Abstract

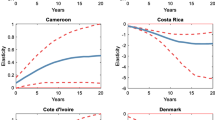

To maintain price and exchange rate stability, many emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs) de facto peg their exchange rates, intervening in the foreign exchange markets, but without formally committing to a peg. But in doing so, are they foregoing important benefits in terms of lower inflation? We argue that the de jure commitment, by making exit more costly, imparts greater credibility, which better anchors inflationary expectations, thereby leading to lower inflation than de facto pegging alone. Our empirical analysis, based on a novel data set of IMF de jure and de facto exchange rate regime classifications for 146 EMDCs over 1980–2010, finds that inflation is indeed lower—especially in emerging markets—by some 4 percentage points when the central bank both de jure commits and de facto pegs the exchange rate than when it de facto pegs alone. Thus, analogous to inflation targeting, where the formal commitment to the framework is thought to help anchor inflationary expectations, the de jure commitment to the peg may also be important to reap the full price-stability benefits of pegs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although IT has been gaining popularity in the EMDCs since the mid-1990s, it still constitutes a small proportion (averaging about 10 percent in the last decade) of EMDCs, some of which intervene frequently in the foreign exchange market despite the IT framework. By contrast, the proportion of de facto peggers (with or without a de jure commitment) averages over 50 percent of the sample in 2000–10.

That the de jure commitment to peg may be costlier (in terms of a higher crisis propensity) is certainly a possibility. Several studies show that pegs are more prone to financial/currency crises (for example, Bubula and Ötker-Robe, 2003; Ghosh, Gulde, and Wolf, 2003; Rogoff and others, 2003; and Ghosh, Ostry, and Qureshi, 2014), but do not distinguish between de jure and de facto pegs, and de facto pegs alone. While a formal treatment of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper, which focuses on any additional disinflationary benefits of formal commitment when a de facto peg exists, we explore below the duration and exit properties of both types of pegs to assess the extent of the possible inflation-crisis trade-off.

Using both de jure and de facto classifications, Guisinger and Singer (2010) however find no association between pegs and inflation under either regime. This may be because their sample comingles advanced and developing economies, and earlier studies typically find no association between regimes and inflation performance in advanced economies.

Indeed, even the early studies that used de jure classifications differentiated between countries that maintained their de jure peg and those that (de facto) allowed frequent movements of the parity, finding that the latter had little or no inflation advantage over floats (see, for example, Ghosh and others, 1997).

Calvo and Reinhart (2002) argue that countries de facto peg because exchange rate volatility could affect their risk premium on borrowing, and could also give rise to dollarization. Rogoff and others (2003) suggest that de facto pegs arise because of currency mismatch and balance sheet concerns, and/or fear of Dutch disease (in the face of potentially large appreciations). Levy-Yeyati and Sturzenegger (2005) contend that de facto pegs not backed by words reflect a “fear of pegging.” Alesina and Wagner (2006) suggest that countries de facto peg to avoid wide exchange rate fluctuations, while retaining the flexibility to respond to idiosyncratic shocks. By contrast, Genberg and Swoboda (2005) suggest that fear of floating may not indicate the breaking of any commitment at all, but rather reflect exchange rate stability achieved through optimally chosen monetary policies.

The closest empirical study to ours is Levy-Yeyati and Sturzenegger (2001) who, for their sample (which ends in 1999 and therefore may not have many “stealth peggers”), find that de jure pegging has no independent impact unless the de facto peg has been in place for at least five years.

Updating Cooper’s (1971) study, for example, Frankel (2005) finds that 29 percent of prime ministers or chief executives and 58 percent of finance ministers or central bank governors lost office within one year of a devaluation (against unconditional probabilities of 21 and 36, respectively).

On the other end, the central bank may be more hesitant to opt for discretionary changes to the parity under a pure peg, when the exchange rate deviates from “fundamentals”—for fear of signaling a lack of commitment and triggering a speculative attack. Warranted exchange rate adjustment may thus be postponed until pressure builds up to the extent that a large and abrupt change in the parity is unavoidable.

Argentina’s currency board implemented in 1991 was instrumental in bringing down inflation (after decades of high inflation and failed stabilizations), but the regime later became a straitjacket, impeding the necessary external adjustment after the EME crises in the 1990s. The very cost of exiting the regime meant that it was maintained too long, until an even costlier exit was forced on the country by markets withdrawing financing.

