Abstract

We find that leverage in exchange traded funds (ETFs) can affect the ‘crookedness’ of volatility smiles. This observation is consistent with the intuition that return shocks are inversely correlated with volatility shocks – resulting in more expensive out-of-the-money put options and less expensive out-of-the-money call options. We show that the prices of options on leveraged and inverse ETFs can be used to better calibrate models of stochastic volatility. In particular, we study a sextet of leveraged and inverse ETFs based on the S&P 500 index. We show that the Heston model can reproduce the crooked smiles observed in the market price of options on leveraged and inverse leveraged ETFs. We show further that the model predicts a leverage-dependent moneyness, consistent with empirical data, at which options on positively and negatively leveraged ETFs (LETF) have the same price. Finally, by analyzing the asymptotic behavior for the implied variances at extreme strikes, we observe an approximate symmetry between pairs of LETF smiles empirically consistent with the predictions of the Heston model.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Empirical motivation

By relating option prices to observables (such as strike prices, time-to-expiration, spot price and so on) and one unknown parameter (implied volatility of the underlying asset return dynamics), Black and Scholes (1973) allowed practitioners to more systematically study observed option prices. Furthermore, this unknown parameter allowed researchers to normalize comparisons between options with different observables.

For all of the success of the Black-Scholes model and for its near-ubiquity today, there are several shortcomings of the model. For example, Rubinstein (1985) pointed out strike price biases and close-to-maturity biases by studying the prices of the most active option on the CBOE.Footnote 1 In subsequent works, Rubinstein (1994) and Jackwerth and Rubinstein (1996) showed that options on stocks and stock options exhibit volatility skew and that foreign currency options exhibit a volatility smile (at-the-money options are cheaper than in-the-money or out-of-the-money options).

In Figure 1, we show a typical volatility smile for call options on equities and equity indices.Footnote 2 The volatilities implied by the prices of in-the-money options is higher than the volatility implied by the prices of at-the-money options which is higher than the volatility implied by the prices of out-of-the-money options.

In this article, we study the implied volatility surface of options on leveraged ETFs (LETFs) and inverse leveraged ETFs (ILETFs). In particular, we consider members of a sextet of exchange traded funds (ETFs) tracking the S&P 500 index. See Table 1 for the names, tickers and corresponding leverage factor (ℓ).The daily percentage change in the net asset value of an ETF with leverage factor ℓ is ℓ times the daily percentage change of the underlying index.Footnote 3 LETFs have leverage factor ℓ⩾1, whereas ILETFs have leverage factor ℓ⩽−1.Footnote 4

According to the Black-Scholes model, an option on an LETF with leverage factor ℓ⩾1 should have the same price as an option on an ILETF with leverage factor (−ℓ) if both options share the same strike price and expiration – if these ETFs share the same underlying index.Footnote 5 This is intuitive because, in risk-neutral valuation, the only difference between the evolution of the LETF or ILETF is the leverage factor that proportionally increases the volatility. Since the option price is dependent on the square of the volatility, the price of options on LETFs and ILETFs with the same strike and expiration should have the same price.

In Figure 2(a), we show the volatility smile for options on an LETF with ℓ=3 and an ILETF with ℓ=−3. The pattern of implied volatilities for ProShares UltraPro S&P 500 ETF (UPRO) is similar to the pattern of implied volatilies in Figure 1(a), with the volatilities of UPRO roughly three times the implied volatilities from options on SPY. On the other hand, the options on the inverse ETF (SPXU) have implied volatilities that are a decreasing function of the moneyness. Figure 2(a) shows that the prediction of the option prices under the Black-Scholes model is not consistent with empirical data.

Figure 2(b) shows the price of call options on these LETFs as a function of the normalized strike price. These observations suggest that the crookedness of the volatility smile is dependent on the leverage factor ℓ.

The prices of in-the-money call options on positively LETFs (ℓ1⩾1) imply lower volatilities than the prices of in-the-money call options on ILETFs (ℓ2⩽0) for the same level of leverage (ℓ1=|ℓ2|) and moneyness. Similarly, the prices of out-of-the-money call options on positively LETFs imply lower volatilities than the prices of out-of-the-money call options on ILETFs for the same level of leverage and moneyness.Footnote 6

Intuitively, we expect stock returns to be negatively correlated with volatility shocks – for example, large price decline and an increase in volatility. As a result, far from the money put options are more expensive than one may naively expect. As a result, the volatility implied by option market prices is increasing with decreasing moneyness, as shown in Figure 2(a). For an inverse ETF, stock returns would be positively correlated with volatility shocks – for example, large price declines in the underlying lead to large price increases in the inverse ETF. As a result, the volatility implied by option market prices on inverse ETFs should be increasing with increasing moneyness. The combination of these two arguments implies that low moneyness options on positively LETFs will be more expensive than similar options on negatively LETFs.

