Abstract

The future of Detroit's automakers, even if they survive the current recession, looks grim. Cohort analysis of 24 years of US consumer household data suggests that the younger the head of the household, the more likely it is that the household automotive fleet includes foreign automakers’ vehicles. Furthermore, preferences for foreign vehicles increase slightly as heads of households age. A regression model confirms and extends this finding. The risk to Detroit automakers is that their US customer base is dying out.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In 1976, the domestic automakers’ share of the US market for cars and light trucks approached 85 per cent. (‘Domestic’ refers to companies headquartered in the United States.) By 2008, their share had decreased to about 47 per cent.1 What accounts for the domestics’ sharp decline? Will their share reverse direction and increase? Some basic research anchors answers to these questions on comparisons of domestic and foreign vehicles, emphasizing differences in matters such as quality and price (see Train and Winston2 for a sophisticated example). The industry and trade media, such as Automotive News, rely on applied research such as the J.D. Power studies.3 These studies also focus on quality, such as initial quality, of vehicles sold in America; Power, in addition, measures quality of vehicles after they have been in service for 3 years. In general, this line of research, both basic and applied, uses a micro-approach, attempting to measure the responses of individual customers through determining customers’ estimates of vehicle attributes such as quality, reliability and performance. This research has had considerable value. However, as differences among major manufacturers’ vehicles in some of these attributes have narrowed, a different mode of research offers promise in understanding changes in the domestics’ market share.

A more macro-approach can provide comprehension of the domestics’ likely futures in both the near term and the long term. In the near term, almost all automakers are experiencing steep sales declines. The domestics in the United States, however, are facing especially sharp fall-offs. This can be linked to product portfolios premised on high profits from expensive, low-mileage vehicles in the light truck category, vehicles the sales of which have been vanishing in the current environment. The domestic assemblers have also been badly damaged by the weakness of their customer-financing arms. The consequence is that both Chrysler and General Motors are veering close to bankruptcy. Nonetheless, some version of the domestic auto industry is likely to remain in the United States in the near term. Ford may well avoid bankruptcy completely, and even if both Chrysler and General Motors become bankrupt, it is possible that at least one of them, if not both, will emerge successfully from bankruptcy, though reduced in size.

The long term for these companies is more problematic. The companies are claiming that when the recession ends, their sales will rebound. Nevertheless, the argument advanced here is that even if all three companies survive the current recession, their prospects are clouded by shifts in the demographic base of their customers. This paper presents a macro-approach to analyze the changing composition of automotive buyers in the United States and link that to consumer preferences. This offers a useful viewpoint on factors underlying the domestic automakers’ shrinking fraction, and also permits forecasts of their market share. The Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers provided the data. The data were gathered over a span of 24 years. Synthetic cohorts of households are constructed to examine aging (or life cycle) effects and cohort effects. This allows a graphical display of differences in purchasing behavior among different automotive customers. Devising synthetic cohorts is a useful way to segment the population of automotive customers. A mathematical model is then constructed, to enable more exact estimates of those differences in behavior. The goal is to measure influences on the decision to obtain, through purchase or lease, domestic versus foreign light vehicles, and thus help to predict the domestics’ future share.

The authors make their homes in Michigan, the historic center of the US domestic auto manufacturers, and hence are concerned about the future of these firms. However, the research results do not offer a happy outlook in the United States for Chrysler, Ford and General Motors, the only significant domestic manufacturers remaining.

In the next section, the shifting market shares of domestic and foreign assemblers in the United States are placed in the context of the assumptions that the domestic manufacturers made about automotive consumers’ behavior. These assumptions are open to criticism. The subsequent section describes the methods used to understand the domestics’ changing share; these methods in effect test the domestics’ assumptions. This section includes a brief discussion of the use of cohort analysis. The penultimate section is of results. The paper closes with a final section of conclusions and discussion. In the following sections, the terms ‘automotive manufacturers,’ ‘manufacturers’ and ‘assemblers’ are used interchangeably. Note that references to consumers ‘owning’ a vehicle in their household fleets include leased as well as owned vehicles. Furthermore, this paper does not distinguish between new and used vehicles in the fleets, that is, sets of vehicles that households possess.

