Abstract

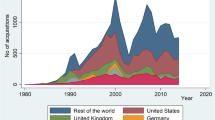

Using data on cross-border acquisitions (CBAs), this paper explores the distribution of alternative strategies pursued when multinational enterprises integrate foreign subsidiaries into their organizational structure. Based on a measure of vertical relatedness, each of the 165,000 acquisitions in our sample covering 31 source and 58 host countries can be classified as horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate. Three novel features of CBAs are highlighted. First, horizontal and vertical CBAs are relatively stable over time. Second, a considerable part of CBAs are conglomerate acquisitions whereby the financial sector is an important, though by far not the only, segment involved. Third, the wave-like growth of CBAs arises primarily from changes in conglomerate activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Data on the composition of FDI can be found in the UN World Investment Report 2015. These data show that with greenfield investment, the sectoral split (by value and for 2014) between services and manufacturing is more or less equal. For CBAs, the UN data show a slight dominance of services (around 53 percent of the total by value for 2014).

SDC Platinum data has been used elsewhere in Rossi and Volpin (2004), Di Giovanni (2005), Kessing, Konrad, and Kotsogiannis (2007), Herger, Kotsogiannis, and McCorriston (2008), Hijzen, Görg, and Manchin (2008), Coeurdacier, De Santis, and Aviat (2009), Erel, Liao, and Weisbach (2012), and Garfinkel and Hankins (2011) to study various aspects of CBAs.

As with any classification system, SIC codes offer more or less aggregate levels to delimit industries ranging from a crude definition involving broad groups such as mining, manufacturing, or services at the one-digit level to a much more detailed classification encompassing around 1,500 primary economic activities at the four-digit level. To accurately identify investment strategies pursued by MNEs, we follow Alfaro and Charlton (2009) who advocate the use of a fairly disaggregated classification at the four-digit level.

The U.S. input-output tables are updated every five years to account for industrial and technological changes. However, Fan and Goyal (2006, p. 882) find that the usage of input-output tables of different years has only a modest impact upon their results. Hence, we assume that these vertical relatedness coefficients hold over time which is consistent with the recent work of Alfaro and Chen (2012). Furthermore, using U.S. input-output tables to define the vertical relatedness for a worldwide sample of MNEs, as is also done in Acemoglu, Johnson, and Mitton (2009), raises another issue whether this accurately reflects the technological conditions around the globe. To account for this, the sensitivity analysis of the results of Section V contains a robustness check with a subsample involving only U.S. MNEs.

Within a given supply chain, vertical relatedness can arise due to commodity flows with upstream vατu and/or downstream vατd activities. Following Fan and Goyal (2006, p. 881), in our baseline scenario, no distinction will be made between these cases in the sense that the maximum value determines the coefficient of vertical relatedness, that is Vατ=max(vατu, vατd).

Another possibility to avoid the pitfalls when MNEs operate in several industries is to focus on CBA deals where both the acquirer and target firm report only one SIC code. However, this subsample includes less than 20 percent of all deals and will, hence, only be considered for our sensitivity analysis in Section V.

Considering deals between single business firms discussed in footnote 6 eliminates again the contingency of finding acquisitions meeting both criteria defining horizontal and vertical integration.

The country where an MNE is headquartered is here considered to be the ultimate source country reported in SDC. This might matter when acquisitions occur through complex ownership chains. However, in around 80 percent of the deals in our sample, the immediate and ultimate source country is identical.

CBAs involving the distribution and retailing sector are relatively rare, which manifests itself in a gap in the markers along the diagonal of Figure 3. Referring back to the observation of footnote 5 that a vertical relationship can arise with the upstream and the downstream activities, this may matter: Conventional theories of the MNE connect the motives for vertical integration with endowment-seeking. However, the (forward) integration of a distribution network might be driven by market access considerations that have more in common with motives that are usually attributed to horizontal strategies. Though such cases are empirically unimportant, a robustness check will be carried out in Section V distinguishing between cases where the vertical relationship arises only with, respectively, the upstream and downstream stages of the supply chain.

Carr, Markusen, and Maskus (2001) use the sum of the GDP between the source and host country to capture the joint market size. However, since our specification includes a source country dummy variable δ s absorbing the effect of the home market size, employing the sum of the GDP between of the source and host country yields an identical coefficient estimate.

UBS (various years) also reports an index summarizing the labor cost across all 13 surveyed professions. This WAGE INDEX will be used as robustness check when testing the nexus between labor cost and vertical CBAs in Section V.

