Abstract

This paper examines the effectiveness of international capital controls in India over time by analyzing daily return differentials in the nondeliverable forward (NDF) markets using the self-exciting threshold autoregressive (SETAR) methodology. The paper presents a narrative on the evolution of capital controls in India and calculates a new index of capital account liberalization using cumulative monthly changes in restrictions on inflows and outflows. It employs the de jure indices of changes in restrictions on capital inflows and outflows to identify particular policy episodes, and tests the de facto effects of restrictions by calculating deviations from covered interest parity (CIP) utilizing data from the three-month offshore nondeliverable rupee forward market. The paper estimates no-arbitrage bands for each episode using SETAR where boundaries are determined by transactions costs and by the effectiveness of capital controls. It finds that Indian capital controls are asymmetric over inflows and outflows, have changed at one stage from primarily restricting outflows to effectively restricting inflows; and that arbitrage activity closes deviations from CIP when the threshold boundaries are exceeded in all subperiods. Moreover, the results indicate a significant reduction in the barriers to arbitrage since 2009, suggesting that gradual liberalization of India's capital account has played an important role in integrating onshore and offshore markets. The paper also applies the methodology to the Chinese RMB NDF market and find that capital controls are strictly limiting capital inflows with the exception of two periods of regional and international financial turbulence. The intensity of Chinese controls varies over time, indicating discretion in the application of capital control policy but, unlike India, shows no sign of gradual relaxation or liberalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Studies that have estimated deviations from CIP as an indication of international financial market integration in various contexts include Frenkel and Levich (1975), Taylor (1989), Peel and Taylor (2002), Obstfeld and Taylor (2004) and others.

The SETAR model is a particular class of piece-wise autoregressive models and may be seen as a parsimonious approximation of a general nonlinear autoregressive model (Hansen, 2000).

Pasricha (2008), investigating interest rate differentials, also finds that India is de facto more open than de jure measures such as the Chinn-Ito index suggest.

Ma and others (2004) and Misra and Behera (2006) have used data from NDF markets to examine variations in deviations from CIP arbitrage conditions in India over time using simple summary statistics and qualitative methods, but not with more formal statistical modeling. (See Appendix II for differences in alternative measures of CIP deviations.) They find that smaller deviations from covered interest parity are an indication of greater capital account openness since the advent of India's capital control liberalization.

Most inter-dealer transactions in the NDF market are concentrated in two- to six-month maturities, and we follow Ma and others (2004) in focusing on the three-month maturity. We considered one- and three-month maturities, but focused on the latter, as better capturing significant transaction volume. The data on NDF contracts is from Bloomberg and the MIBOR rates and spot rates are from Global Financial Database and LIBOR rates are from Federal Reserve Board's online database.

Lipscomb (2005) provides a useful overview of NDF markets.

Although Misra and Behera's work is officially dated 2006, they include data for early 2007. The rupee NDF market reportedly grew further to U.S. $19 billion a day in April 2010, and U.S. $43 billion a year later, as reported in a newspaper opinion piece (www.business-standard.com/india/news/jamal-mecklai-has-rbi-lost-controlthe-rupee/441038/), but the data source is not cited.

To put these numbers in perspective, the growth seen in the USD/INR pair was close to the median growth in trades against USD for other large emerging markets (Brazil, China, Korea, and South Africa) for which the same BIS report provides data. For example, the USD/Brazilian Real, pair, which saw trading volumes growth from 5 billion USD in 2001 to 26 billion in 2010 and in South African rand, which saw the volumes grow from 7 billion USD to 24 billion USD over the same period.

In August 2008, the Reserve Bank of India allowed trading on a domestic currency futures exchange to begin. Prior to this innovation, trading for those permitted to do so was over-the-counter. Restrictions remain on participation in the exchange; for example, only Indian residents can participate.

