Abstract

Elected national representatives make decisions to fund health programmes, but may lack skills to interpret evidence on health-related topics. In 2011, we surveyed the 61 members of Botswana’s Parliament about their use of epidemiological evidence, then provided two half-days of training about using evidence. We included the importance of counter-factual evidence, the number needed to treat, and unit costs of interventions. A further session in 2012 covered evidence about the HIV epidemic in Botswana and planning the best mix of interventions to reduce new HIV infections. The 27 respondents reported they lacked good quality, timely evidence, and had difficulty interpreting and using evidence. Thirty-six, including seven ministers, attended one or both trainings. They participated actively and their evaluation was positive. Our experience in Botswana could potentially be extended to other countries in the region to support evidence-based efforts to tackle the HIV epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A growing literature discusses the need to translate knowledge from epidemiological and other research into action, and the methods for achieving this transfer.1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Although not without its critics,6 medical practice has seen a massive growth of evidence-based medicine.7, 8, 9 Now there are calls to use this approach in public health and health systems management.10 Some researchers present their findings to be accessible and to support informed decision making. Others rely on knowledge syntheses and systematic reviews to make their work useful for policy. More and more systematic reviews,11 have been generated, making available unprecedented quantities of evidence. With few unbiased filters to sift through it,12 policymakers and planners need to know more about how to use evidence that comes their way.

Part of the problem is the uneven mix of evidence from different sources. Much of the evidence does not come from systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or even a single RCT. Protagonists of a particular viewpoint can present a single strand of evidence, ignoring other strands. Knowledgeable decision makers, with some ability to sift through highlights and to ask the right questions about evidence, would be an important safeguard. Many decision makers lack these skills.13, 14 A 2012 international forum on evidence-informed health policymaking in low- and middle-income countries called for building the capacity of potential research users to evaluate and use research evidence.15

Initiatives have attempted to build health policymakers’ and planners’ capacity to use evidence in both rich and resource-poor settings.16, 17 These initiatives mostly target government technical officers, senior civil servants, and other advisers, on the assumption that they are then better able to advise elected representatives who make decisions about health funding. Programmes to train elected representatives have focused primarily on debating, law making, ethics, and the like.18, 19, 20 and 21 We have not found any reports of training elected representatives in the interpretation and use of health, or other, evidence.

HIV prevalence in Botswana is among the highest in the world.22 Tackling the epidemic is a national public health priority. In 2011, after some ill-informed debate in Parliament, the ruling party withdrew a revised national AIDS policy for further revision. The minimum education required for members of Parliament in Botswana is 7 years of schooling; current members all have at least school leaving certificates (12 years), and many have university degrees. To support more informed parliamentary debate on HIV and other issues, the minister for Presidential Affairs and Public Administration arranged training for members of Parliament. It covered interpretation and use of evidence to support decision making, particularly in the health field. We describe this training in evidence-based policymaking.

Methods

Survey of elected representatives

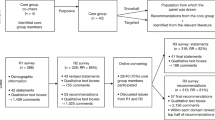

In October 2011, the Office of the National Assembly invited all 57 elected national representatives (and four appointed members of Parliament) to attend training over 2 days just before the opening of the parliamentary session. This office also provided us with a list of representatives with their contact numbers. During the 2 weeks before the training, we attempted to contact and interview as many of them as possible. Contacting the elected representatives required repeated phone calls (often to contact numbers not originally listed). The interviewer arranged to conduct the short interview at a convenient time, by telephone or face-to-face. The short questionnaire included a mixture of closed and open questions about perceived needs for evidence to support parliamentary work, current access to evidence, and perceived needs for further training about types of evidence, its interpretation, and use. We conducted interviews mostly in Setswana with responses translated later into English. Interviewers entered responses to closed questions into an electronic spreadsheet and wrote out in full the responses to open questions.

