Abstract

The paper examines the link between net capital flows and international reserves emphasizing the external financing of reserve accumulation in the context of increasing international financial integration. The paper finds that the effect of net capital flows on reserve accumulation has shifted from negative to positive for emerging markets but not for advanced countries. The empirical results suggest that in recent years emerging markets, with concerns about sudden stops in capital flows, have rapidly built up reserves through external financing with net capital inflows, whereas the advanced countries, with more secure access to international finance, have balanced reserves accumulation with investments in higher-yielding foreign assets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Before the 1990s, emerging market reserves fluctuated between 3 and 4 months of imports. At the end of 2005, they stood at an average of 5.8 months of imports. Even in terms of the Guidotti – Greenspan rule that countries hold reserves to cover short-term external debt (Rodrik, 2006), emerging market reserve cover has been very high: for example, the ratio was greater than 3.0 for Korea and 6.5 for China in 2005. However, recent research suggests that a broader metric should be used for assessing reserve adequacy (see Lipschitz, Messmacher, and Mourmouras, 2006).

Aizenman and Marion (2004) note that the opportunity cost variable may not be properly measured because the composition of reserves is not adequately reflected, and until the early 1990s, most emerging markets did not have market-determined domestic interest rates.

Such a reserve volatility measure, however, can be contaminated because it combines jumps in reserves owing to reserve restocking and sudden declines with speculative attacks (Flood and Marion, 2002).

The traditional buffer stock model assumes that the liquidation cost of assets for restocking reserves is known and Bar-Ilan, Marion, and Perry (2007) suggest that reserve adjustment costs are important in explaining the time path of reserve accumulation.

As creditors in sovereign debt markets have limited enforcement rights (for example, few possibilities for seizing country assets), political and credit risks play an important role in capital flows (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2004b).

Our index corresponds to the Reinhart-Rogoff classification as follows: index value 1 has categories from “no separate legal tender” to “de facto peg,” index value 2 has categories from “pre-announced crawling peg” to “managed floating,” and index value 3 has categories from “freely floating” to “freely falling.” We exclude sample observations for the category: “dual market in which parallel market data is missing.”

Aizenman and Marion (2004) find the volatility of export receipts to be statistically insignificant. We exclude this variable from our regressions because the sign of its coefficient varies depending on which other variables are included in the model and is highly sensitive to normalizations.

To account for endogeneity (high reserve holdings may reduce exchange rate variability), we also used the lagged values of exchange rate regime dummies as instruments. The results were qualitatively the same.

We ensure that the instruments are uncorrelated with the model error as follows: (i) an instrument is regressed on the endogenous regressor and country dummies to derive the component of the instrument that is uncorrelated with the regressor; (ii) the dependent variable is regressed on a set of exogenous variables including country dummies to derive the component of the dependent variable that contains the model error; and (iii) regress the filtered dependent variable from (ii) on the filtered instrument from (i), and test if the filtered instrument is statistically insignificant using a robust covariance matrix. Also, the Stock and Yogo (2005) test supports the validity of our instruments: the test rejected the null hypothesis of weak instruments at the 1 percent level for any three endogenous variables.

To account for the financial dimension of international transactions, we also use the M2-GDP ratio in place of the population variable. Like the population variable, the M2-GDP ratio has a statistically significant positive effect only for emerging markets. This result suggests that the level of monetization is not a determinant of reserve holdings for advanced economics, which already have relatively well developed financial markets.

Since the data on sovereign ratings are often not available for emerging markets in the 1980s, we also estimated regressions for the 1990–2005 period. The results were very similar to those reported in this paper.

To account for the cost of acquiring international currencies for building up reserves, we also used the EMBI and EMBI plus spreads for Latin American and non-Latin American countries for 1992–2005 as a proxy for the opportunity cost in emerging markets—the IV estimate was negative but not statistically significant.

The average total effect of net capital flows during a period can be measured by β CF +β GL *GLOBAVE, where AVE denotes the period average value. In particular, for 2001–05, the total effect based on the IV estimator in panel B is 0.127 (=−1.338+0.436 × 3.36) and −0.506 (=1.448−0.398 × 4.91) for emerging markets and advanced economics, respectively. However, its effect at very low levels of financial integration as in the 1980s can be positive for advanced economics, compared to a negative effect during the 1980s in Table 1. Thus, for advanced economics, the effect of net capital flows on reserves is mixed in the early stages of financial integration.