In practice, the formula is modified a bit, because each forward contract is valid for a given number of days (depending on the maturity of the contract, in this case, 3-months, but also on the value and settlement dates for the contract) and the LIBOR rates are annualized, i.e. refer to percentage per annum. We computed the actual number of days in each forward contract based on the market conventions about the forward contracts, de-annualized the LIBOR rate for that number of days (assuming 360 days in the year, as done in LIBOR) and expressed the de-annualized rate in percentage points. The resulting r is then re-annualized based on the number of days for which it is computed and assuming 365 days in the year and is expressed as a percentage.

If forward rates are determined primarily by expected future currency needs from importers and exporters, rather than by pure arbitrage by currency traders or others, the direction of deviation from CIP can be an indicator of market expectations with respect to future currency appreciation or depreciation. Patnaik and Shah (2005) give examples in India in 1993–94 and 1997–98 where expectations as implied by the direction of CIP deviation turned out to be incorrect. However, their regression analysis indicates that, barring some outlier events, expectations of the direction of currency movements as implied by CIP deviations have been correct on average. A related point is that variation in deviations from CIP may reflect changing counterparty risk premiums. However, these risk premiums are unobservable: our maintained hypothesis that the source of variation is changes in controls is consistent with the data and our estimated model.

For example, the period for repatriation of export proceeds currently stands at 12 months. This was extended from six months in March 2011, but the extension is operative only through September 2012. Restrictions on net open positions of banks, often used to serve current account transaction needs of clients, were tightened in December 2011 in response to a sharp depreciation of the rupee, and were begun to be relaxed in February and April 2012.

Jadhav (2003) provides a useful “insider” review of India's experience with capital controls and capital account liberalization through 2002.

This committee, like its predecessor, also commented on desired complementary changes in fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate policies.

Our main numerical analysis omits FDI changes for reasons described in the main text.

Patnaik and Shah (2011) suggest that a unified manual on Indian capital controls would run into many thousands of pages.

Schindler's (2009) measure indicates that capital controls actually became more restrictive in India between 1998 (the beginning of our sample) and 2005 (the end of Schindler's sample). During this period, his index of overall capital account restrictiveness rose from 0.83 to 0.96, index of restrictions on capital inflows increased from 0.83 to 0.92, and index of restrictions on capital outflows rose from 0.83 to 1.0, where zero indicates completely free of restrictions and unity indicates completely restricted capital account. By the Chinn-Ito measure, in the most recent update posted on the website (www.web.pdx.edu/~ito/Chinn-Ito_website.htm), India's restrictiveness on capital account transactions has not changed between 1970 and 2010. (The measure stands at −1.16, indicating that capital account transactions in India are among the most restrictive in the world.)

This study uses the three-month MIBOR to measure domestic interest rates. This matches well with the three-month LIBOR rate. An alternative interest rate is the 31-day T-Bill implicit yield (Ma and McCauley, 1998) and the implied onshore yield derived from deliverable forward rates has also been used (Misra and Behera, 2006). We calculated the implied three-month onshore yield using deliverable forward rates. The correlation with our MIBOR measure was 0.60, but these implicit interest rates were much lower than the MIBOR measure (averaging 2.0 percent over the full sample period, compared with the MIBOR average of 7.5 percent). The Misra-Behera implied onshore yield approach seems conceptually problematic, and the levels of the interest rate it implies are not realistic. The low level means that the CIP deviations calculated from the Misra-Behera formula can easily differ in sign from those calculated in this paper. A further comparison of different measures of CIP deviations is in Appendix II.

In related work, Hutchison and others (2010), we used Bai-Perron structural break tests on weekly data of implied yield differentials and found that break dates lay in January 2003 and April 2005, for data that ended in January 2008. The estimated no-arbitrage bands for these periods follow a similar pattern to the bands estimated here.

Zeileis, Shah, and Patnaik (2010) suggest that a structural break in the degree of exchange rate rigidity occurred in May 2003, with the exchange rate becoming more flexible.

