Abstract

The study investigates the most relevant factors affecting business students’ choice of a career in the insurance industry. Recent industry surveys indicate that students find the insurance profession uninteresting and so are reluctant to pursue a career within it. However, many of the survey respondents showed an interest in the profession. We tested three hypotheses to determine whether student choices are affected by environmental, opportunity and awareness factors. The study applied structural equation modelling and regression analysis to the data and finds that nationality, together with other environmental factors, significantly affects their choice of the insurance profession. In addition, we found that students are unaware of the underlying philosophy of insurance businesses, their products and their vital role in the economic and social system. The lack of adequate research, education providers, and the shortage of study materials and inadequate marketing strategies are among the key causes of students’ reluctance to engage with the insurance profession. This study may assist insurers, educators and professional bodies to develop their strategy directed towards attracting talents to the insurance industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skills and talent are vital to all businesses irrespective of their size, type or the market economic conditions.Footnote 1 The disparity between the supply and demand of talent (the “talent gap”) may have a detrimental impact on business. Recent observations show that the number of business and management students preparing insurance degrees has declined worldwide, as noted in many developed and developing countries where insurance companies are struggling to find skilled talents. At the 2007 Xchanging conference in London, Richard Ward, then Lloyd’s CEO, cautioned with alarming information that the £100 billion U.K. insurance industry, regarded as the second largest national export, with a 330,000 workforce playing diverse roles plus a further million people in related fields, is in imminent danger due to the shortage of highly skilled talents. He commented, “Yet nearly 90 percent of graduates do not consider a role in insurance and 75 percent of recruiters in the industry struggle to attract quality talents”.Footnote 2 The shortage of talent in insurance is also acknowledged in a U.K. parliamentary study that emphasised “promoting the insurance industry as an attractive career choice and improving the image of the industry within schools and universities”.Footnote 3

In 2010, the Chartered Insurance Institute’s (CII) survey of 1,755 school and university students’ attitudes towards insurance stated that:

-

only 1 per cent was interested to work in the insurance sector (with 15 per cent in finance and 22 per cent in professional services, including law and accounting);

-

students regard an insurance career as dull and unethical, involving cheating rather than helping people;

-

external sources (the media, teachers, friends and family) who tend to be unaware that insurer’s risk pooling across society actually provides security influenced the students’ career choice considerably, so the students in effect know very little about insurance, which leads them to avoid this industry as a career choice;

-

communication about the value of insurance should be improved among the stakeholders to foster awareness.Footnote 4

Moreover, CII’s skill surveyFootnote 5 reported:

-

almost two-thirds of employers are suffering from talent shortages, with claims management and underwriting being urgently needed skills;

-

the majority of respondents believe that new entrants joining the industry at both the entry and leadership levels have failed to acquire sufficient skills at school or at the graduate level.

Moreover, the U.K. Border Agency has added actuaries to the shortage occupation list announced in 2011.

A PricewaterhousCoopers annual global CEO survey found that the availability of talent is critical for business growth.Footnote 6 The McKinsey & CompanyFootnote 7 survey revealed U.S. high school and college students’ limited understanding about insurance careers. Despite the availability of several quality risk management courses and jobs, the lack of collaborative effort among the insurance industry, academics and professional bodies was highlighted as a key challenge to attracting high-quality talents to the profession. A U.K. parliamentary study also recommended “promoting the insurance industry as an attractive career choice and improving the image of the industry within schools and universities”.3

All these discussions demonstrate that, on the one hand, there is frustration among college graduates because of the uncertainty surrounding the choice of insurance as a profession. On the other hand, employers (recruiters) are concerned with the shortage of skills and talents for the future of the industry. At the industry level, several factors, for example, image problem, lack of public awareness, etc., are predicted as the causes of young talents’ demotivation for the insurance profession. However, to our understanding, no scientific research had yet been conducted to find the causes of this concern. While determining the significant factors, this paper investigates why the new generation of students is reluctant to prioritise insurance as a profession. From this pilot study, the key learning points for the profession are that students are unaware of the underlying philosophy of insurance businesses, their products and of their vital role in the economic and social system. The lack of adequate research, education providers, and the shortage of study materials and inadequate marketing strategies are among the key causes of students’ reluctance to engage with the insurance profession.

The factors related to the choice of career were researched in several industries. For example, OyerFootnote 8 found that the performance of the stock market (either bull or bear) is a determinant of choice of an investment banking career for MBA students. He estimated that an MBA student graduating during a bull market and employed in investment banking earns an additional $1.5 to $5 million over the same student graduating during a bear market and employed elsewhere. Studying both domestic and international students in Australia, Jackling and KeneleyFootnote 9 found that the behavioural (intrinsic and extrinsic interests) and normative (referents) of students in terms of attitudes towards accounting influence them to choose the accounting profession. We revealed two published papers studying students’ perceptions of the insurance profession. In the U.S., the study by Cory et al.Footnote 10 found that 178 high school and college students’ pre-existing perceptions of the profession significantly influenced their career choice. Cole and McCulloughFootnote 11 recently summarised the talent gap in the U.S. insurance industry based on the concerns noted at a Griffith Education Foundation-sponsored career summit on Insurance Education, held in Atlanta, Georgia.Footnote 12 Consistent with McKinsey & Company,7 the summit identified three main obstacles, for example, insurance industry image/reputation, job-seekers’/students’ lack of awareness about insurance career options, and a lack of appropriate marketing initiatives to attract and recruit talents to the profession. The need for a coordinated strategy for overcoming these challenges was noted. We did not find any similar study for the U.K. and European insurance industries.

