Abstract

Although annual statistics present data on the growth of endowments for specific institutions (CAE, 2006; NACUBO, 2006), relatively little research has been conducted to better understand the institutional factors that account for differential changes in the overall endowment value of institutions. This study is to determine what relationships exist between institutional characteristics and endowment growth by comparing and categorizing institutions with endowment market values in excess of $120 million in 1995 and tracing the pattern of growth for the past decade. The set of 147 institutions included 100 private institutions and 47 public institutions of several types (that is, 94 research/doctoral universities, 8 master's universities and 45 liberal arts colleges based on the Carnegie classification). Based on the literature and discussion about endowment growth, the following 10 variables were identified as possible predictors of growth in endowments: governance, institution type, enrollment, geographical location, region, research activities, state funding, tuition revenue, alumni giving rate (AGR) and student selectivity. The findings revealed that endowment growth was closely intertwined with a variety of crucial institutional characteristic factors, including SAT scores, R&D expenditures, AGR and tuition revenue, which indicates that these institutional characteristics are significantly and positively correlated to endowment growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Higher education in the United States has certain features that leap out when compared to other advanced industrial societies. There is an enormous diversity among institutions in their size, functions, curricula, sources of support and so on (Trow, 1988). The diversity in the source of voluntary support (derived from alumni, foundations, corporations, religious groups and other sources) enables the United States' higher education system to grow at a phenomenal rate, and has allowed colleges and universities to develop their own unique characteristics through these different channels of contributions.

These contributions enabled higher education institutions to develop endowments, where income from endowments could be used to support program activities, thus improving overall financial stability (Bogue and Aper, 2000; Thelin, 2004). As a result, some universities with large endowments have become very wealthy institutions. For instance, by fiscal year 2005, the market value of endowment assets of Harvard University was US$25 billion, whereas Yale University's $15 billion ranked second (National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), 2006). As a public university, the University of Texas has $11 billion in endowment assets and is ranked fourth on the list. Of the top 20 institutions with the largest endowment assets, 15 are private institutions and 5 are public (NACUBO, 2006). Figure 1 illustrates the top 20 endowment values in 2005.

Top 20 endowments in 2005. Dollar amounts are in billions.Source: The data are taken from 2005 NACUBO Endowment Study by NACUBO (2006). Washington DC: Author.

For American institutions, the NACUBO Endowment Study shows that endowment market values in recent decades have increased substantially. As The Chronicle of Higher Education indicates, the combined market value of all endowments in the year 2006 exceeded the gross domestic product of Hong Kong and Thailand combined (Di Mento, 2006). The current levels of endowment assets far exceed what was expected a decade ago. It raises questions regarding the evolution of endowments. Why do some prosper, whereas others do not? How have the value and size of endowments changed for colleges and universities in the past decades? Thus, it is beneficial to analyze institutional patterns in measuring the growth of endowment market values, to gain a better understanding of those similarities and disparities among different institutions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

As history noted, private philanthropy was the oldest source of support for higher education, particularly private institutions (Patterson, 1976). Endowments have been part of the financial support of colleges and universities for more than 300 years (American Council on Education (ACE), 2000). Harvard and Yale, for example, had endowments in 2005 valued at $25 billion and $15 billion, respectively. Although these two institutions are the best endowed in the nation, there are hundreds of others that also have substantial endowments (Hansmann, 1990). With such sizeable endowment assets, institutions start to face a series of questions. What is the real objective, role or function of the endowment? How large should an endowment be? How is the endowment related to the institution's academic mission?

Several researches have identified profound effects on the endowment in higher education development. Massy (1990) pointed out one important concept regarding endowment income, stating that the endowment grants independence to the institution from economic and political forces, thus representing more than just another source of funds. Morrell (2000) argued that institutions with larger endowments would not necessarily minimize charges for tuition fees. Morrell (2000) indicated that high-quality education is expensive, and to maintain a position at the top of the quality ladder requires both a large endowment and high student fees to exist at the same time in practice.

Swensen (2000) articulated that the endowment size was strongly correlated to institutional quality, which was based on a survey of major private institutions, categorized as research universities. This survey shows that larger, better-endowed organizations score higher in the US News and World Report rankings of educational institutions. Cunningham and Cochi-Ficano (2002) presented the sources of financial sensitivity that were linked to a variety of institutional features. Institutional characteristics (or traits) included academic reputation, usually measured by SAT scores, as well as its faculty–student ratio, its function and structure, and the vocational choices of its graduates. All the above affected the flow of contributions to an institution.

Geiger (1985) analyzed the logic behind the American higher education system before 1910. The results showed that some institutions showed distinct changes in growth thereafter, based on differences in the nature of voluntary support. The rapid growth of voluntary support contributions to endowments symbolized a transformation for wealthy institutions. Leslie and Ramey (1988) opined that institutional size was an important and probable trait to all donor groups, because public visibility has a vital correlation with enrollment size. In addition, donors also responded well to those institutions of high prestige and prominence, based on the age and quality rating of the institution.

Cunningham and Cochi-Ficano (2002) presented the sources of financial sensitivity that were linked to a variety of institutional features. Institutional characteristics (or traits) included academic reputation, usually measured by SAT scores, as well as its faculty–student ratio, its function and structure, and the vocational choices of its graduates. All the above affected the flow of contributions to an institution.

Oster (2003) attempted to review the effect of endowment growth on college and university donor behavior. This study employed past endowment growth and several institutional variables to examine whether such growth had any impact on the source of giving from alumni and non-alumni groups. The results suggested that traditional donors seemed to reduce their gifts and donations to colleges and universities based on the perceived wealth of the institution.

METHOD

This study was undertaken to explore whether any correlations existed between a higher education institution's characteristics and the growth of its endowments, and if those characteristics could be used to predict future endowment growth. In addition, this study analyzes the relationships between endowment growth and various institutional characteristics, as well as some of the institution-specific variables, including measures of both type and quality of institution.

The units of analysis in this study are educational institutions, selected from the 1995 and 2005 Voluntary Support of Education (VSE) Report (CAE, 1996, 2006). Institutions were selected that had an endowment asset market value of more than $120 million in 1995 and that had reported to the VSE Survey for the period beginning on 1 July 1995 and ending on 30 June 2005. A total of 147 institutions were selected based on having endowment asset market values of more than $120 million in 1995. This group consists of 47 private and 47 public research universities, 8 private master's universities and 45 private liberal arts universities. (See Appendix A for a complete list of these institutions.)

Several institution-level sources of data are employed in this study. The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), developed and maintained by the United States Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), is a system of surveys designed to collect data from all postsecondary educational institutions and educational organizations in the United States. Another source of information is from the VSE report. The Council for Aid to Education (CAE) annually publishes a report of VSE, which is derived from a survey of annual contributions to colleges, universities and schools, and contains a listing of private endowments to higher education on a national basis (CAE, 2006).

The third source of data is from the National Science Foundation's (NSF's) Survey of Research and Development Expenditures at Universities and Colleges. The Integrated Science and Engineering Resources Data System (WebCASPAR) is a database system containing the results of the Academic R&D Expenditures Survey. The last source of information is US News & World Report's (USNWR) annual ‘America's Best Colleges’ ranking of colleges and universities. (See Appendix B for a complete list of these database systems.)

Multiple regression analysis was used to elaborate the relationship between various institutional factors and endowment variables. Several dependent variables are utilized in the regression models for the study, such as the total value for all 11 years, individual yearly endowment value and period endowment change. Different types of institution endowments and endowment value per student are also used as dependent variables as a basis for comparison in different regression models. Based on the literature and discussion about endowment growth, the following 10 variables were identified as possible predictors of growth in endowments: governance, institution type, enrollment, geographical location, region, research activities, state funding, tuition revenue, alumni giving rate (AGR) and student selectivity.

The regression model for the first research question is as follows:

where Endowment performance is (1) endowment value by year and (2) endowment per student by year; Gov is public or private institution; Type is type of institutions based on the Carnegie classification; Enrol is headcount of students at the beginning of the period; Loc is the institution's location; R&D is academic research and development expenditures at the beginning of the period; Appr is dollar amount of state appropriations at the beginning of the period; SAT is student SAT/ACT scores at the beginning of the period; AGR is alumni giving rate at the beginning of the period; Tuition is tuition revenue at the beginning of the period; and Region is geographic region of institutions.