Moody's upgraded India's foreign currency sovereign longer-term debt to investment grade in January 2004, Fitch in August 2006 and Standard and Poor's (S&P) in January 2007. Fitch and S&P also upgraded India's local currency bond ratings to investment grade at the same time that they upgraded its foreign currency ratings. These changes are important as the sovereign ratings are often the ceiling for private sector ratings and some financial institutions are restricted to investing only in investment grade debt. The improvement in ratings would increase the availability of arbitrage funds in Indian markets.

As the names indicate, the SETAR model is a special case of the TAR model, in which regime-switch thresholds depend on lagged values of the autoregressive variable itself.

Pasricha's study (2008) uses SETAR models to measure deviations from interest rate parity in 11 emerging market economies and, outside of crisis periods, assumes parameter stability. Levy Yeyati and others (2006) use data from nine emerging market economies to examine the ratio between the domestic and the international market price of cross-listed stocks, thereby providing a valuable measure of international financial integration. Note that the latter paper uses the general term TAR, but the model is in fact a SETAR model.

Thus, 5 percent was trimmed on each side. Every actual value of the CID between the 5th and 95th percentiles was used as a possible threshold in the unrestricted model. In addition, the number of observations in each regime was restricted to be at least 5 percent of sample.

Where the model selected is a 1-threshold model, the three-regime framework may still apply, if the other threshold is interpreted to be beyond the observed deviations.

This result is somewhat different from Ma and McCauley (2008) who regress the mean absolute deviations (weekly data) from CIP (12-month instruments) on three dummy variables representing different periods of time. Their most recent period (July 2005-June 2008) has the lowest coefficient estimate, that is, the lowest mean absolute value.

Negative AR parameters for outer regimes are interpreted to mean instantaneous arbitrage.

An AR (1) parameter less than unity indicates mean reversion, that is, CIP deviations outside of the band are eliminated. A zero AR (1) parameter indicates immediate reversion to the band.

The negative AR (1) coefficient (−0.55) below the boundary indicates deviations in an outer regime lasting less than one day.

The data on RBI interventions is available on a monthly basis from RBI's website, www.rbi.org.in. The information is published in the RBI Bulletin in the Trade and Balance of Payments section, in the Table on Sale/Purchase of U.S. Dollar by RBI.

Another episode where strict controls on capital outflows can be measured is the first sub-sample, January 1999-August 2001. While the LR test does not reject a 1-Threshold model in this sub-sample, both regimes have AR coefficients greater than 1. We interpret this as the entire sample being under no-arbitrage regimes, with effectively no “outside” zone, and the arbitrage zone lying somewhere outside of the observed deviations. Another factor to keep in mind while interpreting these results is that the number of observations in this sub-sample is small (only 127 over a 2.5 year period) and the observations are missing for several days at a stretch.

Tables A1 and A2 in the appendix present results for annual SETAR estimates for both India and China. This analysis does not rely on our precise periodization, and the results are broadly consistent with the results and interpretation presented in the main text and tables.

The database used in this paper is an extended version of the database compiled in Pasricha (2012). Further details are provided in this source and are also available from the authors upon request.

If a major policy announcement takes place and includes measures related to several categories above, each measure is classified in each category in which it belongs and is counted separately. For example, on March 10, 2003, two different changes were announced—overseas corporate bodies (OCBs) were no longer allowed to purchase securities under the portfolio investment scheme, and OCBs that are unincorporated entities were no longer allowed to make new investments under the FDI scheme. These changes were counted separately in the database, and the second change was not included in the index as it related to FDI only.

Examples of the other measures that could not be classified as inflow or outflow measures include limits on net open foreign exchange positions of financial institutions, ban on use of foreign currency in special economic zones, restrictions on transactions that would constitute at once an inflow and outflow, for example use of external borrowing to invest abroad, and so on.

References

Baba, N., and I. Shim, (2010), “Policy Responses to Dislocations in the FX Swap Market: The Experience of Korea,” Bank for International Settlements Quarterly Review, (June), pp. 29–39.