Training sessions

The National AIDS Coordinating Agency (NACA) arranged and supported the training sessions. In November 2011, three of us (a professor of epidemiology who grew up in Botswana; a Canadian professor of biostatistics, originally from Lesotho; and a senior researcher leading a RCT of HIV prevention in Botswana, Namibia, and Swaziland) provided training for the representatives over one afternoon and the following morning. At the request of participants in 2011, the professor of epidemiology and the RCT researcher provided further training during two mornings in November 2012.

Table 1 summarises the training sessions, finalised in the light of responses to our survey of representatives. We emphasised the key role of counterfactual evidence and how to question biases in the generation of evidence. Participants learned about how policy relies on population parameters, like the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one adverse outcome, plus the relative irrelevance to policy of parameters of individual advantage. We also taught them about the odds ratio and its complement, ‘per cent protection’. Our teaching techniques included didactic lecture-style sessions, question and answer discussion sessions, and hands-on work in small groups. At the end of each training, participants completed a short anonymous evaluation questionnaire.

Results

Survey

None of the elected Representatives contacted in 2011 refused to be interviewed. Of those not interviewed, most were out of the country or not contactable; a few were unavailable for interview or could not attend the training because of pre-existing commitments. The interviewers conducted 17 interviews over the telephone and 10 face-to-face. They did not ask respondents about their age or educational level.

Nearly all respondents said they needed more evidence and more training about how to use evidence (Table 2). Asked about their sources of evidence, respondents mentioned evidence from committee papers, from the parliamentary research department, from lobbyists, from commissioned and non-commissioned advisers, from their constituencies, and from the press. For sources of evidence about HIV and AIDS, elected members considered the best to be: NACA, doctors and other health professionals, researchers, the Ministry of Health, the World Health Organisation, and civil society organisations.

The respondents cited difficulties they faced using evidence in their work. They mentioned problems with jargon, technical language, and statistical terms that led to problems with communicating the evidence and perhaps to bad decisions.

“The use of jargon makes it difficult to comprehend the evidence”.

“Some of it is too complicated to understand, with difficult wording and statistical data. This makes your work difficult in trying to use the evidence to address issues”.

“The technical terms used in the evidence are a challenge; communicating the evidence to the public then becomes a problem”.

“When the reports are not very easy to understand, especially the terminology, you can make a decision based on something you don’t understand”.

“User-friendly information is needed for policy audit and advocacy”.

A common complaint was lack of research staff for Parliament, inexperienced research officers, and an overall lack of relevant evidence.

“Research officers are inexperienced because of high turnover”.

“There is a lack of researchers dedicated to working with parliament”.

“The parliamentary research office is under-staffed”.

“There is a paucity of evidence; the inadequacy of evidence leads to wrong decisions and conclusions”.

Some respondents complained about difficulties with access to evidence, for example, via the Internet.

“Accessing information on the internet is a problem because our computers don’t work”.

“I don’t have adequate facilities, such as a laptop and internet connection, when I am outside the office. Basic training in ICT is limited, IT resources are limited”.

Some mentioned concerns about out-dated information.

“The evidence from government agencies is out-dated”.

“It affects the decision-making process because the evidence is not up to date”.

“The government thinks what they have is enough; they are not receptive to new evidence”.

Nearly all the respondents (25/27) believed that if they were better equipped to use evidence, this could help their work. They described the ways. Some explained how it would help their personal effectiveness.

“It would boost my confidence”.

“It would improve the quality of my presentations, for example to committees”.

“I would make arguments with enlightenment and knowledge”.

Many thought it would improve the speed and effectiveness of decision making.

“It will enhance the speed at which we can address issues because we spend a lot of time trying to comprehend the evidence and we fail to meet our target”.

“It will help in effective policy making”.

“It will put us in a better position to plan and make sound decisions”.

“It could assist us as members of Parliament to bring about positive change”.

Some mentioned specifically that it could help them communicate with their constituents.

“We’d have information to pass to our people [in our constituencies], with actual facts and knowledge”.