This research explores students’ perceptions and attitudes towards the insurance profession by identifying the key significant factors that influence their choice of an insurance career in a U.K. university. The key factors were determined via factor analysis, while a regression analysis determined the factors’ mutual influences, in an attempt to identify the students’ preferences regarding certain attributes and how these affect their career choice.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section presents a literature review with a brief description of the role and significance of insurance alongwith the factors related to career choice and the associated theories. Thereafter, the hypotheses of this study are proposed. The subsequent section describes the methodology and primary survey data. The penultimate section contains hypotheses testing, results and findings. The final section outlines the summary implications, conclusion, recommendations and direction of future research.

Literature review

The literature review describes the insurance industry’s role, significance, structure, current trends and the associated career choice theories.

Clearly, the main function of insurance is to provide individuals, businesses and society with security and financial soundness, ranging from personal accident, legal liability and business interruption to large-scale natural and human-made catastrophes.Footnote 13 Insurance works via risk pooling (i.e. sharing) at the local, regional and global levels,Footnote 14 based on the law of large numbers, that is, pricing insurable risk by increasing the number of independent policyholders.Footnote 15 Moreover, life insurance acts as a wealth transfer mechanism between the generations as part of social welfare.Footnote 16 However, the insurance business model differs from that of other financial services firms, particularly banking. Insurance companies receive premiums from their customers upfront in exchange for a promise and establish reserves in order to pay out any subsequent claims.Footnote 17 In contrast, leverage is central to the banks’ business model, so insurance companies face less risk of liquidity problems or a sudden loss of confidence,Footnote 18 and do not speculate with their earnings and capital to generate high revenue, but preserve them to demonstrate strong solvency in order to pay future claims.Footnote 19

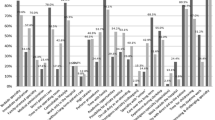

In addition to direct economic and social contribution, the insurance industry employs many individuals, thus reducing unemployment. We have analysed the data from U.K.’s Office of National Statistics and found that (see Figure 1) on average, 1.42 per cent of the total U.K. industry workforce were employed in financial services (excluding insurance and pension funds) from 1979 to 2011 inclusive, with approximately 0.56 per cent in insurance and pension funds, and 0.35 per cent in auxiliary activities.

Whereas the volatility (i.e. standard deviation) of employment in all U.K. industries from 1979 to 2011 (inclusive) is 6,750,000, it is 231,000 for financial service activities (except for insurance and pension funding), 145,000 for insurance and pension funding and 326,000 in auxiliary activities. The statistics indicate that employee turnover in insurance and pension funding is the lowest among U.K. financial services.Footnote 20

Considering their importance in the global financial sector, talented staff are vital to the insurance industry at both the national and international levels. Having noted the concerns about the talent shortage in the insurance field, we have not yet outlined the theoretical understanding behind this which is necessary for developing strategy to combat this situation. Moreover, the brain drain, where trained, skilled, experienced employees take their qualities with them when they leave, is regarded as another dimension of the skill shortage.

Theoretical framework of career choice

In the literature, career choice generally is explained by three theories, that is, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). Investigating the causes of the accounting skill shortage, Jackling and Keneley9 used TRA to understand what influence students’ choice of accounting as a career. Joshi and KuhnFootnote 21 applied TRA to investigate factors influencing career choice decisions in information systems.21 Arnold et al.Footnote 22 examined the intention to work for the U.K.’s National Health Services using TRA. In a recent study, Bagley et al.Footnote 23 investigated the factors that influence accountants’ career choice decisions using TPB and found attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control as the key factors. HuangFootnote 24 applied TPB to a group of college and university students to examine their intentions to engage in contingent employment and revealed that both attitudes and subjective norms are statistically significant in predicting intention. Lent et al.Footnote 25 presented a social cognitive framework of career development linking career interest, selection of career and performance. In addition, Cunningham et al.Footnote 26 applied social cognitive career theory to investigate students’ intention to sports and leisure career choice. However, there is no evidence to apply these theories to the choice of careers in financial services, in particular, insurance.

The TRAFootnote 27 suggests that the strength of a person’s intention predicts his/her behaviour, and that the attitude towards behaviour and subjective norms are the two principal components in determining a person’s intention.Footnote 28 From this vocational psychological point of view, a person’s subjective norm is constructed by his/her normative beliefs, weighted by the importance attributed by others to each of his/her opinions. Alternatively, attitudes help to establish personal identity, which eventually mandates a person’s thinking and indicates multiple (or patterns) rather than single behaviour. However, an occupational intention (which is a collective function of a person’s attitudes and perceived subjective norms towards the profession) are better predictors of a single behaviour. Thus, a person’s attitude to an object is thought to be related to his/her intention to perform a variety of behaviours with respect to that object.

The TRA was extended by the TPB, proposed by Ajzen,Footnote 29 and argues that behaviour requires skills, resources and opportunities (exogenous variables) and that these control attributes, which are additional to attitude and subjective norms, are not freely available.Footnote 30 Alternatively, as Madden et al.Footnote 31 concluded, “the perceived behavioural control is a significant predictor of intention after controlling for attitudes and subjective norms”. TPB measures peoples’ control beliefs and perceived behavioural control.28

Although the TPB concluded that the exogenous variables are not freely available, it failed to specify their controlling factors, particularly social attributes. Thus, SCT, proposed by Gainor and Lent,Footnote 32 can be applied to career choice, as it integrates interests, choice, performance and satisfaction to explore how career and academic interests mature, how career choices develop, and how these come into action by utilising three primary attributes (self-efficacy, outcome expectations and goals). In particular, one’s self-efficacy (which predicts, but does not cause, individuals’ belief about the skills and proficiency necessary to perform a career-related role and responsibilities) and self-evaluation of behaviour significantly influence their confidence in their goals and associated outcomes.Footnote 33 In essence, a person’s confidence increases his/her satisfaction with his/her performance.