We explore this phenomenon, as well as the crossing phenomena shown in Figure 2(b), both empirically and theoretically in this article.Footnote 7 Although this phenomenon is intuitive, there has been no study of the crossing behavior depicted in Figure 2(b) and this article seeks to fill this gap.

Observable implications

We use the stochastic volatility model in Heston (1993) to explain the ‘crooked smiles’ in the options market. This Heston model, similar to the Black-Scholes model, has closed-form solutions for the valuation of European put and call options but incorporates stochastic volatility.

Unlike the constant implied volatility in the Black-Scholes model, the dynamics of the volatility is correlated with the dynamics of the stock price or index level in the Heston model. This stochastic volatility model is better equipped to account for observed skewness and kurtosis of return distributions.Footnote 8

Volatility smiles have often been explained either by jump-diffusion models as suggested by Merton (1976) or with stochastic volatility as in models proposed by Hull and White (1987) and Heston (1993). We consider the Heston model here because of the convenient analytic properties.

Option pricing in the context of LETFs has recently gained interest in the literature. Ahn et al (2012) and Zhang (2010) use standard transformation methods to price options on ETFs and LETFs within the Heston stochastic volatility framework. We extended their research by deriving the dynamics of LETFs. The closed-form solutions use a Green function approach following the method in Lipton (2001). Our numerical simulations show that the Heston model can explain the patterns in option prices on LETFs and ILETFs. We observe that the crooked smile is present only when there exists non-zero correlation between the Brownian motions for the asset returns and the variance.Footnote 9 Furthermore, we show that the model predicts a moneyness – dependent on the level of leverage – for which the prices of positively and negatively LETF options have the same price and that this prediction is consistent with empirical data.

We also study the asymptotic behavior of implied variance curves for options on LETF and ILETF. This analysis relies heavily on the moment expansion framework in Lee (2004) and Rollin et al (2009). Subsequent analyses – Friz et al (2011) and de Marco and Martini (2012) – refined the volatility smile expansion within the Heston model. Building on Lee’s work, Benaim and Friz (2009) showed how the tail asymptotics of risk-neutral returns can be directly related to the asymptotics of the volatility smile and they applied this approach to time-changed Lévy models and the Heston model (Benaim and Friz, 2008).

We provide empirical evidence that the asymptotic slopes of the implied variance curves for options on LETF and ILETF show an approximate symmetry and that this approximate symmetry is consistent with the Heston model. In particular, we show that the large-strike asymptotic slopes of the implied variance curves for LETFs are related to the small-strike asymptotic slopes of the implied variance curves for ILETFs. Both simulated examples and market data are presented.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: In the second section, we review the Black-Scholes model and Heston stochastic volatility model. The closed-form solution of the call options of LETF and ILETF is derived under Heston dynamics. In the third section, the asymptotic behaviors of the option prices are studied as the moneyness goes extremely large and small. In the fourth section, we simulate the option prices under Heston dynamics, and compare the prices across different leverage numbers ℓ. In addition, we calibrate our model using the empirical data in the fifth section. The article is concluded in the sixth section.

LEVERAGED AND INVERSE ETF OPTION PRICES

The Black-Scholes model

If an asset price St follows a geometric Brownian motion then its dynamics are described by the classic stochastic differential equation

where μ, q and σ are expected return, dividend yield and implied volatility of the asset, respectively. All three parameters are assumed to be constant and continuously compounded. The price of an LETF or ILETF Lt, which tracks ℓ times daily return of the underlying asset, satisfies

where μℓ=ℓμ and σℓ=ℓσ. This implies that the volatilities of the returns are leveraged |ℓ| times.

Under risk-neutral assumptions, the expected return of the LETFs μl is the risk-free rate r, independent of ℓ. Therefore, the option price C(t, L) satisfies the following Black-Scholes equation:Footnote 10

where r is the constant risk-free rate.