LIGHT VEHICLE MARKET SHARE: THE DOMESTIC VERSUS FOREIGN MANUFACTURERS

The marketing and the manufacturing strategies of General Motors were historically based on ‘a car for every pocket and purpose,’ a principle attributed to a long-serving GM executive, Alfred P. Sloan, Jr.4 The company believed that a buyer of modest means would initially purchase a vehicle from the company's Chevrolet Division, which offered the company's least expensive products. As the customer's financial situation improved over the years, the customer would be able to graduate to progressively more luxurious and expensive vehicles from, successively, GM's Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick and, finally, Cadillac Divisions. This would occur in part because of the assumption that a buyer established fairly early a general and stable preference for the products of one or another assembler. In time, Ford and Chrysler imitated this strategy. Ford, founded upon mass manufacture of inexpensive Ford products, later added the Mercury and Lincoln lines, so that its customers could also move up to more costly vehicles. Chrysler for a while offered five lines, ranging from the Plymouth, competing directly with Chevrolet and Ford, through the intermediate priced Dodge and DeSoto, to the high-end Chrysler and Imperial nameplates.

When foreign assemblers first began to sell small, mass-market cars, such as imported Toyotas and Volkswagen Beetles, in the United States, the domestic automakers tended to denigrate these vehicles as insignificant competitors. Initially, leaders at Chrysler, Ford and General Motors evinced no worry about the foreign vehicles posing a threat. Executives at the three major US assemblers believed that first-time buyers of these imported vehicles would, as their living standards rose, seek larger and better-equipped vehicles. Such buyers would necessarily switch to the vehicles of the domestics, such as a Pontiac or Oldsmobile, or a Mercury, or Dodge, and then stay with a domestic company, eventually moving up to a Cadillac, Lincoln or Chrysler, for example. Thirty to forty years later, some of that thinking still remains. For example, GM in recent years invested billions of dollars in rejuvenating its Cadillac Division, partly on that premise.

However, the logic of this is open to criticism. First, it is selective regarding the tenet of automotive marketing, that a buyer is likely to exhibit ‘brand loyalty.’ If the experience with the first vehicle of a manufacturer is good, then the buyer will tend to return to that same company for subsequent vehicles. Why wouldn't a satisfied first-time Toyota purchaser buy another Toyota when it was time to trade? Second, and related, is the manufacturers’ assumption that life cycle effects trump cohort effects. In other words, the domestic manufacturers thought that later cohorts of vehicle purchasers would act in the same way as earlier cohorts. If earlier cohorts tended to trade up from a Chevrolet or a Ford to a Pontiac or to a Mercury, then the belief was that later cohorts would dispose of their Volkswagen Beetles or little Datsuns to buy mid-priced domestic vehicles. But on the one hand, the foreign automakers undertook considerable efforts to build for this possibility, by creating more expensive models in addition to their less costly cars, just as Volkswagen offered the Passat above its various entry-level vehicles, and Nissan placed the Maxima above its Altima. Some of the foreign automakers also created their own luxury divisions. On the other hand, it is at least possible that later cohorts, as they aged, displayed a purchasing pattern that actually differed from that of earlier cohorts.

To test the domestic automakers’ assumption that young American buyers of foreign vehicles would revert to an American nameplate in subsequent purchases, a cohort analysis was developed, supplemented by a regression model. Underlying these was a conceptual model. The domestic automakers’ conceptual model involved a belief in the dominance of life cycle effects compared to cohort effects. The relative power of life cycle and cohort effects are explored in the three graphs presented. Patterns in the third graph, in particular, are used to help to construct a regression model; the model is presented following the graphs.

METHOD

An early explanation of cohort analysis and its use in marketing is Reynolds and Rentz.5 A recent and more general treatment of cohort analysis is that by Glenn.6 Examples of its application in marketing and related fields include Arsenault and Patrick, distinguishing among several cohorts (defined as various generations of Americans) in their value orientations; Beldona, discussing differences among cohorts in online travel search behavior; Berri, discussing variation in car ownership over time using cohort techniques; Chen, Wong and Lee, using cohort methods to analyze life insurance purchases; You and O’Leary, distinguishing age and cohort effects in travel activities of older Japanese; and Rentz and Reynolds, employing cohort techniques to forecast product consumption (of coffee).7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Advantages, in principle, of cohort analysis include the potential to deal with several kinds of influences on the unit of analysis

-

1

Cohort effects, that is, influences of experiences common to a set of consumers who have shared an event, such as birth year or interval, for example.

