Abstract

Do financial crises promote or hamper transatlantic regulatory cooperation in banking? This article argues that financial crises have an impact upon the alignment of regulatory preferences of the United States (US) and the European Union (EU), causing an ‘ebb and flow’ in transatlantic cooperation. When EU-US preferences are broadly aligned in periods of financial stability, transatlantic regulatory cooperation is intense. It is relatively easy for the EU and US to agree on market-friendly regulation promoted by banks. When preferences are different, especially in the context and aftermath of the exogenous shock of financial crises, transatlantic cooperation is more problematic because crises re-assert the importance of nationally embedded patterns of market organisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Notes

See Ahearn, R.J. (2009) Transatlantic regulatory cooperation: Background and analysis. CRS Report for Congress, August. Washington DC: Congressional Research Service, http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL34717.pdf, accessed 31 March 2015. See also Pollack, M.A. (2003) The political economy of the transatlantic partnership. RSCAS, EUI, report, www.eui.eu/Documents/RSCAS/e-texts/200306HMTMvFReport.pdf, accessed 31 March 2015.

US policy-makers prefer the expression ‘substituted compliance’ instead of ‘mutual recognition’. The EU often uses the concept of ‘equivalence’ (See Ferran, E. (2012) Crisis-driven regulatory reform: Where in the world is the EU going? In: E. Ferran, N. Moloney, J.G. Hill and J.C. Coffee, Jr. (eds.) The Regulatory Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Qaglia, L. (2015) ‘The politics of “third country equivalence” in post-crisis financial services regulation in the European Union’, West European Politics 38(1): 167–184.), whereby if third country rules are deemed to be equivalent to EU rules, foreign firms providing services in the EU are not subject to EU regulation in addition to their home country regulation. Mutual recognition does not necessitate reciprocity, though de facto this is often the case (see Verdier, P.H. (2011) Mutual recognition in international finance. Harvard International Law Journal 52(1): 55–109).

See Verdier (2011); Schmidt, S.K. (2007) Mutual recognition as a new mode of governance. Journal of European Public Policy 14(5): 667–681.

The use of ‘exemptions’ is also a weak form of mutual recognition, whereby regulators in one jurisdiction exempt foreign firms operating in their territory from the application of certain domestic rules.

Harmonisation could also take place bilaterally, though this is less frequent and is generally part of the process of mutual recognition.

See Drezner, D.W. (2007) All Politics Is Global: Explaining International Regulatory Regimes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; Simmons, B. (2001) The international politics of harmonisation: The case of capital market regulation. International Organization 55(3): 589–620; Singer, D.A. (2007) Regulating Capital: Setting Standards for the International Financial System. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Helleiner, E. (2010) A Bretton Wood moment? The 2007–2008 crisis and the future of global finance. International Affairs 86 (3): 619–636, Helleiner, E. and Pagliari, S. (2009) Towards a new Bretton woods? The first G20 leaders summit and the regulation of global finance New Political Economy 14(2): 275–287. Trachtman, J.P. (2010) The international law of financial crisis: Spillovers, subsidiarity, fragmentation and cooperation Journal of International Economic Law 13(3): 719–742.

On the one hand, one could argue that the fact that the US and the EU (and its member states) are able eventually to reach an international agreement, despite having very different preferences and after controversial negotiations, is evidence of cooperation. On the other hand, the agreements reached in this way are often based on the minimum common denominator, and are more likely to be implemented with substantial divergence at the level of the jurisdiction. This is transatlantic cooperation of low intensity.

For an exception, see Quaglia, L. (2014) The European Union and Global Financial Regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Quaglia, L. (2014) The European Union, the USA and international standard setting in finance. New Political Economy 19(3): 427–444.

The BCBS brings together national central banks and banking supervisors from the countries in the Group of Twenty (G-20). Before the international financial crisis, the BCBS included representatives from the Group of Ten (G-10).

Kapstein, E. (1989) Resolving the regulator’s dilemma: International coordination of banking regulations. International Organization 43 (2): 323–347, Kapstein, E. (1992) Between power and purpose: Central bankers and the politics of international regulation. International Organization 46(1): 265–287; Singer (2007); Simmons (2001).