If, however, purchasing power parity holds for all goods, then inflation would not differ between pure and stealth pegs, as in both regimes inflation would be pinned down by purchasing power parity as long as the (pure or stealth) peg is maintained.

To take into account hyperinflation observations, the inflation rate is transformed as π/(1+π) (see the online appendix for variable descriptions and data sources).

Specifically, real GDP growth and trade openness are expected to lower inflation by raising money demand and increasing the cost of monetary expansions, respectively; central bank independence (lower turnover rate) is likely to lower inflation; broad money growth and fiscal deficit (with direct monetization or increased aggregate demand pressures) are expected to increase inflation; while the effect of terms-of-trade shocks may depend on how the aggregate supply and cost structure of the economy are affected (see, for example, Romer, 1993; Ghosh, Gulde, and Wolf, 2003; and Rogoff and others, 2003).

Recognizing the possible endogeneity between the control variables and inflation, we estimate all regressions using two-stage least squares approach where lagged values for real GDP growth, fiscal balance, and money growth are used as instruments. We address the endogeneity between pegs and inflation more comprehensively in Section III below. Considering the long-time dimension of the data and possible correlation in the error term, we cluster standard errors at the country level.

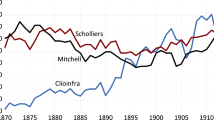

Ghosh, Gulde, and Wolf (2003) and Shambaugh (2004) base their de facto classifications on the behavior of the nominal exchange rate; Reinhart and Rogoff (2004) consider nominal exchange rate behavior as well as information on parallel market rates; whereas Levy-Yeyati and Sturzenegger (2005) consider nominal exchange rate, reserves, and interest rate behavior. Ghosh, Gulde, and Wolf (2003) and Rogoff and others (2003) review these classifications in detail.

The IMF de facto classification has been extended backwards for the period 1990–2000 by Bubula and Ötker-Robe (2003), and further backward covering the 1980s by Anderson (2008).

The conventional peg category includes both pegs to single currency and to a basket of currencies. In the robustness section, we experiment with a broader classification of pegs, which, in addition to categories (i)–(iii), also includes horizontal bands and crawling arrangements (categories (iv)–(vi)).

We focus on EMDCs as they are more likely to benefit from importing credibility (by pegging to a strong anchor currency) than advanced economies, which tend to have credible policy institutions of their own. Our EMEs comprise countries that are included either in JP Morgan’s Emerging Market Bonds Index (EMBI) or in the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Emerging Markets Index (excluding those classified as advanced economies by the IMF’s World Economic Outlook). The list of countries included in the sample is provided in the online appendix.

These statistics are computed taking the beginning of the sample (1980) as the first peg year, but excluding ongoing peg episodes in 2010. Including the latter leads to even starker differences: 58 percent of pure pegs last at least five years, whereas only 19 percent of stealth pegs last as long.

Retaining all observations and using one-period lagged regime; or considering the year of peg exit, and the year immediately following a peg exit, as a pegged regime (instead of a float) so as not to “contaminate” float observations with high inflation when a country is forced out of a peg, yields similar results.

This is analogous to the institutional setup of an IT framework, which is argued to contain inflationary expectations through formal announcements. Genberg and Swoboda (2005) note that the emphasis on de facto exchange rate regime classification has often implied that the de jure classification is largely irrelevant. By contrast, in other areas of economic policy, particularly monetary policy, effective communication of intention is viewed as essential. One may argue, however, that the effect of official commitments on inflation should be conditional on central bank’s credibility—with greater credibility implying a larger confidence effect, and vice versa. To check whether this holds empirically, we estimate Equation (1) by including an interaction term between pure pegs and the central bank turnover variable, but find it to be statistically insignificant.

Currency crises are defined, following Frankel and Rose (1996), as annual nominal depreciation of the currency of at least 30 percent that is also at least a 10 percentage point increase in the annual rate of depreciation. As currency crisis may influence inflationary expectations in the near term, thereby affecting inflation itself, we only consider crises in the sufficiently distant past (that is, in the last 5–10 years).

