Abstract

This paper describes a newly constructed panel data set containing measures of de jure restrictions on cross-border financial transactions for 91 countries from 1995 to 2005. The new data set adds value to existing capital control indices by providing information at a more disaggregated level. This structure allows for the construction of various subindices, including those for individual asset categories, for inflows vs. outflows, and for residents vs. nonresidents. Disaggregations of this kind open up new ways to address questions of interest in the field of international finance. Some potential research avenues are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Even so, however, no clear consensus has emerged on the effects of financial cross-border flows on economic growth and other outcome variables, unlike, for example, the literature on the cross-border trade of goods and services. For recent reviews of the state of the financial globalization literature, see, for example, Kose and others (2006) and Dell'Ariccia and others (2008).

Taking a disaggregated approach appears to be promising. As Henry (2007) notes, existing evidence suggests that opening equity markets to foreign investors may avoid some of the problems associated with the liberalization of debt flows, and so “[a]t a minimum, the distinction between debt and equity is critical” (p. 889). The data set documented here allows researchers to investigate such differences.

Not all categories reported in the AREAER are coded here, given their limited importance in the composition of de facto flows and resource constraints in the data collection process. These categories include derivatives and other instruments, credit operations (except for the subcategory financial credits, see main text), real estate transactions, and personal capital transactions.

The labels in square brackets correspond to the variable names used in the published data set.

Restrictions on bond transactions were not recorded in the AREAER in 1995 and 1996.

For example, in 1999, Bulgarian residents' purchases abroad of capital market securities (shares and bonds) only required “[p]rior registration with the BNB” (IMF, 2000, p. 150) and were therefore coded as 0 (unrestricted).

For example, in 2005, in the United States local purchases by nonresidents of shares or other securities of a participating nature were free from restrictions except for investments “in the nuclear energy, maritime, communications, air and land transport, and shipping industries” (IMF, 2006, p. 1258); transactions were also prohibited with “Cuba and Cuban nationals; the Islamic Republic of Iran; Myanmar; Sudan” (IMF, 2006, p. 1259). These transactions were coded as 0 (unrestricted).

The definition of residence in the Balance of Payments Manual is based on the “transactor's center of economic interest” (IMF, 1993, p. 20) and may therefore differ from other definitions based on nationality or (other) legal criteria, such as tax laws.

The interpretation of directionality is a complex issue—see below for a more detailed discussion.

This view follows the Balance of Payments Manual, which notes that “[d]irect investment is classified primarily on a directional basis—resident direct investment abroad and nonresident investment in the reporting economy” (IMF, 1993, p. 81). Thus, unlike the other categories, direct investment inflows and outflows can be equated with nonresident and resident transactions, respectively. For symmetry, the analogous approach is taken for the collective investment and financial credit categories.

Matching these inflow/outflow aggregates with their de facto counterparts is nontrivial: capital flows data are typically reported as the net changes in external assets (outflows) and liabilities (inflows), which mixes different types of transactions. For example, a reduction in liabilities due to nonresidents selling domestic bonds is effectively counted as a negative inflow, while it would be considered a (positive) outflow in the de jure aggregation discussed here. Transforming the de facto data by defining Outflows=max(ΔAssets,0)−min(ΔLiabilities,0) and Inflows=−min(ΔAssets,0)+max(ΔLiabilities,0) is a possible solution.

This is only one aspect of intensity. A broader intensity measure would reflect the different types of restrictions (such as approval vs. taxation vs. prohibition) as well as the degree to which de jure restrictions are actually enforced in practice. Quinn (1997) attempts to tackle the former aspect, described in more detail in the next section.

Johnston and Tamirisa (1998) analyze in more detail the various subcomponents of Tamirisa's (1999) index.

This is not to say, however, that these other three variables have no bearing on capital account restrictiveness; for example, multiple exchange rate practices may make capital account transactions more costly even in the absence of other, more direct restrictions on capital account transactions.

Such a ranking is difficult as the relative importance of restrictions likely depends on the specific context. For example, whether “approval required but frequently granted” is equally restrictive as “approval not required, but heavily taxed” (as assumed in Quinn, 1997) will depend on the level of the tax rate and the precise definition of “frequently granted.”