Tsingou, E. (2008) Transnational private governance and the Basel process: Banking regulation and supervision, private interests and Basel II. In: J.-C. Graz and A. Noelke (eds.) Transnational Private Governance and Its Limits. London: Routledge, Lall, R. (2012) From failure to failure: The politics of international banking regulation. Review of International Political Economy 19(4): 609–638; Underhill, G.R.D. and Zhang X. (2008) Setting the rules: Private power, political underpinnings, and legitimacy in global monetary and financial governance. International Affairs 84(3): 535–554; Wood, D. (2005) Governing Global Banking: The Basel Committee and the Politics of Financial Globalisation. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Howarth, D. and Quaglia, L. (2015) The comparative political economy of Basel III in Europe and regulators’ ‘trilemma’. University of Edinburgh School of Law, Research Paper Series No 2015/19; Europa Working Paper No 2015/03; available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2630555; Young, K.L. (2012) Transnational Regulatory Capture? An empirical examination of the transnational lobbying of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Review of International Political Economy 19(4): 663–688.

Posner, E. (2009) Making rules for global finance: Transatlantic regulatory cooperation at the turn of the millennium. International Organization 63 (4): 665–699, Posner, E. (2010) Sequence as explanation: The international politics of accounting standards. Review of International Political Economy 14(4): 639–664; Leblond, P. (2011) EU, US and international accounting standards: A delicate balancing act in governing global finance. Journal of European Public Policy 18(3): 443–461; Pagliari, S. (2013) A wall around Europe?: The European regulatory response to the global financial crisis and the turn in transatlantic relations. Journal of European Integration 35(4): 391–408; Quaglia (The European Union and Global Financial Regulation); for an exception, see Dür, A. (2011) Fortress Europe or open door Europe? The external impact of the EU’s Single Market in financial services. Journal of European Public Policy 45(5): 771–787.

See Kapstein (1989, 1992).

See Howarth and Quaglia (2015).

See Drezner (2007).

See Tsingou, (2008) Underhill and Zhang (2008), Young, (2012) Young (this special issue).

See Hardie, I. and Howarth, D. (eds.) (2013) Market-Based Banking and the International Financial Crisis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, See also Howarth and Quaglia (2015).

Grossman, E. and Woll, C. (2013) Saving the banks: The political economy of bailouts. Comparative Political Studies, on-line first, June, 10.1177/0010414013488540. Woll, C. (2014) The Power of Inaction: Bank Bailouts in Comparison. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Culpepper, P. (2011) Quiet Politics and Business Power: Corporate Control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pagliari, S. (2013) Public salience and international financial regulation. Explaining the international regulation of OTC derivatives, rating agencies, and hedge funds. PhD dissertation, University of Waterloo, available at http://www.stefanopagliari.net/phd-thesis.html.

Pagliari, S. and Young, K.L. (2014) Leveraged interests: Financial industry power and the role of private sector coalitions. Review of International Political Economy 21 (3): 575–610.

Widmaier, W., Blyth, M. and Seabrooke, L. (2007) Exogenous shocks or endogenous constructions? The meanings of wars and crises. International Studies Quarterly 51 (4): 747–759.

Büthe, T. and Mattli, W. (2011) The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

See Posner (2009) See also Bach, D. and Newman, A.L. (2007) The European regulatory state and global public policy: Micro-institutions, macro-influence. Journal of European Public Policy 14(6): 1–20.

See Drezner (2007) and Dür (2011).

Quaglia, L. (2014) The sources of European Union influence in international financial regulatory fora. Journal of European Public Policy 21 (3): 327–345.

Eberle, D. and Lauter, D. (2011) Private interests and the EU-US dispute on audit regulation: The role of the European accounting profession. Review of International Political Economy 18 (4): 436–459.

See Simmons (2001) and Wood (2005).

Meunier, S. and Nicolaïdis, K. (2006) The European Union as a conflicted trade power. Journal of European Public Policy 13 (6): 906–925.

See Wood (2005).

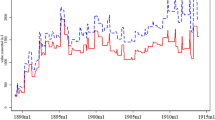

World Bank (2015) Bank capital to assets ratio (%). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FB.BNK.CAPA.ZS, accessed 1 May 2015.

For 1988 (with the exception of Spain), see BIS (1999) ‘Capital Requirements and Bank Behaviour’, 1,, Basel: BIS, p. 7, available at http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs_wp1.pdf.

See Simmons (2001).

See Kapstein (1992) and Wood (2005).

See Simmons (2001) and Singer (2007).

Underhill, G.R.D. (1997) The making of the European financial area: Global market integration and the EU single market for financial services. In: G.R.D. Underhill (ed.) The New World Order in International Finance. London: Macmillan.

Over time, the standards set by the BCBS came to be applied in over 100 countries, well beyond the limited number of signatories.

To be sure, before the International Banking Act of 1978, foreign (including European) banks, where exempted from the geographical restrictions imposed on US banks. Following the International Banking Act of 1978, such restrictions were extended to foreign (including European) banks.