Bai, J., and P. Perron, (2003), “Computation and Analysis of Multiple Structural Change Models,” Journal of Applied Econometrics, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 1–22.

Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department, (2010), “Triennial Central Bank Survey: Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in April 2010,” Annex Tables (November 2010).

Chinn, Menzie, and Hiro Ito, (2008), “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 309–322.

Cheung, Y.W., D. Tam, and M.S. Yiu, (2008), “Does the Chinese Interest Rate Follow the U.S. Interest Rate?” International Journal of Finance and Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 53–67.

Frenkel, J.A., and R.M. Levich, (1975), “Covered Interest Arbitrage: Unexploited Profits?” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 83, No. 2, pp. 325–338.

Glick, R., and M. Hutchison, (2009), “Navigating the Trilemma: Capital Flows and Monetary Policy in China,” Journal of Asian Economics, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 205–224.

Hansen, Bruce E., (1996), “Inference When a Nuisance Parameter is Not Identified under the Null Hypothesis,” Econometrica, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 413–430.

Hansen, Bruce E., (1999a), “Threshold Effects in Non-Dynamic Panels: Estimation, Testing, and Inference,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 93, No. 2, pp. 345–368.

Hansen, Bruce E., (1999b), “Testing for Linearity,” Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 13, No. 5, pp. 551–576.

Hansen, Bruce E., (2000), “Sample Splitting and Threshold Estimation,” Econometrica, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 575–603.

Hutchison, M., J. Kendall, G. Pasricha, and N. Singh, (2010), “Indian Capital Control Liberalization: Evidence from NDF Markets,” National Institute of Public Finance and Policy Working Paper No. 2009-60.

Jadhav, Narendra, (2003), “Capital Account Liberalisation: The Indian Experience,” Available via the Internet: www.imf.org/external/np/apd/seminars/2003/newdelhi/jadhav.pdf.

Levy Yeyati, Eduardo, Sergio L. Schmukler, and Neeltje Van Horen, (2006), “International Financial Integration through the Law of One Price,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3897.

Lipscomb, Laura, (2005), An Overview of Non-Deliverable Foreign Exchange Forward Markets (Federal Reserve Bank of New York), Unpublished document, May.

Ma, G., and R. McCauley, (2007), “Do China's Capital Controls Still Bind? Implications for Monetary Autonomy and Capital Liberalization,” Working Paper No. 233 (Bank of International Settlements, August).

Ma, G., and R. McCauley, (2008), “Efficacy of China's Capital Controls: Evidence from Price and Flow Data,” Pacific Economic Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 104–123.

Ma, G., C. Ho, and R. McCauley, (2004), “The Markets for Non-Deliverable Forwards in Asian Currencies,” BIS Quarterly Review (June), pp. 81–94.

Misra, Sangita, and Harendra Behera, (2006), “Non-Deliverable Forward Exchange Market: An Overview,” Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 25–55.

Obstfeld, M., and A.M. Taylor, (2004), Global Capital Markets: Integration, Crisis and Growth (Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press).

Ostry, J.D., A.R. Ghosh, K. Habermeier, M. Chamon, M.S. Qureshi, and D.B.S. Reinhardt, (2010), “Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls: IMF Staff Position Note,” February.

Pasricha, Gurnain, (2008), “Financial Integration in Emerging Market Economies,” Department of Economics Working Paper No. 641 (Santa Cruz: University of California).

Pasricha, Gurnain, (2012), “Recent Trends in Measures to Manage Capital Flows in Emerging Economies,” North American Journal of Economics and Finance, forthcoming, DOI: 10.1016/j.najef.2012.03.003.

Patnaik, I., and A. Shah, (2007), “India's Experience with Capital Flows: The Elusive Quest for a Sustainable Current Account Deficit,” in Edwards, S. (ed), “Capital Controls and Capital Flows in Emerging Economies: Policies, Practices and Consequences”, NBER Research Conference Volume, pp. 609–644, University of Chicago Press, May 2007.