Considering the overriding conclusion of these three theories, we argue that students choose a career with an expectation of a high income, long-term career advancement, prestige, social status, personal growth, development, a good work environment, and the opportunity for leadership and proprietorship. In the real world, this perfect match is rare, as our study assumes. Although the factors related to the availability of employment and earnings are important to the students’ career choice, these factors include perceived job satisfaction, aptitude and interest in the subject, and yet others suggest that teachers, friends, family and the media are motivating factors. Furthermore, the social values gained through working in a particular industry are crucial. We see that the SCT, in particular, added an additional personal variable “self-efficacy” to the variable “individual’s attitude” to explain that intention regarding a particular behaviour is also determined by one’s attitude towards performing career-related activities. We will utilise this theoretical framework, combined with these three theories, to analyse our survey results.

In addition to these three theories, John Holland’s Theory of Vocational Choice (TVC) is a well-known occupational choice theory that explains how individuals differ in terms of personality, interests and behaviour. The effort is to search the factors associated with person–organisational environment fit.Footnote 34 Holland’s theory suggests that a person’s behaviour is determined by the interaction between his/her personality and his/her work environment characteristics, outlining six vocational personality traits (i.e. realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising and conventional) as well as career environments.Footnote 35 Extending the fundamental proposition of TVC, ArnoldFootnote 36 suggested that people’s job satisfaction, in terms of their development, and work environment are compatible with their personalities.

In essence, individuals often compromise with the work environment and the opportunity arising from a particular career option (from a risk and reward perspective) and his/her personality, as an adjustment to Holland’s theory. We define students’ career choice in terms of the three interrelated factors, that is, environment, awareness and opportunity.

Environment represents the complex physical, economic and social factors ranging from marital status, location, religious faith, cultural identity, education and profession which make up our surroundings and, in turn, act upon our behaviour. These include the family, political, social and economic issues that the students face daily. They are in line with Fishbein and Ajzen’s Theory of Reasoned Action as discussed above. Awareness explores how the insurance profession should be promoted in education to attract young talents. Analysing Gainor and Lent’s Social Cognitive Theory we view [self]-awareness as a persistent personality dimension, since it may drive one’s interest and pattern of behaviour and ways of thinking. The variables include risk aversion, motivation, judgement and attitudes towards learning. Finally, consistently with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour, we determine opportunity as the third factor of students’ career choice. This is with the understanding that although students’ career choice is influenced by personal abilities (e.g. language skill, job experience, major etc.), choice and attitude. These should match available opportunities to be successful and demonstrate appropriate use of these personal abilities.

The hypotheses

An intuitive analysis of the industry survey results and three overarching career choice factors described above suggests that the norm of insurance and its values as a subject are not clearly understood by the students. This lack of communication ultimately diminishes the status of insurance among their career options. The literature review revealed that insurance’s intrinsic value is unlikely to attract these students, because the factors were not prominent in their understanding and career choice-related decision-making. In fact, they appear to lack confidence regarding the insurance profession.

Therefore, in line with three factors of students’ career choice as described above, we posit the following three hypotheses:

H1:

-

The environment is positively correlated with the students’ choice of the insurance profession.

H2:

-

Opportunity is negatively correlated with the students’ choice of the insurance profession.

H3:

-

Awareness is negatively correlated with the students’ choice of the insurance profession.

Questionnaire development and primary data

We surveyed 216 students at Bournemouth University; 193 students completed the questionnaire fully, and a further 10 answered over 80 per cent of the questions, giving a total sample size of 203. The students are from Europe, Asia, South America, the Middle East and Africa. There were 116 first-year business undergraduates and 87 master’s degree students from Bournemouth University (U.K.). The selection criterion for our sample reflects the fact that the selected higher educational institution does not offer insurance as a major. This is to explore non-insurance major students’ perceptions of the insurance profession. The questionnaires were distributed during an end-of-semester lecture (i.e. the second week of December 2012). Students were given up to 15 minutes to complete it.

The questionnaire was based on the three factors of career choice (environment, opportunity and awareness). (The full questionnaire is available from the authors upon request).

There were four questions related to the environmental factor. Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for the items that define this factor. The following text details some of the most relevant aspects for each item.

Q.10 explored respondents’ familiarity with several insurance designations. It is worth noting that 32 per cent of participants were completely unfamiliar with any of the seven designations listed, with most of them being completely unfamiliar with the Underwriting designation and Catastrophic Risk Modellers (see the means in Table 1). However, the variability of the responses was comparatively low (cumulative standard deviation is 1.23), the highest being 8 per cent.

Q.11 also explored the students’ familiarity with the term “insurance” as a subject or career option. The majority believe that they are somewhat familiar with insurance business through media advertisements, followed by 30 per cent through school, college, university education and background learning. In contrast, only 2 per cent claimed that they are very familiar with the insurance business through media advertisements.

Q.16 explored the respondents’ plans after graduating. The majority (51 per cent) want to get a job, and 34 per cent found it extremely unlikely that they would join a family business and were neutral about further studies, respectively.

Q.18 focuses on the understanding of basic mechanisms and the impact of insurance. Since the majority of respondents do not have any formal insurance education, the question was designed to explore their fundamental understanding of insurance’s key aim. The standard deviation of the responses shows the respondents’ confidence across all variables (Table 1). A large number of them strongly agree that insurance is a business that involves selling policies, earning lots of money as premiums and rarely compensating policyholders. Around 42 per cent somewhat agree with the statement that insurance provides security by underwriting individuals, businesses and society’s unwanted risks.

Opportunity

Two questions were related to the opportunity factor. For the opportunity factor, Table 2 is similar to Table 1 for the environmental factor; it reports means and standard deviations of items in the questionnaire. The text below presents a frequency analysis and describes how participants responded to the questions.

