Abstract

We analyse the welfare effect of governmental regulation for individuals who consider anticipated regret in their decision-making process. Although governmental policies by directing choice, distort individual decisions in the private market, they can alleviate individuals’ pain associated with the feeling of regret. We analyse this trade-off and provide conditions under which the implied reduction of regret justifies regulation. Furthermore, we demonstrate our findings on tax deduction for non-insured losses, a well-studied social policy in insurance. Last, we consider heterogenous individuals and alternative social welfare functions and show that our results hold in these extended settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regulation of competitive markets is typically justified by inefficiencies arising from externalities or asymmetric information problems. A different line of reasoning argues that individuals make certain decisions that are not in their own best interests, for example, caused by problems of self-control or incorrect beliefs. This gives rise to the role of the government as a paternalist. By correcting these decisions, the government increases welfare for those individuals.Footnote 1 The nature and degree of paternalism can take various forms, from soft paternalism such as providing information, specifying default rules,Footnote 2 or taxation,Footnote 3 up to hard paternalism such as limiting or even forcing choices.Footnote 4 Camerer et al. Footnote 5 propose asymmetric paternalism with large benefits for boundedly rational consumers and little costs to fully rational consumers, for example, default rules that can easily be overruled. Glaeser,Footnote 6 on the other hand, argues that consumers might face stronger incentives than governments do to correct those errors and that millions of consumers might be less prone to persuasion by private firms than a few government bureaucrats. Sandroni and SquintaniFootnote 7 also urge to be cautious about the paternalistic rationale for governmental intervention. They show that the asymmetric information rationale for compulsory insurance might be eroded by the existence of individuals who have overconfident beliefs.

In this paper, we examine a different reason for governments to direct individuals’ choice—either directly by restricting the choice set or indirectly by providing incentives for specific choices. Our rationale is built on the assumption that individuals’ welfare depends on foregone alternative choices, that is, choices that individuals decided not to choose but could have chosen. This dependence on foregone alternative choices arises from the feeling of regret or self-blame if some foregone alternative choice would have yielded a superior outcome. Governmental intervention in markets by means of directing choice might either change the set of foregone alternative decisions the individual could have chosen from freely and/or the difference to wealth levels implied by foregone alternative decisions. This effect can be beneficial for individuals if they associate a cost with the feeling of regret or self-blame. Since they are either directly or indirectly forced by the government to certain decisions, individuals feel no regret or self-blame for those decisions because they were not available to them for choice. Directing individuals’ choices in that way thus reduces the feeling of regret and thereby increases their welfare.Footnote 8 However, the partial imposition of, or provision, of incentives for certain decisions potentially implies a discretionary effect of individuals’ decisions in the private market and thereby reduces individual welfare.

In this paper, we examine this trade-off of governmental intervention under individual preferences that take into account the feeling of regret. In the general model, we assume that the government optimises the social welfare function by setting a policy taking into account that a representative regret-sensitive agent subsequently makes a decision in the private market. We examine the effect of the government’s policy on social welfare and provide conditions under which the optimal governmental intervention for a regret-sensitive agent differs from the one for an agent who is not regret sensitive. We then apply our results to the tax policy of allowing individuals to deduct some portion of their privately uninsured losses from their taxable income. We show that such tax policy is optimal for regret-sensitive individuals despite its discretionary effect in the private market. This result holds even in a heterogeneous population as long as the latter contains some regret-sensitive individuals. If the government considers regret as a bias that distorts individuals’ decisions, then a tax policy could even correct the impact of this bias.

There is much empirical evidence of both individuals experiencing regret and the anticipation of regret influencing individual decision-making.Footnote 9 We refer to ZeelenbergFootnote 10 who reviews the evidence from these and other studies in which regret is made salient to individuals at the time of choice and from studies in which the uncertainty resolution of alternative choices is manipulated. More recently, Zeelenberg and PietersFootnote 11 compare two lotteries in the Netherlands, a regular state lottery and a postcode lottery in which the postcode is the ticket number. In the latter lottery, individuals who decide not to play the lottery thus receive feedback about whether they would have won had they played the lottery. They conduct different studies which all confirm that this feedback causes regret and changes the decision whether to play the lottery.Footnote 12 Filiz-Ozbay and OzbayFootnote 13 conduct first price auction experiments and show that individuals experience loser regret—the regret a losing bidder experiences if the winning bid is revealed—which leads them to overbid. Finally, Camille et al. Footnote 14 and Coricelli et al. Footnote 15 find that the medial orbitofrontal cortex plays a central role in mediating the feeling of regret. In the experimental study of Camille et al. 14 normal subjects reacted to the experience of regret and chose to minimise it in the future while patients with orbitofrontal cortex lesions did not report regret or anticipated negative consequences from their choices. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Coricelli et al. 15 found enhanced activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex in response to an increase in regret.

There is also empirical evidence that responsibility for choices and the feeling of regret are positively related.Footnote 16 That is, if some foregone decision would have implied a superior outcome, individuals who personally make a decision experience more regret than individuals on whom that same decision is imposed. Botti and McGillFootnote 17 also examine the effect of personal vs other-made choice on subjects’ satisfaction and emphasise the importance of perceived personal responsibility of choice. They confirm the evidence that only subjects who feel personally responsible for their choice experienced both greater self-credit and self-blame than subjects on whom the choice was imposed. Iyengar and LepperFootnote 18 show that subjects facing a larger choice set reported that they are more dissatisfied and have more regret about the choices they have made than subjects facing a more limited choice set.Footnote 19 These empirical findings support our reasoning in this paper that governmental regulation, by taking on responsibility for certain decisions, partially relieves individuals of that choice responsibility and thereby of subsequent potential regret.