“It would help us with communicating to the communities that are illiterate or semi-illiterate in our constituencies”.

The final section of our questionnaire offered possible elements of training about evidence and use of evidence. For each element, we asked if they would like to learn more. Interviewers administered this section to 24 of the responding members of Parliament. Respondents were keen to learn about all the listed elements: types of evidence and their advantages and limitations (22); the language of scientific evidence (what the terms really mean) (22); presenting evidence so it is useful for planning (24); and questions parliamentarians can ask about evidence to determine its importance for them (23). Some suggested other elements: where and how to use research evidence; research methodologies; interpretation and use of evidence.

The trainings and their evaluation

There were some logistic challenges: late or undelivered official invitations in 2011 and a tight schedule in 2012. Nevertheless, a total of 36 elected Representatives attended one or both of the training sessions, including 7 ministers, the Deputy Speaker, the leader of the opposition, and the chair of the parliamentary committee on health and HIV and AIDS. The Director of HIV and AIDS Prevention and Care in the Ministry of Health also attended, as did the National Coordinator and other NACA personnel. The educational background of the participants varied from a school leaving certificate to completion of several advanced degrees.

Attendees participated actively, requesting clarifications, and related the information to their own work and to future consideration of the national AIDS policy. A few participants made political points in the discussions that followed presentations, but most of the content was conspicuously non-partisan. The groups considering the evidence examples in the final section of the first training explained the limitations of the evidence for planning correctly. The groups in the final section of the second training proposed feasible actions to enhance HIV prevention efforts. Participants appreciated the need to measure the impact on new HIV infections.

Everyone rated all sessions positively. On a scale of 1–5 (least to most positive), in 2011 the mean score for relevance of the content was 4.25, for level of the content 4.15, and for presentation 4.20. A majority (12/19) thought the length of the training was ‘about right’ and 7/19 thought it was too short. Participants recommended that the training be repeated for those members of Parliament, including ministers, who were unable to attend, as well as for other stakeholders including local governments, traditional leaders, non-government organisations, and church leaders. In 2012, the mean score for relevance was 4.5, for level 4.3, and for presentation 4.0. In the days following each training session, the Speaker reported positive feedback from the participants.

Discussion

Elected national representatives play a key role in setting policies, including health policies and, crucially, agree on budgets to support policies. The results from our small survey indicate that elected Representatives are well aware of the need to use evidence in their work, and feel hampered by lack of good quality and relevant evidence. They face difficulties in interpreting the evidence as it is presented to them from different quarters and in evaluating its importance for policy. The decisions they have to make may have profound consequences. Is the evidence sufficiently compelling that it should lead to a new set of policies without delay, and with adequate budget allocation, even if that means shifting funds away from existing programmes? Or is it highly suggestive but needs confirmation before making a major policy shift? Or is it interesting but not convincing, either because of some methodological flaws, or because it comes from a quite different setting?

Many other considerations come into play when making policy decisions. Studies have documented hindrances to evidence-informed health policymaking in both low- and high-income countries13, 23 and two systematic reviews reported many barriers to health policymakers using evidence: decision makers’ perceptions about research evidence; lack of contact between researchers and policymakers; research that was not timely or relevant; mutual mistrust; competing influences; and power and budget struggles.24, 25

If elected representatives had a better understanding of the evidence they need to support rational decision making, instead of being passive recipients, they could start to demand different kinds of evidence. For example, they might start to demand evidence on population as well as individual benefit; also on the NNT (to prevent one adverse outcome) and the unit costs of different programmes. They might push for systematic reviews and research syntheses, or at least for studies with acceptable counterfactual evidence. They could become active and informed parties in setting the research agenda.

This might seem far from reality and indeed it is in most places. However, that will not change if we, as researchers and teachers, decide that members of Parliament have neither the background nor the interest to learn about types of evidence needed for decision making, and about how to interrogate and use evidence. The Botswana experience confirms that members of Parliament were aware of their need for training and interested in learning. The two training sessions in Botswana covered more than half the elected Representatives and seven ministers, despite logistic problems with late and undelivered official invitations in 2011 and a tight schedule in 2012, when the training in the mornings took place while Parliament was sitting in the afternoons.