-

2

Age effects, that is, influences of aging or stage of the life cycle on a set of consumers.

-

3

Period effects, that is, influences at a particular time of aspects of the economy or of social life on all consumers.

A limitation of cohort analysis is in disentangling all three kinds of influences simultaneously. The technical term for this is the identification problem; it flows from the fact that there is a dependency among the operations used to calculate values for the three kinds of influences. Often, however, it is possible to combine additional data or reasonable assumptions with the evidence from cohort analyses to make useful estimates of the three kinds of influences. An early collection of technical essays on cohort analysis is Mason and Fienberg; a later, briefer explication is Mason and Wolfinger.13, 14 A very recent, though demanding, treatment of the technique with a proposed solution to the identification problem is Yang, et al.15

A drawback of cohort analysis in marketing applications is that it is not often coupled with a set of data that extends over a substantial number of years. For this paper, however, data that ranged over 24 years were available. At the same time, this paper follows Glenn (p. 1).6

Cohort analysis … is a general strategy for examining data rather than a specific statistical technique …

In particular, cohort analysis here is used to develop ideas about relationships in data; this is followed by a regression model in order to test some of the ideas.

The Surveys of Consumers involve telephone interviews on a monthly basis, with a sample of households in the United States. The Surveys are conducted under the aegis of the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research, and are sponsored by the University of Michigan and by Reuters. Each month, data are gathered from about six hundred households. The data are used to construct, among other things, a number of indices, including the Index of Consumer Sentiment. For this paper, however, the focus is on those data collected by the survey that pertain to the vehicles that members of the household own and/or lease. Data are available from the Surveys for a considerable number of years; data from 1980 through 2003 are analyzed for this paper.16

The data include the total number of vehicles in the household, whether each vehicle is a car or instead a light truck (defined as a pickup truck, minivan or sport utility vehicle), and whether each vehicle was made by a domestic or a foreign manufacturer. The data also include additional information on each household, such as real income and age of the head of the household. To these data was added information for the years 1980–2003 on the real price of unleaded regular gasoline and a new car price index. Also added was information on the market share held by foreign manufacturers during the years (ages 21–25) when the head of the household was young (and presumably forming a brand identification).

The project involved constructing a panel of synthetic cohorts. (Actual panels of cohorts could not be assembled, because the membership in some of the samples of households changes from month to month.) With this limitation in mind, these details describe the research strategy

-

1

The cohorts were defined by the birth year of the head of the household. Each cohort included a 5-year interval of birth years. As it turned out, there were 12 cohorts, and the heads were born in 1921–1925, 1926–1930, 1931–1935, 1936–1940, 1941–1945, 1946–1950, 1951–1955, 1956–1960, 1961–1965, 1966–1970, 1971–1975 and 1976–1980, respectively. Because these are panels of synthetic cohorts, the households at various times along a single line for a single cohort in the graphs are not necessarily all the same. Nonetheless, the households are similar in that, for the line for a single cohort, all the heads of households were born in the same interval. Also omitted are data from households where the heads of the households had become older than 65 years of age, or had not yet attained age 21.

-

2

For each cohort, as many data points were plotted as was possible for 24 years of the survey, 1980 through 2003, with each data point representing an entire year. For each cohort, for each year in the series, data were pooled from the 12-monthly surveys of that year. For some cohorts, this meant fewer data points than for others. For example, for the cohort with heads born in 1921–1925, the series started in 1980, when the head of the household would have turned 55–59, but ended no later than 1990, when the youngest head in the interval turned 65.

-

3

In the graphs, age of head of household is displayed along the x-axis. The y-axis shows other variables of interest.

In additional analysis, described below, data from the cohorts were used in a regression.

RESULTS

Graphs of the cohorts

In the first graph the average number of vehicles per household in each cohort against age of the head of the household is plotted. Thus, it is possible to see how a cohort changes in relation to how many vehicles its households own, on average, as the cohort ages, and to compare cohorts with respect to this change (Figure 1).