Zeelenberg and PietersFootnote 20 propose various strategies for individuals to self-regulate their feeling of regret including transferring decision responsibility to others, for example, to financial advisors or to other experts. Even though delegating a decision might reduce the feeling of regret for that decision, the delegation decision itself might induce regret. Although this is not an issue in our context of governmental enforcement, such regulation can create discretionary effects on individual decision-making in the private market. This is the trade-off we are exploring in this paper.

BellFootnote 21 and Loomes and SugdenFootnote 22 propose modified forms of the utility function which incorporate regret. They show that anticipated regret can help explain empirically observed violations of expected utility theory, for example, the Allais paradox, the common ratio effect, or simultaneous gambling and insuring. SugdenFootnote 23 and QuigginFootnote 24 provide an axiomatic foundation for representing regret preferences by the expected value of a utility function which depends only on the realised level of wealth and the level of wealth the individual could have achieved with the foregone best alternative, that is, with the foregone alternative that would have led to the highest level of wealth. This representation of regret preferences has then been applied in various settings. Braun and MuermannFootnote 25 and Muermann et al. Footnote 26 examine the demand for insurance and portfolio allocation. They show that regret leads individuals to hedge their bets by avoiding extreme decisions. Moreover, regret can help explain the disposition effect, the tendency of investors to sell winning assets too early and hold on to losing assets.Footnote 27 Gollier and SalaniéFootnote 28 consider an Arrow-Debreu economy and show that regret implies a preference for skewed distributions as observed in horse race betting and national lotteries. We contribute to this literature by analysing the benefit of governmental intervention with regard to reducing individuals’ pain associated with regret, while taking into account its discretionary effect on individuals’ decisions in the private market.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section we specify individuals’ preferences taking into account the feeling of anticipatory regret and examine the trade-off of governmental intervention in a general model. In the subsequent section, we apply the general model to income tax deduction of non-insured losses. In the penultimate section, we extend our setting by discussing alternative social welfare functions and by considering heterogeneous individuals. We conclude in the final section.

Preferences and general setup

We assume that preferences are represented by the maximisation of expected utility with respect to a two-attribute value function v=v(w, w max) which depends on the realised level of wealth, w, and the maximum level of wealth, w max, the individual could have achieved by the foregone best alternative in the realised state of nature. Ex post, the individual thus regrets that he did not make the decision that would have led to the wealth level w max. Ex ante, the individual anticipates his ex post feeling of regret, which he takes into account in his decision-making process.

Representing this anticipatory feeling of regret by the two-attribute value function v=v(w,w max) is justified by the axiomatic foundation of Sugden23 and Quiggin.24 They formulate axioms under which the representative value function depends only on the realised level of wealth and the maximum level of wealth the individual could have obtained in each realised state of the world. We apply the following functional form

for some Bernoulli utility function u and function g which is based on Bell21 and Braun and Muermann.25 Regret thus depends on the difference between the utility of realised wealth and the utility of wealth under the foregone best alternative. We assume that the utility function u is strictly increasing and strictly concave, that is, u′>0 and u″<0. For the second term that accounts for regret, we assume g(0)=0, g′>0, and g″>0. The convexity of g implies that the marginal utility of wealth is increasing in the wealth level implied by the foregone best alternative. This condition is consistent with regret preferences explaining observed violations of expected utility theoryFootnote 29 and is supported by empirical evidence.Footnote 30 The constant k⩾0 measures the relative importance of regret. If k=0, then the individual is not sensitive to the feeling of regret and maximises expected utility.

Let wealth  be a continuously differentiable function of the individual’s choice q∈

be a continuously differentiable function of the individual’s choice q∈ , the governmental policy t∈

, the governmental policy t∈ , and the state variable

, and the state variable  . We assume that the choice set

. We assume that the choice set  and the policy set

and the policy set  are compact subsets of the real line and that the state variable is a real-valued random variable. For example, in the next section the governmental policy t is the tax rate at which individuals are allowed to deduct the non-insured portion of losses and the individual’s choice q is the level of insurance coverage purchased in the private insurance market. A different application of this setting is governmental intervention in defined contribution (DC) retirement plans by means of mandating a minimum return guarantee t on DC plan participants’ portfolio allocation q.Footnote 31

are compact subsets of the real line and that the state variable is a real-valued random variable. For example, in the next section the governmental policy t is the tax rate at which individuals are allowed to deduct the non-insured portion of losses and the individual’s choice q is the level of insurance coverage purchased in the private insurance market. A different application of this setting is governmental intervention in defined contribution (DC) retirement plans by means of mandating a minimum return guarantee t on DC plan participants’ portfolio allocation q.Footnote 31

We consider the following sequence of events.

Time 0 The government sets the policy t.

Time 1 The individual chooses q.

Time 2 The state variable realises and the individual consumes his wealth.

We solve for the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium by backward induction which implies the following optimisation problems.

