Abstract

The prolonged war in Iraq, the political turmoil in Lebanon, the heightened tension between the Israelis and the Palestinians, and the spectre of an attack on Iran have significantly increased business uncertainty in several countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Sovereign risk — the credit risk assessment to the obligations of central governments — is believed to have increased. In response, credit rating agencies like Moody's and Standard and Poor's have revised their ratings or placed specific countries on their watch lists, a move that normally precedes a credit rating change. Using data from Morgan Stanley and Euromoney, we propose to quantify and explain the variability of sovereign risk in five MENA countries and two control countries between 2002 and 2006 using a set of dates in which a tragic event has taken place. Our methodology will allow us to test the extent to which the heightened political tension in the Middle East has altered the risk profiles of these countries and to challenge the assumptions made by rating agencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The prolonged war in Iraq, the political turmoil in Lebanon, the heightened tension between the Israelis and the Palestinians, and terrorists bombings in Casablanca and Sharm el-Sheikh have altered the investment climate in several countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Sectors such as tourism and foreign and capital investments have been mauled, hurting the economies of several tourism-dependent countries like Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Morocco. Compounding the problem are the ongoing spectres of a Syrian–Israeli war, the Iranian nuclear challenge, and the recent civil strife in Gaza, among others. All these events have cast dark shadows on the region's financial sectors, with aftershocks reverberating in their stock exchanges and the private sector carrying the brunt of these adverse effects. As a result, sovereign risk — the credit risk assessment to the obligations of central governments — in several MENA countries has risen considerably, causing a conspicuous increase in the cost and availability of capital for lending and investment.

A combination of heightened political tension since 2001 and record oil prices has influenced sovereign risk in the MENA region in two different directions. As MENA governments borrow in the international bond markets, credit ratings by Standard and Poor's and Moody's are becoming significantly important and have enabled several governments to gain access to international bond markets. The history of credit agencies is, however, fraught with disagreement and controversy over specific rating assignments, primarily because of the difficulty of assessing sovereign risk. With conflicting factors at play, two questions emerge: (1) how did the combination of political tensions and improved economies impact the MENA region as a whole and (2) to what extent did investors' risk assessments change as evidenced in the sovereign risk premium they require.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The existing literature on sovereign risk is broad and well developed, but for the MENA region it is scant, consisting primarily of trade publications of major investment banks (Morgan Stanley, Morgan, Credit Suisse, etc). For Latin America and Asia, however, the literature list is long.1, 2, 3 By and large, these studies investigated whether the debt crises were exacerbated by the less developed countries' (LDCs) insolvency or market illiquidity. Ramcharran4 identified those sovereign credit ratings as the primary determinants of loan prices on the secondary market. An earlier study by Cantor and Packer,5 however, showed that there is significantly more disagreement between rating agencies in their assessments of credit risk for low-quality sovereigns than for similar quality US corporate credits. A more updated analysis was presented in a model by Ferrucci,6 with the aim of assessing whether sovereign risk was ‘overpriced’ or ‘underpriced’ during different periods of the 1990s. His results suggest that a debtor country's fundamentals and external liquidity conditions are important determinants of market spreads. A country's creditworthiness, however, is found to be more broad based than that provided by the set of economic fundamentals. In the context of MENA countries, Haddad and Hakim7 recently presented an econometric analysis based on a panel study of five countries (Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey). Their findings reveal that the temporal fluctuation in sovereign spreads is explained by changes in the current account, the assigned rating from the rating agencies, and per capita income.

Political events impact financial markets, and the literature on sovereign debt shows a link between political risk and sovereign risk. Some studies distinguish between a country's ability to pay and a country's willingness to pay its debt. Repayments in arrears of sovereign debt can hardly be enforced legally, and the honouring of contractual obligations becomes a matter of cost–benefit analysis for governments. If the costs of repayment outweigh the benefits of repayment, the debtor country will interrupt its debt servicing. Kaminsky and Schmukler8 find that nearly one-fifth of the largest stock price movements during the Asian crisis were associated with news of a political nature. Zoli9 finds that the Brazilian government's announcements to raise the public sector surplus as well as concrete fiscal policy actions, such as budgetary cuts, implied a reduction in the perceived risk of default during the ‘confidence crisis’ of 2002–2003. Baig et al.10 extend the mentioned analysis and observe similar results for Poland but mixed results for Turkey. Bussiere and Mulder11 show that political instability has a strong influence on economic instability for countries with weak economic fundamentals and low international reserves. Chang12 presents a theoretical structure that allows for the instantaneous determination of financial and political crises.