The graph demonstrates that the number of vehicles per household follows a roughly similar life cycle pattern for all the cohorts, with ownership at moderate levels for households with a young head, rising to a peak for households the head of which is in his or her mid-40s, and then declining again to the lowest levels in the graph as the heads of households reach their mid-60s. Note that at the extremes of the age distribution displayed here, some of the cohorts are missing data. Nonetheless, for the data available, there is not a strong cohort effect. Size of household fleet, instead, seems to reflect a life cycle or aging effect, with the size of the fleet reaching a maximum when the number of drivers in the household is most likely to reach a maximum.

In the second graph, cars as a share or per cent of all vehicles (cars plus light trucks, defined as pickup trucks, minivans and sport utility vehicles) owned by the household, averaged for all households in a cohort, are plotted against average age of the head of the household, for the cohorts (Figure 2).

This demonstrates that over time for all the cohorts, cars became a decreasing proportion of all vehicles (including both cars and light trucks) owned by households. From an initial point, at which the cars constituted as much as 80 per cent of these households’ vehicle fleets, the cohorts moved to a situation in which cars made up, for some cohorts, as little as 50 per cent or less. Thus, there was a sizable effect, but it is interpreted as a period effect, the increasing availability and popularity of light trucks, rather than an aging effect. However, the pattern varied from one cohort to the next, indicating a small cohort effect as well. In particular, for the later cohorts, the decline was a little steeper. Thus, the graph indicates that cohorts born later were more likely to shift over time to still more light trucks in their household fleets. Furthermore, for the very latest cohorts, the starting point was a little lower, with cars making up closer to 70 per cent, rather than 80 per cent, of vehicles in the household, on average, and by the end of the series of data points, for these cohorts, passenger cars made up less than 50 per cent of their households’ vehicles. The pattern is somewhat different for the older, or earlier, cohorts. For the earliest three cohorts, car ownership at the end of the series, in 2003, still ranges from almost 70 per cent to almost 80 per cent, that is, the decline is slight.

The domestic assemblers, first to market with pickup trucks, minivans and sport utilities, initially benefited from the trend to light trucks, but then found some of the foreign assemblers building competitive vehicles in this segment. The trend to light trucks may have initially masked and delayed the trend to vehicles built by the foreign manufacturers, discussed next. The domestic manufacturers today, as fuel costs have risen, are hampered by excess capacity, particularly for low-mileage vehicles such as large SUVs and full-size pickup trucks, as the demand for these products has fallen very steeply.

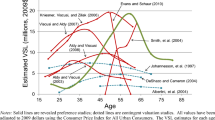

The third graph tracks, for each cohort, the fraction of households the vehicles of which are exclusively domestic against age of household head (Figure 3). (For simplicity, the households are divided into only two categories: those that possess solely domestic vehicles, and those that own either a mix of domestic and foreign vehicles, or only foreign vehicles.)

It is evident that earlier cohorts (right side of the graph), compared to the later cohorts (left side of the graph), are more likely to have a household vehicle fleet that is initially domestic-only in the data set. The first cohort, for example, began 1980 with over 80 per cent of its households owning only domestic vehicles. Later cohorts, by contrast, were somewhat less likely to have a household vehicle fleet that was initially domestic-only in the data set. The first cohort consisted, in 1980, of heads of households who were in their 50s, and who had made their earlier vehicle purchases in an era in which vehicles with foreign nameplates were uncommon in the United States. By contrast, the latest cohort, consisting of heads born in 1976–1980, would have entered the data set no earlier than 1997. By that time, when these heads of households would have been making their first vehicle purchases, foreign nameplates had considerable market share in vehicle sales. The cohort effect here is pronounced, and appears to be that people's automotive purchasing patterns are influenced by the range of automotive options available at the time they begin to own or lease vehicles. For third graph, the later cohorts are more open to foreign vehicle purchases.

The other pattern, much smaller, is what occurs to each cohort's household fleets over time. Generally speaking, there was a reduction for each cohort in the fraction of households that have only domestic vehicles in their possession. Thus, even the earliest cohort experienced a fall in its proportion of domestic vehicle-only households, from a little over 80 per cent to somewhat over 70 per cent. The same pattern continued in nearly all of the other cohorts. In particular, some of the later cohorts (younger heads of households) were not returning to the fold of exclusively domestic vehicles in their fleets, but in fact over time experienced a reduction in the per cent of domestic vehicle-only households. The reductions were quite small, and did not differ greatly in amount from one cohort to another. Nevertheless, the key point for the analysis is that there was not a pattern of turning back to domestic vehicles as cohorts aged, contradicting the assumption of the domestic automakers.

