Abstract

This paper uses a 42-country model of production and trade to assess the implications of eliminating current account imbalances for relative wages, relative GDPs, real wages, and real absorption. How much relative GDPs need to change depends on flexibility of two forms: factor mobility and adjustment in sourcing of imports, with more flexibility requiring less change. At the extreme, U.S. GDP falls by 30 percent relative to the world's. Because of the pervasiveness of nontraded goods, however, most domestic prices move in parallel with relative GDP, so that changes in real GDP are small.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We describe how we created this sample and where our data come from in Section II.

This number is not only very large absolutely, it is also large relative to U.S. GDP. Australia, Greece, and Portugal have larger deficit-to-GDP ratios. Some small countries run current account surpluses that are much larger fractions of their GDP. The Bureau of Economics Analysis reports the U.S. current account deficit in 2006 as $857 billion, 6.1 percent of GDP.

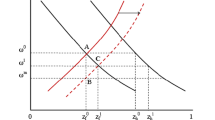

While our framework can quite handily deal with a multitude of countries, its analytic essence derives from the two-country model of trade and unilateral transfers of Dornbusch, Fischer, and Samuelson (1977).

Corsetti, Martin, and Pesenti (2007) develop a symmetric two-country model in which adjustment can also occur across both the intensive and extensive margins. They examine the long-run consequences of the effects of improving net export deficits of 6.5 percent of GDP in one country to a balanced position. In the version of the model in which all adjustment takes place at the intensive margin, the authors find that closing the external imbalance requires a fall in long-run consumption (of the country undergoing the adjustment) by around 6 percent and a depreciation of the real exchange rate and the terms of trade by 17 and 22 percent respectively. When adjustment can also occur at the extensive margin, there is a much smaller depreciation in the real exchange rate and in the terms of trade, of 1.1 percent and 6.4, respectively. The changes in consumption and welfare under the two versions of the model, however, are similar.

To generalize our analysis to incorporate multiple factors of production one may think of L i as a vector of factors.

See Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz (2008) to see how the model could be respecified in terms of monopolistic competition with heterogeneous firms, as in Melitz (2003) and Chaney (forthcoming).

More precisely, the parameter α i captures both manufactures used in final absorption and manufactures used as intermediates in the production of nonmanufactures. For simplicity, we ignore this feedback from the manufacturing sector to the nonmanufacturing sector. As we discuss below, this feedback appears to be small.

If the unit cost function in nonmanufactures is w i N/a i , reflecting productivity a i , then

We have to confront the problem that the data imply nonzero current account and trade balances for the world as a whole. Our procedures cannot explain this discrepancy so we allocated the deficits to countries in proportion to their GDPs. Because we use only importer data to measure bilateral trade in manufactures, world trade in manufactures balances automatically.

For each country i other than ROW a measure of β is available in some year in the interval 1991–2003. Our measure of β for ROW is the simple average of the βs across countries not in ROW.

As mentioned earlier, we do not take account of the use of manufactures as intermediates in the production of nonmanufactures. According to the 1997 input-output use table for the United States, the share of intermediates in the gross production of nonmanufactures is 8.5 percent.

In the text, we refer to a percentage change in x as 100(x̂−1) and the percentage change in x 2 relative to x 1 as 100[(◯ 2/◯ 1)−1].

References

Alvarez, Fernando, and Robert E. Lucas, 2007, “General Equilibrium Analysis of the Eaton-Kortum Model of International Trade,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 54, No. 6, pp. 726–768.

Bernard, Andrew B., Jonathan Eaton, J. Bradford Jensen, and Samuel Kortum, 2003, “Plants and Productivity in International Trade,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 1268–1290.

Chaney, Thomas, forthcoming, “Distorted Gravity: Heterogeneous Firms, Market Structure, and the Geography of International Trade,” American Economic Review.

Corsetti, Giancarlo, Philippe Martin, and Paolo Pesenti, 2007, “Varieties and the Transfer Problem: The Extensive Margin of Current Account Adjustment” (unpublished; Federal Reserve Bank of New York).

Dekle, Robert, Jonathan Eaton, and Samuel Kortum, 2007, “Unbalanced Trade,” American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 97, No. 3, pp. 351–355.

Dornbusch, Rudiger, Stanley Fisher, and Paul Samuelson, 1977, “Comparative Advantage, Trade, and Payments in a Ricardian Model with a Continuum of Goods,” American Economic Review, Vol. 67, No. 4, pp. 823–829.

Eaton, Jonathan, and Samuel Kortum, 2002, “Technology, Geography, and Trade,” Econometrica, Vol. 70, No. 5, pp. 1741–1780.

Eaton, Jonathan, Samuel Kortum, and Francis Kramarz, 2008, “An Anatomy of International Trade: Evidence from French Firms” (unpublished; CREST-INSEE, New York University, University of Chicago).

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2006, International Financial Statistics Yearbook (Washington, IMF).

Melitz, Marc, 2003, “The Impact of Trade on Aggregate Industry Productivity and Intra-Industry Reallocations,” Econometrica, Vol. 71, No. 6, pp. 1625–1695.

Obstfeld, Maurice, and Kenneth Rogoff, 2005, “Global Current Account Imbalances and Exchange Rate Adjustments,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 67–146.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2007, “Structural Analysis Database,” Available on the Internet: www.oecd.org/document/15/0,2340,en_2649_201185_1895503_1_1_1_1,00.html.

Ruhl, Kim, 2005, “The Elasticity Puzzle in International Economics” (unpublished; University of Texas at Austin).

United Nations Industrial Development Organization, 2006 Industrial Statistics Database Available on the Internet: www.unido.org/index.php.

United Nations Statistics Division, 2006 United Nations Commodity Trade Database Available on the Internet: http://comtrade.un.org/.

United Nations Statistical Division, 2007 National Accounts Available on the Internet: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama.

Additional information

*Robert Dekle is professor of economics at the University of Southern California; Jonathan Eaton is professor of economics at New York University; and Samuel Kortum is professor of economics at the University of Chicago. The authors have benefitted from comments by our discussant, Doireann Fitzgerald. Eaton and Kortum gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation.