the first policy shock of interest (the bulk-billing bonus): it involved the provision of incentives for GPs to bulk-bill specific groups of consumers, namely children under 16 years and Health Care Card holders. DVΔs represents the increased subsidy for GP services that took effect on 1 January 2005. (The latter variable was the focus of the preceding sections of the paper.) We also created year dummies for the t−1 years in the sample and, although we experimented by adding these to our preliminary model, found that they did not improve the fit.

We chose to specify each dependent variable, other than the bulk-billing rate, in natural logarithms. This decision also was based on our initial inspection of the data. The specification of the dependent variables in natural logarithms has an added interpretive convenience: the resulting time trend and dummy variable parameter estimates are estimates of the instantaneous quarterly growth/decay rate of the dependent variable.

Results

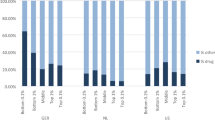

Bulk-billing rates and quantities of GP services

The results in Table 2 indicate that both the bulk-billing incentives that were introduced in 2004 (DVBBI) and the subsidy increase in January 2005 (DVΔs) increased the proportion of GP services that were bulk-billed. The increases were approximately 2.2 and 1.7 percentage points, respectively.Footnote 13 Interestingly, these increases in bulk-billing rates were not reflected by statistically significant increases in the quantities of GP services that were bulk-billed. The statistically insignificant coefficients on DVBBI and DVΔs (regressed on log quantities of GP services bulk-billed) are shown in Table 3.

Further insight on the effects of the two policies of interest can be gleaned by examining their impacts on the quantities of all GP services provided. The regression results on the total quantity of GP services (i.e. patient- plus bulk-billed services) are reported in Table 4. Note that the coefficient on DVBBI is numerically and statistically insignificant, suggesting that the targeted 2004 bulk-billing initiative had no discernible effect on quantities. The coefficient on DVΔs, on the other hand, suggests that the 2005 subsidy increase had a negative effect on total quantities. The estimated effect is a reduction of 7 per cent in total quantities and this result is statistically significant at the 5 per cent level.

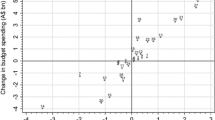

Taken together, the results in Table 2 suggest that the proportion of services bulk-billed increased by around 4 percentage points while the results in Table 4 suggest that the increase in the subsidy in January 2005 reduced the overall quantity of services by 7 per cent. In terms of the conventional comparative statics results obtained using supply and demand curves earlier in this paper, this latter result is unexpected—with a positive price elasticity of supply, some expansion in service volumes was predicted, and even with a zero price elasticity of supply, no change in service volumes would be expected.

One theoretical explanation for the reduction in total quantity of services is that the GP labour supply curve is backward-bending.Footnote 14 Another is that, in the face of increasing demand, the non-price determinants of demand such as waiting times increased, offsetting the effect of the increase in the subsidy on supply and causing the full price of medical services to increase and the total quantity of services to fall. We believe that a backward-bending GP labour supply curve is a plausible explanation of this result for two reasons. First, GPs in Australia are predominantly privately employed independent professionals with a considerable degree of choice regarding the number of hours that they work. Second, in comparison with average weekly earnings, GPs would earn considerably higher incomes than this average if they worked the same number of hours. The income effect of a higher wage rate for GPs, which would tend to reduce their number of hours worked (assuming leisure is a normal good), is therefore more likely to dominate the substitution effect that would tend to increase their number of hours worked.

A further piece of evidence on the quantity effects of the policies is presented in Table 5, which reports time-series regression results on the (log) quantities of patient-billed GP services only. The negative coefficient on DVBBI is statistically insignificant, but note the negative and statistically significant sign on DVΔs. The latter suggests a 12 per cent decline in the quantity of patient-billed GP services provided under the Medicare scheme. In theory, there are at least two possible effects on quantities that the coefficient on this exogenous shock dummy might capture. For convenience, coin these two effects a “zero-sum-quantity” effect (ZSQ) and a “non-zero-sum-quantity” effect (NZSQ). A ZSQ effect arises when GPs decide to bulk-bill services that would previously have attracted a co-payment due to the exogenous shock. In other words, the ZSQ effect measures the extent to which patient-billed services “become” bulk-billed services. An NZSQ effect arises when GPs reduce or increase the quantity of services per se as a result of the shock. The latter involves a real net change in the number of services provided, rather than simply a reduction of the gross prices of some previously patient-billed services to p g =s. Recall that Table 4 suggests the total quantity of services declined by approximately 7 per cent. Thus, it would appear that approximately 5 per cent of services that were previously patient-billed were bulk-billed following the subsidy increase of January 2005. This inference accords with the result in Table 2 showing a 4 percentage point increase in the proportion of services that were bulk-billed being attributable to this policy.

In summary, these results suggest that the bulk-billing incentives introduced in 2004 and the increase in the subsidy of 1 January 2005 both increased the proportion of GP services that were bulk-billed. Interestingly, the 2005 subsidy increase was associated with a reduction in overall service volumes, while the targeted bulk-billing incentive of 2004 had apparently no impact on such volumes.

Prices

In this section, we examine the effects of the two policy shocks discussed so far on the mean gross price (p̄ g ) and mean net price (p̄ n ) of GP services. With the data available to us it was possible to compute (i) p̄ g and p̄ n defined over all (i.e. patient- plus bulk-billed) GP services and (ii) p̄ n defined over patient-billed GP services, only. It was not possible to compute p̄ g defined over patient-billed GP services, only.Footnote 15

Gross prices

Consider first the impact of the policies on the mean gross price of all GP services (p̄ g ). Table 6 presents the regression results, conditioning ln(p̄ g ) of all GP services, by quarter, on the independent variables that were employed in the regressions reported above. Once again directing attention to the two policy variables of interest, note that the bulk-billing incentives had no measurable effect on the gross prices of GP services. By contrast, note the positive and statistically significant effect of the variable DVΔs (the across-the-board increase in subsidy). The coefficient (0.11) suggests that this increase in the subsidy for GP services has given rise to an 11 per cent increase in the mean gross price of GP services. This result accords with our expectations, as outlined in the theoretical introduction to this paper.

Net prices

Consider now the effect of Δs on the mean net prices paid by consumers, p̄ n . Table 7 presents the results of regressing ln(p̄ n ) on the trend, seasonal and policy variables employed above. The policy variables DVBBI and DVΔs are, once again, of primary interest. First, note that the signs on both variables are positive and the coefficient on DVBBI is also statistically significant. The coefficient on DVBBI suggests that the bulk-billing incentive was associated with a 7 per cent increase in the out-of-pocket price charged to patients whose GP services were not bulk-billed. This net price increase is presumably confined to the sub-population that does not qualify for the bulk-billing bonus as a result of the 2004 bulk-billing incentives since, by definition, the bonus only applies when the zero net price is charged.Footnote 16 As with the reduction in overall service volumes noted above, this increase in net price does not accord with the predictions of conventional supply and demand analysis (see Table 1) but is consistent with the existence of a backward-bending supply curve of GP labour. It is also consistent with increases in non-price determinants of demand such as waiting times and transactions costs consequent to the increase in demand induced by the increase in subsidy, as mentioned previously.

Relationship between gross prices and net prices

As indicated by the theoretical analysis, it is possible that the effect of Δs could be gross-price-inflationary and simultaneously net-price-neutral or decreasing. For example, consider a market such as that depicted in Figures 1a and 2a, in which the bulk-billing outcome obtains both before and after Δs (see also row (a) in Table 1). In this instance, the increase in the subsidy from 85 per cent to 100 per cent of the Schedule Fee can be expected to increase p g by 17.6 per cent (i.e. p′ f /p f =1/0.85=1.176) even though Δp n =0=p n . In contrast, in markets characterised by no bulk-billing pre- or post-policy change (Figures 1c and 2c, and row (c) in Table 1), the increase in p g and reduction in p n depend upon the price-elasticities of supply and demand. Given the preponderance of bulk-billing in GP markets in Australia, it is to be expected that a substantial component of the increase in the subsidy in 2005 would be reflected in an increase in p g for all services. The estimated increase in p g attributable to Δs of 11 per cent accords with this expectation.

It is perhaps ironic that the largest proportional gross price increases occur in bulk-billing markets where net price remains unchanged, that is, Δp n =0=p n . Consider those markets in which p n >0 prior to Δs. Assuming a positive price-elasticity of supply (under competition) or a positively sloped marginal cost curve (under monopoly), the introduction of the policy change that gives rise to Δs is expected to reduce the net price either to zero (see Figures 1b and 2b) or some value greater than zero (Figures 1c and 2c). Therefore, since the gross price is not increased by the full value of the subsidy (Δp g <Δs), the proportional change in the gross price will be less than that in the bulk-billing scenario (Figures 1a and 2a).Footnote 17 Consider a simple illustrative example, in which the set of prices and subsidies prior to Δs is p̄ g =$100; p f =s=$85; and p n =p g −p f =p g −s=$15. Now, suppose the subsidy increases to $30 (Δs=$15=Δp f ). Suppose also that the GP captures most of this increase, say $14, implying that the reduction in net price is $1. In this instance, the gross-price-inflation in percentage terms is [(p′ g /p g )−1] × 100=14 per cent. Even if the price-elasticity of supply is zero (or the marginal cost curve is vertical), allowing the GP to capture fully the increase in subsidy, the percentage increase in gross price in this example is 15 per cent, less than the 17.6 per cent characterising the bulk-billing outcomes.

By similar logic, and since the bulk-billing rate is known, it is possible to provide an approximate answer to the question of how much, on average, gross prices increased in patient-billed markets as a result of Δs. This answer involves the implicit and weak assumption that net prices at least did not rise in those markets where p n >0. (This assumption is, in fact, borne out by the empirical results presented earlier that suggested a fall in net prices.) Our results shown in Table 6 suggest that Δp̄ g /p̄ g across all (i.e. patient-billed and bulk-billed) GP services was approximately 11.0 per cent (the 95 per cent confidence interval was approximately 10–12 per cent). We know that 71 per cent of GP services were bulk-billed in the period of interest, and that Δp̄ g /p̄ g for such services is approximately 17.6 per cent. If market prices in the patient-billing sector of the market were entirely unaffected by Δs (i.e. there were no competitive effects in the patient-billing market), the expected change in gross prices would be 0.71 × 17.6=12.5 per cent. Note that this estimate lies above our point estimate but falls at the upper end of our confidence interval, above. To derive a point estimate of 11 per cent, this means that gross prices in patient-billed markets must have increased by less than 11 per cent. It is simple to compute the magnitude of this increase for patient-billed services that would generate the overall mean percentage increase in gross price of 11 per cent. It involves solving for x in the following expression for the weighted mean percentage increase in gross price:

This gives x=−5.16 per cent, that is, a fall of the mean gross price for patient-billed services of around 5 per cent is consistent with our estimate of an 11.0 per cent increase in the market gross price across all services. This deduced result implies that net prices for patient-billed services also fell and is consistent with the negative, albeit statistically insignificant, result on the reported coefficient for DVΔs in Table 7.

Conclusions

In the mid-2000s, Australia introduced two important policy changes that increased the insurance rebates in markets for GP services—a bulk-billing bonus that increased the rebate for MBS services provided to a defined subset of the population, and an across-the-board increase in this rebate. This paper has provided a theoretical analysis of the general effect of these subsidy changes on prices and quantities of GP services under conditions of both competition and monopoly. This analysis demonstrated that, regardless of which of these two market structures prevail, in markets characterised by bulk-billing before the increase in subsidy, bulk-billing will continue after the increase in subsidy and GPs will capture all of the increase in subsidy as an increase in market (gross) price. In markets not characterised by bulk-billing before the increase in subsidy, net (out-of-pocket) prices will fall, perhaps even to zero, unless the price-elasticity of supply is zero (under competition) or the marginal cost curve is vertical (under monopoly). An increase in the quantity of GP services provided can be expected to occur only in those markets not characterised by bulk-billing before the increase in subsidy. As bulk-billed services account for around 70 per cent of all GP services in Australia, the effects of the subsidy in these markets can be expected to dominate overall market outcomes.

Empirical analysis of time trends in prices and quantities of GP services has borne out most of the predicted effects from the theoretical analysis. The first policy change, which targeted a particular sub-set of the population, appears to have had no measurable effect on mean gross prices for all services and only a small but statistically significant effect on net prices for patient-billed services. The second policy change, an across-the-board increase in subsidy of approximately 17.6 per cent affecting all GP services led to an estimated 11 per cent increase in gross prices of all services. This 11 per cent increase comprises a 17.6 per cent increase in the gross price of bulk-billed services and a 5 per cent decrease in the gross price of patient-billed services. The policies appear to have reduced the quantities of services provided by GPs slightly, while increasing the proportion of services bulk-billed.

The reduction in the quantity of services following the increase in the subsidy (the second policy change) is unexpected but suggests an interesting possibility—that the supply curve of GP labour is backward-bending. This possibility is also suggested by the estimated effect of the bulk-billing incentive (the first policy change) on net price—a 7 per cent increase rather than the expected result of a zero or negative change. These two unexpected results are also consistent with an alternative hypothesis that, in response to these policy changes, some non-price determinants of demand (e.g. waiting times) have changed so as to offset the net-price-reducing effects of the policy change. We conclude, however, that the backward-bending supply curve explanation is more plausible because of the relatively high incomes of GPs and the flexibility they have as independent professionals to vary their hours of work.

Notes

1 Rebates are also paid for some in-hospital medical services but these are not the subject of the present paper.

5 The “Fairer Medicare” package was critically analysed in several papers by Savage and others (see Savage, 2003; Savage and Jones, 2004; Jones et al., 2004).

6 The Health Care Card entitles holders to higher subsidies for pharmaceuticals listed on the pharmaceutical benefits schedule and a limited number of additional concessions on health and other services (depending upon the local and state jurisdictions; see Australian Government, 2012). All dollar amounts reported in this paper are denominated in Australian dollars.

7 While this analysis concentrates on money prices as a determinant of demand, non-price determinants of demand such as waiting times and transactions costs may also be important determinants of demand.

8 It is possible that some GPs will have a backward bending supply curve of labour over this range of prices. If such GPs have a sufficiently large share of the market, this supply response could cause the market supply curve to be downward sloping over this range of prices. It is, however, likely that even if this was the case, the relative slopes of the demand and supply curves would result in a stable equilibrium. Otherwise, any disturbance to the initial equilibrium would cause an upward price spiral, a situation that is not observed in reality.

9 If the supply curve is backward-bending, then both gross price and net price may increase, that is, GPs may capture more than the full value of the subsidy. The quantity of services traded would also be lower than in the initial equilibrium.

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for drawing this point to our attention.

These services, in turn, are part of the set “unreferred attendances”. In addition to “GP/VRGP attendances”, this latter category contains (recently added) “nurse practitioner” and “enhanced primary care” Medicare Items, and unreferred consultations with specialist medical practitioners. Fortunately, for the purposes of this analysis, (i) unreferred attendances by non-GPs are separable (and labelled “other” unreferred attendances); and (ii) the subsidy changes in which we are interested were inapplicable to unreferred attendances by specialists.

The VR scheme was introduced in December 1989. This scheme provided a greater subsidy per service to Fellows of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). To be eligible for Fellowship, MBBS degree holders were required to pass further RACGP tests. Moreover, to maintain Fellowship status, GPs were required to undertake sufficient continuing medical education activities, as defined by the RACGP and measured via a points system.

The bulk-billing rate in the December quarter 1993, just prior to the introduction of the bulk-billing initiative in January 2004, was 75.8 per cent.

Using GP survey data, a study by Access Economics Pty Ltd (2002) found evidence of a backward-bending supply curve for GPs, as did a more recent study by McRae (2009) using administrative data. However, both studies generally found that the backward-bend occurred at prices/quantities considerably above the mean values in their samples.

The complication pertains to the fact that, although patient contributions for patient-billed services were available, along with the numbers of patient-billed services, the Medicare subsidies paid were aggregated across patient-billed and bulk-billed services. Although assumption-based approximations were considered (e.g. an approximation based on the assumption that the GP case mix, as represented by Medicare Items, was identical across bulk-billing and patient-billing practitioners), the veracity of such approximations would be questionable.

We also regressed the log expenditures (Medicare subsidies plus patient contributions) on GP services under Medicare on the same independent variables. The results of this regression were consistent with the results reported above on prices, quantities and bulk-billing: neither of the policy variables had a statistically significant effect on expenditures.

Implicitly, we assume no collusive oligopoly or cartel behaviour that could increase both gross price and net price.

References

Access Economics Pty Ltd (2002) An Analysis of the Widening Gap between Community Need and the Availability of GP Services, Report for the Australian Medical Association, Canberra.

Australian Government (2012) ‘Centrelink’, from http://www.centrelink.gov.au/internet/internet.nsf/payments/conc_cards_hcc.htm#what, accessed 6 January 2012.

Butler, J.R.G. (1994) ‘Cuts in subsidies and supply restrictions under Medicare: A positive political economy analysis’, in M.R. Johnson, P. Kriesler and A.D. Owen (eds.) Issues in Australian Economics, Sydney: Allen and Unwin, pp. 109–124.

Connelly, L.B. and Doessel, D.P. (2002) Medicare and General Practice: An Economic Analysis, Australian Studies in Health Services Research (Monograph Series) No. 91, School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Department of Health and Ageing (2012) ‘Medicare benefits schedule’, from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/mbsonline/publishing.nsf/Content/Medicare-Benefits-Schedule-MBS-1, accessed 6 January 2012.

Jones, G., Savage, E. and Hall, J. (2004) ‘Pricing of general practice in Australia: Some recent proposals to reform Medicare’, Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 9 (Supplement 2): 63–68.

McRae, I. (2009) Supply and Demand for GP Services in Australia, Australian Centre for Economic Research on Health, Research Report No. 6, July 2009.

Savage, E. (2003) ‘Equity, payment incentives and cost control in Medicare: An assessment of the government's proposals’, Health Sociology Review 12 (1): 5–16.

Savage, E. and Jones, G. (2004) ‘An analysis of the general practice access scheme on GP incomes, bulk-billing and consumer co-payments’, Australian Economic Review 37 (1): 31–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Connelly, L., Butler, J. Insurance Rebates, Incentives and Primary Care in Australia. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 37, 745–762 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.40

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.40