Regression model

To capture more fully the factors underlying the shift from domestic vehicles, a multivariate regression model was developed. The dependent variable, fraction of households with only domestic vehicles, or domestic loyalty, is the fraction of households for a particular cohort and a particular year that owns or leases only domestic vehicles. In the analysis, this fraction was first subjected to a natural logarithmic transformation. The cases, 223 in all, consist of observations for each cohort (12-monthly surveys pooled into 1-yearly total) for each year a cohort was in the surveys of consumers.

The independent variables were as follows:

Import Share (21–25) is, for each cohort, the average share of the new market held by foreign assemblers at the time when that cohort's heads of households were 21–25 years of age. This is designed to measure the market at the time of the cohort members’ first entry, in order to capture any persistent effect on domestic versus foreign vehicle ownership.

Number of Vehicles is the average number of vehicles per household in each cohort's households’ fleets, for each year the cohort was in the surveys of consumers. It is included in the equation as a control variable, because size of the fleet affects the composition of the fleet. For each cohort, for each year, the average number of vehicles in all the household fleets was determined.

New Car Price Index is a new car price index for each year from 1980 through 2003. (Note that a price index for new light trucks and a price index for all new vehicles were not available.)

Real Price of Unleaded Regular is the real price of unleaded regular gasoline for each year from 1980 through 2003.

Real Income per Adult ′03 is the real income of the household, per adult in the household, averaged for the cohort (in thousands of 2003 dollars) for the year.

Imputed Income is a measure of the average adult income for the year for households in a cohort that did not respond to the question about income. It was derived through a statistical routine in the course of processing the data. The fraction of a cohort in which income is imputed is positively correlated with the cohort's average income. If the imputed income variable were not included in the regression, the coefficient for real income per adult $2003 would be biased toward zero. It is included here only to correct for that bias, and thus serves as a control variable.

The hypotheses were as follows:

-

1

The higher the import share when a cohort's heads of households were young (21–25), the lower will be the percentage of domestic-only households in that cohort.

-

2

The more vehicles, on average, in a cohort's household fleets, the lower will be the percentage of the cohort's domestic-only households.

-

3

As new car prices increase, the percentage of domestic-only households in cohorts will decrease.

-

4

The real price of unleaded regular gasoline will be negatively related to the percentage of a cohort's domestic-only households. This hypothesis is founded on the fact that in the United States, domestic vehicles on average have lower fuel economy than foreign vehicles on average.

-

5

Average real income per adult in the household, averaged for all households in the cohort, will be negatively related to the cohort's percentage of domestic-only households. Various factors underlie this hypothesis, including the options available to lower-income Americans: in the set of used vehicles in the United States, domestic vehicles are still the large majority, and, in addition, the weaker residual values of domestic versus foreign vehicles in the United States make used domestic vehicles, on average, more affordable for such customers.

The results of the analysis can be seen in Table 1.

The results demonstrate the following:

First, the import share of the market for each cohort when the cohort was young (heads of household aged 21–25), and therefore was first entering the vehicle market, is related to the cohort's household fleets. In particular, the higher the import share at the time when the cohort was young, the lower is the percentage of domestic-only fleets for that cohort. The result is significant at better than the 0.001 level. It appears that the particular range of automotive offerings extant when a person first begins to own vehicles has an influence, both short-term and long-term, on the person's choices.

Second, as the average household fleet increases in size, the likelihood that it will remain all-domestic decreases. (This is partly because of the fact that statistically, an all-domestic large fleet is less likely to occur than an all-domestic small fleet; as mentioned above, this variable was included as a type of control.)

Third, as the new car price index increases, loyalty to domestic vehicles decreases, in that domestic-only fleets decrease. This result is significant at better than the 0.001 level. This is especially ominous for the domestic manufacturers: they have been making their profits on the higher margins provided by light truck sales. Overall sales of light trucks, of course, are plummeting in current conditions. What this indicates is that, in an era when cars, for their better gas mileage, are being preferred to light trucks, customers are even willing to pay premium prices for cars, while abandoning light trucks, which often carry high profit margins. This shift or trend benefits foreign manufacturers because they can more readily increase sales of all their car brands (through adding imports to their vehicles assembled in the factories they have in the United States), and because they include in their car product lines in the United States a range of high-mileage vehicles, including some costly ones.