Q.7 explores respondent views on future career opportunities, including risk aversion. The majority (57 per cent) believe that long-term earnings strongly influence their career choice (see the item “Long-term…” in Table 2). Only a limited number of respondents ranked short-term earning as a strong influence on their career choice, indicating that the majority of respondents do not adopt a short-term view in this regard. This is somehow consistent with results from the item “Serve society” (Table 2), suggesting that many participants believe that making a contribution to society moderately influences their career choice.

In Q.19 respondents’ skills are analysed, covering their abstract thinking, intelligence, brightness, natural capacity and fast learning ability. Around 40 per cent of respondents considered themselves to have good computational and analytical skills, to be good at explaining and describing things without mathematical accuracy, and to be also good at communicating complex concepts in simple terms. The average for being good at storytelling, convincing people, negotiation and conflict resolution is among the lowest, but with higher variation (Table 2). The respondents were consistent across all five rankings for all four variables, with a low standard deviation.

Awareness

Two questions explored the awareness factor. Table 3 details means and standard deviations for the two items that specify the awareness factor.

Q.12 explored respondents’ awareness of their attraction to insurance as a subject. Only 63 students, a portion of the sample, answered this question that was presented only to those who described themselves as interested in pursuing an insurance career. A large majority of participants were “neutral” about the social recognition of the insurance profession (see item “Recognition” in Table 3). Half of the participants somewhat agreed that the current job climate has influenced them to choose a career in insurance. Also, they resulted undecided, because insurance is considered a boring subject. About the same number of participants remained undecided across all four variables, indicating that, although many choose an insurance career, they do not know why. Table 3 details these results.

The awareness factor is measured (Q.21) to study respondents’ views on promoting insurance education and establishing what would promote awareness among young talents. The majority did not recommend any specific variable as essential or high priority in promoting insurance education awareness among young talents. However, 38 per cent recommended the adoption of insurance courses in the school/college/university curriculum as a medium priority. A similar percentage of participants recommended that employment opportunities should be created in both the local and global insurance industry as a medium priority. A majority of participants recommended holding national and international insurance education and career events as a medium priority (see item “Nat. and intern. careers” in Table 3). Again, Table 3 shows that responses are consistent for all five rankings along all five variables, with a low standard deviation.

Control variables and analytical strategy

Data were also collected for 23 control variables. From these, we selected 13 that showed a better fit to the present analysis. We coded these variables according to standard conventions (details are offered in Appendix A).

We applied a mix of structural equation modelling (SEM) and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis to determine the significant factors in the students’ choice of an insurance career. The former is necessary to define the three variables, that is, environmental, opportunity and awareness as latent constructs and allows all relationships to be tested together at once. The latter method is standard when analysing how independent variables predict the dependent variable.

Data analysis and findings

Some of the variables described above need to be validated via confirmatory factor analysis before the model, containing three latent variables (environment, opportunity and awareness), is computed.Footnote 37 These procedures are described in detail in Appendix B. The analyses supported the definition of the latent variables and they can therefore be used in the analysis.

Descriptive statistics

Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for the control, dependent and independent variables. The sample seems balanced with regard to gender, with 53 per cent of the sample being female. Most of the participants were in their early 20s (mean=1.8, SD=0.81) and only 7 per cent were married (SD=0.25). The students were split between under- and post-graduates (mean=0.43, SD=0.50), and a large majority were studying finance, economics and accounting (mean=0.77, SD=0.42). Most were born in an urban area (mean=0.80, SD=0.40), and their father had a medium-high education level (mean=2.33, SD=0.99). However, parents did not work in the finance/insurance profession. Forty-two per cent were from outside the EU (SD=0.49), with an average knowledge of 1.7 written and spoken languages (SD=0.74). About half stated that they believed in God (mean=0.54, SD=0.50).

Pearson’s correlation coefficients are also shown in Table 4 for each variable. Some of the high correlations are in line with our expectations; for example, age is highly and positively correlated with post graduate students (0.60, p<0.001) as well as marital status (0.38, p<0.001); language proficiency is also positively related to age (0.28, p<0.001) and those who believe in God are more likely to be non-European (0.23, p<0.01). Also, most of the post graduate students are non-EU nationals (0.65, P<0.001). The finance profession seems to be male-dominated, as the relative correlation coefficient shows (−0.19, P<0.01). A deeper analysis is undertaken following the structural equations and regression analyses below.

Hypotheses testing

The first set of hypotheses are tested using a structural equation modelFootnote 38 and computed using the “SEM” packageFootnote 39 from R, an open-source computational software for statistics.Footnote 40 The results of the estimates of the coefficients are shown in Figure 2.

The fitness indices for this general model—that is, those defining how much the actual data reflect the theoretical model—are particularly good, showing that our data fit the theoretical model well.Footnote 41 Coefficient estimates for the structural equation model show that Hypotheses 2 and 3 are rejected, since the coefficient is either non-significant (in the case of opportunity) or marginally significant and positive. Hypothesis 1 is accepted, since the coefficient for the relation between environment and choice of career insurance is positive (β=0.22, p<0.01).

To further test the hypotheses (mostly those involving control variables), an OLS regression is computed. The coefficients and results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 shows the results of an OLS regression model that tests most of the control variables related to insurance career choice. Owing to problems related to non-normality and the distribution of residuals, this proved difficult to overcome using standard OLS procedures, so the model’s coefficients are fitted using multiple robust regressions.Footnote 42 From the regression analysis, we confirm (tentatively) what appears in the SEM (see Table 5). In addition, there is a positive, significant relation between nationality and the dependent variable of the strength of insurance as a career option. The positive coefficient (β=1.38, p<0.05) means that non-European students (also mostly postgraduates) are more likely to consider insurance as their future profession.