References

Aizenman, Joshua, and Jaewoo Lee, 2007, “International Reserves: Precautionary Versus Mercantilist Views, Theory and Evidence,” Open Economies Review, Vol. 18, pp. 191–214.

Aizenman, Joshua, and Nancy Marion, 2003, “The High Demand for International Reserves in the Far East: What Is Going On?” Japanese and International Economies, Vol. 17, pp. 370–400.

Aizenman, Joshua, and Nancy Marion, 2004, “International Reserve Holdings with Sovereign Risk and Costly Tax Collection,” Economic Journal, Vol. 114, pp. 569–591.

Almeida, Heitor, Murillo Campello, and Michael S. Weisbach, 2004, “The Cash Flow Sensitivity of Cash,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 59, pp. 1777–1804.

Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond, 1991, “Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 58, pp. 277–297.

Bar-Ilan, Avner, Nancy Marion, and David Perry, 2007, “Drift Control of International Reserves,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 31, pp. 3110–3137.

Ben-Bassat, Avraham, and Daniel Gottlieb, 1992, “Optimal International Reserves and Sovereign Risk,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 33, pp. 345–362.

Caballero, Ricardo J., and Stavros Panageas, 2005, “A Quantitative Model of Sudden Stops and External Liquidity Management,” NBER Working Paper No. 11293 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Calvo, Guillermo A., 1998, “Capital Flows and Capital-Market Crises: The Simple Economics of Sudden Stops,” Journal of Applied Economics, Vol. 1, pp. 35–54.

Cantor, Richard, and Frank Packer, 1996, “Determinants and Impact of Sovereign Credit Ratings,” FRBNY Economic Policy Review, Vol. 2 (Federal Reserve Bank of New York, October), pp. 37–53.

Choi, Woon Gyu, and David Cook, 2004, “Liability Dollarization and the Bank Balance Sheet Channel,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 64, pp. 247–275.

Choi, Woon Gyu, Sunil Sharma, and Maria Strömqvist, 2007, “Capital Flows, Financial Integration, and International Reserve Holdings: The Recent Experience of Emerging Markets and Advanced Economies,” IMF Working Paper 07/151 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Devereux, Michael, and Alan Sutherland, 2007, “A Portfolio Model of Capital Flows to Emerging Markets,” paper prepared for the Conference on New Perspectives on Financial Globalization held at the International Monetary Fund, Washington, April.

Dooley, Michael P., David Folkerts-Landau, and Peter Garber, 2004, “The Revived Bretton Woods System: The Effects of Periphery Intervention and Reserve Management on Interest Rates and Exchange Rates in Center Countries,” NBER Working Paper 10332 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Durdu, Bora, Enrique Mendoza, and Marco Terrones, forthcoming, “Precautionary Demand for Foreign Assets in Sudden Stop Economies: An Assessment of the New Mercantilism,” Journal of Development Economics.

Edwards, Sebastian, 1984, “The Demand for International Reserves and Monetary Equilibrium: Some Evidence from LDCs,” Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 66, pp. 495–500.

Edwards, Sebastian, 1985, “On the Interest-Rate Elasticity of the Demand for International Reserves: Some Evidence from Developing Countries,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 4, pp. 287–295.

Edwards, Sebastian, 2004, “Thirty Years of Current Account Imbalances, Current Account Reversals and Sudden Stops,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 51 (Special Issue), pp. 1–49.

Flood, Robert, and Nancy Marion, 2002, “Holding International Reserves in an Era of High Capital Mobility,” IMF Working Paper 02/62 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Flood, Robert, and Olivier Jeanne, 2005, “An Interest Rate Defense of a Fixed Exchange Rate?” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 66, pp. 471–484.

Frankel, Jeffrey A., 2005, “Mundell-Fleming Lecture: Contractionary Currency Crashes in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 149–192.

Frankel, Jeffrey A.,and Rudiger Dornbusch, 1995, “The Flexible Exchange Rate System: Experience and Alternatives,” in On Exchange Rates, ed. by Jeffrey A. Frankel (Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press).