Fourth, as the real price of unleaded gasoline increases, domestic-only fleets decrease. This is significant at the 0.02 level. The interpretation is that customers shift to more fuel-efficient vehicles; on average, fleets of domestic automakers have demonstrated lower miles per gallon than have those of the foreign automakers.

Fifth, the higher the average real income per adult in the household, averaged for the cohort, the lower the percentage of domestic-only fleets. This is significant at the 0.03 level. This is threatening to the domestic manufacturers, as it means that their market is concentrating in the lower-income levels of the US population. It was important to include a measure of household income, in part because the buying patterns of higher-income households are often a harbinger of future purchasing patterns of households from other income levels. Thus, the long-term danger to the domestic manufacturers is that lower-income households, over time, may seek to emulate higher-income households in preferring vehicles of foreign manufacturers. (Admittedly, at times the lower-income households may have to purchase used vehicles of foreign manufacturers, because such households may not be able to afford new ones.)

There is a significant relationship between the imputed income variable and the dependent variable, but no hypothesis is offered, as it serves as a control variable, described above.

In total, the variables included in the model explain about 68 per cent of the variance in the dependent variable domestic loyalty.

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

For the domestic automakers, the results presented here, in the graphs and in the regression model, may be unsettling. The results indicate the following:

-

1

Most of the cohorts, regardless of date of birth, tend over the years to experience, if anything, a reduction in the proportion of households that own exclusively domestic vehicles. This directly contradicts the hope of some domestic executives in the past that, over the course of their purchasing lifetimes, Americans who had bought or leased foreign vehicles would replace them with domestic ones. The data do not support this hope.

-

2

Furthermore, extrapolating from the data, additional patterns must be disquieting for the domestic assemblers. The earlier cohorts, with their older heads of household, tended to have higher proportions of domestic-only households, but as they age, as the first graph shows, they possess fewer vehicles in their household fleets. Further, these earlier cohorts will be the first to pass from the scene. Their places will be taken by later cohorts. These later cohorts, throughout the years that it was possible to track them, had lower proportions of domestic-only fleets. Some of these households consist of families whose first automotive purchase was from a foreign assembler, and whose subsequent one or two purchases were also from foreign manufacturers. It will be very hard for GM, Ford or Chrysler to lure these households back to a domestic nameplate. ‘Conquest sales’ of this type will be difficult to achieve.

-

3

As the model indicates, additional trends look bleak for the domestic manufacturers. Higher-income heads of households are more likely to favor foreign assemblers’ vehicles. In addition, rising prices of new cars actually are associated with declining loyalty to domestic vehicles. Initially, of course, the growth of foreign assemblers’ market share was based on small, inexpensive vehicles. However, the creation of barriers to the numbers of their vehicles (the voluntary restraint agreements in the 1980s, for example) made it profitable for the foreign manufacturers to import to the US vehicles with higher-transaction prices, and in general to develop for sale in the United States, whether imported into the United States or built in transplants there, more of such costly vehicles. What the data indicate is that the market in the United States for more expensive vehicles is increasingly a market for foreign nameplates. Finally, when prices for unleaded regular gasoline rise, loyalty to domestic vehicles declines.

Alternate strategies of the domestic assemblers to cope with this situation have not borne much fruit. At times, the domestics have made partial or full purchases of up-scale foreign assemblers, so that they could offer foreign nameplates to households that were moving up to or wanted to maintain luxury or near-luxury foreign vehicles in their household fleets. But GM's purchase of Saab has not resulted in enhanced sales of that make in the United States. Ford's and Chrysler's past ventures with Italian automakers to offer foreign sport vehicles in the United States (Ford's Pantera, the Maserati TC by Chrysler) came to naught. Ford has sold much of its Premier Automotive Group, having let go of Jaguar, which over the years has been a costly loss for the company, and Land Rover, which did better. Ford also disposed of Aston Martin. Ford retains the car division of Volvo, but largely because it has not found a buyer.

