Abstract

A well-articulated institutional health research agenda can assist essential contributors and intended beneficiaries to visualize the link between research and community health needs, systems outcomes, and national development. In 2011, Tanzania's Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) published a university-wide research agenda. In developing the agenda, MUHAS leadership drew on research expertise in its five health professional schools and two institutes, its own research relevant documents, national development priorities, and published literature. We describe the process the university underwent to form the agenda and present its content. We assess MUHAS's research strengths and targets for new development by analyzing faculty publications over a five-year period before setting the agenda. We discuss implementation challenges and lessons for improving the process when updating the agenda. We intend that our description of this agenda-setting process will be useful to other institutions embarking on similar efforts to align research activities and funding with national priorities to improve health and development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1990, the Commission on Health Research for Development described the inadequacy of funds allocated to research to address the disease burdens suffered by people living in low- and middle-income countries.1 Although the situation has changed, with greater funding and changing patterns of poverty and disease, promoters of health research for development emphasize that ‘health research applied to the needs of low- and middle-income countries remains grossly under resourced in many areas’.2 One reason for this imbalance is that institutions in countries with high disease burdens rarely articulate their research priorities to research partners and funders.

The Council on Health Research for Development, the Global Forum for Health Research, and the World Health Organization (WHO) lead efforts to set national and regional research priorities and agendas, and to build system capacity for research to address these population health needs.3, 4, 5, 6 Unlike dedicated research organizations, it is unusual for a university to set an institutional research agenda – the variety of faculty interests, the spread of expertise across schools and departments, and unevenness in access to much-needed funding can make this difficult. In Tanzania, with a staggering burden of disease and very scarce research resources, an institutional agenda offers the possibility of more discipline in shaping research and collaboration to improve health.

In 2007, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) left the University of Dar es Salaam to become an autonomous university. Its leadership began to strengthen its administrative infrastructure to support first-class education and research. The Directorate of Research and Publications (DRP) set out to establish the institution's research agenda and to review procedures for supporting faculty research. MUHAS intended the new agenda to provide critical direction, tying together institutional research priorities and activities with the other responsibilities of academic staff: teaching and community service activities.7 Importantly, this agenda was to harness the expertise of faculty in all its professional schools and institutes.

We describe the deliberative process of formulating the first, comprehensive research agenda for MUHAS aimed at addressing national priorities, and present the proposed research themes. We then review MUHAS's research strengths and targets for developing new research capacity by categorizing 5 years of MUHAS's research output in relation to the themes. Finally, we discuss implementation challenges and lessons learned, and lay out next steps.

MUHAS's Objectives in Developing a Research Agenda

Tanzania is on track to meet some of the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including targets on child and infant mortality, while it is likely to fall short of many targets, especially for maternal mortality.8 According to estimates made by the WHO in 2004, the leading causes of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost in Tanzania were: HIV/AIDS (accounting for 18 per cent of all DALYs lost), negative maternal and perinatal outcomes (14 per cent), tuberculosis and respiratory infections (13 per cent), malaria (9 per cent), injuries (8 per cent), diarrheal disease (6 per cent), neuropsychiatric conditions (5 per cent), nutritional diseases (4 per cent), and cardiovascular diseases (4 per cent).9 Not only must Tanzania's health researchers collect essential information to update these estimates, but they must also inform the government about how to reduce and prevent the disease burden with timely diagnosis and treatment and through better access to primary health care.

Some 300 MUHAS faculty in its schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and public health and social science and its institutes of allied health sciences and traditional medicine undertake research.10 Like most universities, MUHAS's institutional research portfolio reflects its faculty composition, their interests and those of collaborators, and the availability of funding. But MUHAS leadership has strongly encouraged researchers to concentrate on studies aimed at improving the health and well-being of Tanzanians. As part of the University of Dar es Salaam, these health sciences faculty first identified institutional priority areas for research in 1995 and updated them in 2004. In forming its first agenda as an autonomous university, MUHAS intended research to align more closely with development targets in national policy documents. MUHAS recognized that some themes from 2004 would remain priorities but that others would give way to emerging problems, for example, non-communicable diseases.11 Importantly, MUHAS wanted its researchers to generate and then champion priorities in renewing the agenda.