Time 2 For a given policy t and realised state of nature  , the corresponding foregone best alternative, q

max(t, x), is given by

, the corresponding foregone best alternative, q

max(t, x), is given by

For inner solutions, the first-order condition is given by

for all t and x. The implied maximum level of wealth the individual could have obtained is therefore w max=w(q max(t, x), t, x).

Time 1 Given the policy t, the individual chooses q to maximise his expected utility according to the utility function v. Since the individual has no influence on the choice of the governmental policy t, he only regrets towards his own decision q.Footnote 32 The optimal choice q is then given by the solution of the following maximisation problem:

To simplify notation, we omit the arguments of wealth in the following analyses.

The corresponding first-order condition is

Let q

k

∗=q

k

∗(t) denote the inner solution to Eq. (4). In the following, we denote final wealth under the decision q

k

∗ by  .Footnote 33

.Footnote 33

Time 0 At Time 0, the government sets the policy t considering its effect on the individual’s decision at Time 1, which is given by Eq. (4). Let the social welfare function SW k be the same as the representative agent’s expected utility, that is,Footnote 34

The first derivative of the social welfare function is

The above equation shows that a change in policy t affects social welfare through two channels. The first channel is the classical effect of a change in policy t on the realised level of final wealth, w k ∗. It can be decomposed into an indirect effect caused by the implied change in the individual’s decision q k ∗(t) at Time 1 and a direct effect of a change in policy on wealth, that is,

The corresponding effects on social welfare are given by

and

By the envelope theorem, the indirect effect is zero, that is, Eq. (4) implies Δ k q(t)=0. The sign of the direct effect is ambiguous since a change in policy t might reallocate wealth across different states and thus increase final wealth in some states at the expense of a decrease in other states.

We note that if (∂w k ∗)/(∂t)=c⋅(∂w k ∗)/(∂q) for all x, where c is a constant, then the direct effect is zero, since

The condition (∂w k ∗)/(∂t)=c⋅(∂w k ∗)/(∂q) means that, at each state, (∂w k ∗)/(∂t)/(∂w k ∗)/(∂q) is equal to a constant. Thus, the impact of the government’s decision is a re-scale of that of the individual’s decision. Put differently, the individual can duplicate the influence of the government’s decision. We further discuss this condition in the following section on income tax deduction for uninsured losses.

The second channel through which a change in policy t affects social welfare is through its impact on the level of wealth under the foregone best alternative, w max. This channel exists only for regret-sensitive individuals, that is, for k>0. Again, the overall effect can be decomposed into an indirect effect caused by the implied change in the foregone best alternative q max(t, x) and a direct effect of a change in policy on wealth, that is,

The corresponding effects on social welfare are

and

Again, the envelope theorem implies that the indirect effect is zero, that is, Eq. (2) implies  The sign of the direct effect

The sign of the direct effect  depends on how a change in policy t affects the distribution of wealth levels under the foregone best alternatives. Suppose that an increase in t reduces the wealth levels the individual could have achieved under the foregone best alternatives in each state, that is, (∂w

max)/(∂t)<0 for all x. This reduces the feeling of regret towards those wealth levels and thereby increases social welfare.

depends on how a change in policy t affects the distribution of wealth levels under the foregone best alternatives. Suppose that an increase in t reduces the wealth levels the individual could have achieved under the foregone best alternatives in each state, that is, (∂w

max)/(∂t)<0 for all x. This reduces the feeling of regret towards those wealth levels and thereby increases social welfare.

The following proposition summarises the above discussions and provides a condition under which the anticipatory feeling of regret influences the optimal governmental policy t.

Proposition 1

-

Suppose that the social welfare function is identical to the representative agent’s expected utility and let t k ∗ denote the optimal governmental policy for k⩾0. The optimal policy t k ∗ for a regret-sensitive individual, k>0, differs from the optimal governmental policy t 0 ∗ for an individual who is not regret sensitive, if

Proof.

-

See Appendix A □

Suppose that the optimal policy t 0 ∗ for individuals who are not regret sensitive is for the government to not intervene into private decisions. If individuals are regret sensitive, then Condition (13) specifies a condition under which it is optimal for the government to intervene. This condition depends on how a change in governmental policy affects and reduces the anticipatory feeling of regret. This feeling depends on the difference between the utility levels of the forgone best alternative and the realised wealth distributions, g(u(w max)−u(w 0 ∗)), where the disutility of regret is convex in this difference. This implies that the regret-sensitive individual prefers having higher levels of realised wealth being matched with higher levels of wealth that the individual could have obtained from the foregone best alternative. Put differently, the individual favours differences between the realised levels of wealth and the maximum levels of wealth towards which the individual regrets being evenly distributed across different states of nature. That is, the individual prefers experiencing a similar degree of regret across all states of nature to experiencing little or no regret in some states while a strong degree of regret in other states.

In this context, Condition (13) shows that there are three channels through which a governmental policy can more evenly distribute the differences between the realised and the foregone best alternative levels of wealth across different states of nature and thereby reduce the feeling of regret.

First, governmental policy aiming at increasing the realised levels of wealth w* and/or reducing their spreads, while keeping the foregone best alternative levels of wealth w max unchanged, reduces regret. Such policy would also increase welfare of risk-averse individuals who are not sensitive to regret. Second, governmental policy aiming at reducing the wealth levels of the foregone best alternative w max and/or reducing their spread, while not affecting realised levels of wealth w*, also reduces regret. Last, governmental policy can reduce regret by reducing the spread of differences between realised and foregone best alternative levels of wealth.