RESULT

Endowment change by institution type

The types of institutions were based on the 1994 Carnegie classification of institutions. Figure 2 compares changes in endowment values by institutional type during the period from 1995 to 2005. Figure 2 shows that research/doctoral institutions have the largest average endowment among the three types of institutions. The average endowment value of research universities is far greater than that of the other two types of institutions. Master's and liberal arts institutes are similar to each other in both average values and growth, with the latter slightly outperforming the former in both areas.

Table 1 presents the amount and the percentage change in endowment value for each type of institution. Research universities are the leaders among the three types of institutions in both the amount and percentage change in endowment value. The increase in endowment values for research universities ($1352 million) is about four times larger than that for master's ($287 million) and baccalaureate institutions ($306 million). In terms of percentage change, research institutions, with a 188 per cent increase from 1995 to 2005, also lead the other two groups by a large margin. The other two types of institutions lag far behind in both dollar amount and percentage of growth, with an increase of only 124 per cent for master's institutions and 118 per cent for liberal arts institutions.

ANALYSIS

Even when the comparison takes the size of enrollment into consideration by dividing the total endowment by the headcount of student enrollment, research institutions still take the lead in the growth trend. As endowment dollars per headcount enrollment amounts shown in Figure 3 and Appendix C reveal, liberal arts institutions have the highest amount of endowment per student among all types of institution in all years. Master's universities had the lowest endowment per headcount enrollment throughout the entire time frame. Again, research institutions enjoy the largest growth of 120 per cent, higher than the other two types of institutions (105 per cent for master's and 98 per cent for liberal arts institutions).

Regression result

The regression analysis in this study used the overall 11-year endowment market value as the dependent variable. The independent variables are those institutional characteristics listed in Table 2. These include student enrollment (enrollment), public or private institution (governance), state appropriations for each institution (appropriations), total tuition revenue for each institution (tuition), research and development (R&D) expenditures, entering students’ SAT scores (SAT), AGR, research university, master's university, institution located in an urban area, institution located in a suburban area, and institution located in the Northeast, Midwest, South and West.

As shown in Table 2, all dependent variables and those with the continuous value of independent variables, such as enrollment, state appropriation, tuition, R&D expenditures and SAT scores, were transformed into their natural log values. Year fixed effects have been included in the model to adjust for inflation, and also to better show the difference among the data and to see whether the model is sensitive to the yearly changes. The dependent variables in Table 2 are all institutions’ endowment, endowment per headcount enrollment and endowment of research institutions and liberal art institutions.

From the results of the regression model in Table 2, several significant variables for predicting the outcome of the endowment regressions are evident, such as tuition revenue, R&D expenditures, SAT scores and AGR. SAT scores appeared to be a significant factor for all four models in Table 2. One interpretation could be correlated to institutional prestige. The best endowed institutions are usually those highly esteemed or highly selective institutions with higher SAT scores, such as Harvard, Yale or Stanford. Higher SAT scores are normally associated with an institution's level of selectivity that contributes to raising its academic prestige. Regression results, which showed SAT scores as being significant variables in four regressions in Table 2, seemed to demonstrate this phenomenon and indicated that those institutions having higher SAT scores were poised for more rapid enhancement of endowment income.

Table 2 illustrates that tuition revenues posted mixed results. It shows a negative correlation for three regression models, but a positive correlation in only the research institution endowment regression. These results suggest that lower tuition revenue was still a significant factor for predicting endowment increases in the per headcount enrollment endowment and for liberal arts endowment models. In contrast, being an institution with large tuition revenue was a positive and significant predictor variable for the research institution group. The result that higher tuition revenue is a positive and significant factor for a research institution's endowment is likely owing to the fact that about half of the research institutions sampled were public institutions. Decreases in state appropriations and increasing budget constraints are forcing institutions to seek alternative financial resources to raise operating capital, such as by charging higher tuition fees and pursuing a variety of steps aimed at increasing voluntary support.