A survey among members of Parliament in several countries found that some felt they did not need training for elements of their role and many were opposed to compulsory training.9 The training programmes on offer did not include interpretation and use of evidence.9 In our survey, nearly all the respondents said they could benefit from training about use of evidence; we did not ask them if they thought such training should be compulsory, as there is no plan to make it so.

A recent survey of elected representatives in the Pacific region found that few perceived that training had a significant impact on their individual performances or on the performance of the Parliament. Respondents mentioned that the training programmes failed to take account of differing educational levels, were short, irregular, ad hoc or duplicative, and did not include a needs assessment.26

We have no evidence so far about the impact of the training we provided. Nearly all of those who attended the training considered it useful and recommended that it be offered to the remaining members of Parliament, including ministers, as well as to other groups in the country. Participation was lively and feedback (formal and informal) was positive. It will surely be difficult to attribute positive changes to the training, as this work was not designed as a trial (randomised or not), rather as a feasibility exercise. We intended it to contribute to understanding about what sort of training elected representatives want and can manage.

Why was the approach apparently successful and to what extent could it be used elsewhere? Seeking the views of the elected representatives ahead of time, reflecting back their views to them – and using this as a guide to the level and content of the training set a positive tone and increased the relevance of the training for the participants. This approach could be used in other places.

We took care to make the content accessible to the audience, most of whom had no background in quantitative sciences. We drew on our extensive experience teaching about the use of epidemiology for planning in many resource-poor settings. To increase relevance of the learning materials, we used examples from Botswana and the southern Africa region. Different examples could be used in other countries.

Local factors were important. Botswana has a small, functional, and relatively peaceful Parliament. Major conflicts within Parliament, not uncommon in the region, would make multi-party training such as this very difficult to implement. Finally, the minister for Presidential Affairs and Public Administration is influential and strongly committed to the idea of training members of Parliament to interpret and use evidence; his championing our project was a key element.

We see this as the beginning of a long road. Next steps include: providing training for advisers and technical officers, so they can provide ongoing support for members of Parliament and respond positively to demands for more and better evidence; setting up a monitoring scheme, tracking, for example, how often research evidence is cited in parliamentary debates; and creating a tool kit for similar exercises in other parliaments in the region. Despite the likely challenges, if a similar training approach could be applied in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, it could well contribute to formulating evidence-based policies to tackle the HIV epidemic and other pressing health problems.

Notes and References

Lavis, J.N., Robertson, D., Woodside, J.M., McLeod, C.B. and Abelson, J. (2003) How can research organisations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? The Millbank Quarterly 81 (2): 221–248.

Graham, I.D. et al (2006) Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 26 (1): 13–24.

Lavis, J.N., Posada, F.B., Haines, A. and Osei, E. (2004) Use of research to inform public policy making. Lancet 364 (9445): 1615–1621.

Lomas, J. (2007) The in-between world of knowledge brokering. British Medical Journal 334: 129–132.

Strand, P. and Bennett, S. (2007) Capacity for evidence filtration and amplification. In: A. Green, and S. Bennett (eds.) Sound choices-enhancing capacity for evidence-informed health policy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, pp. 91–106, http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/Alliance_BR.pdf.

Miles, A., Loughlin, M. and Polychronis, A. (2008) Evidence-based healthcare, clinical knowledge and the rise of personalised medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 14 (5): 621–649.

Sackett, D.L. and Rosenberg, W.M. (1995) The need for evidence-based medicine. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 88 (11): 620–624.

Hooker, R.C. (1997) The rise and rise of evidence-based medicine. Lancet 349 (9061): 1329–1330.

Davies, H.T.O. and Nutley, S.M. (1999) The rise and rise of evidence in health care. Public Money and Management 19 (1): 9–16.