In general, the empirical literature has related FDI to a large number of so-called institutional quality variables. However, most of these dimensions are closely correlated (Daude and Stein, 2007, p. 321ff.) and seem to measure similar effects of whether or not a country has put in place economic, legal, or political mechanisms protecting investors.

The resulting regression equation equals MtB t =2.194−0.048FRt+1(R2=0.42) where FR denotes the future stock market return. With t-values of, respectively, 11.66 and 2.71 both coefficients are significant at any conventionally used level of rejection. Estimation occurred with panel data and fixed effects for 18 countries. Extending the future stock returns to t+1 and t+2 leaves the results largely unchanged.

Specifically, the number of observations is given by the product between the total number of deals N and the set of host countries H.

A derivation of this result is made available on request.

In view of the caveats noted in Section II, we do not report the detailed results for the residual (complex) group. However, in case of considering the 5 percent value for

, the impact of GDP was insignificant while SWP gave rise to a significant coefficient. However, this result was not robust to considering different cut-off values

, the impact of GDP was insignificant while SWP gave rise to a significant coefficient. However, this result was not robust to considering different cut-off values  , which, perhaps, underscores the nonpure nature of these deals combining horizontal and/or vertical elements.

, which, perhaps, underscores the nonpure nature of these deals combining horizontal and/or vertical elements.In particular, due to the lack of heterogeneity, the variables CU and EURO drop out.

The same can also be said when contemplating the results for the manufacturing sector across all source countries in our sample.

To analyze the effect of financial variables on CBAs, Di Giovanni (2005) has looked at the impact of financial market size, measured by the capitalization of the domestic stock market relative to GDP. Crucially, his specification focuses on the degree of financial deepening in the source country emphasizing “the importance of domestic financial conditions in stimulating international investment” (p. 127). However, as discussed in Section IV, our location choice approach absorbs source country-specific variables such as the size of the domestic stock market in the fixed effect α s,t . One way to relax this would be to drop the fixed effects and introduce financial deepening as additional variable in a random effects Poisson regression. The corresponding results are consistent with the picture of Table 6. Crucially, financial deepening in the source country drives CBAs in general. However, this effect arises principally through the conglomerate part. For the sake of brevity, we do not report the detailed results, which are, however, available on request.

Instead of following Baker, Foley, and Wurgler (2008) and Erel, Liao, and Weisbach (2012) and calculate the mis-pricing regression of footnote 13 with country-level MtBs, it would in principle also be possible to construct aggregate MtBs from the firms involved in CBA deals. As emphasized in Erel, Liao, and Weisbach (2012, p. 1060ff.), the downside of this is that MtBs are available for publicly traded firms, which represent only a small part of the full sample. For our case, in around three quarters of the deals, detailed financial information is not available for both the acquirer and the target firm. Calculating nevertheless an aggregate MtB from the deals where we have the corresponding information and rerunning the regression of footnote 13 yields MtB t =4.531−0.01FRt+1 (R2=0.31) with t-values of 25.5 and 1.21, respectively. Proceeding by calculating the mis-pricing and wealth components and plugging them into the regressions of Table 6 gave rise to a positive and significant effect for MtBm (with a coefficient of around 1.5) and an insignificant effect for MtBw. Yet, the different effect across FDI strategies disappeared. Perhaps, this indicates that financial arbitrage opportunities exploited via conglomerate CBAs arise mainly via the acquisition of nonpublic (or nonlisted) firms.

References

Acemoglu, D., S. Johnson, and T. Mitton, 2009, “Determinants of Vertical Integration: Financial Development and Contracting Costs,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 63, No. 3, pp. 1251–90.

Alfaro, L. and A. Charlton, 2009, “Intra-Industry Foreign Direct Investment,” American Economic Review, Vol. 99, No. 5, pp. 2096–19.

Alfaro, L. and M. Chen, 2012, “Surviving the Global Financial Crisis: Foreign Ownership and Establishment Performance,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 4, No. 3, p. 3055.

Amihud, Y and B. Lev, 1981, “Risk Reduction as a Managerial Motive for Conglomerate Mergers,” Bell Journal of Economics, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 605–17.

Antràs, P. and S. Yeaple, 2014, “Multinational Firms and the Structure of International Trade,” in Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4, ed. by G. Gopinath, E. Helpman and K. Rogoff (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

Baker, M., C. F. Foley, and J. Wurgler, 2008, “Multinationals as Arbitrageurs: The Effect of Stock Market Valuations on Foreign Direct Investment,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 337–69.