In this model, the volatility (the standard deviation for the instantaneous ETF return dLt/Lt) is always |ℓ|σ, and is independent of the strike price of the option contract, as well as the sign of the leverage number ℓ. If both LETF and ILETF have the same leverage factor in absolute value and the same dividend yield qℓ, we should observe the same implied volatility and same option price under the Black-Scholes model. Figure 2(b) shows that this theoretical prediction is inconsistent with observed market option prices.

Heston’s stochastic volatility model

Since the Black-Scholes model is not able to adequately describe the phenomena observed in the option prices on the sextet of LETFs in the section ‘The Black-Scholes Model’, we turn to alternative models of asset dynamics. We choose to discuss the Heston model (Heston, 1993) in particular because of the closed-form solutions for European option prices and the depth of literature analyzing the details of the model.

In the risk-neutral framework, we write Lt as the price of the LETF or ILETF, vt as the variance of the underlying stock. These variables are governed by the dynamics

where W1t and W2t are two Brownian motions with a correlation value ρ, that is,

A simple derivation shows that the stochastic process Lt is linked to the underlying stock price process St and the realized variance ∫0tvtdt

The equation implies that a higher realized variance implies a larger deviation between the holding period returns of LETFs and those of the underlying stock. Although the equation cannot be directly used in valuing options on LETFs, it shows the necessity of using stochastic volatility models since dynamic variance is an important component of the return of LETFs.Footnote 11

Utilizing the following theorem, we derive the call option value for LETFs.

Theorem 1

-

The value of an European call option with strike K for an LETF in the Heston model is in the form

where v0 is the initial variance value at time 0 and τ is the time to maturity τ=T−t. Xt is defined as ln(Ft)/(K), where Ft is the forward price of LETF and is defined as Ft=Lte(r−q)τ. The function U(τ, Xt, v0) is given by equation (A.6) in Appendix.

Proof: See proof in Appendix. □

Alternatively, a single set of change variables could simplify the valuation approach. If we introduce the following change of variablesFootnote 12

The stochastic differential equations in equation (2) and equation (3) are converted into the following standard Heston model

Note that the new equations are free of the leverage factor ℓ thus we can use the Lipton solution or Heston solution given ℓ=1. Having derived the dynamics of leveraged and inverse ETFs based on the dynamics of the underlying index, we move on to consider the pricing of options on leveraged and inverse ETFs.

SYMMETRY IN IMPLIED VARIANCES FOR LETF OPTIONS

In this section, we study the implications of Andersen and Piterbarg (2007) to the extreme strike behavior of option prices on leveraged and inverse ETFs.Footnote 13 Our results build heavily on the work by Lee (2004), wherein the author showed that the extreme strike behavior is related to the number of finite moments of the return distribution.Footnote 14

In particular, at large strikes the Black-Scholes implied variance becomes a linear function of the logarithm of the strike price. Lee (2004) showed that the small-strike asymptotic behavior is also a linear function of the logarithm of the strike price using the properties of the inverse price process.

Following Friz and Keller-Ressel (2009), a model is said to exhibit moment explosion at order α>1 if there exists some finite T*(α) such that  . The time of moment explosion T*(α) depends on the moment under consideration and is the smallest time such that

. The time of moment explosion T*(α) depends on the moment under consideration and is the smallest time such that  If, for some β,

If, for some β,  is finite for all t then T*(β)=∞.

is finite for all t then T*(β)=∞.

Lee (2004) showed that the large-strike (K≫F0) Black-Scholes implied variance is related to the degree of moment explosion through the following theorem.Footnote 15

Theorem 2

-

If

and βR=limsupx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

and βR=limsupx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

Lee (2004) showed further that the extreme small-strike (K≪F0) asymptotic behavior of the Black-Scholes implied volatility can be related to the degree of moment explosion of the inverse price process through the following theorem.

Theorem 3

-

If

and βL=lim supx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

and βL=lim supx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

When βL or βR is 0, the underlying model does not exhibit moment explosion. Note that p*=α+*−1, where α+* is the degree of moment explosion or the critical moment for the process St at time T and q*=α−*, where α−* is the critical moment for the inverse price process ST−1 at time T.

Andersen and Piterbarg (2007), in their Proposition 3.1, show how to relate the degree of moment explosion α+ to the parameters in the Heston model as well as the time of moment explosion T*(α+). Following Corollary 6.2 in Andersen and Piterbarg (2007), the critical moment α+* is obtained by solving T*(α+)=T.