To summarise the preceding studies, it appears that since 1999, the literature has taken a slightly different tone in an attempt to investigate the role of internal politics and how it enters into the agency risk assessments, particularly when there is a perceived transition in government. Recent empirical studies on macroeconomic determinants of agency ratings by McNamara and Vaaler,13 Vaaler and McNamara,14 and Block et al.15 yield results consistent with this view.

Our study elaborates on this literature in two directions: (1) we tie in a country's political events and debt indicator variables directly to the yield spread on its Eurobond issues and (2) we test whether and by how much the political tensions since 2002 have created a shift in risk perception across selected MENA countries. These tests are critical for governments to evaluate how their sovereign risk is being priced in the international bond market, and, if necessary, enable them to challenge any rating change by the agencies. At the same time, the results are also useful for investors (either private individuals or international bond funds) to better anticipate how sovereign spreads, therefore a country's risk, correlate with specific economic and political events.

PROPOSED DATA AND METHODOLOGY

We estimate the determinants of sovereign risk in five MENA and two non-MENA countries in a panel setting using cross-sectional and time series data on credit spreads derived from Eurobond issues. The methodology enables us to determine the evolution of sovereign risk over time and test whether a fundamental repricing of risk in specific MENA countries has occurred as a result of the following events:

-

1)

the invasion of Iraq (March 2003),

-

2)

the suicide bombings in Casablanca (May 2003),

-

3)

the murder of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri (February 2005),

-

4)

the attacks on Sharm el-Sheikh (July 2005), and

-

5)

the Israeli war on Lebanon (July 2006).

Two recent events in 2007, namely (a) the bombing in Algeria allegedly claimed by ‘al-Qaeda's branch in Islamic North Africa’ (April 2007) and (b) the suicide bomb attack in Ankara (May 2007) are worth investigating. Our economic data end, however, in December 2006, before these developments had taken place, and this prevents us from statistically testing their impact on sovereign yields.

Our analysis enables us to quantify the additional cost premium these MENA countries had to bear as a result of any shift in market perception from each of the five preceding events. While there were other terrorist attacks in MENA countries since September 11 (eg Jordan and Saudi Arabia), these preceding events should capture the main shocks that have exacerbated the economic risks in each country. The model's explanatory variables consist of

-

a)

The sovereign yield spread on Eurobonds from Morgan.16

-

b)

Scores of political rights and civil liberties collected by Freedom House in Washington, DC.17 We calculate the average of the two scores and use it as a measure of freedom in each country.

-

c)

Monthly changes in a proxy for the stock market index of each country converted to US$. The proxies are constructed by S&P/IFCG18 (Global) indices and represent the performance of the most active stocks in their respective emerging markets. As a core member of the S&P Emerging Market indices, the proxies are constructed from equities included in the Emerging Markets Database (EMDB) of S&P/IFCG. The data are also available through Bloomberg.

-

d)

Foreign bond ratings available from Moody's and Standard and Poor's.

-

e)

And finally, a vector of country-specific economic indicators collected by the World Bank. The vector includes

-

Current account balance (as a per cent of GDP). The current account records all inflows and outflows of income derived from exporting and importing goods and services, net income from investment and employee compensation, and unilateral transfers.

-

Total debt service as a per cent of gross national income.

-

Total gross national income (GNI) per capita, Atlas method (current US$).

-

External debt, total (current US$) relative to total exports of goods and services.

-

The sample also includes two non-MENA countries (Brazil and South Africa), allowing for comparative analysis.