Blonigen, B. A., R. B. Davies, and K. Head, 2003, “Estimating the Knowledge-Capital Model of the Multinational Enterprise: Comment,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 39, pp. 980–94.

Braconier, H., P. H. Norbäck, and D. Urban, 2005, “Multinational Enterprises and Wage Cost: Vertical FDI Revisited,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 446–70.

Brainard, L., 1997, “An Empirical Assessment of the Proximity-Concentration Trade-Off Between Multinational Sales and Trade,” American Economic Review, Vol. 87, No. 4, pp. 520–44.

Breinlich, H., 2008, “Trade Liberalization and Industrial Restructuring Through Mergers and Acquisitions,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 254–66.

Carr, D. L., J. R. Markusen, and K. E. Maskus, 2001, “Estimating the Knowledge Capital Model of the Multinational Enterprise,” American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 3, pp. 693–708.

Coeurdacier, N., R. A. De Santis, and A. Aviat, 2009, “Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions and European Integration,” Economic Policy, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 56–106.

Daude, C. and E. Stein, 2007, “The Quality of Institutions and Foreign Direct Investment,” Economics and Politics, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 317–44.

Di Giovanni, J., 2005, “What Drives Capital Flows? The Case of Cross-Border M&A Activity and Financial Deepening,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 127–49.

Erel, I., R. C. Liao, and M. C. Weisbach, 2012, “Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 1045–82.

Fan, J. P. H. and V. K. Goyal, 2006, “On the Patterns and Wealth Effects of Vertical Mergers’,” Journal of Business, Vol. 97, No. 2, pp. 877–902.

Fan, J. P. H. and L. H. P. Lang, 2000, “The Measurement of Relatedness: An Application to Corporate Diversification,” Journal of Business, Vol. 73, No. 4, pp. 629–60.

Froot, K. A. and J. C. Stein, 1991, “Exchange Rates and Foreign Direct Investment: An Imperfect Capital Markets Approach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 106, No. 4, pp. 1191–1217.

Garfinkel, J. A. and K. W. Hankins, 2011, “The Role of Management in Mergers and Merger Waves,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 101, No. 3, pp. 515–32.

Guimaraes, P., O. Figueirdo, and D. Woodward, 2003, “A Tractable Approach to the Firm Location Decision Problem,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 85, No. 1, pp. 201–04.

Head, K. and J. Ries, 2008, “FDI as an Outcome of the market for Corporate Control: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 74, No. 1, pp. 2–20.

Helpman, E., 1984, “A Simple Theory of Trade with Multinational Corporations,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 92, No. 3, pp. 451–71.

Herger, N., C. Kotsogiannis, and S. McCorriston, 2008, “Cross-Border Acquisitions in the Global Food Sector,” European Review of Agricultural Economics, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 563–87.

Hijzen, A., H. Görg, and M. Manchin, 2008, “Cross-Border Mergers & Acquisitions and the Role of Trade Costs,” European Economic Review, Vol. 52, No. 5, pp. 849–66.

Kessing, S., K. A. Konrad, and C. Kotsogiannis, 2007, “Foreign Direct Investment and the Dark Side of Decentralisation,” Economic Policy, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 5–70.

KPMG. various years, Corporate and Indirect Tax Rate Survey.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-De-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. W. Vishny, 1998, “Law and Finance,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 106, No. 6, pp. 1113–55.

Matsusaka, J. G., 1996, “Did Though Antitrust Enforcement Cause the Diversification of American Corporations?,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 283–94.

McGuckin, R. H., S. V. Nguyen, and S. H. Andrews, 1991, “The relationships among acquiring and acquired firms’ product lines,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 477–502.

Mueller, D., 1969, “A Theory of Conglomerate Mergers,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 83, No. 4, pp. 643–59.

Neary, J. P., 2007, “Cross-Border Mergers as Instruments of Comparative Advantage,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 74, No. 4, pp. 1229–57.

Nocke, V. and S. Yeaple, 2007, “Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions vs. Greenfield Foreign Direct Investment: The Role of Firm Heterogeneity,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 72, No. 2, pp. 336–65.

Ramondo, N., V. Rappoport, and K. J. Ruhl, 2014, “Horizontal Versus Vertical Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from U.S. Multinationals,” mimeo, UCSD, LSE, and NYU.

Rossi, S. and P. F. Volpin, 2004, “Cross-Country Determinants of Mergers and Acquisitions,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 74, No. 2, pp. 277–304.