From the above discussion, we obtain the following corollary.

Corollary 1

-

Suppose that the social welfare function is identical to the representative agent’s expected utility. If (∂w 0 ∗)/(∂t)=((∂w 0 ∗)/(∂q))((dq 0 ∗)/(dt)) for all x, then the optimal policy t k ∗ for a regret sensitive individual, k>0, is greater than the optimal policy t 0 ∗ for an individual who is not regret sensitive, if

The above corollary indicates that if governmental intervention reduces the maximum level of wealth the individual could have obtained in each state, then it reduces the pain associated with regret and thereby increases individual welfare.

In the section below, we examine tax deduction for uninsured losses as a specific governmental policy and focus on the trade-off between Δ

k

w(t) and  . We show that governmental intervention in this context can be justified based on reducing individuals’ feeling of regret.

. We show that governmental intervention in this context can be justified based on reducing individuals’ feeling of regret.

Income tax deduction for uninsured losses

The Department of Treasury of the United States allows individuals to deduct from their taxable income some of their uninsured losses, such as casualty losses due to natural catastrophes (e.g. after Hurricane Katrina), theft losses, or medical and dental expenses. KaplowFootnote 35 argues that this type of tax deduction for individuals’ net losses serves as partial insurance and distorts insurance decisions in the private insurance market. Since tax deductions only apply to the uninsured portion of losses, Kaplow35 shows that such tax deductions are welfare decreasing. It has been recently argued that a tax deduction system can improve welfare if the private insurance market is restricted to offer upper-limit policies,Footnote 36 or if insurance companies can become insolvent.Footnote 37 The aim of this section is to argue that tax deductions of net losses can improve welfare by reducing individual’s pain associated with the feeling of regret. We show that this reduction in regret can outweigh the negative effect of tax deduction through distorting individuals’ insurance decision.

We adopt the setup of Kaplow35 in which the individual is endowed with some initial wealth w

0 and with probability π faces a loss of size l<w

0, that is,  with associated probabilities 1−π and π, respectively. The sequence of events is as follows.

with associated probabilities 1−π and π, respectively. The sequence of events is as follows.

Time 0 The government sets a tax deduction rate t at which the individual is allowed to deduct the non-insured portion of the loss. The expected revenue loss is financed by a lump-sum tax τ.

Time 1 The individual chooses the amount of insurance coverage q∈[0, l] in a private insurance market at a premium P=(1+λ)πq, where λ⩾0 is the loading factor proportional to the expected insurance payment.

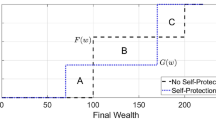

Time 2 At Time 2, after the state variable  has realised, the individual regrets that he did not choose the foregone best alternative

has realised, the individual regrets that he did not choose the foregone best alternative  which is state-wise given byFootnote 38

which is state-wise given byFootnote 38

The individual would have chosen full or no insurance coverage had he known that a loss realises or not, respectively. Note that both choices,  and

and  do not depend on the tax deduction rate t, that is,

do not depend on the tax deduction rate t, that is,  There is no effect of governmental intervention on the ex post optimal choice, that is, ∂q

max/∂t=0. However, there is a direct effect on the reference level of wealth, w

max, towards which the individual regrets since

There is no effect of governmental intervention on the ex post optimal choice, that is, ∂q

max/∂t=0. However, there is a direct effect on the reference level of wealth, w

max, towards which the individual regrets since

Time 1 At Time 1, taking t and τ as given, the insured will choose optimal private insurance to maximise his expected utility. The final levels of wealth in the two states are given by

with P=(1+λ)πq. The objective function is

In the following proposition we show that it is optimal for the individual to partially insure. This result holds for any loading factor λ⩾0 and tax rate t<1−(1+λ)π.Footnote 39

Proposition 2

-

Suppose individuals can deduct uninsured losses from their taxes at the rate t. Then it is optimal for a regret-sensitive individual to not purchase full insurance, that is, q k ∗(t)<l, for all k>0, loading λ⩾0 and tax rate t⩾0.

Proof.

-

See Appendix A. □

Consistent to the finding of Braun and Muermann,25 Proposition 2 shows that a regret-sensitive decision-maker purchases partial coverage even if insurance is actuarially fair. The case discussed by Braun and Muermann25 is a special case of our results, when the government does not allow any tax deduction for individual’s net losses.

In the following proposition, we show that the optimal amount of private insurance coverage is decreasing in the tax rate.

Proposition 3

-

Suppose individuals can deduct uninsured losses from their taxes at the rate t. Then the optimal level of insurance coverage for a regret-sensitive individual is decreasing in the tax rate, that is, dq k ∗(t)/dt<0, for all k>0, loading λ⩾0 and tax rate t⩾0.

Proof.

-

See Appendix A □

We thus confirm Kaplow’s35 result that a tax deduction system crowds out private insurance. This also holds true for regret-sensitive individuals.