A possible exception is Brune (2006) who, as described in Brune and Guisinger (2007), constructed a data set covering 187 countries during 1965–2004 and containing separate information on inflow and outflow restrictions in 5 categories. She reports high correlations with the IMF dummy and the indices by Tamirisa (1999), Miniane (2004), and Quinn (1997); however, Brune's data set has not been available to the author.

The correlation with the binary equity liberalization index by Bekaert, Harvey, and Lundblad (2005) (switching from 1 to 0 when equity markets are liberalized) is statistically insignificant as their data set reports only six liberalization episodes for the sample of the new index: Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, and Tunisia in 1995, South Africa in 1996, and Oman and Saudi Arabia in 1999.

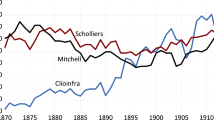

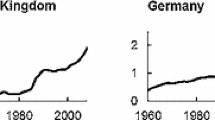

The 2005 reversal is also reflected in individual asset categories except for foreign direct investment where the trend toward fewer restrictions continues even into 2005; inflow restrictions on average also continued to decrease (Figure 3).

The capital controls index for the United States, for example, is coded as nonzero in the new index because of restrictions on foreign mutual funds (“sale or issue locally by nonresidents”) under the Investment Company Act (see IMF, 1996).

References

Bekaert, Geert, Campbell R. Harvey, and Christian Lundblad, 2005, “Does Financial Liberalization Spur Growth?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp. 3–55.

Brune, Nancy, 2006, “Financial Liberalization and Governance in the Developing World,” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation; New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University).

Brune, Nancy, and Alexandra Guisinger, 2007, “Myth or Reality? The Diffusion of Financial Liberalization in Developing Countries,” Yale University MacMillan Center Working Paper (New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University).

Chinn, Menzie D., and Hiro Ito, 2008, “A New Measure of Financial Openness,” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 309–322.

Dell'Ariccia, Giovanni, Julian di Giovanni, André Faria, Ayhan Kose, Paolo Mauro, Jonathan Ostry, Martin Schindler, and Marco Terrones, 2008, Reaping the Benefits of Financial Globalization, IMF Occasional Paper No. 264 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Edison, Hali, and Frank Warnock, 2003, “A Simple Measure of the Intensity of Capital Controls,” Journal of Empirical Finance, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 81–103.

Henry, Peter Blair, 2007, “Capital Account Liberalization: Theory, Evidence, and Speculation,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 887–935.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 1993, Balance of Payments Manual (Washington, International Monetary Fund, 5th ed.).

International Monetary Fund(IMF), various years, Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Johnston, R. Barry, and Natalia T. Tamirisa, 1998, “Why Do Countries Use Capital Controls?” IMF Working Paper 98/181 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Kose, Ayhan, Eswar Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2006, “Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal,” IMF Working Paper 06/189 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Lane, Philip R., and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2007, “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 223–250.

Miniane, Jacques, 2004, “A New Set of Measures on Capital Account Restrictions,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 276–308.

Mody, Ashoka, and Antu Panini Murshid, 2005, “Growing Up With Capital Flows,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 249–266.

Prati, Alessandro, Martin Schindler, and Patricio Valenzuela, 2008, “Who Benefits from Capital Account Liberalization? Evidence from Firm-Level Credit Ratings Data” (unpublished; Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Quinn, Dennis P., 1997, “The Correlates of Change in International Financial Regulation,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 91 (September), pp. 531–551.

Tamirisa, Natalia T., 1999, “Exchange and Capital Controls as Barriers to Trade,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 69–88.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on IMF Staff Papers website (http://www.palgrave.com/imfsp).

*Martin Schindler is an economist in the Research Department of the IMF. The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions by Lore Aguilar during the initial stages of this project. An early version of the data was used in Dell'Ariccia and others (2008)—all collaborators on that project also contributed in some form to the data effort presented here. The author also benefited from discussions with Enrica Detragiache, Peter Blair Henry, Ayhan Kose, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, Jacques Miniane, Eswar Prasad, Dennis Quinn, and Frank Warnock. Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti and Dennis Quinn kindly provided their updated data sets. Patricio Valenzuela and Ermal Hitaj provided outstanding research assistance. The data set described in this paper can be downloaded from the IMF Staff Papers website.