The Deputy Vice Chancellor for Academic, Research and Consultancy Services appointed a Task Team to draft the agenda, consisting of the Director (as Chair) and Deputy Director for Research, and three senior researchers (Authors JM, MA, MM, FM, and AK), and instructed them to hold university-wide consultations. The Task Team gathered and reviewed internal and national documents, and reviewed methods for priority setting at the national level and agendas from the few institutions in other countries that had published their processes or results,5, 12, 13 and benefitted from the work of Cioffi et al14 and the Delphi process as described by Wright.15

Two national documents and one set of United Nations priorities guided the Task Team: the Tanzania Vision 2025,16 the National Strategy for Growth and Poverty Reduction,17 and MDGs.18 These documents target broad development goals: for example, to halve the proportion of people living below the poverty line, halt and reverse the spread of HIV, improve child nutrition, and promote maternal health.

Development of the MUHAS Research Agenda

The Task Team started its consultations by asking deans and directors for unit research agendas. The response was poor, so the team sent a questionnaire to 67 principal investigators registered with the DRP asking them to summarize: previous and ongoing research projects; knowledge gaps requiring further research; priority areas for generating new knowledge; and the capacity of the current study teams to undertake research in areas consistent with national priorities. The questionnaire also asked respondents to list available research equipment and other resources. Ten principal investigators responded. The team then invited all 67 principal investigators to a 1-day workshop to present the same information; 15 attended (including some who had already answered the written questionnaire). Despite the disappointing turnout, discussions proved informative about topic areas, methods, results, equipment (facilities and other resources), along with principal investigators’ views of gaps and priorities. Presentations and comments generated lively discussions moving the process toward consensus on priority topics. The Task Team then collected all documentation (literature review materials, completed questionnaires, information recorded during the 1-day workshop) and retreated for 3 days of intensive analysis and drafting. The team circulated a draft of themes and subthemes to schools and directorates for comments. Although the response rate was low, the team considered this sufficient as issues raised in the responses were largely consistent; the Task Team finally formed the agenda around 10 themes with subthemes. MUHAS's Committee of Deans and Directors reviewed the document, asked for revisions, and sent it for final approval by the university's highest governing body, the council. MUHAS published this first full institutional research agenda in October 2011, and launched it officially in December 2011.

The 2011 Research Agenda

The Task Team's greatest challenge was to incorporate apparently disparate priority areas into a manageable number of themes. They then found a way to bring together previously unconnected elements of basic and clinical research, also including drug discovery, formulation, and development within one theme. For example, because a focus on malaria was common among researchers in child health, reproductive health, traditional medicine, public health, and pharmacy, it was possible to consolidate all these perspectives into subthemes under malaria, covering: pathogenesis and immunology of malaria; severe malaria in children and pregnant women, and associated factors; chemotherapy of malaria and genetics of antimalarial resistance; antimalarial drug blood levels and pharmacogenetics in different groups; malaria vaccine development and evaluation in children; and malaria vector control, including use of natural products. A similar process of sorting and merging yielded eight themes covering much of the terrain of interest promoted by participants in the process.

The Task Team debated the content of the grouping for non-communicable diseases, and agreed to make it expansive, including: cancers, mental health, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and occupational health. The team discussed where to place nutrition as it was relevant to child health, non-communicable diseases, and HIV and AIDS, and eventually reached agreement to place it under non-communicable diseases. On the basis of feedback from circulation of the draft agenda to faculty members, the Task Team added neglected tropical diseases as an independent theme. To reflect university-wide interest in introducing educational innovations in the ongoing curricular revision,19 the Task Team added a further stand-alone theme to stimulate research about health professions education – thus assembling 10 themes.

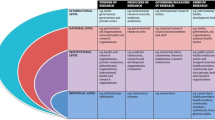

Table 1 describes the 10 themes that form the new agenda. Because the agenda does not rank themes by relative importance for addressing Tanzania's health priorities, we also provide in Table 1 an indication of the distribution of Tanzania's 2004 burden of disease across these themes.9

Observations from Past Research

We wanted to better understand MUHAS researchers’ previous activities in areas designated as priority themes – as the foundation for future contributions. Thus, we reviewed papers published by MUHAS faculty listed in the 2008–2009 MUHAS prospectus in the 5-year period before the start of agenda setting. We identified and downloaded into an Excel file 537 papers published by 143 faculty between 2005 and 2009, in journals registered with PubMed20 (the appendix describes our methodology). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of these papers across the 10 themes of the research agenda. It is important to note that by working from PubMed our search excluded publications in some Tanzanian or other journals from the region that may be particularly influential in shaping local policies and practice.

Distribution of 537 papers registered in PubMed20, 2005–2009, by MUHAS 2011 research themes, and by the school or institute in which the primary MUHAS author was appointed.