Because our data contain information on cross-sectional units (countries) observed over time, a panel data estimation technique is adopted. This allows us to perform statistical analysis and apply inference techniques in either the time series or the cross-section dimension. The model takes the following form:

where i=1, 2, …, N cross-sections and periods t=1,2, …, T, with T=60 monthly periods (from January 2002 to December 2006) and N=(seven countries — five MENA countries, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey and two control countries — Brazil and South Africa). SR it represents the sovereign risk premium to a US Treasury security of comparable maturity, and x it is a vector of independent variables. Several dummy variables are used to test the statistical significance of the preceding five (war and terrorism) events and contrast any change in sovereign risk in MENA vs. Brazil and South Africa. The elements of the dummy vector take the value 0 or 1, depending on whether the war or terrorist event has taken place. We also provide a Wald test of the joint statistical significance of the seven coefficients associated with each dummy variable to determine if the war/terrorism event had any impact beyond a single country or the MENA region.

ANALYSIS OF EMPIRICAL RESULTS

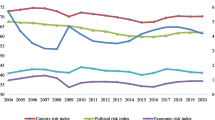

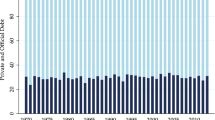

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of our sample data and Figure 1 provides a plot of the sovereign spread during the study period. Table 2 shows a cross-country comparison of the freedom variables across countries. Both South Africa and Brazil enjoy a higher freedom score than any of the MENA countries in our sample.

The panel study estimation results are summarised in Table 3. The current account and debt service variables are key. Both are signed correctly and highly significant. Specifically, a higher debt service (relative to GNI) increases the risk of default and therefore has a positive impact on the sovereign yield spread a country has to pay on the Eurobond market. The current account variable, which increases with higher exports (net of imports), has the opposite effect on the yield differential for a country. These results are consistent for all countries. Similarly, the GNI and the credit rating have the expected signs. A higher GNI (per capita) suggests more relative prosperity for a specific country and, consequently, a better repayment ability. Likewise, a higher credit rating indicates a lower likelihood of default. Both of these effects have a negative impact on the sovereign yield spread because they translate into a diminished sovereign risk premium. The equity market is also significant, suggesting that the stock market index, perhaps more than any other variable, tracks closely and drives the sovereign risk in a country. Specifically, a rising stock market index (in constant dollar terms) predicts higher earnings and a better economic outlook, all of which are expected to reduce the risk premia of a country on the international bond market. The total debt variable relative to exports is not statistically significant, and it is not possible to evaluate its sign effectively.

Turning to the dummy variables, the Iraq war seemed to have a selective impact on MENA countries. With the exception of Turkey, none of the countries we analysed seemed to have been impacted by the invasion of Iraq. The effect on Turkey, however, is not only highly statistically significant, but also economically pronounced. The magnitude of the dummy coefficient is positive and stands at 233, suggesting that the Iraq war forced Turkey to pay marginally 233 basis points (bp) more on its Eurobonds borrowing that it would have otherwise.

The ‘freedom’ variables representing a country's relative score in political rights and civil liberties worldwide are all highly significant. All the coefficients are positive, indicating that restrictions on individual freedom (measured as an increase in the freedom score) widen the sovereign yield spread for a given country. Comparing the magnitude of the coefficient across the seven countries in the model reveals that in MENA, Turkey stands to become the largest beneficiary of an improvement in freedom (measured by a 191 bp interest savings for each 1-point reduction in its freedom score), followed by Egypt (97 bp), Morocco (92 bp), Tunisia (88 bp), and Lebanon (86 bp). It is important to understand that these figures only represent the impact of a change in a country's freedom index on its sovereign yield spreads, and not that country's level of freedom on sovereign yields. For example, Tunisia is ranked 5.5 (on a scale of 1–7) according to Freedom House. In contrast, Turkey has a score of 3. Our results indicate that for an identical 1-point improvement in freedom, the sovereign spreads in Turkey would fall by 191 bp, more than twice that in Tunisia (88 bp). For the five MENA countries, the average impact is 111 bp. It is beyond the scope of this paper to analyse the specific reasons why the financial impact of political rights and civil liberties varies so markedly across MENA countries, but it would appear that the higher a country's score, the smaller the marginal impact on sovereign spreads. Indeed, South Africa and Brazil, two countries in our sample with scores lower than Turkey, could reap the most financial benefit from a further improvement in their freedom scores.