Time 0 At Time 0, the government choose the optimal tax deduction rate t. For comparison, we assume a proportional loading factor λ for the lump-sum tax that is identical to the one in the private insurance market.Footnote 40 The self-financing lump-sum tax is thus given by

The government solves the following programme

where

In the general model above, we have shown that differentiating this expression with respect to t yields two effects on social welfare. The first effect, Δ

w

, is caused by the direct effect of a change in the tax rate t on the realised wealth distribution. The second effect,  , is due to the direct effect of a change in the tax rate t on the wealth distribution under the foregone best alternatives. In the following proposition, we show that the effect on realised wealth is only of second order while the effect on wealth under the foregone best alternative is of first order.

, is due to the direct effect of a change in the tax rate t on the wealth distribution under the foregone best alternatives. In the following proposition, we show that the effect on realised wealth is only of second order while the effect on wealth under the foregone best alternative is of first order.

Proposition 4

-

Suppose individuals can deduct uninsured losses from their taxes at the rate t. Then the optimal tax deduction rate for an individual who is not regret sensitive is zero, whereas the optimal tax deduction rate for a regret-sensitive individual is strictly positive, that is, t 0 ∗=0 and t k ∗>0 for k>0.

Proof.

-

See Appendix A. □

In this example, the conditions in Corollary 1 are satisfied. Allowing individuals to deduct their uninsured losses from their taxes decreases foregone best alternative levels of wealth w max and thereby reduces regret. Thus, the social welfare increases.

Extensions

In this section, we extend our setting by considering (1) an alternative social welfare function and (2) heterogenous individuals.

Alternative social welfare function

The government could have a different weight on the regret function and set the social welfare function as

where θ is a constant. If θ=k, then the social welfare function is identical to the agents’ expected utility and the results of the sections ‘Preferences and general setup’ and ‘Income tax deduction for uninsured losses’ hold. If θ≠k, then the government puts a different weight on the regret function than the representative individual. In the special case θ=0, the government’s objective is to maximise the individual’s welfare without considering regret. The government might consider the feeling of regret as a bias distorting individuals’ decisions and should therefore be excluded in a positive welfare analysis. Many psychologists argue that individuals overvalue anticipated regret at the time individuals are making decisions. Ex post, we suffer from regret, but only for a short period of time and thus the feeling of regret has only a negligible impact on our overall well-being. Therefore, the social welfare function should potentially exclude the regret function. The government would then act as a paternalist by correcting the decisions of individuals who take anticipated regret into account in their decision process.Footnote 41

Since the decisions at Time 2 and Time 1 are made by the individual, the conditions and results of the general model in the section ‘Preferences and general setup’ and the tax deduction example in the section ‘Income tax deduction for uninsured losses’ are equally valid in this setting. As in the previous sections, let q

k

∗=q

k

∗(t) denote the inner solution to Eq. (4) and  the final wealth under the decision q

k

∗. At Time 0, however, the objective function of the government is different and the first-order condition of the government’s problem in this case is

the final wealth under the decision q

k

∗. At Time 0, however, the objective function of the government is different and the first-order condition of the government’s problem in this case is

Decomposing these effects into the direct and indirect effects, we obtain

Since the individual’s first-order condition is identical to Eq. (4), the indirect effect caused by the implied change in the individual’s decision q k ∗(t) at Time 1 does not disappear for θ≠k, that is,

The direct effect of a change in policy on wealth is now given by

The third and fourth terms of Eq. (17) reflect the impact of governmental policy on the level of wealth under the foregone best alternative, w max. As in the general model, there is a direct and indirect effect given by

and

Since the indirect effect through affecting the individual’s foregone best alternative decision, q

max, is proportional to the weighting factor on regret, θ or k, respectively, the envelope theorem applies and the indirect effect is zero, that is,  . In summary, whether the government should intervene into the private market to correct individuals’ choices depends on the net effect of

. In summary, whether the government should intervene into the private market to correct individuals’ choices depends on the net effect of

Suppose the government believes that anticipating regret distorts individuals’ decisions and thus, paternalistically, sets the optimal policy to maximise social welfare without regret while knowing that individuals’ decisions are biased by anticipated regret. In this case θ=0 and we have

and

Let us discuss the effect of such governmental intervention in the context of the tax deduction example of the section ‘Income tax deduction for uninsured losses’. Suppose that the insurance loading is zero, that is, λ=0. The social optimum for θ=0 is full insurance coverage. For an individual who is not regret sensitive, the optimal governmental policy is t 0 ∗=0 and the individual purchases full coverage in the private insurance market, q 0 ∗(0)=l. For a regret-sensitive individual, we have

Since u′(w l, k ∗)>u′(w nl, k ∗) and (dq k ∗(t))/(dt)<0 (see Proposition 3), we derive

Governmental intervention in form of providing implicit insurance through tax deduction crowds out private insurance and thereby reduces social welfare. On the other hand, we have

since q k ∗(0)<l and u′(w l,k ∗)>u′(w nl,k ∗).

The intuition for the positive effect of governmental intervention on wealth Δ0 w(0)>0 is that regret-sensitive individuals optimally purchase partial coverage if the insurance premium is fair.25 Since a tax deduction system for net losses serves as a public insurance as shown by Kaplow,35 social welfare from the government’s point of view increases, since the government provides additional implicit insurance coverage.

The sign of the overall effect

is ambiguous.