Our major observations of this research published by MUHAS faculty before the development of the agenda are:

-

1)

The largest concentration of publications fell in the HIV/AIDS theme (159 papers representing 30 per cent of the total), reflecting both the high disease burden of HIV/AIDS in Tanzania (estimated to be 18 per cent of all DALYs lost in 20049) and the availability of funding through partner institutions. Papers in this theme brought in a secondary focus on other themes including: malaria, tuberculosis, child health, reproductive health, non-communicable diseases (cancers, mental health, nutrition), and health systems research.

-

2)

Twelve per cent of papers described non-communicable diseases: three of these papers related to cardiovascular disease, and three described non-HIV related cancers in Tanzania.

-

3)

Health systems research was poorly represented despite significant challenges to the Tanzanian health system. Only 13 papers fell within this category.

-

4)

Three of the current themes had generated little previous attention by MUHAS authors: injuries (eight papers), neglected tropical diseases (five papers), and health professions education (six papers).

-

5)

Twenty-eight per cent (151) of the papers fell outside the 10 new themes. Approximately 26 per cent of such papers we categorized as dentistry; 25 per cent as basic science, with prominent fields being pharmacy, anatomy, molecular biology, immunology, and microbiology; and 19 per cent as traditional medicine.

-

6)

Authors from across the schools and institutes contributed to all themes, as the Task Team had concluded, for example, every school and institute published on HIV/AIDS, involving authors in 24 departments. Among papers with more than one MUHAS author, 16 departments were represented. At least five schools or institutes contributed to research on malaria, NCDs, child health, and reproductive health.

-

7)

MUHAS authors collaborated with researchers from other institutions. The average number of authors per paper was 6.7 with MUHAS faculty comprising 23.3 per cent of 3598 total authorships listed on the 537 papers. A MUHAS faculty member appeared as first author on 192, second author on 163, and last author (if not first or second) on 64 papers.

Launch and Early Implementation

On 8 December 2011, MUHAS officially launched the research agenda21 and distributed copies to MUHAS faculty, local and international colleagues, and ministry officials at the MUHAS Research Dissemination Day celebrating the nation’s 50 years of independence.

The DRP is working to address a number of issues to support implementation of the agenda:

-

1

Research infrastructure: A 2010 consultation with MUHAS researchers and administrators organized by the DRP highlighted the need to strengthen pre- and post-award support for faculty and students to implement the agenda. Thus DRP is forming three units: a Research Development Unit to assist faculty and students with grant applications; a Grants Management Unit to manage grants and ensure fiscal and academic accountability to donors; and an Institutional Review Board Unit to oversee research integrity and adherence to ethical standards. Although MUHAS has begun to appoint additional staff to carry out these activities, resource constraints limit the scope of this work.

-

2

Financial and human resources: Research at MUHAS is largely funded by international donors. A recent commitment by the government to allocate 1 per cent of its budget to support research may address some of the shortfall. But realization of the research agenda using all the available talent at MUHAS awaits the test of time. Depending on the availability of funds, the DRP will allocate internal small research grants to encourage researchers to focus on new research areas within the agenda. Implementation will also require MUHAS to recruit adequate numbers of well-trained administrative staff for the DRP, and to find funds to support grant seeking, innovation, and protection of intellectual property rights – activities that may not draw support from the wider donor community.

-

3

Research facilities: Given financial constraints in Tanzania, providing laboratory space for each researcher and her/his students is difficult. MUHAS needs to make arrangements for scientists to share laboratories, train staff for maintenance of laboratory equipment, avoid unnecessary duplication in procurement, and ensure appropriate care of expensive instruments. The MUHAS animal facility needs improvement and adequately trained staff to conduct ethically sound research.

-

4

Monitoring and reinforcing the agenda: The DRP is alerting MUHAS staff, students, collaborators, and funding agents to the centrality and elements of the new research agenda. This is so that departments, schools, or institutes incorporate aspects of the agenda in their strategic plans. The DRP maintains a database of faculty and student publications and will monitor these annually by themes. Describing the published work in the annual university research bulletins will allow management and faculty to monitor and step up implementation efforts as needed. The DRP will also devise ways to monitor and encourage updating of the research agenda, realigning the agenda annually to prevailing disease patterns and national health goals. The 2011 MUHAS Research Dissemination Day proved to be a useful first step.