Schmidheiny, K. and M. Brülhart, 2011, “On the Equivalence of Location Choice Models: Conditional Logit, Nested Logit and Poisson,” Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 69, No. 29, pp. 214–22.

Shleifer, A. and R. W. Vishny, 2003, “Stock Market Driven Acquisitions,” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 70, No. 3, pp. 295–311.

UBS. various years, Prices and Earnings—A Comparison of Purchasing Power Around the Globe (Zurich: UBS).

Wei, S. -J., 2000, “How Taxing is Corruption on International Investors?,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 82, No. 1, pp. 1–11.

Williamson, O., 1981, “The Modern Corporation: Origins, Evolution, Attributes,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 1537–68.

Williamson, O., 1970, Corporate Control and Business Behavior: An Inquiry into the Effects of Organizational Form on Enterprise Behavior (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall).

Yeaple, S. R., 2003, “The Complex Integration Strategies of Multinationals and Cross Country Dependencies in the Structure of Foreign Direct Investment,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 293–314.

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the IMF Economic Review website (www.palgrave-journals.com/imfer)

*Nils Herger is program manager of the Central Bankers’ Courses at the Study Center Gerzensee and lecturer in economics at the University of Bern. Steve McCorriston is professor of agricultural economics at the University of Exeter. The authors would like to thank Ron Davies, the conference participants at the ETSG 2012 in Leuven, the seminar participants at the University Collage of Dublin, and two anonymous referees for valuable discussions and comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41308-017-0034-4.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendices

Appendix I

Country coverage

The common sample covers the following countries. Wage data of UBS (various years) refer to the cities in parentheses:

As Source

Australia (Sydney), Austria (Vienna), Belgium (Brussels), Brazil (Sao Paulo), Canada (Toronto), China (Shanghai), Czech Republic (Prague), Denmark (Copenhagen), Finland (Helsinki), France (Paris), Germany (Frankfurt), Greece (Athens), Hong Kong (Hong Kong), Hungary (Budapest), Indonesia (Djakarta), Ireland (Dublin), Italy (Milan), Japan (Tokyo), Mexico (Mexico City), the Netherlands (Amsterdam), Norway (Oslo), Poland (Warsaw), Portugal (Lisbon), Russia (Moscow), Singapore (Singapore), South Africa (Johannesburg), Spain (Madrid), Sweden (Stockholm), Switzerland (Zurich), the United Kingdom (London), and the United States (Washington).

As host

Argentina (Buenos Aires), Australia (Sydney), Austria (Vienna), Bahrain (Manama), Belgium (Brussels), Brazil (Sao Paulo), Bulgaria (Sofia), Canada (Toronto), Chile (Santiago de Chile), China (Shanghai), Colombia (Bogota), Czech Republic (Prague), Cyprus (Nikosia), Denmark (Copenhagen), Estonia (Tallinn), Finland (Helsinki), France (Paris), Germany (Frankfurt), Greece (Athens), Hong Kong (Hong Kong), Hungary (Budapest), India (Mumbai), Indonesia (Djakarta), Ireland (Dublin), Israel (Tel Aviv), Italy (Milan), Japan (Tokyo), Kenya (Nairobi), Korea (Seoul), Latvia (Riga), Lithuania (Vilnius), Luxembourg (Luxembourg), Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur), Mexico (Mexico City), the Netherlands (Amsterdam), New Zealand (Auckland), Norway (Oslo), Panama (Panama), Peru (Lima), Philippines (Manila), Poland (Warsaw), Portugal (Lisbon), Romania (Bucharest), Russia (Moscow), Singapore (Singapore), Slovak Republic (Bratislava), Slovenia (Ljubljana), South Africa (Johannesburg), Spain (Madrid), Sweden (Stockholm), Switzerland (Zurich), Thailand (Bangkok), Turkey (Istanbul), Ukraine (Kiev), United Arab Emirates (Dubai), the United Kingdom (London), the United States (Washington), and Venezuela (Caracas).

Appendix II

A reviewer’s appendix is available online.

, the impact of GDP was insignificant while SWP gave rise to a significant coefficient. However, this result was not robust to considering different cut-off values

, the impact of GDP was insignificant while SWP gave rise to a significant coefficient. However, this result was not robust to considering different cut-off values  , which, perhaps, underscores the nonpure nature of these deals combining horizontal and/or vertical elements.

, which, perhaps, underscores the nonpure nature of these deals combining horizontal and/or vertical elements.