Heterogenous individuals

We now consider heterogenous individuals. Suppose that there is heterogeneity in the extent to which individuals are prone to take regret into account when they make decisions.Footnote 42 To simplify the model, let us assume that there are two types of individuals: a proportion ϕ of regret-sensitive individuals with some k>0 and a proportion 1−ϕ of individuals who are not regret sensitive, that is, with k=0.

At Time 1, individuals’ optimal choice q k ∗ is still determined by Eq. (4) for both types, k>0 and k=0.

At Time 0, we assume that the social welfare function is the weighted average of the two types’ welfare

Applying the envelope theorem yields that a change in governmental policy causes a change in social welfare according to

If the optimal policy for the two types differs (see Condition (13) in Proposition 1), then the overall effect of governmental intervention is ambiguous and depends on the relative proportion ϕ of the two types.

Let us discuss the overall effect of governmental intervention in the context of the tax deduction example of the section ‘Income tax deduction for uninsured losses’. Again, we consider the case of no insurance loading, that is, λ=0. We know that q 0 ∗(0)=l and q k ∗(0)<l. The lump-sum tax is given by

For individuals who are not regret sensitive, introducing a tax deduction system has the following effect:

For the last equality, we note that (dτ(0))/(dt)=πϕ(l−q k ∗(0))>0 and that the first-order condition (19) at Time 1 for k=0 implies u′(w l, 0 ∗)=u′(w nl, 0 ∗). Individuals who are not regret sensitive subsidise regret-sensitive individuals who partially insure through the lump-sum tax. This subsidy reduces welfare for individuals who are not regret sensitive.

For regret-sensitive individuals, introducing a tax deduction system has the following wealth effect:

Again, we applied the first-order condition (19) at Time 1 for k>0. Regret-sensitive individuals benefit in two ways from the subsidy provided by individuals who are not regret sensitive through the lump-sum tax. First, there is a pure wealth effect since the subsidy increases their wealth levels in each state. But second, this wealth increase also reduces the difference to the wealth levels of the foregone best alternative and thereby reduces the disutility from regret. Overall, despite the discretionary effect, the lump-sum tax might in sum increase social welfare due to the additional reduction of regret.

Moreover and as discussed in the section ‘Income tax deduction for uninsured losses’, regret-sensitive individuals benefit from the governmental provision of insurance since it reduces the wealth levels of the foregone best alternative towards which these individuals regret. The effect is given by

The overall effect on social welfare is then

for all 0<ϕ⩽1. The last inequality follows since regret-sensitive individuals are partially insured and their wealth in the state of a loss is thus below the wealth of the fully insured individuals who are not sensitive to regret. Therefore, u′(w l, k ∗)>u′(w l, 0 ∗). This implies that it is socially optimal to introduce a tax deduction system for uninsured losses as long as some individuals in the population are regret sensitive. The reason is that the subsidy for regret-sensitive individuals is not only a pure wealth transfer but has the additional positive effect for regret-sensitive individuals of reducing their feeling of regret.

Conclusion

Governmental intervention in markets shifts individual choices in private markets. We emphasise that such a shift can be beneficial if individuals regret about foregone alternative choices. By directing choice the government not only distorts individual decisions in the private market but also reduces the feeling of regretting those decisions. We derive a general model to explore this trade-off. In the example of tax deduction for non-insured losses, we show that governmental intervention is beneficial. Last, we analyse different social welfare functions and heterogeneous individuals. Governmental intervention can still be justified in these extended settings.

Notes

Glaeser (2006) defines soft paternalism as “governmental policies that change behavior without actually changing the choice sets of consumers”.

We note that directing individuals’ choice does not alleviate the feeling of disappointment. Regret arises from comparing the actual decision outcome with counterfactual outcomes in the same state of the world, but derived from foregone alternative decisions. Disappointment, instead, arises from comparing the actual outcome with counterfactual outcomes in different states of the world (Loomes, 1988; Zeelenberg et al., 2000b). Since directing individuals’ choice does not change the state space, such governmental interventions do not effect the feeling of disappointment.

Kuhn et al. (2011) examine the social effects of the Duch postcode lottery and find that the nonparticipants who live next door to winners significantly consume more on car than other nonparticipants.

Sarver (2008) provides an axiomatic representation of preferences over menus of lotteries that account for the individual’s preference to reduce the number of choices due to anticipated regret.

Germany and Japan, for example, mandate a principal guarantee such that all contributions are guaranteed in nominal terms. In Chile and Mexico a minimum pension payment of about 25 and 40 per cent, respectively, of average wages is guaranteed.

We thus assume that the individual does not associate a cost to blaming the government in case the imposed policy t turns out to be suboptimal ex post. This assumption is supported by empirical evidence showing that responsibility for choices is positively related to the subsequent feeling of regret (Zeelenberg et al., 1998; Ordóñez and Connolly, 2000; Zeelenberg et al., 2000a; Botti and McGill, 2006).

The second derivative is given by

If final wealth w is linear or convex in q, then the second-order condition holds. Moreover, if the individual is not regret sensitive, that is, k=0, then the second-order condition also holds. In general, we assume that (d2 E[v(w, w max)])/(dq 2)<0.

We discuss alternative social welfare functions in the section “Extensions”.

Note that the individual has paid the lump-sum tax τ at Time 0 before he made his choice q at Time 1.

For t⩾1−(1+λ)π, it is state-wise optimal to set q k ∗=0. Since our focus is on the interplay between the private insurance market and tax deductions, we assume t<1−(1+λ)π.

