Abstract

As of 21 December 2012, the use of gender as an insurance rating category is prohibited in the EU. Any remaining pricing disparities between men and women will now be traced back to the reasonable pricing of characteristics that happen to differ between the groups or to the pricing of characteristics that differ between sexes in a way that proxies for gender. Using data from an automobile insurer, we analyse how the standard industry approach of simply omitting gender from the pricing formula, which allows for proxy effects, differs from the benchmark for what prices would look like if direct gender effects were removed and other variables did not adjust as proxies. We find that the standard industry approach will likely be influenced by proxy effects for younger and older drivers. Our method can simply be applied to almost any setting where a regulator is considering a uniform pricing reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, ABI (2008) and Crocker and Snow (2013).

For example, Harrington and Doerpinghaus (1993).

For example, Oxera (2011c).

A comprehensive analysis of asymmetric information in the German car insurance market can be found in Spindler et al. (2014).

SAI (2004) and SAI (2011).

In an earlier draft of this paper, we also made the analysis for comprehensive and collision coverage. The results were qualitatively the same.

We are very grateful to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the simulation approach.

For a survey article on hedonic price functions, refer to Nesheim (2006).

References

ABI (2008) The role of risk classification in insurance, ABI Research Paper No. 11, London: Association of British Insurers.

ABI (2010) The use of gender in insurance pricing, ABI Research Paper No. 24, London: Association of British Insurers.

AIRAC (1987) Unisex Auto Insurance Rating: How auto insurance premiums in Montana changed after the elimination of sex and marital status as rating factors, Oak Brook, IL: All-Industry Research Advisory Council.

Crocker, K.J. and Snow, A. (2013) ‘The theory of risk classification’ in G. Dionne (ed.) Handbook of Insurance, New York/Heidelberg/Dordrecht/London: Springer, pp. 281–313.

Dahlby, B.G. (1992) ‘Adverse selection and statistical discrimination: An analysis of Canadian automobile insurance’, in G. Dionne and S.E. Harrington (eds) Foundations of Insurance Economics, Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic, pp. 376–385.

Dionne, G. and Vanasse, C. (1992) ‘Automobile insurance ratemaking in the presence of asymmetrical information’, Journal of Applied Econometrics 7 (2): 149–165.

EC (2011) ‘Guidelines on the application of Council Directive 2004/113/EC to insurance, in the light of the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in Case C-236/09 (Test-Achats)’, Official Journal of the European Union, 54.

GDV (2012) Statistisches Taschenbuch der Versicherungswirtschaft 2012, Berlin: Gesamtverband der Deutschen Versicherungswirtschaft.

Harrington, S.E. and Doerpinghaus, H.I. (1993) ‘The economics and politics of automobile insurance rate classification’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 60 (1): 59–84.

Hemenway, D. (1990) ‘Propitious selection’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 105 (4): 1063–1069.

Nesheim, L. (2006) Hedonic price functions, Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice Working Paper CWP18/06, The Institute for Fiscal Studies, Department of Economics, University College of London.

Neudeck, W. and Podczeck, K. (1996) ‘Adverse selection and regulation in health insurance markets’, Journal of Health Economics 15 (4): 387–408.

Ornelas, A., Guillén, M. and Alcañiz, M. (2013) ‘Implications of unisex assumptions in the analysis of longevity for insurance portfolios’, in M.Á. Fernández-Izquierdo, M.J. Muñoz-Torres and R. León (eds) Modeling and Simulation in Engineering, Economics, and Management, Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 99–107.

Oxera (2011a) Gender and insurance: unintended consequences of unisex insurance pricing, Agenda—Advancing economics in business, March.

Oxera (2011b) Gender and insurance: impact on EU consumers of a ban on the use of gender, Agenda—Advancing economics in business, December.

Oxera (2011c) The impact of a ban on the use of gender in insurance, December.

Polborn, M.K., Hoy, M. and Sadanand, A. (2006) ‘Advantageous effects of regulatory adverse selection in the life insurance market’, The Economic Journal 116 (508): 327–354.

Pope, D.G. and Sydnor, J.R. (2011) ‘Implementing anti-discrimination policies in statistical profiling models’, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3 (3): 206–231.