To solve the critical moment α−* for the inverse price process, Rollin (2008) showed that if an asset follows a price process described by the Heston model then the inverse spot price follows a price process described by the Heston model with the following parameters

where the parameters  represent the analogous parameters in the inverse spot price process to those in the non-inverted price process. Using these results, we can study the symmetry of Black-Scholes implied variances at extreme strikes for options on LETFs and ILETFs.

represent the analogous parameters in the inverse spot price process to those in the non-inverted price process. Using these results, we can study the symmetry of Black-Scholes implied variances at extreme strikes for options on LETFs and ILETFs.

Referring to the parameter translations in equation (7), we see that the LETF price process Lt, ℓ is closely linked to the inverse of the ILETF price process Lt, −ℓ, Lt, ℓ≈Lt, ℓ−1. The following table shows the corresponding parameters used for the two price processes when we combine the results in equation (7) with the result in equation (12) (Table 2).

The Heston model parameters  ,

,  and

and  are the same for both processes. In practice, the Heston model parameters

are the same for both processes. In practice, the Heston model parameters  and

and  are not exactly the same, but they are close. Therefore, the critical moments for the LETF price process α*+, ℓ approximates the critical moment for the inverse of ILETF process α*−, −ℓ. The theorems above predict that βR, ℓ≈βL, −ℓ. In other words, the ratio of the Black-Scholes implied variance to the moneyness of deep-in-the-money call options on LETFs equals the ratio of the Black-Scholes implied variance to the moneyness of deep-out-of-the-money call options on ILETFs of the same leveraged amplitude. The asymmetry between these two slopes is related to the volatility of variance (ε) and increases approximately linearly with the degree of leverage for small values of the volatility of variance. In the fourth and fifth sections, we will give two examples of critical moments and asymptotic slopes highlighting the relationships.

are not exactly the same, but they are close. Therefore, the critical moments for the LETF price process α*+, ℓ approximates the critical moment for the inverse of ILETF process α*−, −ℓ. The theorems above predict that βR, ℓ≈βL, −ℓ. In other words, the ratio of the Black-Scholes implied variance to the moneyness of deep-in-the-money call options on LETFs equals the ratio of the Black-Scholes implied variance to the moneyness of deep-out-of-the-money call options on ILETFs of the same leveraged amplitude. The asymmetry between these two slopes is related to the volatility of variance (ε) and increases approximately linearly with the degree of leverage for small values of the volatility of variance. In the fourth and fifth sections, we will give two examples of critical moments and asymptotic slopes highlighting the relationships.

NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS

Simulation parameters

In this section, we present numerical simulations to show the dependence of the leverage-skew on model parameters. By studying this dependence, we can hope to endow the reader with an understanding of the patterns predicted by the Heston model. For our numerical simulations, we fix the following parameters

In what follows, we vary the correlation ρ between returns and return variance, the leverage number ℓ, and the strike price K (or equivalently, the moneyness). By varying these parameters, we analyze the model and explain the pattern implied by market prices of options on leveraged and inverse ETFs. The model calibration on the empirical data will be discussed in the fifth section.

In Figure 3, we vary the strike price of the call option and show the call option price for each leverage number in {−3, −2, −1, 1, 2, 3} keeping the correlation fixed at ρ=−0.5. The call option prices are seen to be split into pairs, with the prices of the doublets {−ℓ, ℓ} being comparable.

The Heston model with the current set of parameters is ready to explain the volatility smile. Hull (2011) shows that the call option prices are a monotone increasing functions of the implied volatility. Hence, the higher the implied volatility, the higher the call option price.

Break-even strike prices

Call options that are deep-in-the-money, that is, K≪S0 on the LETF with leverage number ℓ>0 are more expensive than the same-strike call options on the ILETF with leverage number −ℓ. For options that are deep-out-of-the-money (K≫S0), the conclusion reverses: the option prices on the ILETF are more expensive than that on the LETFs.Footnote 16 These simulated curves are very similar to what we have observed in Figure 3(b). Both simulated and empirical curves imply that there exists a critical (or ‘break-even’) strike price (K*(|ℓ|)) at which the call option price of a LETF with leverage number ℓ>0 equals the call option price on a ILETF with leverage number −ℓ. Table 3 reports those critical strike prices that results in equality between the prices of options on LETFs and ILETFs within the same doublet (ℓ=±|ℓ|) for our numerical simulations. In this particular set of parameters, the break-even strike price/moneyness decreases as the leverage factor increases.

Table 3 demonstrates the dependence of the break-even prices on the leverage |ℓ|. In Figure 4, we plot the difference between call option prices on the LETF and ILETF within the same doublet for different values of the correlation coefficient ρ. This set of graphs shows that the price difference of the call options is symmetric with respect to ρ. The simulations further show that the break-even strike prices, when the option price differences equal zero, are independent of ρ.

Figure 4 make a few aspects of the phenomena predicted by this model clear.

-

If the correlation coefficient is 0, the difference between the call option prices is 0. In this case, the changes in the volatility are independent of the changes in the stock price. Hence the Heston model essentially becomes a Black-Scholes model with implied volatility being the expected mean volatility in the Heston model.

-

As ℓ increases, the difference between the prices of options on LETF and ILETF increases in magnitude. That can be partially explained that the higher volatility of the leverage funds, the higher option premium.

-

Upon changing the sign of ρ, the cheaper option becomes the more expensive option for fixed strike within the same doublet of ETFs.Footnote 17

-

The break-even strike price within each doublet is independent of ρ. Although we present only a handful of correlation examples in Figure 4, this conclusion holds for all values of ρ.

Note that deep-out-of-the-money call options on ILETFs are more expensive than deep-out-of-the-money call options on LETFs when ρ<0. If the correlation coefficient ρ is negative, the volatility and the price of ILETF tend to increase simultaneously. With the same parameters, the price of LETF increases, while the volatility tends to decrease. Intuitively, the ILETF option has a higher probability of ending in-the-money than the analogous LETF. As a result, the call option prices on an ILETF with high strike are often more expensive than call option prices on an LETF when stock price and implied volatility are negatively correlated.

Asymptotic implied variance slope

We explore the correspondence present between high-strike asymptotic behavior of positively LETFs and low-strike asymptotic behavior of negatively LETFs in Table 4. In this context, it is conventional to study implied variance – as opposed to implied volatility – since implied variance has an asymptotically linear relationship to the logarithm of the strike price while implied volatility has a non-linear asymototic relationship.

Note that βR, ℓ≈βL, −ℓ and the difference between these two is roughly proportional to ℓ. For example, βR, 3−βL, −3≈3(βR, 1−βL, 1). This correspondence can be seen graphically as an approximate reflection about the at-the-money line (K=S0) in Figure 5. The pair of lines corresponding to, for example, ℓ=3 roughly corresponds to those of ℓ=−3 on reflection about the line log(K/S0)=0.

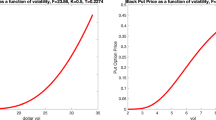

As an example of how this reflection works in practice, we plot the Black-Scholes implied variance as a function of the log-strike price in Figure 6 for the options priced using the Heston model. The large-strike slope of each implied variance curve is nearly parallel to the respective asymptotic line in agreement with the asymptotic behavior of the option prices.

Different models will have different predictions concerning the asymptotic slopes of implied variance curves. By studying a cross-section of option prices, one can determine the empirical validity of a given model by simply observing these slopes and comparing the observations to the predictions of a calibrated model. We take this approach in the following section to show the emprical validity of the Heston model.

EMPIRICAL OPTIONS DATA

In the previous section, we relied on simulated data to test the Heston model’s sensitivity to model parameters. In this section, we calibrate our model to options data for all LETFs and ILETFs listed in Table 1.

There are five parameters to calibrate: mean reversion rate κ, long-term variance θ, volatility of variance ε, correlation ρ and initial volatility v0. Since all the ETFs track the same underlying index, their underlying processes are related through the leverage factor ℓ. The five unknown parameters to be calibrated are therefore common to all members of the sextet.

We follow the most common approach in the option pricing calibration literature and minimize the difference between observed option prices and Heston model option prices:Footnote 18

with the weight function ωT, l. Since the call options values are proportional to the initial price L0ℓ for each ETF, we normalize the absolute difference of the market price and the model price by dividing by the initial LETF price. Other calibration approaches have been proposed according to the one-to-one relationship between the option price and the implied volatility. Instead of fitting the option prices directly, one could fit the model volatility/variance to the market volatility/variance implied by the Black-Scholes model in the least square sense (see Kjellin and Lövgren, 2006). For the current article, we discuss the optimization problem in equation (13) with equal weight ωT, l=1.

