Abstract

Supply-side policies can play a role in fighting a low aggregate demand that traps an economy at the zero lower bound (ZLB) of nominal interest rates. Reductions in mark-ups or future increases in productivity triggered by supply-side policies generate a wealth effect that pulls current consumption and output up. Since the economy is at the ZLB, increases in interest rates do not undo this wealth effect. The paper illustrates this mechanism with a New Keynesian model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Technically, Euro zone countries are not at the ZLB, since the nominal interest rates are slightly positive. However, the ECB will not let the short-term nominal interest rate fall further. The rigidity of the nominal interest rate is all we need to deliver the results here. In fact, having a slightly positive nominal interest rate when the natural interest rate should be negative makes the situation worse.

Monetary policy can fix that problem by increasing the long-run price level, either through temporarily higher inflation (Krugman, 1998; Eggertsson and Woodford, 2003) or through lump-sum transfers of cash (Auerbach and Obstfeld, 2005). Similarly, as shown by Correia and others (2010), fiscal policy can neutralize the ZLB and achieve first best by using taxes to replicate the optimal price path.

One must also be aware, though, of the political-economic barriers to the introduction of structural reforms. Our argument highlights a benefit of overcoming those barriers that the literature has not explored: its expansionary effect on current aggregate demand.

Rogoff (1998), in his discussion of Krugman’s paper, makes en passant the same point that future productivity gains are a solution to the ZLB problem, but without linking it to a policy strategy.

Aruoba and Schorfheide, 2011, for example, estimate η=31.8. Remember that 1/η is the elasticity of money demand to interest rates, which most empirical studies find is small.

With the more common formulation, the results are nearly identical but harder to evaluate.

This is another argument against selecting the positive root: with that positive root, firms will raise prices less when demand is higher. This response is less plausible than the standard Keynesian argument of higher demand leading to higher prices.

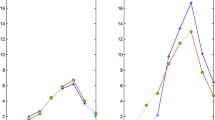

For this graph, and only for illustrative purposes, we chose η=5, β=1, ɛ=5, φ=50, p1=1, m=0.95, A1=A2=1.

We thank one of our referees for suggesting this interpretation.

For this graph, we chose the same parameter values as before, plus

.

.For this graph, we chose the same parameter values as before, plus ɛhigh=10.

For this graph, we chose the same parameter values as before, plus mhigh=0.96.

References

Aruoba, S.B. and F. Schorfheide, 2011, “Sticky Prices versus Monetary Frictions: An Estimation of Policy Trade-offs,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 60–90.

Auerbach, A.J. and M. Obstfeld, 2005, “The Case for Open-Market Purchases in a Liquidity Trap,” American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 110–37.

Blanchard, O. and F. Giavazzi, 2003, “Macroeconomic Effects of Regulation and Deregulation in Goods and Labor Markets,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, No. 3, pp. 879–907.

Christiano, L., M. Eichenbaum, and C.L. Evans, 2005, “Nominal Rigidities and the Dynamic Effects of a Shock to Monetary Policy,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 113, No. 1, pp. 1–45.

Cochrane, J., 2013, “The New-Keynesian Liquidity Trap,” NBER Working Paper 19476.

Correia, I., E. Farhi, J.P. Nicolini, and P. Teles, 2010, “Unconventional Fiscal Policy at the Zero Bound,” Harvard University (mimeo).

David, P., 1990, “The Dynamo and the Computer: An Historical Perspective on the Modern Productivity Paradox,” American Economic Review, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 355–61.

DeLong, J.B. and L.H. Summers, 1986, “Is Increased Price Flexibility Stabilizing?,” American Economic Review, Vol. 76, No. 5, pp. 1031–1044.

Eggertsson, G.B., A. Ferrero, and A. Raffo, 2014, “Can Structural Reforms Help Europe?,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 61, No. January, pp. 2–22.

Eggertsson, G.B. and M. Woodford, 2003, “The Zero Bound on Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 139–235.

Forni, L., A. Gerali, and M. Pisani, 2010, “Macroeconomic Effects of Greater Competition in the Service Sector: The Case of Italy,” Macroeconomic Dynamics, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 677–708.

Ilzetzki, E., E.G. Mendoza, and C.A. Végh, 2010, “How Big (Small?) Are Fiscal Multipliers?” NBER Working Papers 16479.

Kleiner, M.M., A. Marier, K.W. Park, and C. Wing, 2014, “Relaxing Occupational Licensing Requirements: Analyzing Wages and Prices for a Medical Service,” NBER Working Papers 19906.

Krugman, P.K., 1998, “It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 137–206.

Mankiw, N.G. and M.C. Weinzierl, 2011, “An Exploration of Optimal Stabilization Policy,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 209–72.

Prados de la Escosura, L., J.R. Rosé, and I. Sanz Villarroya, 2011, “Economic Reforms and Growth in Franco’s Spain,” Revista de Historia Económica, Journal of lberian and Latin American Economic History, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 45–89.

Rogoff, K., 1998, “Discussion of: It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 137–206.

Werning, I., 2011, “Managing a Liquidity Trap: Monetary and Fiscal Policy,” MIT (mimeo).

Additional information

*Jesús Fernández-Villaverde is Professor of Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, Pablo Guerrón-Quintana is Economic Advisor and Economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, and Juan Rubio-Ramírez is Professor of Economics at Duke University. The authors thank Mike Woodford for an important clarification and Jorge Juan, Jim Nason, and Ivan Werning, the editor, and two referees for insightful comments. Beyond the usual disclaimer, we must note that any views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, or the Federal Reserve System. Finally, the authors also thank the NSF for financial support.

.

.