Patnaik, I., and A. Shah, (2010), “Why India Choked When Lehman Broke,” in India Policy Forum, Vol. 6, (New Delhi: NCAER and Brookings Institution).

Patnaik, I., and A. Shah, (2011), “Did the Indian Capital Controls Work as a Tool of Macroeconomic Policy?” NIPFP Working Paper 2011-87.

Peel, D.A., and M.P. Taylor, (2002), “Covered Interest Rate Arbitrage in the Inter-war Period and the Keynes-Einzig Conjecture,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 51–75.

Potter, Simon, (1999), “Nonlinear Time-Series Modeling: An Introduction,” FRB of New York Staff Report No. 87.

Prasad, E., and S. Wei, (2005), “The Chinese Approach to Capital Inflows: Patterns and Possible Explanations,” IMF Working Paper No. 05/79.

Schindler, Martin, (2009), “Measuring Financial Integration: A New Data Set,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 222–238.

Sinha, U.K., (2010), Working Group on Foreign Investment, Committee report, (New Delhi: Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance).

Tarapore Committee, (1997), Report of the Committee on Capital Account Convertibility (Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India), May 30.

Tarapore Committee, (2006), Report of the Committee on Fuller Capital Account Convertibility (Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India), July 31.

Taylor, M.P., (1989), “Covered Interest Arbitrage and Market Turbulence,” Economic Journal, Vol. 99, pp. 376–391.

Tong, H., (1978), “On a Threshold Model,” in Pattern Recognition and Signal Processing, ed. by C.H. Chen (Amsterdam: Nijhoff and Noordhoff).

Zeileis, A., A. Shah, and I. Patnaik, (2010), “Testing, Monitoring, and Dating Structural Changes in Exchange Rate Regimes,” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, Vol. 54, No. 6, pp. 1696–1706.

Additional information

*Michael Hutchison is a Professor of Economics at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Gurnain Pasricha is a Senior Analyst at Bank of Canada. Nirvikar Singh is a Professor of Economics at University of California, Santa Cruz. The authors thank Ron Alquist, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Robert McCauley, Rhys Mendes, Ila Patnaik, Sergio Schmukler, Ajay Shah, Matthieu Stigler, and two anonymous referees for very helpful suggestions. Support for this project from the NIPFP-DEA Program on Capital Flows and their Consequences and collaboration on related work with Jake Kendall is gratefully acknowledged. Kristina Hess, Rose Chen, and Jamshid Mavalwalla provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed in the paper are of the authors—no responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank of Canada.

Appendices

Appendix I

Measures on the Capital Account and Their Classification

In order to analyze the evolution of capital flows policies in India, we analyze all changes in regulation influencing capital account transactions. The measures include:

-

capital controls, that is, measures on the capital account that differentiate based on residency of the entity undertaking the transaction;

-

currency-based measures, that is, measures that differentiate based on currency of transaction

The measures include regulations applicable to the financial sector that are relevant for capital transactions. The main source of data is the IMF's Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER). The AREAER provides information on member countries’ exchange arrangements, exchange and trade restrictions and capital transactions. We focus on the capital transactions section which includes regulations applicable to the financial sector that are relevant for capital transactions. The AREAER data is supplemented with information on similar measures from RBI and DIPP websites, news sources, and other research papers.Footnote 33

The IMF's AREAER breaks down the broad category, capital transactions into the following subsections:

-

1

Controls on capital and money market instruments:

-

a)

Controls on capital market securities: further classified into “controls on shares or other securities of a participating nature” and “banks or other debt securities”

-

b)

Controls on money market instruments

-

c)

Controls on collective investment schemes

-

a)

-

2

Controls on derivatives and other instruments

-

3

Controls on Credit Operations:

-

a)

Commercial Credits

-

b)

Financial Credits

-

c)

Guarantees, sureties and financial backup facilities

-

a)