Using the procedure outlined above, we solved for the model parameters for over 100 trading days between July and December 2009. The best-fit parameters varied each day, but over 90 per cent of the days have a volatility of variance parameter (ɛ) in the range [0.5, 3.5] and a correlation parameter (ρ) in the range [−0.45,−0.75].

As an example, we again focus on the LETF option data as of 19 October 2009. The optimization procedure is implemented in MATLAB using the routine lsqnonlin. Most optimization procedures are very efficient and require less than 200 function evaluations.

Since in-the-money call options on negatively LETFs have higher prices than the same option on a positively LETFs, we expect the correlation between the asset price and variance to be negative. Indeed, our results indicate the best-fit value for the correlation is −0.565.

Since our model uses more options data (option data over a sextet of LETFs), the calibrated parameters are more precisely determined and stable when compared to a calibration using only options on the unleveraged member of the sextet (SPY, ℓ=1).

Given the calibrated model parameters in Table 5, we can compute the asymptotic behavior of the implied variance curves. The results of this computation are summarized in Table 6.

The difference between βR(ℓ) and βL(−ℓ) is more pronounced here than in Table 4 as a result of the volatility of variance ɛ. This calibrated parameter ɛ is more than 10 times larger than that used for the numerical simulations in the fourth section. We plot the implied variance curves of the market prices as well as the asymptotic implied variance lines in Figure 7 for SPXU (ℓ=−3) and UPRO (ℓ=+3).

The variance implied by the market prices of options on UPRO and SPXU are plotted in bold in Figure 7. The asymptotic behavior of these empirical curves is explained by the calibrated Heston model.

CONCLUSION

This article was motivated by the empirical observations of robust and persistent crooked smiles implied by the option prices on LETFs and ILETFs. In particular, we note that deep-in-the-money call options on the LETF with leverage number ℓ>0 are more expensive than call options with the same moneyness and expiration on the ILETF with leverage number −ℓ. Since the Black-Scholes model cannot properly explain this phenomena, we turn to the Heston stochastic volatility model. Since the call option price of Heston model is given explicitly, it is convenient to analyze the Heston model than other stochastic volatility model, which in general need Monte Carlo simulations. Following Lipton (2001), we derived the option values of LETFs and ILETFs with the same underlying via the Green’s function approach. Here we used one important fact that the dynamics of LETFs and ILETFs with the same underlying index have related dynamics.

We gathered pricing data for LETF options on the sextet of ETFs (ℓ∈{−3, −2, −1, 1, 2, 3}) with the S&P 500 as the underlying index. We showed that the Heston model can reproduce the crooked smiles observed in the empirical data and, using numerical simulations, showed how different phenomena in the options data could be produced with different model parameters. In particular, we studied the asymptotic behavior of Black-Scholes implied volatility curves and compared these to the predictions given by the Heston model calibrated to the market prices of options.

An important contribution of this article is that using options data of LETFs and ILETFs in addition to options data on the underlying index itself can better calibrate the pricing dynamics of the index. Using the closed-form solutions for the option prices of LETFs and ILETFs derived in this article, practitioners can more effectively and accurately determine the model parameters.

Notes

Other early empirical studies of implied volatilities include Latane and Rendleman (1976), Beckers (1981), Canina and Figlewski (1993) and Derman and Kani (1994).

For a review, see Hull (2011).

For a recent discussion of the detrimental effect of daily rebalancing in LETFs and ILETFs on buy-and-hold investors, see Dulaney et al (2012).

SPY has leverage factor of 1, and is actually unleveraged. In an abuse of terminology, we refer to SPY as an LETF with leverage factor ℓ=1.

In the current article, we assume the spot prices of both LEFT and ILEFT are identical, and set them as US$100. For empirical data, we use the concept of moneyness, defined as the ratio of the strike price to the spot price of the ETF (see also Lee, 2004). For consistency, we also normalize the option prices by the spot price of the ETF.

Both of these statements make the implicit assumption that the prices are being compared on options with the same moneyness and maturity.

The strike price at which the prices of call options on LETFs and ILETFs are equal is another common feature of the options data.

Derman and Kani (1994) discuss the connection between the dynamics of the underlying stock price – which determines the moments of the return distribution – and the volatility smile. The Heston model has been studied before as an explanation for volatility smiles present in the Black-Scholes model – see, for example, Sircar and Papanicolaou (1999).

