Abstract

This paper explores international bond spillovers using daily and weekly data on yields on inflation-indexed bonds and associated inflation expectations for the United States, Australia, Canada, France, Sweden, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The analysis starts in 2002, by which point U.S. inflation-indexed markets had matured. Real bond yields are found to be closely linked across countries, with developments in U.S. markets determining around half of real foreign yields and no evidence of spillovers back to the United States. Spillovers in inflation expectations are smaller and the direction of causation is less clear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Sack and Elsasser (2004) for an overview of the U.S. inflation-indexed market.

Jorion (1996) and Breedon, Henry, and Williams (1999), who examine longer maturities, find no evidence of real interest parity across the major industrial countries. Chinn and Frankel (1995) find little evidence of real interest parity for shorter maturities. Gagnon and Unferth (1995); Goodwin and Grennes (1994); and Awad and Goodwin (1998) do find some support for real interest parity for short-term interest rates. See Ferreira and León-Ledesma (2007) for recent evidence on real interest parity for both developed and emerging economies, and for additional references.

The yield on an inflation-indexed bond would also include a premium to compensate investors for its lower liquidity relative to a conventional bond. See Sack (2002) and Shen (2006) for estimates of the size of this liquidity premium.

Sweden issued its first inflation-indexed bond in March 1994.

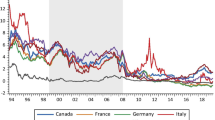

Germany first issued an inflation-indexed bond in 2006. The yields are also highly correlated with French yields.

The only significant deviation is in the case of Canada, for which the first inflation-linked bond matures in 2021 and is used throughout the sample.

Analysis using earlier start dates—1998 and mid-2000—find very similar results except that, as expected, there is more evidence of inefficiencies in the U.S. inflation-indexed market (and in derived inflation expectations).

Correlations since mid-2000 do not show this anomaly.

This is true irrespective of the links across markets. For example, bond yields could be cointegrated if they react to information in a similar manner. Even so, past bond yields should not matter for current movements.

Note that there is a small expected change in the return due to the shift in the duration of the bond from t to t + 1, but with a 10-year bond, a change of one day makes no noticeable difference.

U.S. bonds are unique in that they are traded more or less continually 24 hours a day, and (in contrast to the other countries in the sample) the fix in our data set varies slightly depending on the day, varying from 3 to 7.30 pm EST.

Note that, since interest rates are a random walk, the presence of cointegration would not influence these results. In any case, standard tests show little evidence of cointegration.

We also ran rUS, p*, r*, pUS for all countries but the results were quite similar to rUS, r*, p*, pUS.

These results are consistent with Chinn and Frankel (2005) and Cumby and Mishkin (1986).

References

Almeida, A., C. Goodhart, and R. Payne, 1998, “The Effects of Macroeconomic News on High Frequency Exchange Rate Behavior,” The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 383–408.

Andersen, T., T. Bollerslev, F. Diebold, and C. Vega, 2003, “Micro Effects of Macro Announcements: Real-Time Price Discovery in Foreign Exchange,” American Economic Review, Vol. 93, No. 1, pp. 38–62.

Andersen, T., T. Bollerslev, F. Diebold, and C. Vega, 2007, “Real-Time Price Discovery in Stock, Bond and Foreign Exchange Markets,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 251–277.

Awad, M., and B. Goodwin, 1998, “Dynamic Linkages Among Real Interest Rates in International Capital Markets,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 17 (December), pp. 881–907.

Bayoumi, T., and A. Swiston, 2007, “The Ties that Bind: Measuring International Spillovers Using Inflation-Indexed Bond Yields,” IMF Working Paper 07/128 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Becker, K., J. Finnerty, and M. Gupta, 1990, “The Intertemporal Relation Between the U.S. and Japanese Stock Markets,” The Journal of Finance, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 1297–1306.

Becker, K., J. Finnerty, and J. Friedman, 1995, “Economic News and Equity Market Linkages Between the U.S. and U.K,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 19 (October), pp. 1191–1210.

Breedon, F., B. Henry, and G. Williams, 1999, “Long-Term Real Interest Rates: Evidence on the Global Capital Market,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 128–142.

Bremnes, H., O. Gjerde, and F. Soettem, 2001, “Linkages Among Interest Rates in the United States, Germany and Norway,” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 103, No. 1, pp. 127–145.

Chinn, M., and J. Frankel, 1995, “Who Drives Real Interest Rates Around the Pacific Rim: the USA or Japan?” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 14, No. 6, pp. 801–821.

Chinn, M., and J. Frankel, 2005, “The Euro Area and World Interest Rates” (unpublished; University of Wisconsin). Available via the Internet: www.ssc.wisc.edu/~mchinn/research.html.

Christie-David, R., M. Chaudhry, and W. Khan, 2002, “News Releases, Market Integration, and Market Leadership,” The Journal of Financial Research, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 223–245.

Cumby, R., and F. Mishkin, 1986, “The International Linkage of Real Interest Rates: The European–US Connection,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 23–25.

Diebold, F., and K. Yilmaz, 2009, “Measuring Financial Asset Return and Volatility Spillovers, with Application to Global Equity Markets,” Economic Journal, Vol. 119, (January), pp. 158–71.

Ehrmann, M., and M. Fratzscher, 2003, “Monetary Policy Announcements and Money Markets: A Transatlantic Perspective,” International Finance, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 309–328.

Ehrmann, M., and M. Fratzscher, 2005, “Equal Size, Equal Role? Interest Rate Interdependence Between the Euro Area and the United States,” Economic Journal, Vol. 115 (October), pp. 928–948.

Ehrmann, M., M. Fratzscher, and R. Rigobon, 2007, “Stocks, Bonds, Money Markets and Exchange Rates: Measuring International Financial Transmission,” NBER Working Paper 11166 (Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Fair, R., 2003, “Shock Effects on Stocks, Bonds, and Exchange Rates,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 22 (June), pp. 307–341.

Fatum, R., and B. Scholnick, 2006, “Do Exchange Rates Respond to Day-to-Day Changes in Monetary Policy Expectations When No Policy Changes Occur?” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 1641–57.

Faust, J., J. Rogers, S. Wang, and J. Wright, 2007, “The High-Frequency Response of Interest Rates to Macroeconomic Announcements,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 54 (May), pp. 1051–1068.

Ferreira, A., and M. León-Ledesma, 2007, “Does the Real Interest Parity Hypothesis Hold? Evidence for Developed and Emerging Markets,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 26 (April), pp. 364–382.

Gagnon, J., and M. Unferth, 1995, “Is There a World Real Interest Rate?” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 14 (December), pp. 845–855.

Goldberg, L., and D. Leonard, 2003, “What Moves Sovereign Bond Markets? The Effects of Economic News on U.S. and German Yields, Federal Reserve Bank of New York,” Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Vol. 9, No. 9, pp. 1–7.

Goodwin, B., and T. Grennes, 1994, “Real Interest Rate Equalization and the Integration of International Financial Markets,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 107–124.

Gravelle, T., and R. Moessner, 2001, “Reactions of Canadian Interest Rates to Macroeconomic Announcements: Implications for Monetary Policy Transparency,” Bank of Canada Working Paper 2001-5.

Jorion, P., 1996, “Does Real Interest Parity Hold at Longer Maturities? Journal of International Economics, Vol. 40 (February), pp. 105–126.

Kim, S., and J. Sheen, 2000, “International Linkages and Macroeconomic News Effects on Interest Rate Volatility—Australia and the US,” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 85–113.

Lin, W., R. Engle, and T. Ito, 1994, “Do Bulls and Bears Move Across Borders? International Transmission of Stock Returns and Volatility,” The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 507–538.

Sack, B., 2002, “Deriving Inflation Expectations from Nominal and Inflation-Indexed Yields,” Journal of Fixed Income, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 1–12.

Sack, B., and R. Elsasser, 2004, “Treasury Inflation-Indexed Debt: A Review of the U.S. Experience, Federal Reserve Bank of New York,” Economic Policy Review, Vol. 10 (May), pp. 47–63.

Shen, P., 2006, “Liquidity Risk Premia and Breakeven Inflation Rates, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,” Economic Review, Second Quarter, pp. 29–54.

Additional information

*Tamim Bayoumi is a senior advisor with the IMF Strategy, Policy, and Review Department, and Andrew Swiston is an economist with the IMF Western Hemisphere Department. The authors gratefully acknowledge extremely helpful comments on this paper from two seminars at the IMF.

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Figures A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8, A9, A10, A11 and A12 show impulse-response functions up to a horizon of 50 days. Interest rates and inflation expectations are expressed in percentage points. The figures show the response, in percentage points, of the first variable listed to a one standard deviation shock in the second variable listed. The ordering of the Cholesky decomposition used to identify shocks to each variable is RUS, PUS, R*, P* in Figures A1, A2, A3, A4, A5 and A6; RUS, R*, P*, PUS in A8, A9, A10, A11 and A12; and R*, P*, RUS, PUS in A7, A8, A9 and A10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bayoumi, T., Swiston, A. The Ties that Bind: Measuring International Bond Spillovers Using Inflation-Indexed Bond Yields. IMF Econ Rev 57, 366–406 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2009.13

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2009.13