Lessons and Aspirations

The main lesson is that the generation, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of the research agenda must be: (i) linked to the institution's strategic planning process, and (ii) aligned with national health challenges and goals. Research output (publications), researchers’ engagement with potential end users, and contributions to policy and practice will be crucial markers of success. For other research universities that may be planning institutional research agendas, the MUHAS process may also provide practical guidance lacking in the literature when the Task Team began its work. Other lessons learned include:

-

1

Engaging researchers: It was rewarding to have MUHAS scientists arguing for priorities on the basis of what they know, challenged by fellow scientists, until a priority list emerged; the open and constructive process of debate represented value for research planning in and of itself, and increased ownership of the agenda among MUHAS researchers. Even though participation was low, such open debate had not been common on the MUHAS campus. Delays by researchers and unfruitful follow-ups troubled the return of self-administered questionnaires, perhaps because busy researchers could not anticipate the benefits of taking time to complete the forms. The Task Team sent the instrument to principal investigators in order that they would consult members of their research teams about priority areas as they completed it. Perhaps next time it would be better to invite participants to a supervised questionnaire survey session to increase the response rate, and refer to the research agenda to demonstrate why the exercise is important.

-

2

Forming the agenda: The Task Team struggled with grouping research into a manageable number of themes, reflecting national priorities while engaging researchers’ capabilities and interests. The 10 themes contain some areas of institutional strength, some areas into which MUHAS needs to grow, and omits others where the strengths do not help to address national priorities. Some faculty criticize the agenda for stretching to cover all national priority areas and doing so without priorities among themes; others criticize the omission of specific research areas that are important strengths at MUHAS, for example in dentistry and traditional medicine, that have no stand-alone themes or subthemes.

-

3

Monitoring the implementation of the agenda: We found analysis of publications useful for assessing MUHAS's past strengths for furthering the agenda, and areas where the agenda's foundation was not robust. It is important for MUHAS to recognize at the start of implementation how few papers, published during the 5 years reviewed, addressed injuries, neglected tropical diseases, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, health services research, and health professions education. The methodology described in the appendix could be streamlined and used to assess the relative contributions of the institution's research to its priorities into the future. Inclusion of journals important for Tanzania's health system and practitioners that do not appear in PubMed will be important. Makerere University College of Health Sciences undertook a similar analysis of its publications and found this useful in understanding the extent to which its research output aligned with Ugandan health priorities.22

-

4

Monitoring policy, practice, and health impact: In addition to publications, MUHAS also needs a way to document and monitor its research contributions to strengthening national policy and health system operations. And the institution needs to continue learning how to increase research output to improve health and development – ultimately to understand how MUHAS's research contributes to the health and well-being of Tanzanians.

-

5

Encouraging creativity: Creativity and motivation, across schools and fields, are two essential assets of a vibrant university. It will be important to devise incentives for researchers to contribute to meeting national priorities, and to avoid discouraging additional research interests faculty may choose to pursue outside the priority list. Research categorized as ‘other’ mainly focused on the basic sciences that provide crucial training for postgraduate students and junior faculty. Such research can also form the basis for research in the priority areas.

Conclusion

Developing a research agenda is not simply a matter of assembling research topics, but a comprehensive process that must be ‘owned’ by the institution's researchers and top management – linked to a desire to achieve excellence. The process requires the university research community to internalize the research priorities into their broader strategic planning. We hope that documenting the prioritization process and early implementation of the new agenda at MUHAS will encourage other universities to share and compare their experiences.

References

Evans, J.R. (1990) Essential national health research. New England Journal of Medicine 323 (13): 913–915.

Matlin, S., Burke, M.A. and de Francisco, A. (eds.) (2007) Monitoring Financial Flows for Health Research 2007: Behind the Global Numbers. Switzerland: Global Forum for Health Research.

D'Souza, C. and Sadana, R. (2006) Why do case studies on national health research systems matter? Identifying common challenges in low-and middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine 62 (8): 2072–2078.

Kirigia, J.M. and Wambebe, C. (2006) Status of national health research systems in ten countries of the WHO African Region. BMC Health Services Research 6 (1): 135.

Nuyens, Y. (2007) Setting priorities for health research: Lessons from low-and middle-income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85 (4): 319–321.

Lansang, M.A. and Dennis, R. (2004) Building capacity in health research in the developing world. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82 (10): 764–770.

Chatterton, P. and Goddard, J. (2000) The response of higher education institutions to regional needs. European Journal of Education 35 (4): 475–496.