By and large, the dummy variables relevant to terrorist events in MENA are all insignificant. It appears that the world bond market has shrugged off these events and that the yield spreads have acquired a sort of immunity against similar events in a country caught as a victim of such tragedies. The Lebanese and Moroccan Eurobonds do not seem to be impacted by the terrorist bombing in Casablanca (May 2003), the murder of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri (February 2005), or Israel's declared war on Lebanon (July 2006). For reasons we cannot explain, the spread on Egypt's Eurobonds has actually improved following the attack on Sharm el-Sheikh in July 2005. It would appear that the Eurobond market has experienced an event unrelated to the variables in our model.

To better evaluate the collective impact of the dummy variables, we conducted a Wald test of the joint significance of the dummy variables. Specifically, our null hypothesis is: H0: the country dummy vectors relevant to war and terrorism=0 against the alternative H1: the relevant dummy vectors are≠0. The resulting F-tests are provided in Table 4 and indicate that H0 is only statistically rejected in the context of the coefficients of the dummy vector for the Iraq war and the bombing in Casablanca.19 Taken collectively, the results of the joint test of the dummy vectors indicate that the Iraq war has indeed produced a fundamental shift in risk perception in MENA and beyond. While the impact on sovereign spreads for each individual country was not felt directly, the joint impact on the MENA region is statistically significant, and in the case of Turkey, the effect was both large in magnitude and statistically significant.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Sovereign risk ratings (‘ratings’) published by agencies facilitate credit transactions for developing country borrowers because the letter grade ratings are commonly relied on by capital market participants to assess both the specific capability and willingness of governments to honour their debts, and more general risks associated with lending and investment in the locale. While the agency ratings are significant, our study has demonstrated that the sovereign yield spreads, a direct measure of a country's sovereign risk, are far more complex and vary with many factors beyond what a simple credit rating can possibly capture. Specifically, the current account, the debt service, the level of national income, and the change in the stock market index are equally valid drivers for a country's risk rating. These simple factors should, therefore, be incorporated in assessing a country's risk profile alongside a country's credit rating offered by Standard and Poor's or Moody's.

Perhaps more telling is a country's freedom score and its impact on sovereign yield spreads. Our results suggest that the average impact of a 1-point improvement in the region's freedom index translates into a 111 bp savings on its cost of borrowing on the international bond markets. With the debt servicing for the five MENA countries averaging $44bn annually (from Table 1), improvement in political rights and civil liberties could generate substantial interest savings and provide a major boon to strained fiscal budgets.

Another important result of this paper is the extent to which war and terrorism have produced an impact on the region's financial markets. It would appear that with the exception of Turkey, the region has been relatively unscathed from these tragic events. We find evidence that the region's Eurobond markets have become somewhat immune to war and terrorism, and the sovereign spread (or risk premium) on most MENA countries under study remained constant after a major war or terrorist incident in the Middle East. Consequently, MENA countries may not be too concerned if they maintained their level of sovereign risk exposure ahead of any expected war or major political event. This is contrary to the widespread perception among market participants that a war or a terrorist incident may lead to arbitrage opportunities of a country's sovereign spreads.

As noted earlier, Turkey was a major exception to this conclusion. At the eve of the launch of the Iraq war, Turkey's external debt stood at $145bn with a debt service of $28bn, representing 19 per cent of its total external debts (from Table 1). Our results show that the impact of the war alone has raised Turkey's cost of borrowing by 233 bp. This factor translates into an additional $65m annually that Turkey has had to pay on the world bond markets to meet its borrowing needs. Clearly, the impact of the Iraq war has not been uniform across the MENA region.

Developing countries seek to finance their growth strategies by attracting mobile investment capital in a global economy. In this effort, the sovereign ratings are of central concern to policy makers who recognise the importance of the divergent interests of foreign investors and host states and the resulting risks they perceive over time. The ratings, however, do not provide a complete picture and should, therefore, be used as one of several factors to assess the perceived risks in a given country. Our results are expected to help policy makers in MENA countries to (1) better understand how financial markets are pricing their Eurobonds, (2) clearly identify the specific risk bins that influence their credit spreads, and (3) implement mitigation techniques to reduce their sovereign risk.

References and Notes

Boehmer, E. and Meggison, W.L. (1990) ‘Determinants of Secondary Market Prices for Developing Country Syndicated Loans’, Journal of Finance, Vol. 5, pp. 1517–1524.