Walshe, K. and Rundall, T.G. (2001) Evidence-based management: From theory to practice in health care. The Millbank Quarterly 79 (3): 429–457.

Lavis, J., Davies, H., Oxman, A., Denis, J.-L., Golden-Biddle, K. and Ferlie, E. (2005) Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 10 (suppl 1): 35–48.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. and Altman, D.G. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6 (7): e1000097.

Court, J. and Young, J. (2006) Bridging research and policy: Insights from 50 case studies. Evidence and Policy 2 (4): 439–462.

Deans, F. and Ademokun, A. (2013) Investigating capacity to use evidence: Time for a more objective view? INASP, http://www.inasp.info/uploads/filer_public/2013/07/04/investigating_capacity_to_use_evidence.pdf.

Report on international forum on evidence-informed health policy in low- and middle-income countries. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 27–31 August 2012, http://global.evipnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Addisreport2012.pdf.

World Health Organisation. (2013) Evidence-informed policy-making: SURE http://www.who.int/evidence/sure/en/, accessed 1 October 2013.

Geneau, R. et al (2009) Building capacity for HIV/AIDS prevention trials in Africa: Evidence from three projects supported by the Global Health Research Initiative. Retrovirology 6 (Supp 13): 94.

Elected Officials Education Program, Canada. (2013) http://www.eoep.ca, accessed 1 October 2013.

National Institute of Urban Affairs. (2006) Impact assessment of training of women elected representatives. New Delhi: National Institute of Urban Affairs, http://www.niua.org/projects/impact_assessment/impact-assessment.pdf, accessed 1 October 2013.

United Nations Development Programme. From reservation to participation: Capacity building of elected women representatives and functionaries of Panchayati Raj institutions, [http://www.undp.org/content/dam/india/docs/national_workshop_capacity_building_of_elected_women_representatives_and_functionaries_of_pris%20_report.pdf], accessed 1 October 2013.

Coghill, K. et al (2011) How should elected members learn parliamentary skills: An overview. Paper presented at international conference. Effective capacity building programs for parliamentarians, 19–20 October, Bern, Switzerland, http://www.ipu.org/splz-e/asgp11/coghill.pdf, accessed 1 October 2013.

UNAIDS. (2012) Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012, http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_with_annexes_en.pdf, accessed 1 October 2013.

Jewell, C.J. and Bero, L.A. (2008) “Developing good taste in evidence”: Facilitators of and hindrances to evidence-informed policy making in state government. The Millbank Quarterly 86 (2): 177–208.

Innvaer, S., Vist, G., Trommald, M. and Oxman, A. (2002) Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: A systematic review. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 7 (4): 239–244.

Orton, L., Lloyd-Williams, F., Taylor-Robinson, D., O’Flaherty, M. and Capewell, S. (2011) The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: Systematic review. PLoS One 6 (7): e21704.

Kinyondo, A. (2011) Return on training investment in parliaments: The need for change in the Pacific region. Paper presented at international conference. Effective capacity building programs for parliamentarians; 19–20 October, Bern, Switzerland, http://www.ipu.org/splz-e/asgp11/Kinyondo.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ditiro Laetsang, Leagajang Kgakole, Boikhutso Maswabi, and Neo Quinta Chose for interviewing the elected representatives. The authors also thank Richard Matlhare, National Coordinator of the National AIDS Coordinating Agency (NACA). NACA provided the training venue and arranged to invite participants. The authors were supported by the Global Health Research Initiative (GHRI), a research funding partnership of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada, and the International Development Research Centre. International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada made a grant for this work and the Government of Canada provided funds through Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The online version of this article is available Open Access

The authors explore how legislators use evidence in setting health policies in Botswana.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cockcroft, A., Masisi, M., Thabane, L. et al. Building capacities of elected national representatives to interpret and to use evidence for health-related policy decisions: A case study from Botswana. J Public Health Pol 35, 475–488 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2014.30

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2014.30