In today's increasingly competitive higher education environment, not only is there a need to raise tuition fees, but public institutions must also participate in fund-raising activities and do everything possible to increase endowment assets. Increasing tuition fees are sometimes only a triggered effect for public institutions that look to enhance endowment revenues when encountering financial constraints caused by state funding shortfalls. For the other half of the private research institutions, most are high selectivity and in a better position to raise tuition fees based on student demands and market competition. Overall, results for research institutions seem to offer a predictive value for tuition revenue and a corresponding increase of endowment revenue.

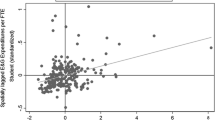

R&D expenditures appear to be a statistically significant variable for endowment and per headcount endowment models, as well as for research and liberal arts institution endowments, as shown in Table 2. R&D expenditures have served as an indicator for predicting endowment value, because institutions with more research activities would also be more likely to engage in more aggressive endowment-enhancing activities, with the aim of raising money for the support and welfare of staff and faculty, facility maintenance and establishment of new research (Geiger, 1985).

AGR is another significant institutional variable. AGR was an important variable that could be used to predict endowment performance and based on the fact that such factors are indicated as being positive and significant for many equations in this study. The percentage of alumni who gave donations to their schools was often used as an indicator of alumni satisfaction, as the USNWR suggested, and also served as part of the criteria in the ranking of America's Best College from USNWR (USNWR, 2006). One explanation is inferred from the Leslie and Ramey's study (1998), in which they pointed out that ‘the motivations for alumni to make contributions could be based on the desire to repay the institution for educational purposes or because of a heightened recognition of academic benefits provided by the institution’ (p. 121). This could suggest that those alumni who graduated from high-academic and well-esteemed institutions, which usually had higher SAT scores and R&D expenditures, seemed to be in a better position economically to repay the academic benefit.

In determining whether there existed any regional impact on endowment value or variety in the source of support, all selected institutions were grouped into four different regions, based on US Census Bureau classifications. Table 2 indicates that the West was the significant regional factor for predicting endowment per headcount enrollment, and also for the research institutional endowment, but was not significant for liberal arts institutional endowments. Furthermore, the size of the institution, which was measured by student enrollment, was also a significant characteristic for endowment, suggesting that large institutions are in a better position to generate higher endowment dollar values.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

The main idea of this research is aimed at analyzing institutional patterns and determining whether those similarities and disparities existing among different institutions provided a plausible explanation for endowment growth. In the first stage of descriptive analysis, different institutional classifications were found to reflect changes in endowment value allotments, giving rise to a variety of endowment distributions.

The all-years’ regression results indicate that the institutional characteristics relied significantly on the factor of SAT scores. Often associated with an institution's selectivity and prestige, SAT scores are shown as being a positive and influential factor for the all years’ regression. R&D expenditures appear to be a statistically significant variable for endowment and per headcount endowment models, as well as for research and liberal arts institution endowments, as shown in Table 2. R&D expenditures serve as an indicator for predicting endowment value, because more research activities usually require increased endowment fundraising in order to raise money needed to support those activities (Geiger, 1985).

Another factor also shown as being significant is that of tuition revenue, which came from the result based on four overall year endowment regressions. Tuition revenue appears to be a negatively significant factor in the all-years’ endowment, per headcount endowment, and liberal arts endowment models. However, tuition is shown as being both positive and significant for research institutions endowments.

In this study, AGRs are shown to be of great significance in endowment growth. Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate how AGRs are a direct indication of alumni satisfaction (Leslie and Ramey, 1988; Loessin et al, 1988; Brittingham and Pezzullo, 1990; Taylor and Martin, 1995; Ehrenberg (2001); Oster, 2003). Alumni donations have always been the main source of voluntary support, and represent the largest share of educational contributions. Therefore, institutions must focus on strategies that will make contributing more appealing to donors, while at the same time, fostering stronger relationships and ties with alumni, because these relationships are significantly rewarding in the long run.

Overall, the significant factors found in this study (R&D expenditures, SAT scores, student enrollment, research institutions and endowment growth) are closely intertwined with institutional quality and the size of the institutions. The findings further suggest that institutions with higher selectivity of students and high AGR with higher student enrollment and conducting more R&D activities contributed more toward endowment growth value.

This study was limited to those institutional characteristics considered to be important in the literature review. There are other institutional characteristics, which might also be important to endowment growth. As some institutional characteristics have not yet been explored in other literature, the results from this study can be used in further studies as a source of comparison. In future studies, researchers may attempt to combine institutional characteristics with managerial functions to provide more explicit explanations for endowment growth.

References

American Council on Education. (2000) Understanding College & University Endowment. Washington DC: ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 450 620.

Bogue, E.G. and Aper, J. (2000) Exploring the Heritage of American Higher Education: The Evolution of Philosophy and Policy. Phoenix: The Oryx Press.

Brittingham, B.E. and Pezzullo, T.R. (1990) The Campus Green: Fund Raising in Higher Education. Washington DC: School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University, pp. 3–91. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 1.

Council for Aid to Education. (1996) 1995 Voluntary Support of Education. New York, NY.

Council for Aid to Education. (2006) 2005 Voluntary Support of Education. New York, NY: Author.

Cunningham, B.M. and Cochi-Ficano, C.K. (2002) The determinants of donative revenue flows from alumni of higher education: An empirical inquiry. The Journal of Human Resources 37 (3): 540–569.

Di Mento, M. (2006, June 2) How endowment of 247 major nonprofit organizations performed? The Chronicle of Higher Education, p. B3.

Ehrenberg, R.G. and Smith, C.L. (2001) What a Difference a Decade Makes: Growing Wealth Inequality among Ivy League Institutions, New York, NY. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 470 059.

Geiger, R. (1985) After the emergence: Voluntary support and the building of American research universities. History of Education Quarterly 25 (3): 369–381.

Hansmann, H. (1990) Why do universities have endowments? The Journal of Legal Studies 19: 3–42.

Leslie, L. and Ramey, G. (1988) Donor behavior and voluntary support for higher education institutions. The Journal of Higher Education 59 (2): 115–132.

Loessin, B.A., Duronio, M.A. and Borton, G.L. (1988) Understanding Fund-raising Effectiveness in Higher Education: Laying a Foundation. Final Report prepared for the Exxon Education Foundation. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. Working Paper No. 1.

Massy, W.F. (1990) Endowment: Perspectives, Policies, Management. Washington DC: Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.

Morrell, L.R. (2000, February) The true purpose of your endowment. NACUBO Business Officer: 42–45.

National Association of College and University Business Officers. (2006) 2005 NACUBO Endowment Study. Washington DC: National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Oster, S.M. (2003) Is There a Dark Side to Endowment Growth? In: F.K. Alexander and R.G. Ehrenberg (eds.) Maximizing Revenue in Higher Education, New Directions for Institutional Research, Vol. 119. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 81–90.

Patterson, F.D. (1976) The College Endowment Funding Plan. Washington DC: American Council on Education.

Swensen, D.F. (2000) Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Taylor, A.L. and Martin, J.C. (1995) Characteristics of alumni donors and non-donors at a Research I, public university. Research in Higher Education 36 (3): 283–302.

Thelin, J.R. (2004) Higher Education and the Public Trough: A Historical Perspective. In: E.P.S. John and M.D. Parsons (eds.) Public Funding of Higher Education: Changing Contexts and New Rationales. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 21–39.

Trow, M. (1988) American higher education: Past, present, and future. Educational Researcher 17 (3): 14–23.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2006) U.S. Census Bureau maps and cartographic resources. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau, from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/maps, accessed 30 December 2006.

U.S. News & World Report. (2006) How U.S. News ranks colleges. Washington DC: U.S. News & World Report. from http://www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/college/rankings/about/index_brief.php, accessed 12 November 2006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

1received her PhD in Educational Policy and Administration from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, and is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Accounting at the I-Shou University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, HL. The growth and stratification of college endowments in the United States. Int J Educ Adv 8, 136–151 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2009.10

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/ijea.2009.10