When the correlation is 0, the Heston model is equivalent to the Black-Scholes model.

For simplicity, we drop the subscript t for the price process Lt.

For a constant volatility model, the realized variance is simply ∫0tvdt=vt. For a more complete discussion of this topic, see Avellaneda and Zhang (2010).

This change of variables is consistent with that given by Proposition 1 in Ahn et al (2012).

Andersen and Piterbarg (2007) have studied the time of moment explosion within the Heston model.

See Leung and Sircar (2012) for a recent study of implied volatility surfaces implied by the market prices of options on LETFs.

Here we use the notation x=log(K/F0) for the moneyness with respect to the stock’s forward price for contracts expiring T years from today.

Both of these statements rely on the implicit assumption that ρ<0.

For example, if the call option with strike K on the positively LETF with leverage number ℓ is more expensive than the call option with strike K on the negatively LETF with leverage number −ℓ when ρ>0 then, if ρ is changed to −ρ, the negatively leveraged option becomes more expensive.

For examples of other papers that have used this calibration procedure, see Bates (1996), Bakshi et al (1997), Carr et al (2003) and Schoutens et al (2004).

Again, for simplicity, we drop the subscript t for both Lt and vt.

Where

and

and  .

. denotes the complex conjugation of Z(τ, k, v).

denotes the complex conjugation of Z(τ, k, v).

References

Ahn, A., Haugh, M. and Jain, A. (2012) Consistent Pricing of Options on Leveraged ETFs. Working Paper.

Andersen, L. and Piterbarg, V. (2007) Moment explosions in stochastic volatility models. Finance and Stochastics 11 (1): 29–50.

Avellaneda, M. and Zhang, S. (2010) Path-dependence of leveraged ETF returns. SIAM Journal on Financial Mathematics 1 (1): 586–603.

Bakshi, G., Cao, C. and Chen, Z. (1997) Empirical performance of alternative option pricing models. Journal of Finance 52 (5): 2003–2049.

Bates, D. (1996) Jumps and stochastic volatility: Exchange rate process implicit in deutsche mark options. The Review of Financial Studies 9 (1): 69–107.

Beckers, S. (1981) Standard deviations implied in option prices as predictors of future stock price variability. Journal of Banking and Finance 5 (3): 363–382.

Benaim, S. and Friz, P. (2008) Smile asymptotics II: Models with known moment generating functions. Journal of Applied Probability 45 (1): 16–32.

Benaim, S. and Friz, P. (2009) Regular variation and smile asymptotics. Mathematical Finance 19 (1): 1–12.

Black, F. and Scholes, M. (1973) The pricing of options and corporate liabilities. Journal of Political Economy 81 (3): 637–654.

Canina, L. and Figlewski, S. (1993) The informational content of implied volatility. Review of Financial Studies 6 (3): 659–681.

Carr, P., German, H., Madan, D. and Yor, M. (2003) Stochastic volatility for lévy process. Mathematical Finance 13 (3): 345–382.

de Marco, S. and Martini, C. (2012) Term structure of implied volatility in symmetric models with applications to Heston. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance 15 (4): 1–27.

Derman, E. and Kani, I. (1994) The volatility smile and its implied tree. RISK 7 (2): 139–145.

Dulaney, T., Husson, T. and McCann, C. (2012) Leveraged, inverse and futures-based ETFs. PIABA Bar Journal 19 (1): 83–107.

Friz, P. and Keller-Ressel, M. (2009) Moment explosions in stochastic volatility models. In: R. Cont (ed.) Encyclopedia of Quantitative Finance. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 1247–1253.

Friz, P., Gerhold, S., Golisashvili, A. and Sturm, A. (2011) On refined volatility smile expansion in the Heston model. Quantitative Finance 11 (8): 1151–1164.

Heston, S. (1993) A closed-form solution for options with stochastic volatility with applications to bond and currency options. Review of Financial Studies 6 (2): 327–343.

Hull, J. (2011) Options, Futures and Other Derivatives. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Hull, J. and White, A. (1987) The pricing of options on assets with stochastic volatilities. Journal of Finance 42 (2): 281–300.

Jackwerth, J. and Rubinstein, M. (1996) Recovering probability distributions from option prices. Journal of Finance 51 (5): 1611–1631.