Puelz, R. and Kemmsies, W. (1993) ‘Implications for unisex statutes and risk-pooling: The costs of gender and underwriting attributes in the automobile insurance market’, Journal of Regulatory Economics 5 (3): 289–301.

Riedel, O. and Münch, C. (2005) ‘Zur Bedeutung der sekundären Prämiendifferenzierung bei Unisex-Tarifen in der Krankenversicherung’, Zeitschrift für die gesamte Versicherungswissenschaft 94 (3): 457–478.

Riedel, O. (2006) ‘Unisex tariffs in health insurance’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 31 (2): 233–244.

SAI (2004) The draft EU Directive on equal insurance premiums for men and women, Dublin: Society of Actuaries in Ireland, from web.actuaries.ie.

SAI (2011) European Court of Justice ruling—profound implications for insurance industry and consumers, press release, Dublin: Society of Actuaries in Ireland, from web.actuaries.ie/.

Sass, J. and Seifried, F.T. (2014) ‘Insurance markets and unisex tariffs: is the European Court of Justice improving or destroying welfare?’ Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 2014 (3): 228–254.

Schmeiser, H., Störmer, T. and Wagner, J. (2014) ‘Unisex insurance pricing: Consumers’ perception and market implications’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 39 (2): 322–350.

Siegelman, P. (2004) ‘Adverse selection in insurance markets: An exaggerated threat’, The Yale Law Journal 113 (6): 1223–1281.

Spindler, M., Winter, J. and Hagmayer, S. (2014) ‘Asymmetric information in the market for automobile insurance: Evidence from Germany’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 81 (4): 781–801.

Thiery, Y. and Van Schoubroeck, C. (2006) ‘Fairness and equality in insurance classification’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 31 (2): 190–211.

Thomas, R.G. (2007) ‘Some novel perspectives on risk classification’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 32 (1): 105–132.

Wallace, F.K. (1984) ‘Unisex automobile rating: The Michigan experience’, Journal of Insurance Regulation 3 (2): 127–139.

Acknowledgements

We thank Frederick Schlagenhaft and two anonymous referees for their comments. Moreover, we are grateful to Andreas Richter for invaluable discussions and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

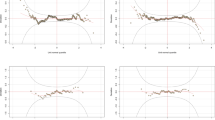

Kernel density plots

Poisson and claims regression

Simulation

Explanation of variables:

- x1, x2, x3, x5::

-

uniformly distributed on the interval [0, 1) and correlated with each other

- x4, x6::

-

uniformly distributed on the interval [0, 1) and correlated with each other

- x7::

-

uniformly distributed on the interval [0, 1)

- x2x3::

-

interaction term x2∗x3

- x3x4::

-

interaction term x3∗x4

- x2x6::

-

interaction term x2∗x6

- y::

-

is the “claims” variable, which is a function of the variables x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x3x4, x2x3 and a uniformly distributed error term

- y_hat::

-

represents the insurer’s predicted premium

Explanation of the simulation approach:

-

See Table A3 for the outputs of the linear models and Table A4 for the outputs of the non-linear models.

Table A3 Extended simulation—linear model Table A4 Extended simulation—non-linear model -

Column (1): Regression of y on all variables that are generating y.

-

Column (2): Regression the insurer presumably does; a subset of the true data generating variables (x1, x2, x3) plus the additional variable x6 which is correlated with x4 and the additional uncorrelated variable x7.

-

Column (3): Estimation of the insurers pricing formula including the discriminating variable, this regression resembles the full model.

-

Column (4): Estimation of the omitted model on the insurers prices y_hat.

-

Column (5): Estimation of the omitted model on the true claims y.

-

Columns (6)–(9): Repetition of columns (2)–(5), but the “insurer” additionally includes the interaction term x2x6.

Key findings

-

The results of the simple simulation (see Table 3 in the paper) also hold for a more general setting.

-

From the comparison of columns (4) and (5) as well as columns (8) and (9) one can see that coefficients are identical, only standard errors are tighter for the regression using “premium” as dependent variable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aseervatham, V., Lex, C. & Spindler, M. How Do Unisex Rating Regulations Affect Gender Differences in Insurance Premiums?. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 41, 128–160 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2015.22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2015.22