The probit pertains to the choice of pure peg vs. all other regimes and stealth peg vs. all other regimes; a separate question is the choice between a pure peg and a stealth peg. The choice of a pure peg (as opposed to a stealth peg) depends significantly on, among others, whether the country has experienced a currency crisis in the past, and whether it has a more independent central bank.

References

Alesina, A. and A. Wagner, 2006, “Choosing (and Reneging on) Exchange Rate Regimes,” Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 770–99.

Anderson, H., 2008, “Exchange Policies before Widespread Floating (1945–89),” mimeo (Washington DC, International Monetary Fund).

Barro, R. and D. Gordon, 1983a, “A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural-Rate Mode,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 91, No. 4, pp. 589–610.

Barro, R. and D. Gordon, 1983b, “Rules, Discretion, and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 101–121.

Bubula, A. and I. Ötker-Robe, 2003, “Are Pegged and Intermediate Regimes More Crisis Prone?” IMF Working Paper 03/223 (Washington DC, International Monetary Fund).

Calvo, G. and C. Reinhart, 2002, “Fear of Floating,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 117, No. 2, pp. 379–408.

Cooper, R, 1971, “Currency Devaluation in Developing Countries,” Essays in International Finance No. 86 (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University).

Frankel, J., 2005, “Mundell-Fleming Lecture: Contractionary Currency Crashes in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 149–92.

Frankel, J. and A. Rose, 1996, “Currency Crashes in Emerging Markets: An Empirical Treatment,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 41, No. 3–4, pp. 351–66.

Genberg, H. and A. Swoboda, 2005, “Exchange Rate Regimes: Does What Countries Say Matter?,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, Special Issue, pp. 129–41.

Ghosh, A., A. Gulde, J. Ostry, and H. Wolf, 1997, “Does the Nominal Exchange Rate Regime Matter?” NBER Working Paper No. 5874 (Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Ghosh, A., A. Gulde, and H. Wolf, 2003, Exchange Rate Regimes: Choices and Consequences (Cambridge and London, MIT Press).

Ghosh, A., J. Ostry, and C. Tsangarides, 2010, “Exchange Rate Regimes and the Stability of the International Monetary System,” IMF Occasional Paper 270 (Washington DC, IMF).

Ghosh, A., J. Ostry, and M. Qureshi, 2014, “Exchange Rate Management and Crisis Susceptibility: A Reassessment,” IMF Working Paper 14/11 (Washington DC, IMF).

Guisinger, A. and D. Singer, 2010, “Exchange Rate Proclamations and Inflation-Fighting Credibility,” International Organization, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 313–37.

Levy-Yeyati, E. and F. Sturzenegger, 2001, “Exchange Rate Regimes and Economic Performance,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 47, Special Issue, pp. 62–98.

Levy-Yeyati, E. and F. Sturzenegger, 2005, “Classifying Exchange Rate Regimes: Deeds versus Words,” European Economic Review, Vol. 49, No. 6, pp. 1603–35.

Maddala, G., 1983, Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Economics (New York, Cambridge University Press).

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff, 2004, “The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements: A Reinterpretation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, No. 1, pp. 1–48.

Rogoff, K. and others 2003, “Evolution and Performance of Exchange Rate Regimes,” IMF Working Paper 03/243 (Washington DC, IMF).

Romer, D., 1993, “Openness and Inflation: Theory and Evidence,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 108, No. 4, pp. 869–903.

Shambaugh, J., 2004, “The Effects of Fixed Exchange Rates on Monetary Policy,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, No. 1, pp. 301–52.

Wolf, H., A. Ghosh, H. Berger, and A. Gulde, 2008, Currency Boards in Retrospect and Prospect (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press).

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the IMF Economic Review website (www.palgrave-journals.com/imfer)

*Atish R. Ghosh is Assistant Director, and Chief, Systemic Issues Division, in the IMF’s Research Department. Mahvash S. Qureshi and Charalambos G. Tsangarides are Senior Economists in the IMF’s Research Department. We are grateful to the editor, Pierre-Olivier Gournichas, two anonymous referees, Marcos Chamon, Charles Engel, Ayhan Kose, Jonathan D. Ostry, Eric Santor, and participants at the Canadian Economic Association Annual Conference, Ottawa, for helpful comments and suggestions. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.