Story, J. and Walter, I. (1997) Political Economy of Financial Integration in Europe: The Battle of the System. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

ibid.

See Dür (2011).

See Underhill and Zhang (2008) and Tsingou (2008).

See Lall (2012) and Young (2012).

Tarullo, D.K. (2008) Banking on Basel: The Future of International Financial Regulation. Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Interviews, Frankfurt, 17 January 2006; Rome, 23 June 2006.

Baker, A. (2010) Restraining regulatory capture? Anglo-America, crisis politics and trajectories of change in global financial governance. International Affairs 86 (3): 647–663, Mügge, D. (2011) From pragmatism to dogmatism: European Union governance, policy paradigms, and financial meltdown. New Political Economy 16(2): 185–206.

Christopoulos, D. and Quaglia, L. (2009) Network constraints in EU banking regulation: The case of the capital requirements directive. Journal of Public Policy 29 (2): 1–22.

See, for example Paletta, D. (2005) Backlash on Basel hits Fed – What now? American Banker, 6 October. Sloan, S. (2006) Why big banks’ Basel tactics may not work. American Banker 10 October.

See, for example House Committee on Financial Services (2003) The new Basel accord – Sound regulation or crushing complexity? 27 February.

See Herring, R.J. (2007) The rocky road to implementation of Basel II in the United States. Atlantic Economic Journal 35 (4): 411–429.

See http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/tarullo20121128a.htm#fn3.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Division of Banking Supervision and Regulation (2001) Application of the board’s capital adequacy guidelines to bank holding companies owned by foreign banking organizations. Supervision and Regulation Letter 01–01, 5 January.

The Economist, Base camp Basel, 23 January 2010, p. 9.

Financial Times, International economy: A display of disunity, 22 October 2010, p. 9; Financial Times, Fears for German banks under new rules, 10 September 2010, p. 21.

UK banks were better positioned than it appears on Table 1 if data on Tier 1 capital are considered.

Howarth, D. and Quaglia, L. (2013) Banking on stability: The political economy of new capital requirements in the European Union. Journal of European Integration 35 (3): 333–346.

Financial Times, Basel rules risk punishing the wrong banks, 26 October 2010, p. 10.

Howarth, D. (2013) France and the international financial crisis: The legacy of state-led finance. Governance 26 (3): 369–339.

Extensive lobbying from the financial industry also accounts for this watering down of the rules. See Young (this special issue).

See Woolley, J.T. and Ziegler, J.N. (2012) The two-tiered politics of financial reform in the United States. In: R. Mayntz (ed.) Crisis and Control: Institutional Change in Financial Market Regulation. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Acharya, V.V., Cooley, T.F., Richardson, M.P. and Walt, I. (2011) Regulating Wall Street: The Dodd–Frank Act and the New Architecture of Global Finance. New Jersey: Wiley and Sons.

Macartney and Jones, this issue. Germain, this issue.

See http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/tarullo20121128a.htm#fn7.

See section ‘Intense “market-friendly” transatlantic regulatory cooperation in banking in the late 1990s and mid-2000s’.

See http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/tarullo20121128a.htm#fn7.

Tarullo, D.K. (2011) Capital and liquidity standards, before the committee on financial services. U.S. House of Representatives, Washington DC, 16 June. Tarullo, D. K. (2012) “Regulation of Foreign Banking Organizations,” Speech at Yale School of Management Leaders Forum, New Haven 28 November.

Financial Times, EU Warns US on Financial Protectionism, 22 April 2013, p. 9.

Wall Street Journal, 23 April 2013, http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/04/23/eus-barnier-pulls-no-punches-in-attack-on-u-s-bank-rules/.

See Introductory article.

Quaglia, L., Eastwood, R. and Holmes, P. (2009) The financial turmoil and EU policy cooperation 2007–8. Journal of Common Market Studies Annual Review 47 (1): 1–25.

See Helleiner (2010) and Helleiner and Pagliari (2009).

Acknowledgements

Lucia Quaglia wishes to acknowledge financial support from the British Academy and Leverhulme Trust (SG 120191) and the Fonds National de la Recherche in Luxembourg (Mobility-in fellowship). Part of the research for this article was conducted while she was Visiting Fellow at the Hanse Wissenschaftskolleg. The authors would also like to thank Huw Macartney, Rachel Epstein and the other contributors to this special edition, for their helpful comments and constructive criticism on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howarth, D., Quaglia, L. The ‘ebb and flow’ of transatlantic regulatory cooperation in banking. J Bank Regul 17, 21–33 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/jbr.2015.21

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jbr.2015.21