The domestics have also attempted to purchase, partly or entirely, foreign assemblers with a presence in compact or sub-compact cars, and to import these after badging them with domestic identification. Thus, Ford has brought in sub-compacts at various times, and Chevrolet imports the sub-compact Aveo from GM's Daewoo operation in Korea. These have had respectable sales in the market place, but are not a major profit source in the United States. Further, it is not clear what a household buys after a successful experience for several years with such a vehicle. Does the household move up, after an Aveo, to a GM domestically assembled vehicle? Or does it decide that, having owned a foreign built sub-compact vehicle with satisfaction, it will move up to a Honda Civic or Accord or a Toyota Corolla or Camry?

Additional possibilities encompass the following. First, the domestic manufacturers’ assumption that consumers would, over their lifetimes, buy successively more costly vehicles is becoming open to question. What if some consumers change in the future? What if, in particular, later cohorts of consumers decide not to spend more on each subsequent vehicle they purchase, at least during periods of economic recession? Perhaps, compared to earlier cohorts, they choose to allocate a greater fraction of their disposable income to other goods and services. The increasing quality, leading to increasing longevity, of vehicles enables this. For example, the median age of cars in use in the United States increased from 4.9 years, in 1970, to 8.9 years, in 2004.17 Thus, a young household, getting its first new car, perhaps buys a domestic vehicle, such as a new Ford compact, like a Focus. Five years later, the family trades in the Focus and buys a used Ford mid-size, such as a 3-year-old Fusion. And the household made that decision only after deciding not to trade in the Focus on … another, but new, Focus.

The suspicion that this is happening is based on shifts in overall ownership patterns. In 1980, for example, almost 42 per cent of American households held (through purchase or lease) only new vehicles in their household fleets. However, by 2003 that fraction had declined to about 28 per cent. By contrast, in 1980, nearly 35 per cent of American households owned or leased only used vehicles for their household fleets, but by 2003 that had increased to about 44 per cent.18 When the information is disaggregated by age of head of household, it is evident that the trend away from acquiring only new vehicles for the household fleet holds for all age categories of heads of household, though older heads are in general more likely than younger ones to maintain fleets of vehicles acquired when new.18 Similarly, this trend holds for all four household income quartiles.18

Second, the general method displayed here depends on data collected over a series of years. The hope is that the results encourage readers to consider both exploiting such data sources and advocating the creation of similar sources. A true panel study, with the same respondents queried repeatedly over a period of years, is ideal, but hard to accomplish without serious attrition of respondents. However, these results show that research conducted over a period of years, even with non-identical respondents, can be valuable, and allows analysis that is not possible with a survey conducted at only a single time point.

Third, the approach in this paper lends itself to analyzing other consumer purchases such as housing. In the United States, owning a detached, single-family house has long been a goal of many Americans, but the data that are available suggest that this may be changing for younger Americans. Public policy in the United States has helped to support homeownership in general. The fraction of all households owning domiciles peaked near 70 per cent a few years ago, but has since declined somewhat. Based on that policy and that percentage, the building industry in the United States (far more decentralized than the automotive industry) has emphasized single-family homes. Nonetheless, younger heads of households today are growing up in an economy of increasing inequality. Furthermore, the career trajectories of younger people display a greater frequency of job changes, frequently tied to changes in location. Thus, their own situation, combined with much more careful lending by financial institutions in the wake of the credit problems in the American economy, may push these heads of households away from detached single-family houses, and to alternatives such as renting for a number of years. What they rent may well be apartments or possibly condominiums that are leased by owners or developers. If these younger heads of households return to the market to purchase a domicile, their experiences may prepare them for ownership of a condominium, or a unit in a cooperative housing development, or possibly a duplex. Intriguing data are available through the US government.19 Long-term data on home-ownership among various age categories suggest that while rates of homeownership among older Americans increased in recent decades, such rates for younger Americans were relatively flat. The implication for the residential construction industry is that there will be continuing demand for rental units, perhaps accompanied by diminished demand for owner-occupied single-family housing.