-

4

Controls on direct investment

-

5

Controls on liquidation of direct investment

-

6

Controls on real estate transactions

-

7

Controls on personal capital transactions

-

8

Provisions specific to the financial sector:

-

a)

Provisions specific to commercial banks and other credit institutions, which include open foreign exchange position limits and other provisions

-

b)

Provisions specific to institutional investors

-

a)

We take a quantitative approach to analyzing policy measures, examining the number of policy measures on the capital account that India has imposed since 1998. In doing this, we follow the IMF's Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER), which carries out an analysis based on the number of changes in restrictive measures on capital account transactions. The number of measures is not sufficient to judge the impact of the measures or to differentiate them by their degree of restrictiveness. However, most measures in the database are of relatively homogeneous magnitude, as major policy announcement are broken up into the number of categories of transactions they influence and each change is counted separately.Footnote 34 For these reasons, this numerical approach does provide useful information about the overall direction of policy, and about the attempts to liberalize or to restrict international capital account transactions.

We classify the measures into the following categories:

-

1

Whether the measure (or change) impacts capital inflows (I) or outflows (O) or cannot be clearly identified as affecting only one of these categories (other).Footnote 35

-

2

Whether the change represents an easing (E) or tightening (T) of policy or a neutral/institutional change. We assign a numerical value of +1 to each easing measure and of −1 to each tightening measure.

We have information on each change as of the date of announcement. The monthly index of inflows is defined as the cumulative sum over all past easing less tightening measures. Algebraically, the Inflows index in month m is:

where N t E is the number of inflows easing measures announced in month t and N t T is the number of inflows tightening measures announced in month t. The outflows index is analogously defined.

We exclude from the indices all changes that relate to FDI, as changes in FDI policy are largely independent of the motives of macroeconomic management including maintaining exchange rate stability or managing “hot money” inflows. Further, the non-FDI related changes are likely to have the most immediate impact on arbitrage and on covered interest differentials.

Appendix II

Measuring Deviations from Covered Interest Parity

Several methods to measure deviations from CIP from been employed recently in the context of India. These methods may vary by how the onshore yield (or implied yield) is calculated, how the offshore implied yield is calculated, by the choice of the domestic and foreign interest rates, and by the maturity of the instruments.

-

1)

As discussed in the text, our method (Hutchison-Pasricha-Singh, HPS) measures deviations from CIP as the domestic interest rate (Mumbai Interbank Offer Rate, MIBOR) less the offshore implied domestic yield using NDF (F N ) We employ the three-month MIBOR rate as the domestic interest rate as it is directly comparable to the three-month USD LIBOR rate used by almost all studies. This measure is the same as Ma and others (2004), with the exception that they use the 91-day T-Bill auction yield as the domestic interest rate. We describe in the text the advantages of employing the unrestricted offshore NDF rate to measure CIP deviations.

-

2)

A second measure employed by Baba and Shim (BIS, 2010) measures deviations from CIP as the onshore implied foreign interest rate (using the three-month MIBOR rate and the onshore deliverable forward rate (F)) less the foreign interest rate (i*). That is, they measure the implied onshore foreign yield less the observed foreign interest rate. As in our study, they also use the USD LIBOR and MIBOR rate. (Baba and Shim also define the exchange rate as the USD/rupee rate, rather than the rupee/USD rate. The formula below simply rewrites the equation to be consistent with our definition of the exchange rate.)

-

3)

A third measure, employed by Misra and Behera (2006), measures deviations from CIP as the implied onshore yield (using F) less the implied offshore yield (using NDF, F N ). They also use the USD LIBOR rate.

Algebraically, these three measures of CIP deviations may be written as:

where F is the onshore deliverable forward rate, S is the spot rate, i is the domestic interest rate, i* is the USD interest rate, and F N is the NDF rate. All exchange rates are expressed as domestic currency units per USD, and all instruments (other than S) are for a three-month maturity.