Erb, C., Harvey, C. and Viskanta, T. (1994) ‘National Risk in Global Fixed-Income Allocation’, Journal of Fixed Income, September, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 17–26.

Hargis, K., Petry, J. and Trebat, T. (1998) ‘Finding Relative Value in Emerging Markets’, Emerging Markets Quarterly. Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 65–74.

Ramcharran, H. (1999) ‘The Determinants of Secondary Market Prices for Developing Country Loans’, Global Finance Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 161–175.

Cantor, R. and Packer, F. (1996) ‘Determinants and Impact of Sovereign Credit Ratings’, Federal Reserve Bank of NY, Economic Policy Review, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 37–53.

Ferrucci, G. (2003) ‘Empirical Determinants of Emerging Market Economies’ Sovereign Bond Spreads’, Working Paper, No. 205, November 2003, Bank of England.

Haddad, M. and Hakim, S.R. (2007) ‘The Cost of Sovereign Lending in the Middle East after September 11’, Journal for Global Business Advancement, Vol. 01, No. 01, pp. 127–139.

Kaminsky, G. and Schmukler, S. (1999) ‘What Triggers Market Jitters? A Chronicle of the Asian Crisis’, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 18, pp. 537–560.

Zoli, E. (2005) ‘How Does Fiscal Policy Affect Monetary Policy in Emerging Market Countries?’, BIS Working Paper, No. 174.

Baig, T., Kumar, M., Vasishtha, G. and Zoli, E. (2006) ‘Fiscal and Monetary Nexus in Emerging Market Economies: How Does Debt Matter?’, IMF Working Paper, No. 06/184.

Bussiere, M. and Mulder, C. (2000) ‘Political Instability and Economic Vulnerability’, International Journal of Finance and Economics, Vol. 5, pp. 309–330.

Chang, R. (2005) ‘Financial Crises and Political Crises’, NBER Working Paper, No. 11779.

McNamara, G. and Vaaler, P.M. (2000) ‘Competitive Positioning and Rivalry in Emerging Market Risk Assessment’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 31, pp. 337–349.

Vaaler, P.M. and McNamara, G. (2004) ‘Crisis and Competition in Expert Organizational Decision Making: Credit-Rating Agencies and their Response to Turbulence in Emerging Economies’, Organization Science, Vol. 15, pp. 687–703.

Block, S.A., Vaaler, P.M. and Schrage, B.N. (2006) ‘Opportunism, Partisanship and Sovereign Ratings in Developing Countries’, Review of Development Economics, Vol. 1, No. 10, pp. 154–174.

Morgan, J.P. (2006) ‘Emerging Markets Outlook and Strategy for 2007’, J.P. Morgan Securities Inc., 22nd November, 2006.

Freedom in the World: Freedom House, Washington, DC, http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=1.

Standard and Poor's/IFCG Market Indices: Available through http://www2.standardandpoors.com/portal/site/sp/en/us/page.topic/indices_ifcg/2,3,2,9,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0.html or through Bloomberg.

These two events are only a few months apart and it is possible that the latter effect is picking up a residual statistical noise from the dummy vector of the Iraq way.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Practical applications Our results can be utilized by policy makers, credit rating agencies, financial analyst, portfolio managers, risk managers and hedge funds managers.

1 Mahmoud Haddad is a professor of Finance at the College of Business and Public Affairs, University of Tennessee, Martin. He has published over 25 papers in leading refereed journals. He was the Financial and Accounting Manager at the American Family Insurance Co., the Executive Director of Research at the Palestinian Monetary Authority, the Vice President for Administrative and Financial Affairs and Dean of College of Business and Financial Sciences at the Arab American University, and a research scholar and Head of Economic and Social Studies Division at the Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research.

2 Sam Hakim is a vice president of Risk Management at the Energetix in Los Angeles. He is concurrently an adjunct professor of Finance at the Pepperdine University in Malibu, California. He is the author of more than 40 articles and publications. He is an Ayres fellow with the American Bankers Association in Washington, DC, and a fellow with the Economic Research Forum. He holds a PhD degree in Economics from the University of Southern California.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haddad, M., Hakim, S. The impact of war and terrorism on sovereign risk in the Middle East. J Deriv Hedge Funds 14, 237–250 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2008.17

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2008.17