United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. (2008) Millennium Development Goals Report: Mid-Way Evaluation: 2000–2008. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, http://www.tz.undp.org/docs/mdgprogressreport.pdf, accessed 20 September 2012.

World Health Organization. (2004) The global burden of disease: 2004 update, http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/index.html, accessed 2 September 2012.

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. (2011) Prospectus 2011–2013. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, http://www.muchs.ac.tz/index.php/prospectus, accessed 20 September 2012.

Unwin, N. et al (2001) Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: Where do they feature in the health research agenda? Bulletin of the World health Organization 79 (10): 947–953.

Tomlinson, M., Chopra, M., Hoosain, N. and Rudan, I. (2011) A review of selected research priority setting processes at national level in low and middle income countries: Towards fair and legitimate priority setting. Health Research Policy and Systems 9 (15): 19.

Council on Health Research for Development. (2011) Priority setting in research for health: A management process for countries, http://www.cohred.org/prioritysetting/, accessed 20 September 2012.

Cioffi, J.P., Lichtveld, M.Y. and Tilson, H. (2004) A research agenda for public health workforce development. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 10 (3): 186.

Wright, T. (2007) Higher education for sustainability developing a comprehensive research agenda. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 1 (1): 101–106.

United Republic of Tanzania, Planning Commission. (1995) The Tanzania Development Vision 2025, http://www.tanzania.go.tz/vision.htm, accessed 20 September 2012.

United Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. (2010) National Strategy for the Growth and Reduction of Poverty II. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs, http://www.tz.undp.org/docs/MKUKUTA.pdf, accessed 20 September 2012.

United Nations, Office of the Secretary General. (2001) Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration, http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan004152.pdf, accessed 20 September 2012.

Ngassapa, O.D. et al (2012) Curricular transformation of health professions education in Tanzania: The process at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (2008–2011). Journal of Public Health Policy 33 (S1): S64–S91.

PubMed Health. (2012) PubMed Health, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/, accessed 12 July 2012.

Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences. (2011) Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Research Agenda. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, http://www.muhas.ac.tz/drpweb/dmdocuments/Research%20Agenda.pdf, accessed 20 September 2012.

Nankinga, Z. et al An assessment of Makerere University College of Health Sciences: Optimizing health research capacity to meet Uganda's priorities. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11 (Suppl 1): S12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

In 2011, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences published a university-wide research agenda. The authors explain the process, as it represented a major institutional advance for analyzing research strengths and areas for capacity building, while targeting research talent to national priorities.

Appendix

Appendix

Methodology for Analyzing MUHAS Publications Reported in PubMed

Paper selection: We took faculty names listed in the MUHAS 2008–2009 prospectus and searched for papers with these names as authors reported by PubMed20, published between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2009. We downloaded into Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) the full PubMed descriptors for each paper, including paper title, authors, affiliations, MeSH terms, journal title, place of publication, and abstract. We checked for and eliminated authors with similar names to MUHAS faculty but who were not from MUHAS (if their papers did not fall in the area of specialization of the MUHAS faculty with the same name, and there was no mention of Tanzania or MUHAS in the affiliation, title, abstract, or MeSH terms). We associated with each author, their school, and department. When there was more than one MUHAS author, we used the foremost MUHAS author to determine the school of origin of the paper.

Categorization of papers into MUHAS themes: After some preparation and piloting, one reviewer assessed the paper title (and abstract if needed) and determined whether its major focus fit into one of the 10 themes. If a paper's title or abstract did not indicate relevance to one of the themes, the reviewer categorized it as ‘other’. Papers classified as other were further classified into either: allergies, basic sciences, dentistry, infectious disease, public health, pulmonology, radiology, social science, STDs (non-HIV), surgery, traditional medicine, or other. The reviewer was instructed to be generous with allocation to the main themes; for example, a paper concerning opportunistic infections of HIV patients would be categorized under ‘HIV’ not ‘other: infectious disease’.

Limitations of the method: We might have omitted some papers published by MUHAS authors if they used different initials to those that appeared in the prospectus. Some miscategorization undoubtedly occurred, and many papers were difficult to categorize as their focus, results, and methods pulled from a variety of disciplines. As the search included only papers published in PubMed, it excluded publications in journals not registered with PubMed, including some Tanzanian and regional publications.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masalu, J., Aboud, M., Moshi, M. et al. An institutional research agenda: Focusing university expertise in Tanzania on national health priorities. J Public Health Pol 33 (Suppl 1), S186–S201 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2012.50

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2012.50