Summary implications, conclusion and recommendations

The aim of this research was to identify the significant factors towards students’ intentions and acceptance of a career in the insurance profession, in the light of the immanent talent gap. We discussed both industry and academic concerns about students’ lack of interest in pursuing the insurance profession. The literature suggests a number of factors ranging from the poor image of the industry to student’s limited understanding of insurance products and processes. Although several piecemeal initiatives exist, the recommendation was that the key parties involved (industry, educators and professionals) initiate a coordinated approach to counteract the talents shortage11 in the insurance profession.

The findings of our study add new dimensions to the study of how to attract talents. Unlike previous research,10 our study focuses on university students, as they may yield better information about the industry in relation to career choice and also have an interest in the issue, as they are about to enter their chosen profession. Consequently, the data we obtained are up-to-date and a better fit to this analysis.

We collected data on three overarching factors (environment, opportunity and awareness) that ultimately influence student choice of insurance as a profession. We tested three hypotheses in relation to student career choice that are based on these three factors (i.e. independent variables). The analysis employed structural equation modelling and regression analysis to test our hypotheses.

Our results show that 31 per cent of the students would consider the insurance profession at any stage of their career, 5 per cent of whom place it as their first career option, 7 per cent second, 15 per cent third and the remaining 72 per cent fourth or lower. This result is very encouraging, as the CII survey, for example, reports that 1 per cent of their respondents were interested in working in the insurance sector.4

We found that the environmental factor positively affects students’ choice of the insurance profession. This result is in line with Holland’s theory of career choice (1985) in that it highlights how the choice is affected by some social aspects that contribute to determine the person–organisation (or prospective career) fit.34 In response to Q.12 (about their attraction to the insurance profession) 47 per cent of the students remained undecided across all four variables, so there may be a lack of communication by the insurance industry, educators and professional bodies about insurance’s role and value, as several industry surveys note. The result from the SEM shows that there are two components of the environmental factor. One is “familiarity” with the concepts and the other is the “origin” of the information on insurance. These two are both contributing positively to explain the latent variable “environment”. The conformity factor analysis shows that higher familiarity with the concept and multiple sources of information contribute to defining the environment (see Appendix B). This, in turn, positively affects the choice of insurance as a professional career. Therefore, what our findings point out is that better information contributes to make this career option more interesting. The attribute “better” as it refers to information is, in this context, not generic. It refers to individuals strengthening their knowledge by getting similar (or just more) information from diverse sources (e.g. the web, parents, university) and increasing their understanding of what the insurance profession is really about. The indication that comes out from this is that the choice of career is indeed related to the quality and consistency of information that students get from different sources. This defines what can be called pre-conditions or antecedents of what is indicated in the theory of vocational choice.35

The SEM also shows that students’ awareness of the profession shows a (marginally significant) positive effect on insurance as a career choice. The regression analysis fails to support this result. Although what we found leads us to reject Hypothesis 3, it provides some limited ground for discussion. The factor “awareness” has five items that relate to the “importance of insurance in education” (see Appendix B). Although the relative hypothesis is rejected, the result is consistent with what is discussed in the paragraph above and strengthens the role of information in defining how people define their career choices. Being aware of what the insurance profession has to offer seems to contribute to defining students’ choice. What this finding adds to the discussion above is that higher education has quite a significant role in determining student career choices. This is not surprising and suggests that higher education is still key to helping students make their choices. In addition, it highlights the role of skills and confidence in career choice, consistently with the social cognition theory32 mentioned above. What can be suggested is that partnerships between industry and higher education institutions grow bigger so that university programmes provide students with more awareness of successful career alternatives that may be available.

For the remaining hypothesis, we, however, failed to prove the negative correlation between the opportunities associated with the insurance profession and their choice of an insurance career. At one stage, we thought that the incentive structure offered by the insurance industry could be an obstacle to attracting talents, but our data fail to support this assumption. This aspect certainly needs more accurate and in-depth analyses, maybe with more emphasis on the theories that inspired this element of the theoretical framework.Footnote 43

A general comment can be made on what is found in both the regression analysis and in the SEM. First, we found that information on familiarity, awareness and origin is the key to individuals in the consideration and selection of their career choices. Second, this leads to both universities and the industry working on sending clearer and stronger messages to students that they choose an economic, finance or accounting path. Third, the lack of support for Hypothesis 2—that is opportunity negatively affects insurance career choice, that is, individual “skills” and motivates for the “choice” of a career32—shows that this choice is not related to particular individual biases or prejudices over the profession (i.e. motivates for choosing a career) nor to personal capabilities, in particular mathematical and computational skills. This third element is particularly important in that it shows that there are no limits as to whom to target. Put differently, anyone can become interested in exploring insurance as a career choice. All it takes is, let us highlight this once more, clearer and stronger information. One of the theoretical implications of this finding is that the theory of reasoned action and that of planned behaviour have less explanatory power than environment and social-based theories.

On a more descriptive angle, results for Q.22 show that the majority (39 per cent) expect their initial annual salary to be £20,000–£25,000. This is close to the average gross annual salary of financial, insurance and real-estate sector employees in the U.K.Footnote 44 To our understanding, this article is the first to conduct a scientific analysis of the influential factors on university business students’ choice of an insurance career. The framework developed and the factors identified provide a basis for further research on students’ perceptions of the insurance profession as a career choice.

