Abstract

Can authoritarian leaders maintain support for their rule by providing private goods to selected individuals? Current theories disagree regarding this. While the selectorate theory argues that, in undemocratic regimes, leaders should provide private goods selectively to remain in office, civil war research suggests the opposite. Through a case study of the Slovak National Uprising, using both qualitative and quantitative evidence, this paper shows that the provision of private goods may fuel resentment against the regime and thus increase the risk of armed rebellion. This finding suggests that reliance on the selectorate theory may be fatal for regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Collier (2009) argues that today autocracies hold elections to keep up pretence of democracy, but frequently rig them. In some countries (such as Saudi Arabia), the selectorate is equal to the members of the royal family.

While Bueno de Mesquita et al. (2003) talk of a leader, we can of course assume that the same applies to political leadership in general (parties and regimes).

Humphreys and Weinstein (2008) provide excellent evidence that the reasons for mobilisation are not mutually exclusive.

All translations from Slovak have been made by the author.

There are three main reasons for this: (1) as a consequence of independence, Czechs were forced out of numerous positions in public administration and services, and these positions were filled by Slovak citizens; (2) as a consequence of the First Vienna Award, Slovakia lost much of its territory in the South to Hungary and in the North to Poland (although much less to the latter than to the former), cutting transport infrastructure connecting the country’s West to its East, which needed to be rebuilt; and (3) Slovak industry became a workhorse for the German war effort.

See Hallon (2007) for a brief overview of the legislation and Kamenec (1991) for the definitive historical account. Owing to missing data, the present paper does not deal with the dispossession of petty assets such as jewellery, cash or artworks that were seized by the government or were sold to the local population.

Whether or not the Slovak government knew about the fate of Jews in German concentration camps is a major topic of debate among the historians of the period. Nevertheless, this discussion is largely irrelevant for this paper and I shall not even approach it.

On the other hand, the regime never carried out a land reform which many had hoped for (Kamenec 2011).

On the resistance side. There are no readily available data about the losses of German and government forces.

In Figure 1, the borders of the districts do not represent exactly the borders of the districts at that time, as no map of the districts from that period is available. I have, therefore, created Thiessen polygons of individual territorial units (villages, towns, cities) and then dissolved the internal borders at the district level. This level of precision, I believe, is quite sufficient for the present purposes.

For a variety of reasons, the list includes those who died abroad, such as resistance members who fought abroad and those who were captured and killed in concentration camps for their activities and so on

Subsequent analysis is robust to a replacement of Roman Catholics with Protestants.

As opposed to those of Jewish nationality. Jews in the period stated frequently that their nationality was Hungarian, German or Slovak, even though ‘Jewish’ nationality could be selected (Klamková 2010b).

For robustness checks, I rerun all the models with a jackknife estimate of standard errors. The basic principle of jackknifing is that the full original sample is re-sampled systematically leaving out one observation every turn and then averaging out the results. All the results are confirmed in the robustness checks except for Models 2 and 4. This may simply be because of the small size of the sample, given that the general tendency is confirmed again in Models 2a and 4a, including in the jackknifed estimates. Furthermore, I re-run Models 1–4 without outliers (observations with leverage above 0.3 and Pearson residual above 2). All the main results hold. The results can be found in the online appendix.

For brevity, I do not report the odds ratios in this paper, but the respective tables are available in the online appendix.

As a reviewer pointed out rightly, Slovakia is a fairly small country and ‘we are not talking about the Congo’.

Although this support base was not equal to the HSĽS’s co-religionists or former voters.

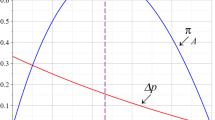

The effect is captured even better graphically in the Online Appendix Figure 1. Online Appendix Figure 2, based on Model 2a, shows the likelihood of the emergence of rebellion at varying strengths depending on the size of the local Jewish population before the war while keeping other variables at their means.

Ward (2002) reports that approximately 1,000 such exemptions were issued.

References

Aly, Götz (2005) Hitlers Volksstaat: Raub, Rassenkrieg und nationaler Sozialismus, Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer.

Berman, Eli, Jacob N. Shapiro and Joseph H. Felter (2011) ‘Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq’, Journal of Political Economy 119 (4): 766–819.

Blattman, Christopher and Edward Miguel (2010) ‘Civil War’, Journal of Economic Literature 48 (1): 3–57.

Boulding, Kenneth E. (1962) Conflict and Defense: A General Theory, New York: Harper.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce and Alastair Smith (2011) The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics, New York: PublicAffairs.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M Siverson and James D Morrow (2003) The Logic of Political Survival, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Buhaug, Halvard (2010) ‘Dude, Where’s My Conflict?: LSG, Relative Strength, and the Location of Civil War’, Conflict Management and Peace Science 27 (2): 107–28.

Buhaug, Halvard, Lars-Erik Cederman and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch (2014) ‘Square Pegs in Round Holes: Inequalities, Grievances, and Civil War’, International Studies Quarterly 58 (2): 418–31.

Buhaug, Halvard, Lars-Erik Cederman and Jan Ketil Rød (2008) ‘Disaggregating Ethno-Nationalist Civil Wars: A Dyadic Test of Exclusion Theory’, International Organization 62 (3): 531–51.

Buhaug, Halvard, Scott Gates and Päivi Lujala (2009) ‘Geography, Rebel Capability, and the Duration of Civil Conflict’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (4): 544–69.

Buhaug, Halvard, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, Helge Holtermann, Gudrun Østby and Andreas Forø Tollefsen (2011) ‘It’s the Local Economy, Stupid! Geographic Wealth Dispersion and Conflict Outbreak Location’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (5): 814–40.

Cambel, Samuel (1996) Slovenská dedina 1938–1944 [Slovak countryside 1938–1944], Bratislava: Slovak Academic Press.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, Halvard Buhaug and Jan Ketil Rød (2009) ‘Ethno-Nationalist Dyads and Civil War: A GIS-Based Analysis’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (4): 496–525.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, Andreas Wimmer and Brian Min (2010) ‘Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis’, World Politics 62 (1): 87–119.

Collier, Paul (2009) Wars, Guns and Votes: Democracy in Dangerous Places, London: Bodley Head.

Collier, Paul and Anke Hoeffler (1998) ‘On Economic Causes of Civil War’, Oxford Economic Papers 50 (4): 563–73.

Collier, Paul, Anke Hoeffler and Dominic Rohner (2009) ‘Beyond Greed and Grievance: Feasibility and Civil War’, Oxford Economic Papers 61 (1): 1–27.

Deák, Ladislav (2005) Viedenská arbitráž 2.november 1938. Dokumenty III. Rokovania (3.november 1938–4.apríl 1939) [First Vienna Award of 2 November, 1938. Documents III. Sessions (3 November, 1938–4 April, 1939)] Martin: Matica Slovenská.

Fearon, James D. (1995) ‘Rationalist Explanations for War’, International Organization 49 (3): 379–414.

Fearon, James D (2011) ‘Governance and Civil War Onset’, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9123 (accessed 12 July, 2015).

Fearon, James D. and David D. Laitin (2003) ‘Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War’, American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75–90.

Fjelde, Hanne (2010) ‘Generals, Dictators, and Kings: Authoritarian Regimes and Civil Conflict, 1973–2004’, Conflict Management and Peace Science 27 (3): 195–218.

Gurr, Ted Robert (1970) Why Men Rebel, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hallon, Ľudovít (2007) ‘Arizácia na Slovensku 1939–1945 [Aryanisations in Slovakia 1939–1945]’, Acta Oeconomica Pragensia 15 (7): 148–60.

Hegre, Håvard and Nicholas Sambanis (2006) ‘Sensitivity Analysis of Empirical Results on Civil War Onset’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 50 (4): 508–35.

Horowitz, Donald L (2000) Ethnic Groups in Conflict, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Humphreys, Macartan and Jeremy M. Weinstein (2008) ‘Who Fights? The Determinants of Participation in Civil War’, American Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 436–55.

Jablonický, Jozef and Jozef Pivovarči (1961) The Slovak National Uprising, Bratislava: Obzor.

Josko, Anna (1973) ‘The Slovak Resistance Movement’, in Victor S. Mamatey and Radomír Luza, eds, A History of the Czechoslovak Republic, 1918–1948, 362–83, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kalyvas, Stathis N. (2006) The Logic of Violence in Civil War, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kamenec, Ivan (1991) Po stopách tragédie [On the Trail of Tragedy], Bratislava: Archa.

Kamenec, Ivan (2011) ‘The Slovak state, 1939–1945’, in Dušan Kováč, Mikuláš Teich and Martin D Brow, eds, Slovakia in History, 175–92, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keefer, Philip (2008) ‘Insurgency and Credible Commitment in Autocracies and Democracies’, World Bank Economic Review 22 (1): 33–61.

Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (1995) A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Klamková, Hana (2010a) ‘Nálady a postoje slovenského obyvateľstva k tzv. židovskej otázke po potlačení Slovenského národného povstania, 1944–1945 [Moods and Attitudes of the population of Slovakia towards the so-called Jewish question after the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising, 1944–1945]’, Acta Universitatis Carolinae, Studia Territorialia 10 (2): 69–93.

Klamková, Hana (2010b) ‘Nepokradneš! Nálady a postoje slovenskej spoločnosti k tzv. židovskej otázke, 1938–1945’ [Thou shall not steal! Moods and Attitudes of the Slovak society towards the so-called Jewish question, 1938–1945], unpublished PhD dissertation, Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Social Sciences, Institute of International Studies.

Kolektív Autorov Múzea SNP [Collective of Authors of the Museum of the SNU ] (n.a.) ‘Ľudské straty a obete na Slovensku v rokoch 2.sv. vojny’ [Human losses and victims of the Second World War in Slovakia], unpublished, Banská Bystrica: Múzeum SNP.

Kováč, Dušan (2010) Dejiny Slovenska [A History of Slovakia], Prague: Nakladatelství Lidové Noviny.

Krivý, Vladimír (2012) ‘Electronic Database of Parliamentary Elections Results in all Slovak Municipalities From 1929’, http://sasd.sav.sk/en/data_katalog_abs.php?id=sasd_2010001 (accessed 12 July, 2015).

Krivý, Vladimír, Viera Feglová and Daniel Balko (1996) Slovensko a jeho regióny: sociokultúrne súvislosti volebného správania [Slovakia and its Regions: Sociocultural Context of Electoral Behavior], Bratislava: Nadácia Médiá.

Kubátová, Hana (2010) ‘Popular Responses to the Plunder of Jewish Property in Wartime Slovakia’, CEU Yearbook of Jewish History 7: 109–26.

Lacko, Martin (2008) Slovenské národné povstanie 1944 [The Slovak National Uprising 1944], Bratislava: Slovart.

Lipscher, Ladislav. (1992) Žídia v slovenskom štáte, 1939–1945 [Jews in the Slovak Republic, 1939–1945], Bratislava: Print-service.

Lowe, Keith. (2012) Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Marks, Gary. (2012) ‘Europe and Its Empires: From Rome to the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (1): 1–20.

Mousseau, Michael. (2003) ‘The Nexus of Market Society, Liberal Preferences, and Democratic Peace: Interdisciplinary Theory and Evidence’, International Studies Quarterly 47 (4): 483–510.

Østby, Gudrun, Ragnhild Nordås and Jan Ketil Rød (2009) ‘Regional Inequalities and Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa’, International Studies Quarterly 53 (2): 301–24.

Paige, Jeffery M. (1975) Agrarian Revolution: Social Movements and Export Agriculture in the Underdeveloped World, New York: Free Press.

Podolec, Ondrej (2004) ‘‘Ticho pred búrkou (Sonda do nálad slovenskej spoločnosti na jar 1944)’ [The Calm Before the Storm (An Enquiry into the Moods of Slovak Society in Spring 1944)]’, in Martin Lacko, ed., Slovenská republika 1939–1945 očami mladých historikov III: Povstanie roku 1944 [Slovak Republic 1939–1945 Through the Young historians’ eyes, Vol III: The 1944 Uprising], 19–33, Trnava: Katedra histórie Filozofickej fakulty Univerzity sv.Cyrila a Metoda.

Prečan, Vilém. (2011) ‘The Slovak National Uprising: The Most Dramatic Moment in the Nation’s History’, in Dušan Kováč, Mikuláš Teich and Martin D. Brown, eds, Slovakia in History, 206–28, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Regan, Patrick M. and Daniel Norton (2005) ‘Greed, Grievance, and Mobilization in Civil Wars’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 49 (3): 319–36.

Scott, James C. (1985) Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Senčák, Michal, ed. (1947) Štatistická príručka Slovenska 1947 [Statistical Handbook of Slovakia 1947], Bratislava: Štátny plánovací a štatistický úrad.

Shirk, Susan L. (1993) The Political Logic of Economic Reform in China, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Šišjaková, Jana (2008) ‘Protižidovské nepokoje po druhej svetovej vojne – rok 1945 na východnom Slovensku’ [Anti-Jewish riots after World War II – East Slovakia in 1945], Človek a spoločnosť 2, http://www.saske.sk/cas/archiv/2-2008/03-Sisjakova.html (accessed14 July, 2015).

Státní úrad statistický [The State Bureau of Statistics] (1934) Sčítaní lidu v Republice Československé ze dne 1.prosince 1930. Díl I. [The Census in the Czechoslovak Republic of December 1, 1930. Part I], Prague: Bursík & Kohout.

Themnér, Lotta and Peter Wallensteen (2013) ‘Armed Conflicts, 1946–2012’, Journal of Peace Research 50 (4): 509–21.

Urdal, Henrik (2005) ‘People vs. Malthus: Population Pressure, Environmental Degradation, and Armed Conflict Revisited’, Journal of Peace Research 42 (4): 417–34.

Ústav pamäti národa [National Memory Institute] (2008) ‘Arizácie podnikov Židov’ [Aryanisation of the Jewish Businesses], http://www.upn.gov.sk/arizacie/ (accessed 12 July, 2015).

Ústavný zákon zo dňa 21. júla 1939 o Ústave Slovenskej republiky [Constitutional Law of 21 July 1939 on Constitution of the Slovak Republic], http://www.upn.gov.sk/data/pdf/ustava1939.pdf (accessed 12 July, 2015).

Wagner, R. Harrison. (2000) ‘Bargaining and War’, American Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 469–84.

Walter, Barbara F. (2004) ‘Does Conflict Beget Conflict? Explaining Recurring Civil War’, Journal of Peace Research 41 (3): 371–88.

Ward, James Mace. (2002) ‘“People Who Deserve It”: Jozef Tiso and the Presidential Exemption’, Nationalities Papers 30 (4): 571–601.

Weidmann, Nils B., Jan Ketil Rød and Lars-Erik Cederman (2010) ‘Representing Ethnic Groups in Space: A New Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research 47 (4): 491–99.

Wimmer, Andreas, Lars-Erik Cederman and Brian Min (2009) ‘Ethnic Politics and Armed Conflict: A Configurational Analysis of a New Global Data Set’, American Sociological Review 74 (2): 316–37.

Wucherpfennig, Julian, Nils B. Weidmann, Luc Girardin, Lars-Erik Cederman and Andreas Wimmer (2011) ‘Politically Relevant Ethnic Groups Across Space and Time: Introducing the GeoEPR Dataset’, Conflict Management and Peace Science 28 (5): 423–37.

Zhukov, Yuri (2007) ‘Examining the Authoritarian Model of Counter-Insurgency: The Soviet Campaign Against the Ukrainian Insurgent Army’, Small Wars & Insurgencies 18 (3): 439–66.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Vratko Strmeň, Martina Gonosová and Gabriela Onderčová for assistance in data collection. The author is thankful to the Museum of the Slovak National Uprising in Banská Bystrica for generously sharing their casualty data. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Research in Security and Conflict colloquium at the University of Amsterdam and at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The author would also like to thank the attendees at these meetings, the three excellent JIRD reviewers, as well as Scott Abramson, Hana Kubátová, Gary Marks, Andrea Ruggeri, Jeremiah Trinidad-Christensen, Andrej Tušičišny, Wolfgang Wagner and James Ward for excellent advice on the earlier drafts of the paper. Alyson Price and David Frank Barnes proofread the paper with much care. The EUI library could not have been more helpful in tracking down literature sources from libraries all over Europe. All mistakes remain my own. Replication package and online appendix are available from the author’s website http://www.mwpweb.eu/MichalOnderco/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Onderco, M. The provision of private goods and the emergence of armed rebellion: the case of the Slovak National Uprising 1944–1945. J Int Relat Dev 19, 76–100 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2015.30

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jird.2015.30