Frenkel, Jacob A., and Boyan Jovanovic, 1981, “Optimal International Reserves: A Stochastic Framework,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 91, pp. 507–514.

Heller, Robert H., and Mohsin S. Khan, 1978, “The Demand for International Reserves under Fixed and Floating Exchange Rates,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 623–649.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2003, “Three Current Policy Issues in Developing Countries,” World Economic Outlook, (Washington, International Monetary Fund, September).

Jeanne, Olivier, 2007, “International Reserves in Emerging Market Countries: Too Much of a Good Thing?” Brookings Papers in Economic Activity, Vol. 1, pp. 1–55.

Kaminsky, Graciela, and Carmen M. Reinhart, 2000, “On Crises, Contagion, and Confusion,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 51, pp. 145–168.

Kim, Chang-Soo, David Mauer, and Ann Sherman, 1998, “The Determinants of Corporate Liquidity: Theory and Evidence,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 33, pp. 335–359.

Lane, Philip R., and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2006, “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities, 1970–2004,” IMF Working Paper 06/69 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Lipschitz, Leslie, Miguel Messmacher, and Alexandros Mourmouras, 2006, “Reserve Adequacy: Much Higher than You Thought?” (unpublished; Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Lucas, Robert, 1990, “Why Doesn't Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries?” American Economic Review, Vol. 80, pp. 92–96.

Mellios, Constantin, and Eric Paget-Blanc, 2006, “Which Factors Determine Sovereign Credit Ratings?” European Journal of Finance, Vol. 12, pp. 361–377.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff, 2004a, “The Modern History of Exchange Rate Arrangements: A Reinterpretation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119, pp. 1–48.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff, 2004b, “Serial Default and the ‘Paradox’ of Rich-to-Poor Capital Flows,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, pp. 53–58.

Rodrik, Dani, 2006, “The Social Cost of Foreign Exchange Reserves,” NBER Working Paper No. 11952 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research).

Stock, James H., and Motohiro Yogo, 2005, “Testing for Weak Instruments in Linear IV Regression,” in Identification and Inference for Econometric Models, Essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg (Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University Press), pp. 80–108.

Van Wijnbergen, Sweder, 1990, “Cash/Debt Buy-Backs and the Insurance Value of Reserves,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 29, pp. 123–131.

Additional information

*Woon Gyu Choi is a senior economist at the IMF Institute; Sunil Sharma is the director of the IMF–Singapore Regional Training Institute; and Maria Strömqvist, a doctoral student at the Stockholm School of Economics, was a summer intern at the IMF Institute in 2005. The authors thank David Cook, Enrica Detragiache, Michael Devereux, Robert Flood, Brenda Gonzalez-Hermosillo, Leslie Lipschitz, Enrique Mendoza, Jaihyun Nahm, Jorge Roldos, Kwanho Shin, Evan Tanner, and an anonymous referee for helpful comments. The authors are also grateful to participants at the conference on “Korea and the World Economy” held in Seoul in 2006, and to the IMF Institute's weekly seminar for discussions. Si-Yeon Lee provided valuable research assistance in an earlier stage of the project, and Anastasia Guscina assisted in the collection of data.

Appendices

Appendix I. Country Group List

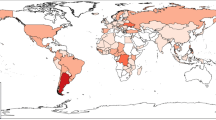

The emerging market country group (36) comprises Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan Province of China, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The advanced country group (24) comprises Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong SAR, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States. Our country groups correspond to the groups “emerging market countries” and “industrial countries” in the IMF Research Department's Global Data Source. Our emerging market group is similar to the “emerging market countries” except that it includes Croatia, Egypt, Jordan, Kazakhstan, and Uruguay and excludes Hong Kong SAR and Singapore. Our advanced country group includes Hong Kong SAR and Singapore because their per capita incomes have been well above the sample mean of the advanced economies for at least the last 10 years. Also, their financial integration measures have been among the highest over the period considered.

Appendix II. Descriptive Statistics

See Table A1 for descriptive statistics of key variables.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, W., Sharma, S. & Strömqvist, M. Net Capital Flows, Financial Integration, and International Reserve Holdings: The Recent Experience of Emerging Markets and Advanced Economies. IMF Econ Rev 56, 516–540 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.35

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.35