Regarding the control variables, we only find a positive, significant relation between nationality and students’ choice of insurance as a career option, in line with the general market assumption and industry reports/surveys. We, however, expected more control variables (e.g. a finance major) to be significant. These results are preliminary, so more refined measures and an increased sample size will expand our findings.Footnote 45

This paper points to the importance of students being exposed to insurance processes and products. This ensures better recruitment of talents, expands the recruitment basis and creates more informed customers.Footnote 46 One aspect that can be derived from the findings discussed in the paper is the point of contact between the profession and the students surveyed. The study considers students as potential workers in the insurance industry, and evaluates the likelihood that they would consider that option in their professional careers. However, even if they are not willing to consider that option, they will be (they are) in contact with some elements of the insurance business. All of them are customers, have dealt with insurance-related products in the past and/or will in the future. The fact that most students may not know much about career opportunities, may not be interested or may not be too sure about jobs available does not necessarily mean that they do not use insurance-related products. In fact, results from Q.10 suggest that participants are not fully aware of career options (Table 1), but responses to Q.18 show that they know what insurance is about (Table 1). What was found through Q.18 may be matched with Q.19 (Table 2), which highlights how confident participants are in their mathematical and computational capabilities. From this, we may find a first and indirect support to the claim that, even if they are not interested in a career in the insurance business, students may still become good customers. The understanding of insurance-related products is key to customers, and this business relationship is strengthened by math skills and a fair knowledge of what is offered in the market. Of course, this is but a preliminary result and it was not the focus of the current study. However, given its importance, future research may well explore the motives and the likelihood that business students become good customers.

This study contributes to the ongoing debate on the talent shortage in the global insurance industry. Unlike previous studies, the students in our sample are majoring in mainstream subjects (rather than insurance) and some (categorised as international) have no idea about the broader nature of insurance business, including insurance designations. This study may help the insurance industry, educators and professional bodies to target the appropriate market to attract and develop talents. Moreover, the significant factors identified in this study can provide the necessary information for developing a strategy to educate and retain talents by addressing their perceptions of the insurance profession. The campaign to popularise the insurance profession is already strong; for example, the Griffith Foundation’s recent insurance career fair in the U.S., the CII initiative through the web portal “Discover Risk”, The Geneva Association’s recent research publication that compares insurance with banking (in the light of the recent financial crisis) all positively demonstrate insurance’s significance to the external audience, ultimately helping to attract talents to this area. Moreover, the AXA Research Fund,Footnote 47 The Geneva Association,Footnote 48 the Griffith Foundation,Footnote 49 along with several professional bodies’ scholarships and grants are certainly attracting students to join and study the insurance field.Footnote 50

Since our analysis suggests that students’ awareness negatively affects their choice of an insurance career, closer engagement with university students is recommended to highlight their core understanding of insurance, the broader scope of insurance education and professional routes, along with the opportunities available. Moreover, the industry needs to offer internships and work placements to college/university students.

This pilot study is the first step towards collecting and analysing data on student preferences regarding the insurance profession. It suffers from several limitations. We offer a list of the most significant:

-

1

The small sample size is an issue, and similar studies with a larger representative sample would secure more robust results.

-

2

We assume that students gave honest answers to the survey, but some may have responded superficially, without enough thinking or attention. Future researchers may find ways to detect biased replies/inconsistencies within questionnaire responses. More effective manipulation checks may help.

-

3

With the application of standard statistical techniques we concluded that students’ nationality plays a role, among several other factors. However, this aspect needs careful examination to provide a better understanding as to why nationality is a factor.

These limitations may be counteracted in future studies. As insurance is not categorised as a mainstream academic subject, unlike accounting, management and finance, the number of students majoring in insurance may always be an issue. Moreover, we found a positive correlation between the environment and students’ choice of the insurance career, as the recruitment/employment of students to the profession is seasonally driven. Fortunately, with the growing global relevance of insurance following the 2008 financial crisis, there will be greater scope to attract and develop talents to this area.

Students in our sample are starting their first semester of undergraduate studies. They will be taught a few insurance topics and will have the opportunity to attend insurance career events/presentations by a professional insurance body (e.g. the CII), so it would be interesting to assess how attending these elements influence their perceptions and career choice. A pre-semester study can be matched with a post-semester study providing a measure of how effective that type of exposure has been. Another interesting follow-up study may focus on whether the rapid growth of microinsurance in developing countries attracts international students more/better than the developed countries, for example, countries in Western Europe and North America.

Notes

A summary report of the event is available at www.griffithfoundation.org.

In order to understand the nature and significance of the insurance industry, interested readers may consult the studies of Liedtke (2003); Swiss Re (1990, 2012); Thomas (2007); Skipper (1997) and Outreville (1990).

Interested readers can find U.S. data for insurance employment trend on the homepage of Bureau of Labour Statistics at www.bls.gov.

Proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975); Ajzen and Fishbein (1980).

Ajzen (1991, 1998).

SEM; Greene (1993).

Chi-squared=382.26 [d.f.=283, p<0.001], RMSEA=0.04, CFI=0.93, SRMR=0.07.

E.g. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980).

Using the data available from the U.K. Office of National Statistics, the authors estimate that, between 1995 and 2011, the average annual gross salary for the financial, insurance and real estate sector employees was around £30,000, which is £7,000 higher than the U.K. average for all employees irrespective of sectors.

We acknowledge and thank one of the anonymous reviewers for highlighting this point.

The French AXA Group funds research into preventing risk in terms of environmental, life and economic issues (www.axa-research.org).

The Geneva Association offers several scholarships including the SHIN Research Excellence Award in association with the International Insurance Society, the Ernst Meyer Prize and research grants to foster high-quality insurance research and education.

The Griffith Foundation provides a few scholarships to enable students to study insurance and risk management at college and university (www.griffithfoundation.org).

See www.egrie.org;www.aria.org for details about insurance research and education scholarships.

References

Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Ajzen, I. (1991) ‘The theory of planned behaviour’, Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (1998) Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour, Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press.

Armitage, C.J. and Conner, M. (2001) ‘Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review’, British Journal of Social Psychology 40 (4): 471–499.