If the government were more or less efficient in financing the expenditure than the private insurance market, this would add an additional advantage or disadvantage in providing insurance coverage through the government.

We deeply appreciate an anonymous referee pointing out the possiblity of this case.

We deeply appreciate an anonymous referee for the suggestion of heterogeneity.

This condition implies that Equation (10) is satisfied, that is, (∂w k *)/(∂t)| t=0=c(∂w k ∗)/(∂q)| t=0 for all x for some constant c.

References

Bell, D.E. (1982) ‘Regret in decision making under uncertainty’, Operations Research 30 (5): 961–981.

Beshears, J., Choi, J.J., Laibson, D. and Madrian, B.C. (2008) ‘How are preferences revealed?’, Journal of Public Economics 92 (8–9): 1787–1794.

Bleichrodt, H., Cillo, A. and Diecidue, E. (2010) ‘A quantitative measurement of regret theory’, Management Science 56 (1): 161–175.

Botti, S. and McGill, A.L. (2006) ‘When choosing is not deciding: The effect of perceived responsibility on satisfaction’, Journal of Consumer Research 33 (2): 211–219.

Braun, M. and Muermann, A. (2004) ‘The impact of regret on the demand for insurance’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 71 (4): 737–767.

Camerer, C.F., Issacharoff, S., Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T. and Rabin, M. (2003) ‘Regulation for conservatives: Behavioral economics and the case for “asymmetric paternalism”’, University of Pennsylvania Law Review 151 (3): 1211–1254.

Camille, N., Coricelli, G., Sallet, J., Pradat-Diehl, P., Duhamel, J.-R. and Sirigu, A. (2004) ‘The involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex in the experience of regret’, Science 304 (5674): 1167–1170.

Choi, J.J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B.C. and Metrick, A. (2006) ‘Saving for retirement on the path of least resistance’, in E. McCaffrey and J. Slemrod (eds), Behavioral Public Finance: Toward a New Agenda, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 304–351.

Coricelli, G., Critchley, H.D., Joffily, M., O’Doherty, J.P., Sirigu, A. and Dolan, R.J. (2005) ‘Regret and its avoidance: A neuroimaging study of choice behavior’, Nature Neuroscience 8 (9): 1255–1262.

Filiz-Ozbay, E. and Ozbay, E.Y. (2007) ‘Auctions with anticipated regret: Theory and experiment’, American Economic Review 97 (4): 1407–1418.

Glaeser, E.L. (2006) ‘Paternalism and psychology’, University of Chicago Law Review 73 (1): 133–156.

Gollier, C. and Salanié, B. (2006) Individual decisions under risk, risk sharing, and asset prices with regret, working paper.

Gruber, J. and Köszegi, B. (2004) ‘Tax incidence when individuals are time-inconsistent: The case of cigarette excise taxes’, Journal of Public Economics 88 (9–10): 1959–1987.

Huang, R.J. and Tzeng, L.Y. (2007a) ‘Optimal tax deductions for net losses under private insurance with an upper limit’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance 74 (4): 883–893.

Huang, R.J. and Tzeng, L.Y. (2007b) ‘Insurer’s insolvency risk and tax deductions for the individual’s net losses’, Geneva Risk and Insurance Review 32 (2): 129–145.

Iyengar, S.S. and Lepper, M.R. (2000) ‘When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (6): 995–1006.

Kaplow, L. (1992) ‘Income tax deductions for losses as insurance’, American Economic Review 82 (4): 1013–1017.

Kuhn, P., Kooreman, P., Soetevent, A. and Kapteyn, A. (2011) ‘The effects of lottery prizes on winners and their neighbors: Evidence from the Dutch postcode lottery’, American Economic Review 101 (5): 2226–2247.

Laciana, C.E. and Weber, E.U. (2008) ‘Correcting expected utility for comparisons between alternative outcomes: A unified parameterization of regret and disappointment’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 36 (1): 1–17.

Larrick, R.P. and Boles, T.L. (1995) ‘Avoiding regret in decisions with feedback: A negotiation example’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 63 (1): 87–97.

Loomes, G. (1988) ‘Further evidence of the impact of regret and disappointment in choice under uncertainty’, Economica 55 (217): 47–62.

Loomes, G., Starmer, C. and Sugden, R. (1992) ‘Are preferences monotonic—testing some predictions of regret theory’, Economica 59 (233): 17–33.

Loomes, G. and Sugden, R. (1982) ‘Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty’, Economic Journal 92 (368): 805–824.

Madrian, B.C. and Shea, D.F. (2001) ‘The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) participation and savings behavior’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 116 (4): 1149–1187.

Muermann, A., Mitchell, O.S. and Volkman, J. (2006) ‘Regret, portfolio choice, and guarantees in defined contribution schemes’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics 39 (2): 219–229.

Muermann, A. and Volkman, J. (2006) Regret, pride, and the disposition effect, Working Paper 06–08 in PARC working paper series.

O’Donoghue, T. and Rabin, M. (2003) ‘Studying optimal paternalism, illustrated by a model of sin taxes’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 93 (2): 186–191.

O’Donoghue, T. and Rabin, M. (2006) ‘Optimal sin taxes’, Journal of Public Economics 90 (10–11): 1825–1849.

Ordóñez, L.D. and Connolly, T. (2000) ‘Regret and responsibility: A reply to Zeelenberg et al. (1998)’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 81 (1): 132–142.

Quiggin, J. (1994) ‘Regret theory with general choice sets’, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 8 (2): 153–165.

Ritov, I. (1996) ‘Probability of regret: Anticipation of uncertainty resolution in choice’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 66 (2): 228–236.

Sandroni, A. and Squintani, F. (2007) ‘Overconfidence, insurance, and paternalism’, American Economic Review 97 (5): 1994–2004.

Sarver, T. (2008) ‘Anticipating regret: Why fewer options may be better’, Econometrica 76 (2): 263–305.

Simonson, I. (1992) ‘The influence of anticipating regret and responsibility on purchase decisions’, Journal of Consumer Research 19 (1): 105–118.

Sugden, R. (1993) ‘An axiomatic foundation of regret’, Journal of Economic Theory 60 (1): 159–180.

Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2003) ‘Libertarian paternalism’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 93 (2): 175–179.

Zeelenberg, M. (1999) ‘Anticipated regret, expected feedback and behavioral decision making’, Journal of Behavioral Decision-Making 12 (2): 93–106.

Zeelenberg, M. and Pieters, R. (2004) ‘Consequences of regret aversion in real life: The case of the Dutch postcode lottery’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 93 (2): 155–168.

Zeelenberg, M. and Pieters, P. (2007) ‘A theory of regret regulation 1.0’, Journal of Consumer Psychology 17 (1): 3–18.

Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W.W. and Manstead, A.S.R. (1998) ‘Reconsidering the relation between regret and responsibility’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 74 (3): 244–272.

Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W.W. and Manstead, A.S.R. (2000a) ‘Regret and responsibility resolved? Evaluating Ordóñez and Connolly’s (2000) conclusions’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 81 (1): 143–154.

Zeelenberg, M., van Djik, W.W., Manstead, A.S.R. and van der Pligt, J. (2000b) ‘On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: The psychology of regret and disappointment’, Cognition and Emotion 14 (4): 521–541.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Christian Laux, Gyöngyi Lóránth, and seminar participants of the EGRIE meeting for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix A

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1

Proof.

-

The first-order condition for k=0 is given by (dSW 0(t))/(dt)=E[(∂w 0 ∗)/(∂t)u′(w 0 ∗)]=0 which defines t 0 ∗. Evaluating the first derivative of social welfare for k>0 at t=t 0 ∗ yields

Condition (13) implies that social welfare for k>0 can be improved by setting t k ∗≠t 0 ∗. □

Proof of Corollary 1

The condition  for all x and some constant c implies Δ

k

w(t

0

∗)=0 (see Eq. (10)). Therefore,

for all x and some constant c implies Δ

k

w(t

0

∗)=0 (see Eq. (10)). Therefore,

If  for all x, then (dSW

k

(t

0

∗))/(dt)>0 and thus t

k

∗>t

0

∗ for all k>0. □

for all x, then (dSW

k

(t

0

∗))/(dt)>0 and thus t

k

∗>t

0

∗ for all k>0. □

Proof of Proposition 2

Proof.

-

The first derivative of (16) is given by

Note that if t⩾1−(1+λ)π then (dE[v(w, w max)])/(dq)<0 for all q and q k ∗(t)=0. Evaluating the first derivative at q=l yields

for all λ⩾0 and t⩾0. The first inequality holds since g′(u(w nl max)−u(w 0−(1+λ)πl−τ))>g′(0). (dE[v(w, w max)])/(dq)| q=l <0 implies that q k ∗(t)<l. □

Proof of Proposition 3

Proof.

-

Totally differentiating the first-order condition (dE[v(w, w max)])/(dq)=0 with respect to t yields

The second-order condition is satisfied in this setting (d2 E[v(w, w max)])/(dq 2)<0, since u is concave, g is convex, and w is linear on q. Thus,

For the cross-partial derivative we derive

Therefore, (dq k ∗(t))/(dt)<0. □

Proof of Proposition 4

Proof.

-

The first effect on social welfare is given by

Note that (dτ(0))/(dt)=(1+λ)π(l−q k ∗(0)) which yields

Evaluating the first-order condition at Time 1, Eq. (A.1), at t=0 yields

Therefore, Δ k w(0)=0 for all k⩾0. For an individual who is not regret sensitive, k=0, Δ k w is the only effect on social welfare and the optimal tax deduction rate is thus zero, t 0 ∗=0.Related to the discussion in the previous section, in this example the following condition holds.

in both states of nature.Footnote 43 Note that this condition holds since the government’s tax deduction loading is identical to the insurance loading in the private market. If the government is less efficient than the private market, which means that the government has a higher loading than the private insurance, then we will have Δ k w(0)<0. The second effect on social welfare applies only to regret-sensitive individuals, that is, for k>0. It is given by

Note that (dτ(t))/(dt)|

t=0=(1+λ)π(l−q

k

∗(0))>0 since q

k

∗(0)<l (see Proposition 2). Therefore,  . Eq. (6) evaluated at t=0 then implies

. Eq. (6) evaluated at t=0 then implies

and thus, t k ∗>0 for all k>0. □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, R., Muermann, A. & Tzeng, L. Regret and Regulation. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 39, 65–89 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/grir.2013.4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/grir.2013.4