Finally, there are additional implications for the domestic automotive manufacturers. Part of the cause of their decline in market share in their US market lies in an underestimate, dating to the 1980s, of the potential of their foreign competitors to create larger, more luxurious and more profitable models than those competitors first introduced. But part of the domestics’ problem flows from being less nimble than their foreign competitors in responding to changes in the marketplace. The domestic manufacturers have lagged behind their foreign counterparts in reconfiguring assembly plants to include flexible lines capable of switching from one type of vehicle to another on short notice. This was quite noticeable in the first half of 2008. Economic weakness in the United States, involving falling equity values, tightening of consumer credit, and sharply declining residential real estate values, combined with rising prices for vehicle fuels, in general led to sharply decreased new vehicle sales. However, sales of small cars surged.20 For example, Honda's total sales through June for 2008 in the United States were actually ahead of the company's sales for the first half of 2007, in large part because of soaring deliveries of cars such as its Civic small car. Honda's success is partly because of its being positioned favorably in fuel-efficient vehicles, and partly because of its ability to ramp up availability of Civics. The harsh lesson for industrial firms is that future success will increasingly depend on the capacity for flexibility in manufacturing. The increasingly dour news from the Detroit automakers raises the question as to how many of the three will last long enough to develop such capacity for flexibility. Even if all three survive the current recession, they are very dependent on a customer base of aging buyers who will be decreasing the size of their household fleets; this raises the specter that one or more of the Detroit three may fade away before regaining the ability to be competitive.

References

Automotive News. (2009) US car and light-truck sales by make – 12 months 2008. 12 January, p. 29.

Train, K. E. and Winston, C. (2004) Vehicle choice behavior and the declining market share of US automakers. International Economic Review 48: 1469–1496.

Power, J. D. and Associates. (2008) 2008 Initial Quality Study (IQS). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Sloan Jr, A. P. ([1963]1990) My Years with General Motors. New York: Doubleday.

Reynolds, F. D. and Rentz, J. O. (1981) Cohort analysis: An aid to strategic marketing. Journal of Marketing 45: 62–70.

Glenn, N. D. (2005) Cohort Analysis, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Arsenault, P. M. and Patrick, M. L. (2008) Are the shoes appropriate to wear?: A study of cohort values. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 16 (2): 99–107.

Beldona, S. (2005) Cohort analysis of online travel information search behavior: 1995–2000. Journal of Travel Research 44: 135–142.

Berri, A. (2002) Longitudinal analysis of car ownership in different countries. In: M. Patriksson and M. Labbe (eds.) Transportation Planning. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 229–245.

Chen, R., Wong, K. A. and Lee, H. C. (2001) Age, period, and cohort effects on life insurance purchases in the United States. The Journal of Risk and Insurance 68: 303–327.

You, X. and O'Leary, J. T. (2000) Age and cohort effects: An examination of older Japanese travelers. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 9 (1/2): 21–42.

Rentz, J. O. and Reynolds, F. D. (1991) Forecasting the effects of an aging population on product consumption: An age-period-cohort framework. Journal of Marketing Research 28 (3): 355–360.

Mason, W. M. and Fienberg, S. E. (eds.) (1985) Cohort Analysis in Social Research: Beyond the Identification Problem. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Mason, W. M. and Wolfinger, N. H. (2001) Cohort Analysis. Los Angeles: University of California at Los Angeles. California Center for Population Research – Online Working Paper Series.

Yang, Y., Schulhofer-Wohl, S., Wenjiang, J. F. and Land, K. C. (2008) The intrinsic estimator for age-period-cohort analysis: What it is and how to use it. American Journal of Sociology 113 (6): 1697–1736.

Curtin, R. (1980–2003) Surveys of Consumers. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Davis, S. C. and Diegel, S. W. (2006) Transportation Energy Data Book, 25th edn. Oak Ridge, TN: Center for Transportation Analysis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, pp. 3–15.

Curtin, R. (2004) New and used vehicle purchases among US households, 1980–2003. Unpublished Research Report, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, pp. 1–2, 5–6.

US Census Bureau. (2007) Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2007, 127th edn. Washington DC: Department of Commerce.

Snyder, J. (2008) Japanese can add small cars faster than Detroit 3. Automotive News. 9 June, p. 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McManus, W., Senter, R., Curtin, R. et al. The demographic threat to Detroit's automakers. J Target Meas Anal Mark 17, 81–92 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2009.8

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2009.8