Kjellin, R. and Lövgren, G. (2006) Option pricing under stochastic volatility. Thesis, Göteborgs Universitet, Göteborg, Sweden.

Latane, H. and Rendleman, R. (1976) Standard deviation of stock price ratios implied in option prices. Journal of Finance 31 (2): 369–381.

Lee, R. (2004) Standard deviation of stock price ratios implied in option prices. Mathematical Finance 14 (3): 469–480.

Leung, T. and Sircar, R. (2012) Implied Volatility of Leveraged ETF Options. Working Paper.

Lipton, A. (2001) Mathematical Methods for Foreign Exchange: A Financial Engineer’s Approach. New Jersey: World Scientific.

Merton, R. (1976) Option pricing when underlying stock distributions are discontinuous. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 125–144.

Rollin, S. (2008) Spot Inversion in the Heston Model. Working Paper.

Rollin, S., Ferreiro-Castilla, A. and Utzet, F. (2009) A New Look at the Heston Characteristic Function. Working Paper.

Rubinstein, M. (1985) Nonparametric Tests of Alternative Option Pricing Models Using All Reported Trades and Quotes on the 30 Most Active CBOE Option Classes from August 23, 1976 to August 31, 1978. Journal of Finance 40(2): 455–480.

Rubinstein, M. (1994) Implied binomial trees. Journal of Finance 49 (3): 771–818.

Schoutens, W., Simons, E. and Tistaert, J. (2004) A Perfect Calibration! Now What? Wilmott Magazine, March, pp. 66–78.

Sircar, K. and Papanicolaou, G. (1999) Stochastic volatility, smile & asymtotics. Applied Mathematical Finance 6 (2): 107–145.

Zhang, J. (2010) Path-dependence properties of leveraged exchanged-traded funds: Compounding, volatility and option pricing. PhD thesis, NYU, New York, NY.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

3has extensive experience in securities class action litigation, financial analysis, investment management and valuation disputes. Prior to founding the Securities Litigation and Consulting Group, he was Director at LECG and Managing Director, Securities Litigation at KPMG. He was a senior financial economist at the Securities and Exchange Commission, where he focused on investment management issues and contributed financial analysis to numerous investigations involving alleged insider trading, securities fraud, personal trading abuses and broker–dealer misconduct. In addition, he is a CFA® charterholder.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Theorem 1

We follow Lipton (2001) for modeling and solving the call option prices on leverage ETFs. Choosing the risk premium  , we find that the option price C(L, v, τ) follows:Footnote 19

, we find that the option price C(L, v, τ) follows:Footnote 19

where τ=T−t is the time-to-maturity for the option,  is the new mean-reversion rate and

is the new mean-reversion rate and  new is mean-reversion variance level, respectively.Footnote 20 To simplify the equation above, we write the equation in terms of the forward price (F) and introduce

new is mean-reversion variance level, respectively.Footnote 20 To simplify the equation above, we write the equation in terms of the forward price (F) and introduce  , such that

, such that

Then the new variable satisfies the

We can write this equation in terms of dimensionless variables by introducing

Hence U(τ, X, v) satisfies

Equation (A.4) can be solved by introducing a Green’s function and applying the boundary condition relevant for the option at interest through the Spectral method (Lipton, 2001). In particular, the solution takes the form

where

The boundary condition of European call options is given by the payoff at maturity

In terms of dimensionless variables, this boundary condition can be written as

Since eX/2 is monotically increasing and e−X/2 is monotonically decreasing, it follows that eX/2−e−X/2⩾0 for all X⩾0. We change the order of integration in equation (A.5) to evaluate the X′ integral first. This integral takes the simple form given by

By evaluating the integral, we derive

In the last step we used the fact that  .Footnote 21 The value of a European call option in the Heston model is therefore given by equation (A.3). □

.Footnote 21 The value of a European call option in the Heston model is therefore given by equation (A.3). □

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, G., Dulaney, T., McCann, C. et al. Crooked volatility smiles: Evidence from leveraged and inverse ETF options. J Deriv Hedge Funds 19, 278–294 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2014.3

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jdhf.2014.3

and βR=limsupx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

and βR=limsupx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then and βL=lim supx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

and βL=lim supx→∞(σBS2(x))/(|x|/T), then

and

and  .

. denotes the complex conjugation of Z(τ, k, v).

denotes the complex conjugation of Z(τ, k, v).