Arnold, J. (2004) ‘The congruence problem in John Holland’s theory of vocational decisions’, Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology 77 (1): 95–113.

Arnold, J., Clarke, J.L., Coombs, C., Wilkinson, A., Park, J. and Preston, D. (2006) ‘How well can the theory of planned behaviour account for occupational inventions’, Journal of Vocational Behaviour 69 (3): 374–390.

Bagley, P.L., Dalton, D. and Ortegren, M. (2012) ‘The factors that affect accountants’ decisions to seek careers with big 4 vs. non-big 4 accounting firms’, Accounting Horizons 26 (2): 239–264.

Barth, M.M. (1999) ‘Applying the law of large numbers to P&C risk-based capital’, Journal of Insurance Regulation 17 (4): 438–477.

Chartered Insurance Institute (2010) Insuring a Better Future—How to Attract the Best Students into Insurance, Policy and Public Affairs, London, U.K.: Chartered Insurance Institute.

Chartered Insurance Institute (2012) “Mind the gap: Skills report 2012”, London, United Kingdom: The Personal Finance Society, from www.cii.co.uk.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G. and Aiken, L.S. (2003) Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 3rd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cole, C.C. and McCullough, K.A. (2012) ‘The insurance industry’s talent gap and where we go from here’, Risk Management and Insurance Review 15 (1): 107–116.

Conner, M. and Arbitrage, C.A. (1998) ‘Extending the theory of planned behaviour: A review and avenues for further research’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28 (15): 1429–1464.

Cory, S.N., Kerr, D. and Todd, J.D. (2007) ‘Student perception of the insurance profession’, Risk Management and Insurance Review 10 (1): 121–136.

Cunningham, G.B., Jennifer, B., Sartore, M.L., Michael, S. and Fink, J.S. (2005) ‘The application of social cognitive career theory to sport and leisure career choices’, Journal of Career Developments 32 (2): 122–138.

DeVellis, R.F. (2012) Scale Development. Theory and Applications. Applied Social Research Methods, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fischer, T. (2007) ‘A law of large number approach to valuation in life insurance’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 40 (1): 35–57.

Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fox, J. (2006) ‘Structural equation modelling with the SEM package in R’, Structural Equation Modelling 13 (3): 465–486.

Furnham, A. (2001) ‘Vocational preference and P-O.Fit: Reflections on Holland’s theory of vocational choice’, Applied Psychology: An International Review 50 (1): 5–29.

Gainor, K.A. and Lent, R.W. (1998) ‘Social cognitive expectations and racial identity attitudes in predicting the math choice intentions of black college students’, Journal of Counselling Psychology 45 (4): 403–413.

Greene, W.H. (1993) Econometric Analysis, 2nd edn. New York: Macmillan.

Hawkins, R.M.F. (1992) ‘Self-efficacy: A predictor but not a cause of behaviour’, Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychology 23 (4): 251–256.

HM Treasury (2009) “Vision for the insurance industry in 2020: A report from the insurance industry working group”, Office of Public Sector Information, London: United Kingdom, fromwww.hm-treasury.gov.uk.

Holland, J.L. (1985) Making Vocational Choices, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Huang, J.-T. (2011) ‘Application of planned behaviour theory to account for college students’ occupational intention in contingent employment’, The Career Development Quarterly 59 (5): 455–466.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors (2003) “Insurance core principles and methodology”, Principles No. 1, Basel, Switzerland, from www.iaisweb.org.

Jackling, B. and Keneley, M. (2009) ‘Influences on the supply of accounting graduates in Australia: A focus on international students’, Accounting and Finance 49 (1): 141–159.

Joshi, K.D. and Kuhn, K. (2011) ‘What determines interest in an IS career? An application of the theory of reasoned action’, Communications of the Association for Information Systems 29 (8): 133–158.

Kline, R.B. (2005) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Knights, D. and Vurdubaki, T. (1993) ‘Calculations of risk—Towards an understanding of insurance as a moral and political technology’, Accounting, Organisation and Society 18 (7/8): 729–764.

Krvavych, Y. and Sherris, M. (2006) ‘Enhancing insurer value through reinsurance optimization.’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 38 (3): 495–517.

Lent, R.W., Brown, S.D. and Hackett, G. (1994) ‘Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice and performance’, Journal of Vocational behaviour 45 (1): 79–122.

Liedtke, P.M. (2003) ‘Insurance misunderstood’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 28 (3): 369–373.

Liedtke, P.M. (2007) ‘What’s insurance to a modern economy?’ The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 32 (2): 211–221.

Madden, T.J., Ellen, P.S. and Ajzen, I. (1992) ‘A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 18: 3–9.

McKinsey & Company (2010) “Building a talent magnet how the property and casualty industry can solve its people needs”, Financial Services Practice, from www.mckinsey.com.

Outreville, J.F. (1990) ‘The economic significance of insurance markets in developing countries’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 57 (3): 487–498.

Oyer, P. (2008) ‘The making of an investment banker: Stock market shocks, career choice and lifetime income’, The Journal of Finance 63 (6): 2601–2628.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2010) “Talent Mobility 2020—The next generation of international assignments”, PricewaterhouseCoopers, from www.pwc.com.

Rymaszewski, P., Schmeiser, H. and Wagner, J. (2012) ‘Under what conditions is an insurance guarantee fund beneficial for policyholders’, Journal of Risk and Insurance 79 (3): 785–815.

Skipper, Jr., H. (1997) Foreign Insurers in Emerging Markets: Issues and Concerns, Center for Risk Management and Insurance, Occasional Paper 97–2, Georgia State University.

Stahel, W.R. (2003) ‘The role of insurability and insurance’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 28 (3): 374–381.

Swiss Re (2012) “Global insurance review 2012 and outlook 2013/14”, Economic Research and Consulting, Zurich, Switzerland: Swiss Reinsurance Company, from www.swissre.com.