The definition of the CIP differential in terms of domestic yield (HPS) or foreign yield (Baba-Shim) is not important empirically and, if using the same forward rate (F), the two equations are related by HPS=(F/S)*BIS. (Essentially, the HPS measures borrowing 1 rupee, investing this amount in USD, and measuring the USD return. The BIS measures borrowing 1 USD, investing this amount in rupees and measuring the return in rupees). In a high inflation environment, a substantial forward premium could emerge and give somewhat divergent measures but always the same direction of CIP deviations. However, in India during our sample period, these divergences are not large. By contrast, the significant difference between HPS and Baba-Shim is the use of the offshore NDF rate or the onshore forward rate. This is a critical difference and, during the global financial crisis, gave quite different measures of CIP deviations.

On the other hand, the only difference between HPS and Misra-Behera is the use of the domestic interest rate (HPS) as opposed to the implied domestic yield using the onshore forward rate (Misra-Behera).

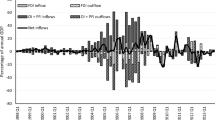

The differences between the three measures may be substantial, mainly reflecting movements in the onshore forward or offshore NDF markets during turbulent periods which in turn may be influenced by “dislocations” (Baba and Shim, 2010), the absence of liquidity and dramatic shifts in risk assessments. Figure B1 shows how the three measures have tracked since 1998. (Daily data is presented as monthly moving averages for ease of visual presentation). The figure shows that the HPS and Misra-Behera measures shadow each other closely from early 1999 until mid-2003 showing large differentials (domestic yields are low compared with covered yields abroad), while the Baba-Shim measure shows almost no CIP deviations during this period. From 2003 onward, HPS and Baba-Shim track each other reasonably closely with the notable exceptions of several months spanning 2005–06 and several days in 2008 during the financial crisis. HPS and Misra-Behera measures diverge significantly in mid-2003, but again track closely for most of the sample after late 2004. The exception is during the run-up to the financial crisis (late 2007 to mid-2008) when the HPS and Baba-Shim measures showed substantial positive CIP deviations while the Misra-Behera measure fluctuated around zero.

Our article demonstrates that substantial structural changes have occurred in the administrative use of capital controls, and other institutional market changes have also occurred during our full sample period which can account for some of the systemic divergences between onshore and offshore market measures of CIP. The sharp deviation in the HPS (and Misra-Behera) from the Baba-Shim measures for a week-long period during the financial crisis, however, must be attributable to significant market dislocation, liquidity shortages and a sharp segmentation between onshore forward market and offshore NDF market for Indian rupee. The forward premium (USD) climbed significantly in the NDF market, pushing the CIP differential sharply negative by the HPS and Misra-Behera measure, while the domestic forward market premium declined markedly (see Patnaik and Shah, 2009–10), sharply increasing the CIP differential by the Baba-Shim measure. It is interesting to note that this price divergence also occurred for the Chinese RMB onshore and offshore markets. (Data available upon request.)

Some explanations for the decline in the domestic forward premium are given in Patnaik and Shah (2009–10) and Baba and Shim (2010), essentially attributing this phenomenon to a USD liquidity shortage that increased domestic yields substantially relative to yields abroad. Patnaik and Shah also argue that the forward market became completely decoupled from the spot foreign exchange rate market for several days, leading to extreme market segmentation. What is not clear, however, is why the opposite developments occurred in the offshore NDF markets and which measure of CIP deviations are most accurate during this period of large market fluctuations and dysfunction.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to investigate the underlying institutional causes of these price discrepancies, clearly going beyond the administration of capital controls. However, we believe that it is an important, albeit very short-term, phenomenon that sheds light on the liquidity, risk and institutional differences in the operation of onshore and offshore markets that is on our future research agenda.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hutchison, M., Pasricha, G. & Singh, N. Effectiveness of Capital Controls in India: Evidence from the Offshore NDF Market. IMF Econ Rev 60, 395–438 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2012.11

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2012.11