Tarique, I. and Schuler, R.S. (2010) ‘Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research’, Journal of World Business 45 (2): 122–133.

The R Development Core Team (2012) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Thomas, R.G. (2007) ‘Some novel perspectives on risk classification’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 32 (1): 105–132.

Ward, R (2007) “Looking ahead to a positive future for insurance”, Lloyd’s speech at Xchanging Conference, London, United Kingdom, from www.lloyds.com.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Luke Savage, Director of Finance of the Lloyd’s of London, Caspar Bartington of the Chartered Insurance Institute and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts. The authors would like to also thank the students for participating in the survey. The views expressed in this study are the authors’ own and not the views of their affiliated institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Correction

The AOP version of this article has been amended to remove the Appendix citation included in error.

Appendices

Appendix A

Control variables

Q.1 asked about the students’ nationality and it was coded as a dummy variable with 58 per cent of participants being European (coded 0) and 42 per cent non-European (Asian, African, Arab and American, coded 1).

The second variable (Q.3) found that 80 per cent were from an urban area, with the remaining 20 per cent from villages. The variable was dummy coded too with 1 for urban area, 0 otherwise.

The third (Q.4, Q.5) found that 9 per cent of the respondents’ fathers and 4 per cent of their mothers are engaged in the insurance profession (again, dummy coded).

The fourth (Q.6) found that 54 per cent believe in God (coded 1) and the remaining 46 per cent do not (coded 0).

The fifth (Q.26) found that 47 per cent are financing their current studies via bank loan, 71 per cent via their own resources, 38 per cent via their parents/family wealth, and 51 per cent via a combination of their own and their parents/family wealth (this was coded as a categorical variable, so that every choice is a dummy variable).

The sixth (Q.28) found that 13 per cent are only children, 42 per cent have one sibling, 25 per cent have two, 4 per cent have three, 8 per cent have four and 7 per cent have five or more. This variable was coded with the number of children (1 single child, 2 if two siblings, etc.).

The seventh (Q.13) found that 53 per cent are female (coded 1) and the remaining 43 per cent are male (coded 0).

The eighth (Q.31) found that 9 per cent of the respondents’ fathers have a PhD degree, 41 per cent are university graduates, 24 per cent are college graduates/hold a professional diploma and 26 per cent are educated to secondary level. This is coded 1 for the lowest degree, 2 for the second lowest, and so on.

The ninth (Q.2) found that around 9 per cent can speak more than three languages and 13 per cent can speak and write more than two. For the coding, numbers of languages spoken were taken as the values of the variable.

The tenth (Q.14) found that 57 per cent are undergraduates (coded 0) and the remaining 43 per cent are postgraduates (coded 1).

The eleventh (Q.15) found that 77 per cent are majoring in finance, economics and accounting (coded 1), and the remainder in management, marketing and law (coded 0).

The twelfth (Q.27) found that 40 per cent of the respondents were under 20 (coded 1), 43 per cent between 20 and 25 (coded 2), 13 per cent between 25 and 30 (coded 3) and the remainder between 30 and 40 (coded 4).

The thirteenth (Q.29) found that 93 per cent were unmarried (coded 1) and 7 per cent married (coded 0).

Appendix B

Confirmatory factor analyses

The first variable consists of four components - familiarity, origin, career, and knowledge – made up, respectively, of seven, five, four, and four items (see above). The CFA model for familiarity shows a good fit, with χ2 = 8.69 [df = 8, p = 0.36], RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02, and supports a one-factor structure for the measure. The reliability coefficient for the variable familiarity is 0.90 (Nunnally, 1978).

The second variable is origin and the CFA fits five items with χ2 = 2.2 [df = 5, p = 0.83], RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02. The Cronbach’s α for this component is 0.67. The measure is reliable and can be used in the analysis. Career has four items and the CFA shows the following fitness indices: χ2 = 4.17 [df = 2, p = 0.12], RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.03. The α for this measure is particularly low, at 0.55. Despite the good results from the fitness indices in the CFA, the measure cannot be used because the reliability coefficient falls below the threshold of 0.60 (DeVellis, 2012). The fourth measure that forms the variable environment is knowledge. The CFA results show a good fit for the four-item model: χ2 = 0.87 [df = 1, p = 0.35], RMSEA = 0.00, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.01. Again, we have an extremely low measure here for the Cronbach’s α (0.48). This measure, unfortunately, does not match the minimum requirements for reliability and validity, and hence is excluded from our study.

The model for the variable environment is obtained with a CFA that combines the two components above. The fitness indices for that model are as follows: χ2 = 160.96 [df = 95, p < 0.001], RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.07. These values indicate that the model shows a good fit, and hence is reliable and accurate. We can disregard the significant p-value because the ratio of χ2 on the degrees of freedom is below 3.0 (Byrne, 1989). The values for the coefficients are discussed below (see also Figure 1).

The second latent variable that we calculated is opportunity that derives from two components: choice and skills (see above). We used a CFA to check whether these two variables explain the emergence of the latent variables and found good fitness indices for the two-factor model: χ2 = 34.07 [df = 17, p = 0.008], RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.08. The reliability coefficient α is 0.61, showing that there is some ground for accepting this measure (DeVellis, 2012).

A third latent variable (awareness) is defined by five items (the promotion of insurance in education). CFA shows that there is a good fitness between the theoretical model and the data: χ2 = 8.51[df = 5, p = 0.13], RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.03. The Cronbach’s alpha for the variable shows good reliability of 0.76.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Acharyya, M., Secchi, D. Why Choose an Insurance Career? A Pilot Study of University Students’ Preferences Regarding the Insurance Profession. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 40, 108–130 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2013.33

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2013.33